Sac fungi, also known as Ascomycota, are a diverse group of fungi characterized by their unique method of spore production. One of their defining features is the presence of small, sac-like structures called asci (singular: ascus), which are typically found within fruiting bodies such as mushrooms or flask-shaped structures. Inside each ascus, sexual spores called ascospores are produced through a process known as meiosis. These spores are then released into the environment, where they can germinate and grow into new fungal individuals. This reproductive strategy is a key adaptation that has contributed to the success and widespread distribution of sac fungi in various ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Production | Yes, sac fungi (Ascomycota) produce spores inside a small sac-like structure called an ascus. |

| Ascus Structure | A microscopic, sac-like structure typically containing 8 spores (though numbers may vary). |

| Spore Type | Ascospores, which are often haploid and serve as the primary means of dispersal and reproduction. |

| Ascus Function | Protects and nurtures spores until they are ready for release. |

| Release Mechanism | Spores are ejected from the ascus through a pore or by the rupture of the ascus wall. |

| Examples of Sac Fungi | Yeasts, morels, truffles, and many plant pathogens like powdery mildew and apple scab. |

| Ecological Role | Decomposers, mutualistic symbionts (e.g., lichens), and pathogens in various ecosystems. |

| Classification | Belong to the phylum Ascomycota, one of the largest groups of fungi. |

| Economic Importance | Used in food production (e.g., baker's yeast), medicine (e.g., penicillin), and biotechnology. |

| Reproduction | Primarily sexual, with ascospores formed during the sexual phase of their life cycle. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ascus Structure: Small sac-like structures called asci house and protect developing spores in sac fungi

- Ascospore Formation: Spores, known as ascospores, develop inside asci through sexual reproduction processes

- Ascocarp Role: Fruiting bodies (ascocarps) enclose asci, facilitating spore release and dispersal

- Sexual Reproduction: Fusion of hyphae leads to ascus formation, ensuring genetic diversity in spores

- Spore Release: Asci rupture or open to release ascospores for wind or water dispersal

Ascus Structure: Small sac-like structures called asci house and protect developing spores in sac fungi

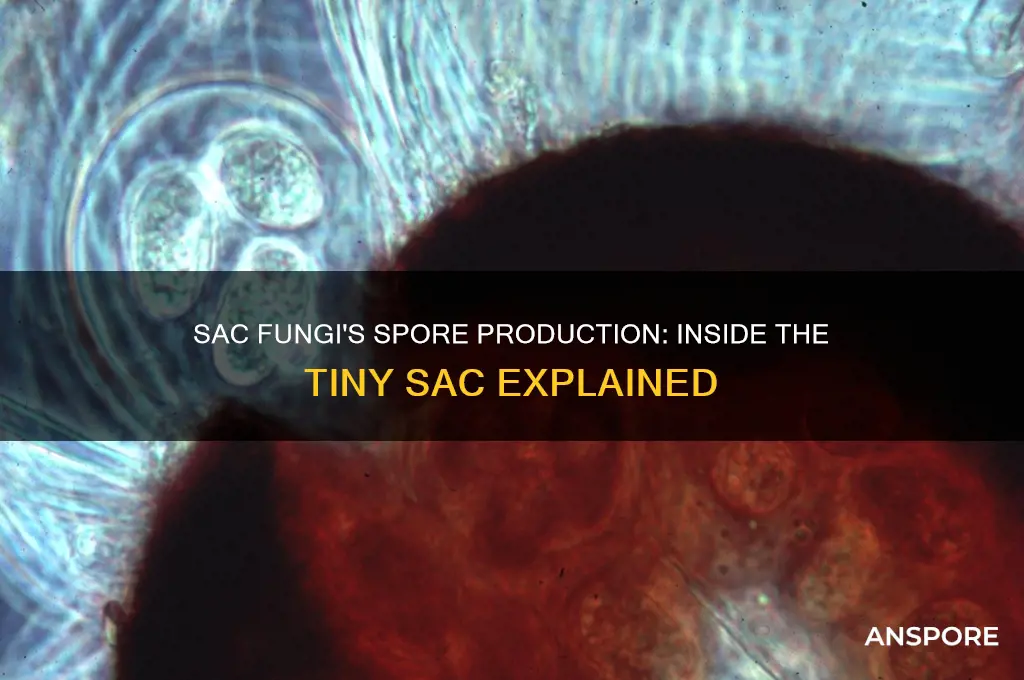

Sac fungi, or Ascomycota, are a diverse group of organisms characterized by their unique reproductive structures. At the heart of their life cycle lies the ascus, a small, sac-like structure that serves as the cradle for developing spores. These asci are not merely containers; they are dynamic microenvironments where genetic diversity is fostered through processes like karyogamy and meiosis. Each ascus typically houses eight spores, known as ascospores, which are the result of sexual reproduction. This design ensures that the spores are protected during their development, increasing their chances of survival and dispersal.

