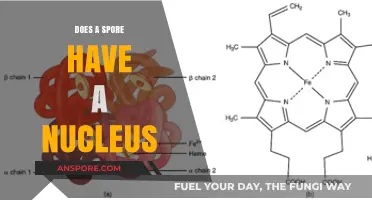

Spores, the reproductive structures of certain plants, fungi, and bacteria, are often associated with their ability to survive harsh conditions and disperse widely. A common question that arises is whether a spore contains a nucleus, a critical component of eukaryotic cells that houses genetic material. In eukaryotic organisms, such as plants and fungi, spores typically do contain a nucleus, as they are part of the organism's life cycle and carry the genetic information necessary for growth and development. However, in prokaryotic organisms like bacteria, which produce structures called endospores, there is no true nucleus, as their genetic material is not enclosed within a membrane-bound organelle. Understanding the presence or absence of a nucleus in spores is essential for grasping their function, resilience, and role in the reproductive strategies of different organisms.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Structure Basics: Spores are reproductive cells with protective walls, but do they contain a nucleus

- Nucleus in Spores: Most spores house a nucleus, essential for genetic material storage and reproduction

- Types of Spores: Fungal, bacterial, and plant spores vary; all typically contain a nucleus

- Function of Nucleus: The nucleus in spores directs cell division and inheritance during germination

- Exceptions in Spores: Some spores, like bacterial endospores, lack a nucleus, serving only as survival structures

Spore Structure Basics: Spores are reproductive cells with protective walls, but do they contain a nucleus?

Spores, often likened to nature’s survival capsules, are reproductive cells encased in protective walls designed to endure harsh conditions. These walls, composed of resilient materials like sporopollenin, shield the spore’s internal contents from heat, desiccation, and chemicals. But what lies within this armor? The question of whether spores contain a nucleus is pivotal, as it distinguishes them from other cellular structures and reveals their role in reproduction. Unlike vegetative cells, which actively participate in growth and metabolism, spores are dormant entities primed for dispersal and germination under favorable conditions.

