Spores, the reproductive units of many plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are typically associated with their ability to disperse and survive in harsh conditions rather than movement. While spores themselves do not possess the capacity for self-propelled motion, they can be transported over vast distances through various mechanisms such as wind, water, animals, or even human activities. This passive movement is crucial for their survival and colonization of new habitats, ensuring the continuation of their species. However, the question of whether spores ever exhibit any form of active movement remains a fascinating area of study, as some research suggests that certain spores may respond to environmental stimuli in ways that could be interpreted as rudimentary movement, though this is still a subject of ongoing scientific investigation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Spores Move? | Spores themselves do not move actively. They are passive entities. |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Spores are dispersed through various mechanisms such as wind, water, animals, and explosive discharge (e.g., in fungi like puffballs). |

| Wind Dispersal | Many spores, especially from plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) and fungi, are lightweight and aerodynamic, allowing them to be carried over long distances by wind. |

| Water Dispersal | Some spores, particularly those of aquatic fungi and algae, are dispersed through water currents. |

| Animal Dispersal | Spores can attach to animals' fur or feathers and be transported to new locations. |

| Explosive Discharge | Certain fungi release spores with force, propelling them into the air for dispersal. |

| Passive Movement | Spores rely entirely on external forces for movement; they do not possess motility structures like flagella or cilia. |

| Survival in Environment | Spores are highly resistant and can survive harsh conditions, remaining dormant until favorable conditions for germination arise. |

| Size and Shape | Spores are typically small (micrometer scale) and vary in shape, which aids in dispersal efficiency. |

| Examples of Spores | Plant spores (e.g., pollen, fern spores), fungal spores (e.g., mold, yeast spores), bacterial spores (e.g., Bacillus spores). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Passive Movement by Wind and Water: Spores disperse via air currents, rain, or water flow over long distances

- Active Release Mechanisms: Some fungi use explosive force to eject spores into the environment

- Animal-Assisted Transport: Spores attach to animals' fur or feathers for dispersal to new areas

- Human-Induced Movement: Human activities like farming or travel spread spores globally

- Gravity-Driven Settling: Spores fall naturally under gravity, settling on nearby surfaces

Passive Movement by Wind and Water: Spores disperse via air currents, rain, or water flow over long distances

Spores, those microscopic marvels of survival, owe much of their dispersal success to the invisible forces of wind and water. These natural elements act as tireless couriers, carrying spores across vast distances with minimal energy expenditure on the part of the organism. Wind, in particular, is a primary agent of spore dispersal, especially for fungi and ferns. When released into the air, spores can be swept up into currents that transport them far beyond their origin, sometimes even across continents. This passive movement is not random but influenced by spore size, shape, and weight, which determine how long they remain airborne and how far they travel.

Consider the role of water in spore dispersal, a process equally fascinating yet distinct from wind-driven transport. Raindrops falling on spore-bearing structures, such as fungal gills or fern fronds, can dislodge spores and carry them into nearby water bodies. Once in streams, rivers, or oceans, spores may travel for miles, colonizing new habitats as they go. This method is particularly effective for aquatic fungi and algae, whose spores are adapted to withstand the rigors of water travel. For instance, certain algal spores have gelatinous coatings that protect them from desiccation and predation during their aquatic journey.

To maximize the effectiveness of passive spore dispersal, nature has evolved ingenious adaptations. Fern spores, for example, are lightweight and equipped with wing-like structures that enhance their ability to catch air currents. Similarly, fungal spores often have hydrophobic surfaces that repel water, allowing them to float on the surface of raindrops or streams without becoming waterlogged. These adaptations ensure that spores remain viable during their journey, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization once they reach a suitable environment.

Practical applications of understanding passive spore dispersal are not limited to biology. Farmers and gardeners can leverage this knowledge to manage plant diseases more effectively. For instance, knowing that fungal spores are carried by wind can inform the timing and placement of fungicide applications. Similarly, awareness of water-borne spore dispersal can guide irrigation practices to minimize the spread of pathogens. By working with, rather than against, these natural processes, we can create more resilient and sustainable ecosystems.

In conclusion, the passive movement of spores by wind and water is a testament to nature’s efficiency and ingenuity. This dispersal mechanism allows organisms to colonize new territories with minimal energy investment, ensuring their survival and proliferation. Whether through the gentle breeze or the rushing stream, spores embark on journeys that shape ecosystems and sustain life. Understanding these processes not only deepens our appreciation of the natural world but also equips us with practical tools for managing and conserving it.