Consider the ascus as a biological incubator, meticulously engineered to shield its contents from environmental stressors. Its robust yet flexible cell wall provides a barrier against desiccation, predation, and mechanical damage. For instance, in the model organism *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast), the ascus wall composition includes chitin and glucan, which confer structural integrity. This protective mechanism is particularly crucial during the early stages of spore development, when the genetic material is most vulnerable to mutations or damage. Without the ascus, the spores would be exposed to harsh conditions, significantly reducing their viability.

From a practical standpoint, understanding ascus structure is essential for industries that rely on sac fungi. In biotechnology, for example, the controlled production of ascospores within asci is leveraged for genetic studies and strain improvement. Researchers manipulate environmental factors like temperature (optimal range: 20–25°C) and humidity (70–80%) to induce ascus formation in species such as *Neurospora crassa*, a common lab fungus. Similarly, in agriculture, knowledge of ascus biology aids in managing fungal pathogens, as disrupting ascus development can limit spore dispersal and disease spread.

Comparatively, the ascus structure sets sac fungi apart from other fungal groups, such as Basidiomycota, which produce spores on club-like structures called basidia. The enclosed nature of the ascus allows for more controlled spore maturation, a feature that likely contributed to the evolutionary success of Ascomycota, which now represent over 75% of all described fungal species. This distinction highlights the ascus as a key innovation, enabling sac fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from soil to symbiotic relationships with plants.

In conclusion, the ascus is not just a small sac but a sophisticated biological compartment that safeguards the future of sac fungi. Its structure and function exemplify nature’s ingenuity in ensuring reproductive success. Whether in scientific research, industrial applications, or ecological contexts, the ascus remains a focal point for understanding and harnessing the potential of these remarkable organisms. By studying its intricacies, we gain insights into fungal biology and its broader implications for biotechnology and beyond.

Do Liverworts Have Spores? Unveiling Their Unique Reproductive Secrets

You may want to see also

Ascospore Formation: Spores, known as ascospores, develop inside asci through sexual reproduction processes

Sac fungi, or Ascomycota, are a diverse group of organisms that play a crucial role in ecosystems, from decomposing organic matter to forming symbiotic relationships with plants. One of their most distinctive features is the production of ascospores, which develop inside specialized structures called asci. This process, known as ascospore formation, is a fascinating example of sexual reproduction in fungi, combining genetic diversity with structural precision.

The Process of Ascospore Formation

Ascospore formation begins with the fusion of haploid cells, a process called plasmogamy, followed by the merging of their nuclei (karyogamy) during sexual reproduction. This genetic recombination occurs within the ascus, a sac-like structure that acts as a protective incubator for the developing spores. Inside the ascus, the diploid nucleus undergoes meiosis, producing four haploid nuclei, which then divide mitotically to form eight nuclei. Each nucleus is enveloped by cytoplasm to create an ascospore. This intricate process ensures genetic diversity, a key advantage for fungi adapting to changing environments.

Structural Precision in Ascospore Development

The ascus itself is a marvel of fungal engineering. Typically club-shaped, it is composed of a layer of cells that provide structural support and protection. The number of ascospores per ascus varies among species, but it is always a multiple of four due to the meiotic process. For example, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) produces four ascospores per ascus, while *Aspergillus* species may produce eight. This consistency highlights the precision of fungal reproductive mechanisms, ensuring efficient spore dispersal and colonization.

Practical Implications and Applications

Understanding ascospore formation has practical applications in agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. For instance, *Trichoderma*, a genus of sac fungi, is used as a biocontrol agent to combat plant pathogens. Its ascospores are produced in perithecia, a type of ascus-containing structure, and are released to colonize and protect crops. In medicine, *Penicillium* species, which produce ascospores, are the source of penicillin, a groundbreaking antibiotic. By studying ascospore formation, scientists can optimize spore production for industrial and therapeutic purposes.