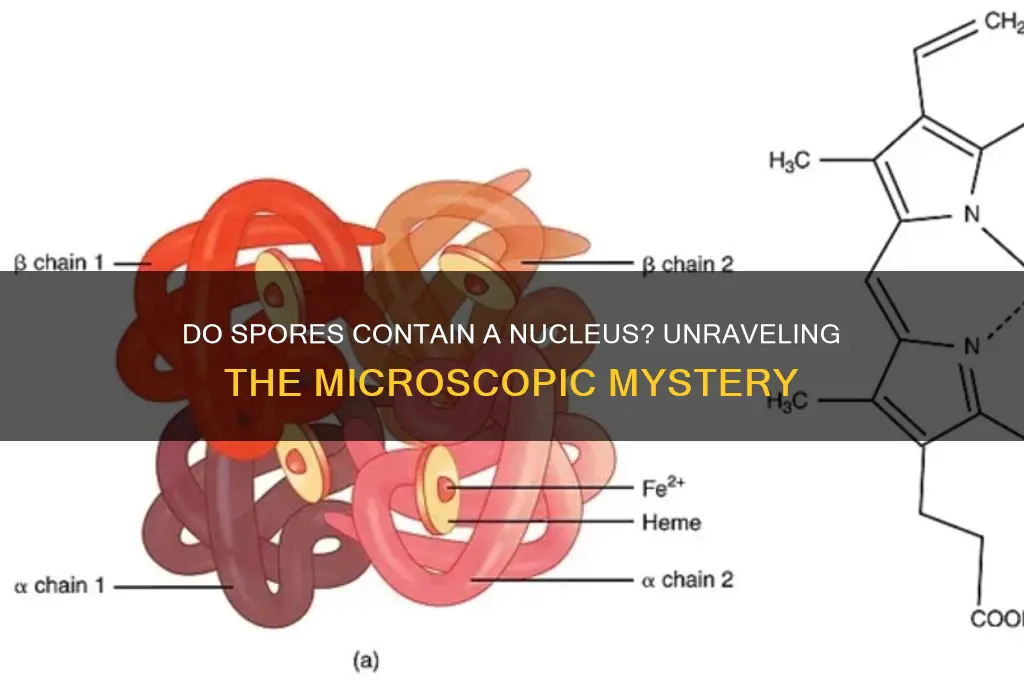

To address the nucleus question, consider the spore’s life cycle. In fungi and plants, spores are typically haploid cells, meaning they carry a single set of chromosomes. This genetic material is indeed housed within a nucleus, though the nucleus is often condensed and metabolically inactive during dormancy. For example, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium* retain a nucleus, which reactivates upon germination to initiate growth. Similarly, plant spores, such as those from ferns or mosses, contain a nucleus that directs development into a new organism. Thus, the presence of a nucleus is fundamental to the spore’s function as a reproductive unit.

However, not all spores are created equal. Bacterial endospores, formed by certain genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, present an exception. These structures are not true cells but rather DNA-containing compartments encased in multiple protective layers. While they lack a conventional nucleus, their core houses the bacterial chromosome and essential enzymes in a dehydrated, dormant state. This distinction highlights the diversity of spore structures across organisms, emphasizing the need to specify the type of spore in question when discussing nuclear presence.

Practical implications of this knowledge arise in fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, understanding that plant spores contain a nucleus aids in seed bank strategies, ensuring genetic material remains viable for future generations. In medicine, recognizing the nuclear absence in bacterial endospores guides sterilization techniques, as these structures require extreme conditions (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes) to be eradicated. Conversely, fungal spores’ nuclear content informs antifungal treatments, targeting metabolic reactivation during germination.

In conclusion, spores universally serve as reproductive units, but their nuclear status varies by organism. Fungal and plant spores retain a nucleus, essential for their developmental potential, while bacterial endospores house genetic material without a true nucleus. This distinction underscores the adaptability of spores across biological kingdoms and informs practical applications in science and industry. Whether studying spore dispersal in ecosystems or combating spore-forming pathogens, clarity on their structure is key to harnessing their potential and mitigating their risks.

Mold Spores and Fatigue: Uncovering the Hidden Link to Tiredness

You may want to see also

Nucleus in Spores: Most spores house a nucleus, essential for genetic material storage and reproduction

Spores, the resilient survival structures of many fungi, plants, and some bacteria, are often likened to microscopic time capsules. Central to their function is the nucleus, a feature present in most spores. This nucleus is not merely a passive storage unit but a dynamic hub that safeguards genetic material, ensuring the spore’s ability to regenerate into a new organism under favorable conditions. Without it, the spore’s capacity for reproduction and species continuity would be severely compromised.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a plant that relies on spores for reproduction. Each spore contains a nucleus that carries half the genetic material needed for growth. When conditions are right—adequate moisture, light, and temperature—the spore germinates, and the nucleus directs cell division, ultimately forming a new fern. This process underscores the nucleus’s role as the architect of genetic inheritance, a blueprint for life encoded within the spore’s compact structure.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the nucleus in spores has implications for fields like agriculture and medicine. For instance, fungal spores with intact nuclei are more likely to colonize crops, making them targets for antifungal treatments. In laboratories, researchers manipulate spore nuclei to study genetic resilience, a technique crucial for developing spore-based vaccines or preserving endangered plant species. Knowing the nucleus’s role allows for precise interventions, whether preventing unwanted growth or fostering desired outcomes.

Comparatively, not all spores house a nucleus. Some bacterial spores, like those of *Bacillus anthracis*, lack a true nucleus, instead relying on a condensed nucleoid region. This distinction highlights the diversity of spore structures and the evolutionary adaptations that prioritize survival over uniformity. Yet, for the majority of spore-producing organisms, the nucleus remains a non-negotiable component, a testament to its indispensable role in genetic continuity.

In essence, the nucleus in spores is more than a storage compartment—it’s the linchpin of their reproductive strategy. Its presence ensures that genetic material is preserved, replicated, and transmitted with fidelity, enabling spores to endure harsh environments and emerge as new life when conditions permit. Whether in a fern’s lifecycle or a fungal colony, the nucleus exemplifies nature’s ingenuity in packaging potential within the confines of a microscopic cell.

