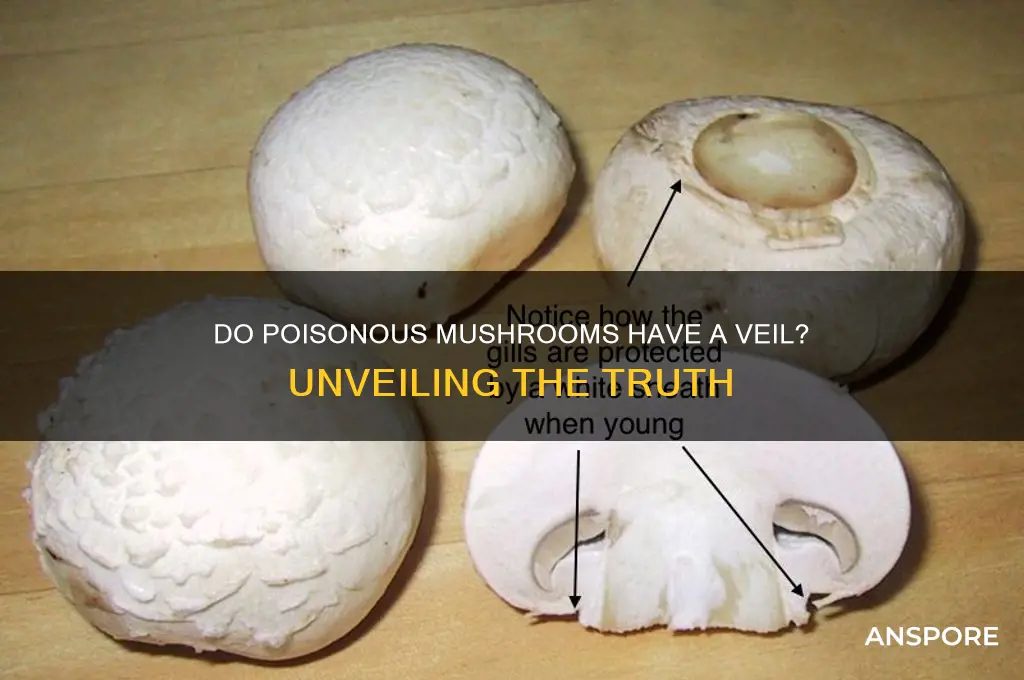

Poisonous mushrooms, like many of their non-toxic counterparts, often exhibit a veil—a delicate, membrane-like structure that connects the cap to the stem during the mushroom's early developmental stages. This veil serves as a protective layer for the developing gills or pores beneath the cap. As the mushroom matures, the veil typically ruptures, leaving behind remnants such as a ring on the stem or patches on the cap. While the presence of a veil is not exclusive to poisonous mushrooms, it is a common feature in many species, both toxic and edible. Identifying whether a mushroom with a veil is poisonous requires careful examination of other characteristics, such as color, spore print, and habitat, as the veil alone is not a reliable indicator of toxicity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Veil Presence | Some poisonous mushrooms have a veil (partial veil or universal veil), but not all. Veil presence alone is not a reliable indicator of toxicity. |

| Examples with Veil | Amanita phalloides (Death Cap), Amanita ocreata (Destroying Angel), Galerina marginata (Deadly Galerina) |

| Examples without Veil | Conocybe filaris (Fool's Conocybe), Cortinarius rubellus (Deadly Webcap), Lepiota brunneoincarnata (Fatal Lepiota) |

| Reliability as Toxicity Indicator | Low; many edible mushrooms also have veils, and some poisonous mushrooms lack veils. |

| Key Toxicity Factors | Presence of toxins (e.g., amatoxins, orellanine), not veil characteristics. |

| Safe Identification Method | Consult expert guides, use spore prints, and avoid consumption unless 100% certain. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Veil Presence in Toxic Fungi

The presence of a veil in mushrooms is a distinctive feature often associated with their early developmental stages, but its correlation with toxicity is a nuanced topic. Veils, which are membranous structures that protect the gills or pores of young mushrooms, are not exclusive to toxic species. However, certain poisonous mushrooms, such as the deadly Amanita species, often retain remnants of their veils as they mature, appearing as a cup-like volva at the base or patches on the cap. This makes the veil a potential, though not definitive, indicator of toxicity. Foraging enthusiasts should note that while a veil’s presence warrants caution, its absence does not guarantee safety.