Prevent Mold Growth: Can Mattress Covers Block Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Active Release Mechanisms: Some fungi use explosive force to eject spores into the environment

Spores, often perceived as passive entities waiting for wind or water to carry them, are not always at the mercy of external forces. Some fungi have evolved active release mechanisms that propel spores into the environment with remarkable precision and force. This explosive ejection ensures spores travel farther and reach more favorable habitats, increasing the chances of successful colonization. For instance, the fungus *Pilobolus* uses a unique mechanism where internal pressure builds up in a spore-containing structure, eventually bursting open and launching spores up to 2 meters away. This process is not just a random explosion but a highly coordinated event, triggered by light and humidity cues, showcasing the sophistication of fungal adaptation.

To understand the mechanics behind this phenomenon, consider the role of turgor pressure in fungal cells. Fungi like *Pilobolus* accumulate solutes within their cells, creating osmotic pressure that builds until the cell wall can no longer contain it. This pressure is then directed toward the spore-containing sporangium, acting like a biological spring. When the pressure reaches a critical point, the sporangium ruptures, and the spores are ejected at speeds up to 25 meters per second. This mechanism is so efficient that it rivals the acceleration of a bullet, though on a microscopic scale. For researchers or enthusiasts replicating this in a lab setting, observing this process under a microscope can reveal the intricate timing and force involved, offering insights into bioinspired engineering.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these active release mechanisms has applications beyond mycology. Engineers and biomimicry experts are studying such fungal strategies to develop micro-propulsion systems or drug delivery devices. For example, the concept of using osmotic pressure to create controlled explosions could inspire the design of tiny, self-propelling capsules for targeted medical treatments. Gardeners and farmers can also benefit from this knowledge by optimizing conditions for beneficial fungi, such as ensuring adequate light exposure to trigger spore release in compost or soil. However, caution is advised when handling fungi like *Pilobolus*, as their spores can cause eye irritation if ejected directly into the face.

Comparatively, while plants rely on wind, animals, or water for seed dispersal, fungi like *Pilobolus* take control of their reproductive destiny. This active approach highlights the diversity of survival strategies in the natural world. Unlike passive dispersal, which depends on unpredictable environmental factors, explosive spore ejection is a proactive measure that maximizes dispersal efficiency. For educators, this example serves as a compelling case study to illustrate the principles of adaptation and biomechanics in biology classes. Students can even conduct simple experiments, such as growing *Pilobolus* on dung or decaying matter, to observe the explosive mechanism firsthand, fostering curiosity about the hidden dynamics of fungal life.

In conclusion, the explosive release of spores by certain fungi is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. By harnessing internal pressure and environmental cues, these organisms ensure their survival and propagation in ways that defy passive expectations. Whether for scientific research, technological innovation, or educational purposes, studying these active release mechanisms opens doors to new discoveries and applications. Next time you encounter a fungus, remember that beneath its unassuming exterior may lie a microscopic powerhouse, ready to launch its spores into the world with precision and force.

Exploring the Myth: Are Ghosts Immune to Spore Attacks?

You may want to see also

Animal-Assisted Transport: Spores attach to animals' fur or feathers for dispersal to new areas

Spores, often perceived as stationary entities waiting for wind or water to carry them, have a more dynamic dispersal strategy than commonly assumed. One fascinating method is animal-assisted transport, where spores hitch a ride on the fur or feathers of animals to reach new habitats. This symbiotic relationship benefits both the spore-producing organism and the animal, though the latter is often an unwitting participant. For instance, fungi like those in the genus *Ascomycota* produce sticky spores that easily adhere to passing mammals or birds. This mechanism ensures that spores travel farther and more efficiently than they could through passive means alone.

Consider the practical implications of this process for gardeners or conservationists. If you’re reintroducing a plant species to a degraded area, strategically placing spore-producing plants near animal pathways can enhance dispersal. For example, placing *Pteris vittata* (a fern known for its arsenic-remediating properties) near deer trails can increase its spread in contaminated areas. Similarly, in agricultural settings, understanding animal movement patterns can optimize the distribution of beneficial fungi that improve soil health. A cautionary note: ensure the spores are non-toxic to the animals involved, as some species can harm wildlife if ingested or inhaled.

From a comparative perspective, animal-assisted transport is more targeted than wind dispersal, which scatters spores indiscriminately. Animals tend to follow predictable routes, such as migratory paths or foraging trails, allowing spores to reach specific microhabitats. For example, birds migrating between forests can carry spores of tree fungi, facilitating cross-pollination between distant ecosystems. This precision makes animal transport particularly effective for species that thrive in niche environments. However, it’s less reliable than water dispersal in aquatic ecosystems, where currents provide consistent movement.

