Spores, the resilient reproductive structures produced by various organisms such as fungi, plants, and some bacteria, are often studied for their ability to survive harsh environmental conditions. A common question that arises in biological discussions is whether spores contain mitochondria, the cellular organelles responsible for energy production. While spores are metabolically dormant and have reduced cellular activity, they do retain mitochondria, albeit in a less active state. These mitochondria play a crucial role in the spore's ability to revive and resume growth when conditions become favorable, highlighting their importance even in this dormant phase. Understanding the presence and function of mitochondria in spores provides valuable insights into their survival mechanisms and metabolic processes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Presence of Mitochondria | Spores do not have functional mitochondria in their dormant state. |

| Energy Source | Rely on stored lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates for energy. |

| Metabolic Activity | Minimal to no metabolic activity during dormancy. |

| Respiration | Aerobic respiration is absent or significantly reduced. |

| Cellular Structure | Simplified structure with thick cell walls for protection. |

| Function | Serve as a survival mechanism for harsh conditions. |

| Activation | Mitochondria may become active upon germination and re-entry into metabolism. |

| Examples | Found in bacteria (endospores), fungi, plants, and some protists. |

| Size | Typically small and lightweight for dispersal. |

| Genetic Material | Contain genetic material but lack active organelles like mitochondria. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mitochondrial presence in fungal spores

Fungal spores, the resilient structures responsible for dispersal and survival, often raise questions about their cellular composition. One critical aspect is the presence of mitochondria, the powerhouse of eukaryotic cells. Mitochondria are essential for energy production, but their role in fungal spores is uniquely adapted to the spore's dormant and resilient nature. Unlike actively growing fungal cells, spores typically contain fewer mitochondria, which are often in a quiescent state, conserving energy for germination when conditions become favorable.

Analyzing the mitochondrial presence in fungal spores reveals a strategic balance between energy conservation and readiness for activation. During sporulation, mitochondria undergo morphological changes, reducing in number and size, yet retaining the capacity to resume function rapidly. For example, *Aspergillus niger* spores exhibit mitochondria with condensed cristae, a structural adaptation that minimizes energy expenditure while maintaining viability. This adaptation ensures that spores can survive harsh environments, such as extreme temperatures or desiccation, for extended periods without compromising their ability to germinate.

From a practical standpoint, understanding mitochondrial dynamics in fungal spores has implications for industries like agriculture and medicine. For instance, controlling spore germination by targeting mitochondrial activity could lead to more effective fungicides. Researchers have explored compounds that disrupt mitochondrial function in spores, such as strobilurin fungicides, which inhibit electron transport and prevent germination. These applications highlight the importance of mitochondria as a critical target for managing fungal pathogens while minimizing harm to beneficial organisms.

Comparatively, the mitochondrial content in fungal spores differs significantly from that of plant or bacterial spores. While plant spores often retain active mitochondria to support rapid germination, fungal spores prioritize longevity over immediate energy availability. Bacterial spores, being prokaryotic, lack mitochondria altogether, relying instead on alternative metabolic pathways. This distinction underscores the evolutionary specialization of fungal spores, where mitochondria play a dual role: preserving viability during dormancy and enabling swift activation upon germination.

In conclusion, the mitochondrial presence in fungal spores is a finely tuned adaptation that balances survival and readiness. By studying these organelles, scientists can develop targeted strategies for controlling fungal growth and enhancing spore preservation. Whether in agricultural pest management or pharmaceutical development, the unique mitochondrial characteristics of fungal spores offer valuable insights into their biology and potential vulnerabilities.

Do Spores Actively Grow and Divide? Unraveling Their Dormant Nature

You may want to see also

Bacterial spores and energy production

Bacterial spores are metabolically dormant forms that lack the active energy production machinery found in vegetative cells. Unlike their active counterparts, spores do not possess mitochondria, the organelles responsible for ATP synthesis in eukaryotic cells. Instead, they rely on a minimal metabolic state to survive harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation. This dormancy is a survival strategy, not a state of energy production. Spores conserve energy by halting most biochemical processes, ensuring long-term viability without the need for continuous ATP generation.

To understand energy production in bacterial spores, consider their unique structure. Spores are encased in a protective coat and cortex, which act as barriers to environmental stressors. During sporulation, the cell synthesizes dipicolinic acid (DPA), a molecule that binds calcium ions and stabilizes the spore’s DNA and proteins. This process requires energy, but once complete, the spore enters a quiescent state. Any residual ATP from sporulation is stored for minimal maintenance, not active metabolism. Thus, spores do not produce energy in the traditional sense; they are energy-efficient survival capsules.