Analyzing specific examples highlights the veil’s role in identifying toxic fungi. The *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap), one of the most poisonous mushrooms, typically displays a prominent volva and partial veil remnants. Similarly, *Amanita ocreata* (Destroying Angel) retains a cup-like base and patchy veil fragments. These features, combined with other characteristics like white gills and a smooth cap, create a profile that experienced foragers learn to avoid. However, not all toxic mushrooms have veils; *Galerina marginata* (Deadly Galerina), for instance, lacks a volva but is equally lethal. This underscores the importance of considering multiple identifiers, not just the veil, when assessing mushroom toxicity.

For those venturing into mushroom foraging, understanding the veil’s significance is a critical step in avoiding toxic species. A practical tip is to examine the base of the mushroom for volva remnants and the cap for veil patches. If either is present, especially in conjunction with white gills or a bulbous base, it’s best to err on the side of caution. Additionally, carrying a field guide or using a reliable identification app can provide real-time assistance. Remember, ingestion of even a small amount of toxic mushrooms like *Amanita phalloides*—as little as 50 grams—can be fatal, making accurate identification paramount.

Comparatively, edible mushrooms with veils, such as certain *Volvariella* species, often have distinct features that differentiate them from toxic counterparts. For example, the *Volvariella volvacea* (Paddy Straw Mushroom) has a volva but lacks the white gills and bulbous base typical of toxic Amanitas. This comparison illustrates how the veil, while a red flag, must be evaluated within the broader context of the mushroom’s morphology. Foraging courses or local mycological clubs can provide hands-on training to refine identification skills, ensuring safer harvesting practices.

In conclusion, the veil’s presence in toxic fungi is a valuable but not foolproof indicator of danger. Its utility lies in its association with highly poisonous species like Amanitas, but reliance on a single feature can lead to misidentification. A comprehensive approach, combining veil examination with other morphological traits and expert guidance, is essential for safe foraging. As the adage goes, “There are old foragers and bold foragers, but no old, bold foragers”—a reminder that caution and knowledge are the best tools in the field.

Are Shaggy Ink Cap Mushrooms Poisonous? Facts and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Identifying Poisonous Mushroom Veils

The presence of a veil in mushrooms is a fascinating yet potentially deceptive feature. While many edible mushrooms, like the beloved Amanita caesarea, boast a distinct veil, this characteristic is not exclusive to safe species. In fact, some of the most toxic mushrooms, such as the deadly Amanita phalloides, also possess a veil, making it a crucial but tricky identifier. This duality underscores the importance of understanding the nuances of mushroom veils when foraging.

To identify poisonous mushroom veils, start by examining the veil’s structure and remnants. Poisonous species often leave a fragile, membranous veil that may break into fine, scattered fragments on the cap or stem. For instance, the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) typically retains veil remnants as a skirt-like ring on the upper stem and patches on the cap. In contrast, edible veils are often thicker, more resilient, and leave cleaner, more defined remnants. Always use a magnifying lens to inspect these details, as subtle differences can be lifesaving.

A comparative approach can further aid identification. For example, the veil of the edible Paddy Straw Mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) forms a distinct, sack-like volva at the base, which is thicker and more persistent than the fragile volva of the poisonous Amanita bisporigera. Additionally, note the color and texture of the veil. Poisonous veils are often white or pale, blending seamlessly with the mushroom’s cap and stem, while edible veils may exhibit contrasting colors or textures. However, never rely on color alone, as variations can occur within species.