Comparative Advantage of Ascospores

Compared to spores produced by other fungal groups, ascospores offer unique advantages. Their development within the ascus provides protection during maturation, ensuring higher viability upon release. Additionally, the sexual nature of their formation results in genetic recombination, which enhances adaptability and survival in diverse environments. This contrasts with spores produced asexually, such as conidia, which lack genetic diversity. For example, while *Aspergillus* produces both ascospores and conidia, the ascospores are more resilient and better equipped to colonize new habitats.

In summary, ascospore formation is a sophisticated reproductive strategy that underscores the complexity and adaptability of sac fungi. By developing spores inside asci, these fungi ensure genetic diversity, structural integrity, and ecological success. Whether in natural ecosystems or industrial applications, the study of ascospores continues to reveal insights into fungal biology and its practical implications.

Befriending Epic Creatures in Spore: A Guide to Unlikely Alliances

You may want to see also

Ascocarp Role: Fruiting bodies (ascocarps) enclose asci, facilitating spore release and dispersal

Sac fungi, or Ascomycota, are a diverse group of organisms characterized by their unique method of spore production. At the heart of this process lies the ascocarp, a specialized structure that plays a pivotal role in the life cycle of these fungi. Ascocarps, often referred to as fruiting bodies, are not merely passive containers; they are dynamic systems designed to optimize spore release and dispersal. Within these structures, asci—microscopic, sac-like cells—develop and mature, each containing eight spores arranged in a precise pattern. This encapsulation ensures protection during development and provides a mechanism for efficient ejection when conditions are favorable.

Consider the cup fungus (*Peziza*) as a practical example. Its ascocarp forms a cup-like structure, often visible on decaying wood or soil. Inside this cup, asci line the fertile layer, poised to discharge spores when triggered by environmental cues such as humidity or temperature changes. For gardeners or mycologists observing this process, noting the timing and conditions of spore release can provide insights into fungal behavior and aid in managing ecosystems where these fungi thrive. For instance, maintaining a humid environment around decaying organic matter can encourage ascocarp formation and subsequent spore dispersal, promoting fungal diversity.

From an analytical perspective, the ascocarp’s design is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation. Its structure varies widely across species, from the delicate, cup-shaped apothecia of *Pezizales* to the perithecia of *Neurospora*, which resemble tiny flasks embedded in substrate. Each form is tailored to the fungus’s ecological niche, optimizing spore dispersal strategies. For example, apothecia are often elevated to catch air currents, while perithecia rely on passive release or insect vectors. Understanding these variations can inform conservation efforts, as disrupting ascocarp formation—through habitat destruction or pollution—can severely impact fungal populations and the ecosystems they support.

To observe ascocarp function firsthand, a simple experiment can be conducted. Collect a sample of decaying wood or leaf litter where sac fungi are likely present. Place it in a sealed container with a damp paper towel to maintain humidity, and monitor daily for the emergence of fruiting bodies. Once ascocarps form, gently expose them to a light air current or temperature change to simulate natural triggers. Using a magnifying glass or microscope, observe the asci’s response, noting the forceful ejection of spores. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the ascocarp’s role but also highlights the precision of fungal reproductive mechanisms.

In conclusion, the ascocarp is far more than a protective casing; it is a sophisticated dispersal system that ensures the survival and propagation of sac fungi. By enclosing asci within a structured environment, it maximizes the efficiency of spore release, adapting to diverse ecological conditions. Whether you’re a researcher, hobbyist, or simply curious about the natural world, understanding the ascocarp’s role offers a deeper appreciation for the complexity and ingenuity of fungal life cycles. Practical observations and experiments can further illuminate this process, making it a tangible and fascinating subject of study.

Growing Morels from Spores: Unlocking the Mystery of Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sexual Reproduction: Fusion of hyphae leads to ascus formation, ensuring genetic diversity in spores

Sac fungi, or Ascomycota, are masters of sexual reproduction, a process that hinges on the fusion of hyphae—the thread-like structures that form their bodies. This union is not merely a physical merger but a sophisticated dance of genetic exchange. When compatible hyphae meet, they intertwine, forming a specialized structure called an ascogonium, which initiates the reproductive cycle. This fusion is the first step in creating an ascus, a microscopic, sac-like structure that will house the next generation of spores.

