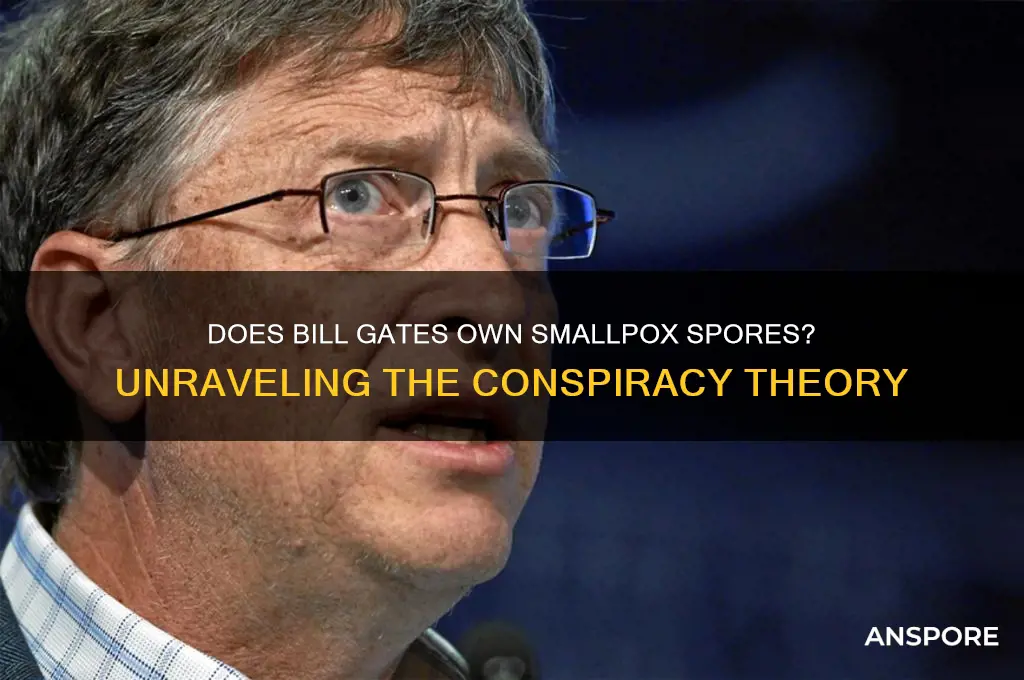

The question of whether Bill Gates owns smallpox spores has surfaced in various conspiracy theories and misinformation campaigns, often tied to unfounded claims about his involvement in global health initiatives. Smallpox, a deadly disease eradicated in 1980, is stored in highly secure laboratories under strict international regulations, primarily at the CDC in the United States and VECTOR Institute in Russia. Bill Gates, through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, has funded global health programs, including vaccine development and disease prevention, but there is no credible evidence linking him to the possession or distribution of smallpox spores. Such claims are baseless and appear to exploit public mistrust and fear, highlighting the broader issue of misinformation in the digital age.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ownership of Smallpox Spores | No credible evidence or official records indicate Bill Gates owns smallpox spores. |

| Bill Gates' Involvement in Smallpox | Gates' foundation (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) supports global health initiatives, including disease eradication and vaccine research, but not smallpox spore ownership. |

| Smallpox Eradication | Smallpox was eradicated globally in 1980, with the last known natural case in 1977. WHO oversees remaining lab stocks for research. |

| Lab Stocks of Smallpox | Smallpox virus samples are stored in secure labs at the CDC (Atlanta, USA) and VECTOR Institute (Koltsovo, Russia) under WHO supervision. |

| Conspiracy Theories | Misinformation links Gates to smallpox spores, often tied to unfounded claims about vaccine control or bioweapons. No evidence supports these claims. |

| Gates' Philanthropy Focus | The Gates Foundation focuses on polio eradication, malaria, HIV/AIDS, and COVID-19 vaccines, not smallpox-related activities. |

| Legal Status of Smallpox Ownership | Possession of smallpox virus outside authorized labs is illegal under international law (e.g., WHO regulations and Biological Weapons Convention). |

| Public Statements | Neither Bill Gates nor his foundation has ever claimed or been proven to own smallpox spores. |

| Source of Misinformation | False claims often stem from misinterpreted statements, funding of vaccine research, or baseless conspiracy theories. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Gates Foundation and Biodefense Funding

The Bill & Gates Foundation has allocated over $1.5 billion to biodefense initiatives since 2015, focusing on pandemic preparedness, vaccine development, and global health security. This funding includes partnerships with organizations like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which aims to accelerate vaccine development for emerging infectious diseases. While the foundation’s investments are publicly documented, the nature of biodefense research often involves sensitive materials, such as smallpox virus samples, stored in high-security labs like the CDC’s in Atlanta and Russia’s VECTOR Institute. The foundation does not "own" smallpox spores but supports research to develop countermeasures, including vaccines and diagnostic tools, to mitigate potential bioterrorism threats or accidental releases.

Consider the logistical challenges of biodefense funding: allocating resources to research smallpox without proliferating its risks. The Gates Foundation’s approach emphasizes collaboration with international bodies like the World Health Organization (WHO) to ensure transparency and ethical standards. For instance, funding has enabled the development of third-generation smallpox vaccines, such as MVA-BN (approved in 2019), which are safer than older vaccines and suitable for immunocompromised individuals. These vaccines are stockpiled by governments for emergency use, not privately owned by the foundation or Bill Gates. Practical tip: Stay informed about your country’s biodefense strategies and advocate for equitable access to vaccines during public health emergencies.