To harness this mechanism effectively, follow these steps: first, identify the animals frequenting your target area—camera traps or footprint tracking can help. Second, select spore-producing plants or fungi that have adhesive or hook-like structures suited for attachment. Third, position these organisms along animal pathways, ensuring they’re accessible without disrupting natural behavior. For instance, placing spore-bearing mushrooms at the base of trees where squirrels climb can increase adherence. Finally, monitor dispersal over time using spore traps or genetic analysis to track colonization patterns.

The takeaway is clear: animal-assisted transport is a strategic, underutilized method for spore dispersal. By understanding and leveraging this natural process, we can enhance ecological restoration, agricultural productivity, and even the spread of beneficial microorganisms. Whether you’re a conservationist, farmer, or hobbyist, incorporating this knowledge into your practices can yield significant results. Just remember to prioritize the well-being of the animals involved, ensuring their role as spore carriers remains harmless and mutually beneficial.

Exploring the Microscopic World: Can You Visualize a Spore's Image?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Human-Induced Movement: Human activities like farming or travel spread spores globally

Spores, those microscopic survivalists of the plant and fungal worlds, are not inherently mobile. Yet, human activities have become a powerful force in their global dispersal, reshaping ecosystems and agricultural practices in profound ways. Farming, for instance, is a prime example. Tilling soil releases dormant spores buried deep beneath the surface, exposing them to wind and water currents that carry them far beyond their original location. A single plow can disturb millions of spores per acre, each capable of germinating under favorable conditions. This process, while unintentional, has led to the spread of both beneficial and harmful species, from mycorrhizal fungi that enhance crop growth to pathogens like *Phytophthora infestans*, the infamous cause of the Irish potato famine.

Travel, another cornerstone of human activity, acts as a spore superhighway. Air travel alone moves billions of passengers annually, each potentially carrying spores on clothing, luggage, or even in their respiratory systems. A study published in *Nature Microbiology* found that airline routes correlate strongly with the global spread of fungal pathogens, such as *Aspergillus* and *Candida*. Similarly, maritime trade introduces spores through ballast water and cargo, as seen with the invasive chytrid fungus *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, which has decimated amphibian populations worldwide. Even recreational activities like hiking or gardening can inadvertently transport spores across regions, as soil particles cling to boots or tools.

The implications of this human-induced movement are far-reaching. In agriculture, the introduction of non-native spores can disrupt local ecosystems, outcompete indigenous species, or introduce diseases to crops without natural resistance. For example, the spread of *Fusarium* spores through contaminated grain shipments has led to widespread wheat blight in regions where the fungus was previously unknown. Conversely, intentional spore dispersal, such as the use of mycorrhizal inoculants to improve soil health, demonstrates the potential for positive outcomes when managed carefully. However, the line between beneficial and harmful is often thin, requiring rigorous monitoring and regulation.

To mitigate the risks of unintended spore dispersal, practical steps can be taken. Farmers can adopt no-till or reduced-tillage practices to minimize soil disturbance, preserving spore banks in situ. Travelers can clean equipment and footwear before moving between regions, particularly when visiting ecologically sensitive areas. International regulations, such as the International Maritime Organization’s ballast water management guidelines, aim to reduce the spread of invasive species, including spore-producing organisms. For individuals, awareness is key: understanding the role of human activities in spore movement empowers us to act responsibly, whether in the garden, on the trail, or at the airport.

Ultimately, human-induced spore movement is a double-edged sword, offering both opportunities and challenges. By recognizing our role as agents of dispersal, we can harness this knowledge to foster healthier ecosystems and more resilient agriculture. Yet, without careful management, the same processes that connect us globally can also sow the seeds of ecological disruption. The choice lies in how we choose to move—and what we carry with us.