Practical tips for safe foraging include documenting your findings with detailed photographs and notes. If unsure, consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide. Avoid consuming any mushroom with a veil unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Remember, even experienced foragers occasionally mistake poisonous veils for edible ones, so caution is paramount. By focusing on the veil’s characteristics and employing a systematic approach, you can minimize risks and enhance your mushroom identification skills.

Are Giant Yard Mushrooms Poisonous? Identifying Your Front Yard Fungi

You may want to see also

Veil Role in Mushroom Toxicity

The presence of a veil in mushrooms is a fascinating yet often misunderstood feature, especially when discussing toxicity. Veils, which are membranous structures that protect the developing gills or pores of a mushroom, are not inherently indicators of toxicity. Both edible and poisonous mushrooms can have veils, making this characteristic a poor sole determinant of a mushroom’s safety. For instance, the Amanita genus, notorious for its deadly species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), often features a prominent universal veil that forms a volva at the base of the stem. However, edible species like the Paddy Straw Mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*) also possess a veil. The key takeaway is that the veil itself is neutral—it’s the species and its specific toxins that dictate danger.

Analyzing the veil’s role in toxicity requires understanding its function during a mushroom’s development. The veil protects the spore-bearing structures (gills or pores) from damage and contamination as the mushroom matures. In some toxic species, the veil’s remnants, such as patches on the cap or a volva at the base, can serve as identifying features. For foragers, recognizing these remnants is crucial. For example, the presence of a volva or a ring (partial veil remnants) in combination with other features like white gills and a bulbous base should raise red flags, as these traits are common in toxic Amanitas. However, relying solely on the veil is risky; always cross-reference with other characteristics like spore color, gill attachment, and habitat.

From a practical standpoint, here’s a step-by-step approach to assessing mushroom toxicity in relation to veils: 1) Observe the veil remnants—look for a volva, ring, or patches on the cap. 2) Note the mushroom’s overall appearance, including color, shape, and habitat. 3) Cross-reference these features with reliable field guides or apps. 4) If unsure, avoid consumption entirely. A critical caution: even touching certain toxic mushrooms, like those containing amatoxins, can transfer toxins to food or mucous membranes, so wear gloves when handling unknown species. The goal is not to memorize every veil type but to recognize patterns that, when combined with other traits, signal potential danger.

Comparatively, the veil’s role in toxicity highlights a broader principle in mycology: no single feature guarantees a mushroom’s safety or danger. For instance, while the veil in Amanitas is a red flag, the absence of a veil in species like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita ocreata*) doesn’t make it safe. Similarly, edible veiled mushrooms like the Maidenhead Mushroom (*Coprinus comatus*) lack toxins but can cause issues if consumed with alcohol. This underscores the importance of holistic identification. Dosage matters too—even mildly toxic mushrooms can cause severe reactions in children or pets due to their smaller body mass. Always err on the side of caution and consult experts when in doubt.

In conclusion, the veil’s role in mushroom toxicity is nuanced and context-dependent. It serves as a protective structure during development and can leave behind identifying features in mature mushrooms. However, its presence or absence is not a reliable indicator of toxicity on its own. Foragers must adopt a multi-faceted approach, combining veil observations with other characteristics and expert guidance. Practical tips include wearing gloves, avoiding consumption of unknown species, and prioritizing education over guesswork. By understanding the veil’s limited role, enthusiasts can better navigate the complex world of mushrooms while minimizing risk.

Are Brown Garden Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common Veiled Poisonous Species

Veils in mushrooms, often seen as delicate membranes under the cap, can be a deceptive feature. While many edible species have veils, several highly toxic mushrooms also possess this characteristic, making identification crucial. Among the most notorious veiled poisonous species is the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*). This mushroom’s veil remnants form a distinctive cup-like structure at the base, known as a volva, and patches on the cap. Its toxin, amatoxin, causes severe liver and kidney damage, with symptoms appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion. Even a small bite can be fatal, making it essential to avoid any mushroom with a volva or persistent veil remnants.

