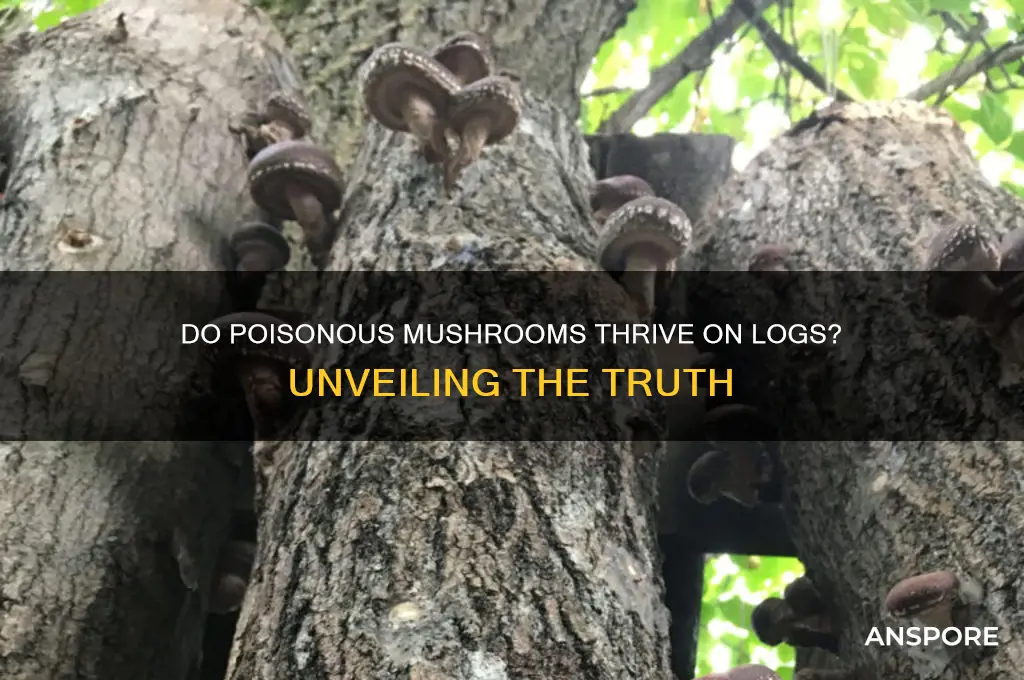

Poisonous mushrooms can indeed grow on logs, as many fungal species thrive in woody environments where they decompose organic matter. Logs, especially those that are decaying, provide an ideal substrate rich in nutrients and moisture, which supports the growth of various mushrooms, including toxic varieties. Common poisonous species such as the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) are known to grow in wooded areas, often near logs or stumps. However, not all mushrooms growing on logs are dangerous, and identifying them accurately requires knowledge of specific characteristics, such as coloration, gill structure, and spore type. It is crucial to exercise caution and avoid consuming wild mushrooms without expert guidance, as misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even fatality.

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Preferred Substrates: Do poisonist mushrooms favor logs over other substrates like soil or wood chips

- Log Decay Stage: Are specific decay stages of logs more suitable for poisonist mushroom growth

- Species Specificity: Do certain poisonist mushroom species exclusively grow on logs

- Environmental Factors: How do humidity, temperature, and light affect log-grown poisonist mushrooms

- Toxicity Levels: Does growing on logs influence the toxicity of poisonist mushrooms

Preferred Substrates: Do poisonist mushrooms favor logs over other substrates like soil or wood chips?

Poisonous mushrooms, often referred to as toxic fungi, exhibit diverse preferences when it comes to their growth substrates. While some species thrive on logs, others may favor soil, wood chips, or even decaying organic matter. The question of whether poisonous mushrooms specifically favor logs over other substrates is complex and depends on the particular species in question. For instance, certain toxic fungi, like the infamous *Amanita* species, are often associated with mycorrhizal relationships and are commonly found in soil near the roots of trees. These mushrooms do not typically grow directly on logs but rather in the surrounding soil, benefiting from their symbiotic relationship with tree roots.