Do Cocci Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth About These Bacteria

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Fungal, bacterial, and plant spores vary; all typically contain a nucleus

Spores, the resilient survival structures of various organisms, exhibit remarkable diversity across fungi, bacteria, and plants. Despite their differences, a unifying feature is the presence of a nucleus, which houses genetic material essential for growth and reproduction. This nucleus is often encased in a protective layer, enabling spores to endure harsh conditions until favorable environments trigger germination. Understanding the types of spores and their nuclear characteristics provides insight into their ecological roles and survival strategies.

Fungal Spores: Masters of Dispersal

Fungal spores, such as those produced by molds and mushrooms, are among the most common and varied. These spores typically contain a single nucleus, though some species may have multinucleate spores. For example, *Aspergillus* produces conidia with a single nucleus, while *Rhizopus* spores may contain multiple nuclei. Fungal spores are lightweight and often dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Their nucleus remains dormant until conditions like moisture and warmth signal germination, allowing fungi to colonize new habitats efficiently.

Bacterial Spores: Survival in Extremes

Bacterial spores, most notably those of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are renowned for their extreme resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. Unlike fungal and plant spores, bacterial spores are not reproductive structures but rather dormant forms of the bacterium. Each bacterial spore contains a nucleus-like region called a nucleoid, which holds the organism’s DNA. This compact, dehydrated structure is encased in multiple protective layers, including a thick spore coat and cortex. Bacterial spores can remain viable for centuries, germinating only when nutrients and favorable conditions are present.

Plant Spores: The Life Cycle Link

Plant spores, such as those of ferns, mosses, and ferns, play a critical role in the alternation of generations in their life cycles. These spores typically contain a single haploid nucleus, which divides upon germination to form a gametophyte. For instance, fern spores develop into small, heart-shaped gametophytes that produce eggs and sperm. Plant spores are often dispersed by wind or water, and their nucleus remains protected by a tough outer wall. This design ensures genetic continuity and adaptability across diverse environments.

Practical Implications and Takeaways

Understanding the nuclear composition of spores has practical applications in fields like agriculture, medicine, and environmental science. For example, fungal spores with intact nuclei are indicators of air quality, while bacterial spores are targets for sterilization processes in healthcare. Plant spores, with their haploid nuclei, are essential for breeding programs and ecological restoration. By recognizing the nucleus as a common thread among spore types, scientists can develop strategies to harness their benefits or mitigate their risks, from preserving biodiversity to preventing food spoilage.

In summary, while fungal, bacterial, and plant spores differ in structure, function, and life cycle, their nuclei are central to their survival and reproduction. This shared feature underscores the adaptability of spores across biological kingdoms, making them fascinating subjects for study and application.

Mold Spores and Sore Throats: Uncovering the Hidden Connection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Function of Nucleus: The nucleus in spores directs cell division and inheritance during germination

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain organisms, contain a nucleus that plays a pivotal role in their lifecycle. This nucleus is not merely a passive storage unit for genetic material but an active director of cellular processes. During germination, the nucleus orchestrates cell division, ensuring the spore develops into a new organism. It also governs the inheritance of genetic traits, maintaining the continuity of the species. Without this nuclear control, spores would lack the precision needed to transition from dormancy to active growth.

Consider the process of germination as a carefully choreographed dance. The nucleus acts as the lead dancer, signaling when and how cells should divide. This is achieved through the regulation of gene expression, where specific genes are activated or suppressed to guide development. For instance, genes responsible for cell cycle progression are upregulated, while those inhibiting growth are downregulated. This precise control ensures that the spore’s limited resources are efficiently utilized, maximizing the chances of successful germination.

Practical insights into this process can be drawn from fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus niger*. During germination, the nucleus rapidly reorganizes its chromatin structure, making essential genes accessible for transcription. Researchers have observed that inhibiting nuclear function, such as disrupting DNA replication, halts germination entirely. This highlights the nucleus’s indispensable role in translating genetic information into actionable cellular processes. For those studying spore biology, focusing on nuclear dynamics can provide critical insights into optimizing germination rates, particularly in agricultural or biotechnological applications.