Another veiled culprit is the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera* and *A. ocreata*), often mistaken for edible button mushrooms due to its white, veiled appearance. Its veil leaves a ring on the stem and patches on the cap, similar to some harmless species. However, it contains the same deadly amatoxins as the Death Cap. A single Destroying Angel contains enough toxin to kill an adult, and its symptoms—delayed gastrointestinal distress followed by organ failure—are often misdiagnosed, leading to fatal outcomes. Always avoid white, gilled mushrooms with veils unless positively identified by an expert.

For foragers in the Pacific Northwest, the Western Poison Conecap (*Conocybe filaris*) is a veiled species to watch for. Its fragile veil leaves faint traces on the cap and a barely visible ring on the stem. This mushroom contains the toxin conocybesin, which causes severe gastrointestinal symptoms within hours of ingestion. While rarely fatal, its small size and nondescript appearance make it easy to overlook, often growing in lawns and gardens. Teach children and pets to avoid touching or tasting any small, veiled mushrooms, as even handling can transfer spores.

Lastly, the Fool’s Mushroom (*Amanita verna*) is a veiled species that mimics the edible meadow mushroom. Its white cap, veil remnants, and bulbous base are classic warning signs, yet its toxin—again, amatoxin—has claimed lives due to misidentification. Unlike some poisonous species, it lacks a strong odor or immediate taste deterrent, making it particularly dangerous. If you encounter a white, veiled mushroom with a bulbous base, assume it’s toxic and leave it undisturbed. When in doubt, remember: no veil feature guarantees edibility, and expert verification is non-negotiable.

Do All Poisonous Mushrooms Have Veils? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Veil vs. Edible Mushroom Comparison

The presence of a veil in mushrooms is a critical feature for foragers to note, as it can be a red flag for toxicity. Many poisonous mushrooms, such as the deadly Amanita species, have a universal veil that leaves behind distinctive remnants: a cup-like volva at the base and patches on the cap. These features are absent in most edible varieties, making the veil a key differentiator. However, not all veiled mushrooms are toxic, and not all edible mushrooms lack veils, so this trait must be considered alongside other characteristics.

To safely identify edible mushrooms, focus on species with well-documented, veil-free structures. For instance, the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) and the chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) lack a universal veil and are widely consumed. When foraging, avoid any mushroom with a volva or veil remnants unless you are absolutely certain of its identity. Beginners should stick to easily identifiable, veil-free species and consult field guides or experts to avoid confusion.

A comparative analysis reveals that veiled mushrooms often belong to genera associated with toxicity, such as *Amanita* and *Cortinarius*. These genera contain some of the most poisonous mushrooms in the world, including the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*). In contrast, edible genera like *Boletus* and *Lactarius* typically lack a universal veil. This pattern underscores the importance of veil presence as a preliminary screening tool, though it should never be the sole criterion for identification.

For practical foraging, follow these steps: First, examine the mushroom base for a volva or bulbous structure, which indicates a veil was present. Second, check the cap for patches or warts, another veil remnant. Third, cross-reference these observations with a reliable guide. If in doubt, discard the mushroom—consuming even a small amount of a toxic veiled species can be fatal. For example, as little as 50 grams of *Amanita phalloides* can cause severe poisoning in adults. Prioritize caution over curiosity to ensure a safe foraging experience.

Are Truffles Poisonous? Debunking Myths About These Gourmet Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all poisonous mushrooms have a veil. The presence or absence of a veil is not a reliable indicator of toxicity.

Yes, some poisonous mushrooms do have a veil. The veil is a structural feature, not a marker of edibility or toxicity.

No, the absence of a veil does not guarantee a mushroom is safe. Many poisonous mushrooms lack a veil, and proper identification is crucial.

A veil is a protective layer that covers the gills or cap during development. Its presence or absence is unrelated to toxicity and should not be used to determine edibility.