Logs, being a form of woody debris, provide a unique environment that some poisonous mushrooms find suitable. Species such as the *Galerina* genus, which contains several toxic members, are known to grow on decaying wood, including logs and stumps. These mushrooms are saprotrophic, meaning they obtain nutrients by breaking down dead organic material. The structure of logs, with their rich cellulose and lignin content, offers an ideal substrate for such fungi to colonize and fruit. However, it is essential to note that not all poisonous mushrooms that grow on wood are limited to logs; some may also be found on smaller wood chips or even buried wood in the soil.

Soil, as a substrate, is incredibly diverse and can support a wide variety of fungal species, including many poisonous ones. Mushrooms like the *Cortinarius* genus, some of which are highly toxic, often grow in soil and form mycorrhizal associations with trees. These fungi play a crucial role in forest ecosystems by helping trees absorb nutrients from the soil. Wood chips, on the other hand, can provide a similar environment to logs but with a higher surface area, allowing for more rapid colonization by certain fungal species. Some poisonous mushrooms, such as those in the *Hypholoma* genus, are known to grow on wood chips, especially in mulch or compost piles.

The preference for logs over other substrates is not a universal trait among poisonous mushrooms. Each species has evolved to thrive in specific ecological niches, and their substrate preferences are a result of these adaptations. Factors such as nutrient availability, moisture content, pH levels, and competition from other organisms all influence where a particular mushroom species will grow. For example, logs might offer a more stable and nutrient-rich environment for certain saprotrophic fungi, while mycorrhizal species may prefer the dynamic conditions of soil.

In conclusion, while some poisonous mushrooms do grow on logs and find them favorable, it is inaccurate to generalize that all toxic fungi prefer logs over other substrates. The diversity of mushroom species and their ecological roles means that substrate preferences vary widely. Understanding these preferences is essential for both mycological research and practical applications, such as mushroom foraging, where correctly identifying the substrate can be a critical factor in distinguishing between edible and poisonous species.

Exploring Pennsylvania's Forests: Where and How Mushrooms Thrive in the Wild

You may want to see also

Log Decay Stage: Are specific decay stages of logs more suitable for poisonist mushroom growth?

The relationship between log decay stages and the growth of poisonous mushrooms is a fascinating aspect of mycology. Logs undergo a natural decomposition process, progressing through various decay stages, each characterized by distinct physical and chemical changes. These stages can significantly influence the types of fungi that colonize the wood, including poisonous species. Understanding which decay stages are most conducive to the growth of toxic mushrooms is crucial for both foragers and researchers.

In the early decay stage, logs begin to lose their structural integrity as sapwood and heartwood start to break down. This stage is typically dominated by pioneer fungi that decompose cellulose and hemicellulose. While some mushrooms may appear during this phase, poisonous species are less common because the environment is still relatively nutrient-rich and competitive. The wood retains enough strength to support only certain types of fungal growth, often favoring non-toxic varieties.

As logs transition into the advanced decay stage, the wood becomes softer, and lignin decomposition accelerates. This stage is more favorable for a diverse range of fungi, including poisonous mushrooms. Species like *Amanita* and *Galerina*, known for their toxicity, often thrive in this environment. The increased availability of nutrients and the reduced competition from pioneer fungi create ideal conditions for these toxic species to establish and fruit. Foragers must exercise caution during this stage, as the presence of poisonous mushrooms becomes more likely.

The final decay stage, characterized by crumbly, soil-like wood remnants, is less suitable for most mushroom growth, including poisonous varieties. At this point, the log has been largely reduced to humus, and the nutrients have been depleted. While some fungi may still persist, the conditions are no longer optimal for the fruiting bodies of toxic mushrooms. This stage is more conducive to saprotrophic organisms that break down the last remnants of organic matter.

In summary, specific decay stages of logs do influence the suitability for poisonous mushroom growth. The advanced decay stage is particularly favorable for toxic species, as it provides the right balance of nutrients and structural support. Foragers should be especially vigilant during this phase, while researchers can focus on this stage to study the ecology of poisonous fungi. Understanding these dynamics not only enhances safety but also deepens our appreciation of the intricate relationships between fungi and their substrates.

Exploring North Georgia's Forests: Can Black Truffles Thrive There?

You may want to see also

Species Specificity: Do certain poisonist mushroom species exclusively grow on logs?