A comparative analysis reveals that the nucleus in spores shares functional similarities with that of vegetative cells but operates under unique constraints. Unlike cells in actively growing organisms, spores must conserve energy during dormancy, yet be ready to spring into action upon germination. The nucleus achieves this by maintaining a condensed genome, which is rapidly activated when conditions are favorable. This dual requirement for quiescence and responsiveness underscores the nucleus’s adaptability, a trait that has evolutionary advantages for spore-producing organisms.

In conclusion, the nucleus in spores is far more than a repository of DNA; it is the mastermind behind germination. By directing cell division and ensuring accurate genetic inheritance, it bridges the gap between dormancy and active life. Understanding this function not only deepens our appreciation of spore biology but also opens avenues for practical applications, from improving crop resilience to developing novel preservation techniques. The nucleus, in essence, is the linchpin of spore survival and proliferation.

Can Bacterial Spores Multiply? Unveiling Their Dormant Survival Mechanism

You may want to see also

Exceptions in Spores: Some spores, like bacterial endospores, lack a nucleus, serving only as survival structures

Spores are often misunderstood as miniature, dormant versions of the organisms they originate from, complete with a nucleus. However, this generalization overlooks a critical exception: bacterial endospores. Unlike spores from fungi or plants, which retain a nucleus, bacterial endospores are nucleus-free. These structures are not miniature cells but rather highly specialized survival mechanisms. Produced by certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, endospores serve as a last resort for enduring extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. Their lack of a nucleus is not an oversight but a strategic adaptation, allowing them to minimize metabolic activity and maximize durability.

To understand why bacterial endospores forgo a nucleus, consider their primary function: survival, not immediate reproduction. A nucleus, with its genetic material and associated machinery, is resource-intensive and vulnerable to damage. By eliminating it, endospores reduce their metabolic needs to near zero, enabling them to persist in environments that would destroy most life forms. For example, *Bacillus anthracis* endospores can survive in soil for decades, waiting for favorable conditions to reactivate. This nucleus-free design is a trade-off—sacrificing immediate functionality for long-term resilience.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of a nucleus in bacterial endospores has significant implications for sterilization and disinfection. Standard methods like boiling water (100°C) are insufficient to destroy endospores; they require autoclaving at 121°C and 15 psi for at least 15 minutes. This is why medical equipment and lab materials must undergo such rigorous treatment. For home applications, pressure cookers can achieve similar results, but ensuring the correct temperature and duration is critical. Understanding this exception in spore biology is essential for anyone working in healthcare, food safety, or microbiology.

Comparatively, fungal and plant spores retain a nucleus, enabling them to germinate and grow immediately upon landing in a suitable environment. This difference highlights the divergent evolutionary strategies of bacteria versus eukaryotes. While fungal spores, like those of *Aspergillus*, are ready to sprout within hours under optimal conditions, bacterial endospores remain dormant until triggered by specific cues, such as nutrient availability or pH changes. This contrast underscores the uniqueness of endospores as survival specialists rather than immediate colonizers.

In conclusion, the exception of bacterial endospores challenges the assumption that all spores contain a nucleus. Their nucleus-free design is a testament to the ingenuity of nature in solving survival challenges. For professionals and enthusiasts alike, recognizing this distinction is key to effective sterilization, contamination control, and appreciation of microbial diversity. Whether in a lab, kitchen, or field, understanding this exception transforms how we approach spore-related tasks and problems.

Steel Types and Spore Absorption: Unraveling the Myth and Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, a spore contains a nucleus, which houses its genetic material.

The nucleus in a spore stores and protects the organism's DNA, ensuring it can survive harsh conditions and germinate when favorable conditions return.

Yes, all spores, whether from fungi, plants, or bacteria, contain a nucleus or equivalent genetic material storage structure.

The nucleus in a spore is often more resilient and metabolically inactive, allowing the spore to remain dormant for extended periods until conditions are suitable for growth.