A practical example of spore energy dynamics is observed in *Bacillus subtilis*, a model organism for sporulation studies. During sporulation, the mother cell degrades its own DNA and proteins to provide nutrients for the developing spore. This process is energetically costly but ensures the spore’s long-term survival. Once formed, the spore’s metabolic rate drops to near-zero, with no detectable ATP production. Reactivation occurs only when conditions improve, triggering germination and a return to vegetative growth. This cycle highlights the spore’s role as an energy-conserving, not energy-producing, entity.

For those studying or working with bacterial spores, understanding their energy limitations is crucial. Spores cannot be cultured or manipulated using metabolic inhibitors targeting mitochondria, as they lack these structures. Instead, focus on environmental triggers like nutrient availability, pH, and temperature to induce germination. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores germinate in the presence of specific amino acids and reducing agents, a process that reactivates metabolism. Practical tips include using heat shock (70–80°C for 10–20 minutes) to break spore dormancy in laboratory settings, ensuring accurate experimentation and industrial applications like food preservation.

In summary, bacterial spores are not energy producers but energy conservers. Their survival strategy revolves around metabolic dormancy, not active ATP synthesis. By focusing on their unique structure and reactivation mechanisms, researchers and practitioners can effectively study and control spore behavior. This knowledge is essential for fields ranging from microbiology to biotechnology, where understanding spore resilience is key to both harnessing and combating these remarkable organisms.

Mold Spores and Vertigo: Unraveling the Hidden Connection to Dizziness

You may want to see also

Plant spore cellular structure

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are marvels of cellular simplicity and durability. Unlike complex plant cells, spores are stripped down to essentials, yet they retain the capacity to survive harsh conditions and germinate into new organisms. Central to their functionality is their cellular structure, which balances minimalism with efficiency. One critical question arises: do plant spores, in their streamlined form, contain mitochondria? The answer lies in understanding their unique cellular architecture.

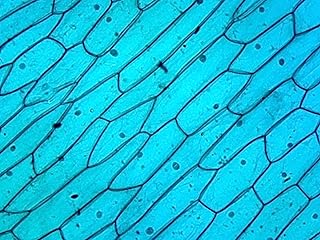

Plant spores, particularly those of ferns, mosses, and seedless vascular plants, exhibit a cellular structure optimized for survival rather than immediate growth. Their cytoplasm is densely packed with nutrients, such as starch grains and lipids, which serve as energy reserves during dormancy. The cell wall, composed of sporopollenin, provides unparalleled protection against desiccation, UV radiation, and mechanical stress. Notably, plant spores do indeed possess mitochondria, though these organelles are often fewer in number and less active compared to those in vegetative cells. This reduction reflects the spore’s quiescent state, where energy demands are minimal until germination is triggered.

The presence of mitochondria in plant spores is not merely incidental but functionally significant. During dormancy, mitochondrial activity is suppressed to conserve resources, but upon exposure to favorable conditions—such as water, light, or warmth—these organelles rapidly resume their role in ATP production. This metabolic reactivation is crucial for powering the initial stages of germination, including cell division and the emergence of the embryonic plant. Interestingly, some studies suggest that mitochondrial DNA in spores may also play a role in genetic diversity, contributing to the adaptability of spore-producing plants in varying environments.

For practical applications, understanding the mitochondrial dynamics in plant spores can inform agricultural and conservation efforts. For instance, seed banks that preserve plant species often rely on the longevity of spores, which can remain viable for decades or even centuries. Maintaining optimal storage conditions—low temperature, reduced oxygen, and controlled humidity—helps preserve mitochondrial integrity, ensuring successful germination when needed. Additionally, researchers exploring mitochondrial function in spores may uncover new strategies for enhancing crop resilience or developing stress-tolerant plant varieties.

In summary, plant spores are not devoid of mitochondria; rather, they harbor a specialized, energy-efficient mitochondrial system tailored to their survival and reproductive roles. This cellular structure exemplifies nature’s ingenuity, blending simplicity with functionality. Whether in the lab or the field, appreciating the intricacies of spore biology opens doors to innovations in plant science and conservation.

Can Air Filters Effectively Trap and Prevent Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mitochondrial function in spore germination

Spores, the resilient survival structures of fungi, algae, and certain plants, are often dormant and metabolically inactive. Yet, upon germination, they undergo a rapid transition to active growth, requiring a surge in energy production. This is where mitochondria, the cellular powerhouses, play a pivotal role. Mitochondria are present in spores, albeit in a quiescent state, and their activation is critical for successful germination. During dormancy, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and proteins are preserved but minimally functional. Upon exposure to favorable conditions—such as water, nutrients, and appropriate temperature—mitochondria resume ATP production, fueling the metabolic processes necessary for spore revival.