The question of whether certain poisonous mushroom species exclusively grow on logs is an intriguing aspect of mycology, particularly for foragers and enthusiasts who need to accurately identify potentially harmful fungi. While many mushrooms do favor wood-based substrates, the relationship between poisonous species and logs is not as straightforward as a simple yes or no. Some poisonous mushrooms are indeed saprotrophic, meaning they decompose dead wood, and thus are commonly found growing on logs, stumps, or fallen branches. However, exclusivity to logs is rare, as most species can adapt to various environments depending on availability of nutrients and other growth conditions.

One notable example of a poisonous mushroom often associated with logs is the Galerina marginata, commonly known as the "deadly galerina." This species is frequently found on decaying wood, particularly coniferous logs, and is responsible for several cases of poisoning due to its resemblance to edible mushrooms like honey fungi. Despite its preference for wood, *Galerina marginata* is not exclusive to logs and can also grow on soil enriched with woody debris. Similarly, Clitocybe dealbata, or the ivory funnel, is another poisonous species that often appears on wood chips or mulch but is not strictly confined to logs. These examples highlight that while logs are a common habitat, they are not the sole environment for these toxic fungi.

In contrast, some poisonous mushrooms are less likely to be found on logs. For instance, the infamous Amanita phalloides (death cap) and Amanita ocreata (destroying angel) are mycorrhizal species, forming symbiotic relationships with tree roots rather than decomposing wood. These deadly mushrooms typically grow in soil near trees, particularly oaks and other hardwoods, and are rarely, if ever, found on logs. This distinction underscores the importance of understanding the ecological preferences of specific mushroom species to avoid misidentification.

Species specificity regarding logs also depends on geographical and environmental factors. In temperate forests with abundant fallen timber, poisonous wood-decomposing mushrooms like Hypholoma fasciculare (sulfur tuft) are more prevalent on logs. However, in regions with less woody debris, these species may adapt to alternative substrates. Additionally, cultivation practices, such as using wood chips in gardening, can artificially increase the presence of log-associated mushrooms in non-natural settings.

In conclusion, while certain poisonous mushroom species, such as *Galerina marginata* and *Hypholoma fasciculare*, have a strong affinity for logs, exclusivity to this substrate is uncommon. Most toxic fungi exhibit flexibility in their habitat preferences, growing on logs when available but also thriving in soil, mulch, or other organic matter. Foragers must therefore rely on a combination of habitat clues, morphological features, and ecological knowledge to accurately identify poisonous mushrooms, rather than assuming their presence based solely on their association with logs.

Exploring Morel Mushrooms: Do They Thrive in Costa Rica's Climate?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors: How do humidity, temperature, and light affect log-grown poisonist mushrooms?

Environmental Factors: How Do Humidity, Temperature, and Light Affect Log-Grown Poisonous Mushrooms?

Humidity plays a critical role in the growth of poisonous mushrooms on logs. These fungi thrive in environments with high moisture levels, as their mycelium requires consistent water to decompose wood and form fruiting bodies. Logs with a moisture content of 40–60% are ideal for species like the deadly Galerina marginata or Amanita phalloides. Insufficient humidity can halt growth, while excessive moisture (e.g., waterlogged logs) may lead to rot or competition from other organisms. Growers or foragers must ensure logs remain damp but not saturated, often achieved through misting or placement in naturally humid environments like shaded forests.

Temperature is another decisive factor influencing the development of log-grown poisonous mushrooms. Most species prefer cool to moderate temperatures, typically between 50°F and 70°F (10°C–21°C). Extreme heat can desiccate the mycelium, while freezing temperatures may kill it. For example, Amanita species often fruit in autumn when temperatures drop, signaling optimal conditions. Fluctuations outside this range can delay fruiting or prevent it entirely. Logs should be situated in areas with stable temperatures, such as forest floors, where natural insulation moderates extremes.

Light exposure indirectly affects poisonous mushrooms growing on logs, primarily by influencing the microclimate and moisture retention. While these fungi do not require light for photosynthesis, indirect or diffused light helps maintain humidity by reducing rapid evaporation. Direct sunlight, however, can dry out logs and raise temperatures, creating unfavorable conditions. Shaded environments, such as under dense canopies, are ideal as they mimic the mushrooms' natural habitat. Light also affects the orientation of fruiting bodies, though this is less critical for their survival compared to humidity and temperature.