Troubleshooting Spore Code Redemption Issues on Steam: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

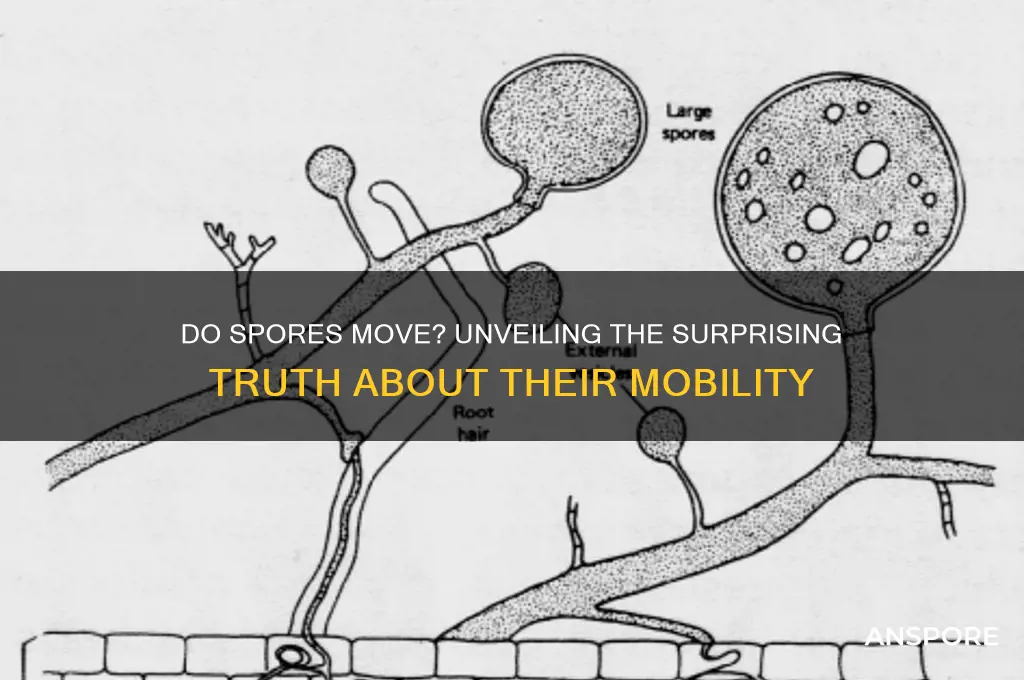

Gravity-Driven Settling: Spores fall naturally under gravity, settling on nearby surfaces

Spores, those microscopic marvels of survival, often rely on the simplest of forces to disperse: gravity. Unlike active swimmers like sperm or flyers like winged seeds, spores don’t propel themselves. Instead, they fall naturally, a process known as gravity-driven settling. This passive mechanism ensures that spores released from fungi, ferns, or bacteria land on nearby surfaces, where they can germinate under favorable conditions. Imagine a dandelion clock releasing its seeds—while wind aids some, gravity pulls others straight down, a silent, steady force shaping their journey.

To visualize this, consider a spore released from a mushroom cap. Once detached, it begins a slow descent, influenced only by its mass and the pull of Earth’s gravity. The distance it travels depends on its size and shape; smaller spores settle more slowly, drifting farther in still air, while larger ones drop quickly, landing closer to their source. This natural settling is why you’ll often find fungal growths spreading in concentric circles—a testament to gravity’s role in spore dispersal. For gardeners or mycologists, understanding this pattern can help predict where mold or mushrooms might appear next.

Practical applications of gravity-driven settling abound. In indoor environments, spores from mold or mildew tend to accumulate on lower surfaces first—think basement floors or the undersides of furniture. To mitigate this, regular cleaning of these areas is essential, especially in humid conditions where spores thrive. A simple tip: wipe down surfaces with a damp cloth weekly, focusing on areas within a foot of the ground. For larger spaces, like greenhouses, elevating plants slightly can reduce spore buildup on soil surfaces, improving air circulation and plant health.

Comparatively, gravity-driven settling contrasts with other dispersal methods like wind or water, which carry spores over greater distances. Yet, its reliability in close-range colonization is unmatched. For instance, while wind might scatter fern spores across a forest, gravity ensures that those released near a decaying log land precisely where nutrients are abundant. This localized efficiency makes gravity-driven settling a cornerstone of spore survival strategies, particularly in stable environments where long-distance travel isn’t necessary.

In conclusion, gravity-driven settling is a quiet yet powerful mechanism in the life cycle of spores. By understanding how spores fall and where they land, we can better manage their presence in our homes, gardens, and natural habitats. Whether you’re combating mold or cultivating fungi, recognizing the role of gravity offers practical insights into controlling and harnessing this natural process. After all, even the smallest spores are subject to the largest forces.

Where to Buy Truffle Spores for Successful Cultivation at Home

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores themselves do not move on their own; they are passive and rely on external forces like wind, water, or animals for dispersal.

Yes, spores can move through the air when carried by wind currents, which is a common method of dispersal for many plants and fungi.

Spores can move in water if they are suspended in currents or carried by flowing water, which is a key dispersal method for aquatic organisms like algae.