The formation of the ascus is a marvel of biological engineering. Within this sac, a series of nuclear divisions occur, culminating in the production of eight haploid spores, known as ascospores. These spores are genetically diverse, a direct result of the recombination of DNA during the fusion of hyphae. This diversity is crucial for the survival of the species, enabling populations to adapt to changing environments and resist diseases. For instance, in agricultural settings, this genetic variability helps fungi like *Trichoderma* species combat soil-borne pathogens effectively.

To visualize this process, imagine a tiny, egg-shaped vessel—the ascus—acting as a cradle for genetic innovation. Each ascospore, encased within, carries a unique genetic blueprint, a testament to the power of sexual reproduction. This mechanism contrasts sharply with asexual reproduction, where spores are clones of the parent, limiting adaptability. In nature, this diversity is evident in the vast array of Ascomycota species, from the edible morel mushrooms to the destructive Dutch elm disease pathogen.

Practical applications of this reproductive strategy abound. For example, in biotechnology, genetically diverse ascospores are harnessed for producing enzymes and antibiotics. Researchers cultivate specific Ascomycota species under controlled conditions, inducing hyphal fusion to maximize ascus formation. A key tip for optimizing this process is maintaining a temperature range of 20–25°C and a humidity level above 80%, as these conditions mimic the fungi’s natural habitat and encourage reproductive success.

In conclusion, the fusion of hyphae and subsequent ascus formation in sac fungi is a cornerstone of their reproductive strategy, ensuring genetic diversity in their spores. This process not only sustains fungal populations but also offers tangible benefits in agriculture, medicine, and industry. Understanding and manipulating this mechanism opens doors to innovations that leverage the unique capabilities of Ascomycota, making them invaluable allies in both natural and engineered ecosystems.

Are Mold Spores Classified as VOCs? Unraveling Indoor Air Quality Concerns

You may want to see also

Spore Release: Asci rupture or open to release ascospores for wind or water dispersal

Sac fungi, or Ascomycota, are masters of containment, producing their spores—ascospores—within protective sacs called asci. These asci are not merely storage units; they are pressurized chambers designed for a dramatic release. When conditions are right, the asci rupture or open, ejecting ascospores with force, a mechanism finely tuned for dispersal by wind or water. This process is not just a passive release but an active strategy to ensure the fungi’s survival and propagation.

The rupture of asci is a precise biological event, often triggered by environmental cues such as humidity, temperature, or nutrient availability. For instance, in some species, asci swell with fluid, creating internal pressure until the sac walls can no longer contain it, leading to a sudden burst. This explosive release propels ascospores into the air, where they can travel significant distances on air currents. In aquatic environments, the rupture may be less dramatic but equally effective, allowing spores to drift with water currents to colonize new habitats.

Wind dispersal is particularly common in terrestrial sac fungi. Ascospores are lightweight and often equipped with structures like wings or ridges that enhance their aerodynamic properties. For example, the fungus *Neurospora crassa* releases ascospores that can remain airborne for hours, increasing the likelihood of reaching new substrates. To maximize this strategy, some fungi synchronize spore release during periods of high wind, a behavior observed in species like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*.

Water dispersal, on the other hand, is prevalent in aquatic or semi-aquatic species. Ascospores released into water may form a gelatinous mass that protects them during transport. This is seen in the fungus *Taphrina*, which causes leaf curl in plants. Once the spores reach a suitable environment, they germinate, ensuring the fungus’s lifecycle continues. For gardeners or farmers dealing with waterborne fungal infections, understanding this dispersal method is crucial for implementing effective control measures, such as improving drainage or using fungicides during spore release periods.

Practical tips for managing spore dispersal include monitoring environmental conditions to predict release events. For example, reducing humidity around plants can discourage ascus rupture in fungi like *Botrytis*, which thrives in damp conditions. Additionally, using windbreaks in agricultural settings can limit the spread of airborne spores. Whether in a laboratory, garden, or natural ecosystem, recognizing the role of asci rupture in spore dispersal provides valuable insights for both studying and controlling these fascinating organisms.

How Wind Disperses Spores: Exploring Nature's Aerial Seed Scattering

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, sac fungi (Ascomycota) produce spores inside a small sac-like structure called an ascus.

The spores produced by sac fungi are called ascospores, which develop and are contained within the ascus.

Typically, an ascus contains 8 ascospores, though the number can vary depending on the species.

The ascus serves as a protective structure for the developing ascospores and aids in their dispersal when mature.

While some sac fungi form visible structures like mushrooms or truffles, the individual asci are microscopic and cannot be seen without magnification.