The interplay of these environmental factors determines the success of poisonous mushrooms on logs. For instance, high humidity combined with suitable temperatures accelerates wood decomposition, providing nutrients for mycelial growth. However, without adequate shade, even optimal humidity and temperature may fail to support fruiting. Understanding these relationships is essential for both mycologists studying toxic species and foragers avoiding accidental poisoning. Logs in environments that naturally balance these factors—cool, shaded, and consistently moist—are most likely to host dangerous species like the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera) or the Funeral Bell (Galerina marginata).

In practical terms, managing these factors requires careful observation and intervention. For controlled cultivation, logs can be inoculated with spores and kept in humidity-controlled chambers with regulated temperature and light. In the wild, poisonous mushrooms often appear after rain in cooler seasons, highlighting the importance of moisture and temperature synergy. Light, though less directly impactful, ensures the ecosystem remains stable. Whether in a forest or a lab, mastering these environmental variables is key to understanding—and avoiding—the growth of log-dwelling toxic fungi.

Cultivating Psilocybin Mushrooms: A Comprehensive Guide to Growing Psy Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Toxicity Levels: Does growing on logs influence the toxicity of poisonist mushrooms?

The question of whether growing on logs influences the toxicity of poisonous mushrooms is a nuanced one, requiring an examination of both mycological biology and environmental factors. Poisonous mushrooms, such as those from the *Amanita* genus (e.g., the Death Cap, *Amanita phalloides*), are known for their potent toxins, but their toxicity is primarily determined by their species and genetic makeup rather than their substrate. However, the environment in which they grow, including the type of substrate like logs, can potentially influence the concentration of toxins they produce. Logs, being rich in lignin and cellulose, provide a unique nutrient profile that may affect the mushroom’s metabolic processes, including toxin synthesis.

Research suggests that the toxicity of poisonous mushrooms is inherently species-specific, meaning that a mushroom’s ability to produce toxins is genetically encoded. For example, *Amanita* species produce amatoxins, which are deadly regardless of whether they grow on soil, logs, or other organic matter. However, the availability of certain nutrients in logs, such as heavy metals or specific organic compounds, could theoretically modulate toxin production. Studies have shown that environmental stressors, like nutrient availability or competition with other fungi, can sometimes increase toxin levels in mushrooms as a defense mechanism. While logs themselves are not inherently linked to higher toxicity, the specific conditions they provide might play a minor role in toxin concentration.

It is important to note that the substrate alone is not a reliable indicator of a mushroom’s toxicity. Poisonous mushrooms can grow on a variety of substrates, including logs, soil, and even grass. The key factor remains the species of the mushroom. For instance, the toxic *Galerina marginata* can grow on wood, while the edible oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) also grows on logs. Thus, identifying mushrooms based on their substrate is highly unreliable and dangerous. Instead, toxicity is determined by the mushroom’s internal chemistry, which is consistent across different growth environments.

While logs provide a unique habitat for mushrooms, there is no conclusive evidence that growing on logs universally increases the toxicity of poisonous species. The primary determinant of toxicity remains the mushroom’s genetic predisposition to produce specific toxins. However, environmental factors associated with log-based growth, such as nutrient availability or microbial interactions, could theoretically influence toxin levels in some cases. For foragers, the focus should always be on accurate species identification rather than assumptions about substrate-related toxicity.

In conclusion, the toxicity of poisonous mushrooms is not significantly influenced by their growth on logs. Toxicity is a species-specific trait, and while environmental factors like nutrient availability might play a minor role in toxin concentration, the substrate itself is not a determining factor. For safety, it is crucial to avoid consuming wild mushrooms without expert identification, regardless of where they grow. Understanding the biology and ecology of these fungi is essential for both scientific research and public safety.

Identifying Edible Garden Mushrooms: Safe or Toxic in Your Backyard?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, some poisonous mushrooms, such as the deadly Galerina marginata, can grow on decaying wood, including logs.

No, not all mushrooms growing on logs are safe. Some, like the poisonous species in the genus *Galerina* or *Hypholoma*, thrive on wood and can be toxic or deadly if ingested.

Identifying poisonous mushrooms requires knowledge of specific traits, such as spore color, gill structure, and cap features. Always consult a field guide or expert, as many toxic species resemble edible ones.

Yes, some edible mushrooms, like oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus* spp.) and certain species of *Lentinula* (shiitake), grow on logs. However, proper identification is crucial to avoid toxic look-alikes.