The activation of mitochondria during germination is a tightly regulated process. In fungi like *Aspergillus nidulans*, mitochondrial biogenesis is triggered by the uptake of glucose, which signals the spore to exit dormancy. This involves the synthesis of new mitochondrial proteins and the restoration of the electron transport chain (ETC). Interestingly, spores of *Neurospora crassa* rely on stored glycogen, which is rapidly metabolized to provide the initial energy burst for mitochondrial activation. This highlights the species-specific strategies spores employ to ensure mitochondrial function is restored efficiently.

One critical aspect of mitochondrial function in spore germination is the repair of oxidative damage. Spores often endure harsh conditions that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage mitochondrial membranes and DNA. During germination, spores activate repair mechanisms, including the upregulation of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase. For instance, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* spores, the expression of *SOD2*, a mitochondrial SOD, increases significantly within the first hour of germination, safeguarding mitochondrial integrity.

Practical applications of understanding mitochondrial function in spore germination extend to agriculture and biotechnology. For example, seed coatings enriched with mitochondrial cofactors like coenzyme Q10 or alpha-lipoic acid can enhance germination rates in crops like rice and wheat. Additionally, in fungal biocontrol agents, such as *Trichoderma*, optimizing mitochondrial health during spore production improves their efficacy in suppressing plant pathogens. Researchers also explore mitochondrial inhibitors as potential fungicides, targeting spore germination without harming plants.

In conclusion, mitochondria are not passive bystanders in spore germination but active participants in the transition from dormancy to growth. Their role in energy production, damage repair, and signaling underscores their importance in this critical life stage. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can develop innovative strategies to improve crop yields, combat fungal diseases, and harness spores for biotechnological applications. Understanding mitochondrial function in spores is thus a key to unlocking their full potential.

Growing Spores in Subnautica: Tips and Tricks for Success

You may want to see also

Comparison of spore and cell mitochondria

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain organisms, lack mitochondria in their dormant state. This absence is a key adaptation for enduring harsh conditions, as mitochondria are energy-demanding organelles vulnerable to damage. In contrast, vegetative cells of the same organisms, such as fungal hyphae or bacterial cells, contain active mitochondria essential for ATP production and metabolic processes. This fundamental difference highlights how spores prioritize longevity over immediate energy needs, shedding light on their remarkable ability to withstand extreme environments.

To understand this comparison, consider the lifecycle of a fungus like *Aspergillus*. During active growth, its cells rely on mitochondria to fuel processes like nutrient uptake and reproduction. However, when conditions deteriorate, the fungus produces spores that enter a quiescent state, devoid of mitochondria. This mitochondrial absence is not permanent; upon germination, spores regenerate mitochondria, a process requiring pre-stored mitochondrial DNA and proteins. This dynamic underscores the strategic trade-off between energy efficiency and survival in spore-forming organisms.

From a practical standpoint, this mitochondrial disparity has implications for industries like food preservation and medicine. For instance, targeting mitochondrial function in vegetative cells is a common strategy for antifungal agents, as disrupting ATP production halts growth. Spores, however, are inherently resistant to such treatments due to their mitochondrial-free state. Understanding this difference can guide the development of more effective preservation methods or antimicrobial therapies, particularly for spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum*.

A closer examination reveals that spores are not entirely devoid of mitochondrial remnants. Some species retain mitochondrial DNA or proteins in a dormant form, ready to reactivate upon germination. This contrasts with vegetative cells, where mitochondria are fully functional and dynamically regulated. For example, in *Bacillus subtilis*, spores store mitochondrial components in a condensed state, allowing rapid reassembly during revival. This nuanced comparison highlights the sophisticated mechanisms spores employ to balance survival and metabolic readiness.

In summary, the comparison of spore and cell mitochondria reveals a striking adaptation to environmental challenges. While vegetative cells depend on active mitochondria for energy and growth, spores sacrifice immediate metabolic capability for long-term survival. This distinction not only explains spores' resilience but also offers practical insights for combating spore-forming organisms in various contexts. By focusing on this unique mitochondrial dynamic, researchers and practitioners can develop more targeted and effective strategies.

Anaerobic Bacteria and Sporulation: Do All Species Form Spores?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores do have mitochondria. Mitochondria are essential organelles for energy production and are present in the cells of most eukaryotic organisms, including those that produce spores.

During dormancy, the metabolic activity of spores is significantly reduced, and mitochondria become less active. However, they are not completely inactive and can resume function when the spore germinates.

Only eukaryotic spores, such as those from fungi and plants, have mitochondria. Bacterial spores, being prokaryotic, lack mitochondria and instead rely on their cell membrane for energy production.