A comparative analysis reveals that the Gates Foundation’s biodefense funding is part of a broader trend in philanthropic investment in global health security. Unlike government-led initiatives, philanthropic funding often prioritizes innovation and rapid response. For example, during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, the foundation’s $50 million commitment helped scale up diagnostic tools and treatment centers in West Africa. However, critics argue that such funding can overshadow underfunded public health systems in low-income countries. To address this, the foundation has increasingly focused on strengthening local healthcare infrastructure, ensuring that biodefense investments complement rather than replace foundational health services.

Persuasively, the foundation’s role in biodefense is not without controversy. Conspiracy theories, such as the false claim that Bill Gates owns smallpox spores, often stem from misinformation about vaccine research and global health initiatives. These theories undermine public trust in science and hinder efforts to prepare for future pandemics. To combat this, the foundation has invested in science communication and literacy programs, aiming to bridge the gap between experts and the public. Practical takeaway: Verify information from credible sources like the WHO or CDC, and engage in constructive dialogue to counter misinformation in your community.

Descriptively, the Gates Foundation’s biodefense funding is a multifaceted effort, blending scientific innovation with global collaboration. Imagine a network of labs, researchers, and policymakers working together to predict, prevent, and respond to biological threats. For instance, the foundation’s support for the Global Virome Project aims to identify 99% of unknown viruses in wildlife that could spill over to humans, reducing the risk of future pandemics. This proactive approach contrasts with reactive measures, such as stockpiling smallpox vaccines, which are necessary but insufficient without early detection systems. By investing in both prevention and response, the foundation aims to create a safer, more resilient world.

Mange Mites and Dog Aggression: Unraveling the Behavioral Connection

You may want to see also

Smallpox Eradication and Preservation Efforts

Smallpox, a disease that once ravaged populations, was officially declared eradicated in 1980 thanks to a global vaccination campaign led by the World Health Organization (WHO). This monumental achievement marked the first and only time a human disease has been completely eliminated through targeted public health efforts. The success hinged on the widespread administration of the smallpox vaccine, which contained live vaccinia virus, a close relative of the smallpox virus. A single dose provided immunity for 3 to 5 years, with a booster extending protection for up to 10 years. The vaccine’s effectiveness, combined with rigorous surveillance and containment strategies, ensured the virus’s extinction in the wild.

Despite its eradication, smallpox remains a topic of concern due to the preservation of the virus in two high-security laboratories: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology (VECTOR) in Russia. These repositories were initially justified for research purposes, such as developing better vaccines and antiviral treatments. However, the continued existence of smallpox spores raises ethical and security questions. Critics argue that any stockpile, no matter how secure, poses a risk of accidental release or misuse by malicious actors. Proponents counter that retaining samples is essential for preparedness, as the virus could theoretically re-emerge naturally or be weaponized.

The debate over smallpox preservation intersects with figures like Bill Gates, whose philanthropic efforts in global health have occasionally drawn scrutiny. While there is no evidence that Gates owns smallpox spores, his foundation has invested heavily in vaccine development and pandemic preparedness. This includes funding research on diseases with smallpox-like potential, such as monkeypox, and supporting initiatives to strengthen global health systems. Gates’ advocacy for vaccine equity and disease eradication aligns with the legacy of smallpox eradication, though his involvement in biotechnology and public health has sparked conspiracy theories, including unfounded claims about smallpox ownership.

For individuals interested in smallpox’s history and its implications today, understanding the eradication process offers valuable lessons. The campaign’s success relied on international cooperation, community engagement, and a clear scientific strategy. Modern efforts to combat diseases like polio and COVID-19 draw on these principles. Practically, individuals can contribute by staying informed about vaccine-preventable diseases, supporting global health initiatives, and advocating for equitable access to medical resources. While smallpox is no longer a threat, its story serves as a reminder of humanity’s capacity to overcome even the most devastating diseases through collective action.

Finally, the preservation of smallpox spores underscores the delicate balance between scientific progress and biosecurity. As technology advances, the potential for synthetic biology to recreate extinct pathogens grows, raising new challenges. Policymakers, scientists, and the public must engage in ongoing dialogue to ensure that research benefits humanity without endangering it. The smallpox eradication story is not just a triumph of the past but a blueprint for addressing future threats, emphasizing vigilance, collaboration, and ethical stewardship of scientific knowledge.

Buying Magic Mushroom Spores in Australia: Legalities and Options Explained

You may want to see also

Conspiracy Theories Linking Gates to Smallpox

Bill Gates, co-founder of Microsoft and philanthropist, has become a central figure in numerous conspiracy theories, particularly those surrounding global health initiatives. One such theory alleges that Gates owns smallpox spores, a claim that has gained traction despite its lack of evidence. This accusation often ties into broader narratives about population control, vaccine conspiracies, and the supposed hidden agendas of global elites. To dissect this theory, it’s essential to examine its origins, the role of misinformation, and the scientific realities of smallpox eradication.

The smallpox virus, officially eradicated in 1980, exists only in two high-security laboratories: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology (VECTOR) in Russia. These repositories are strictly regulated by the World Health Organization (WHO), with no private individuals, including Bill Gates, having access or ownership. Conspiracy theorists often ignore this fact, instead weaving narratives that Gates, through his funding of vaccine research and global health programs, is secretly stockpiling smallpox for nefarious purposes. This claim is not only baseless but also contradicts the transparent operations of international health organizations.

A key driver of this conspiracy is the misinterpretation of Gates’ involvement in pandemic preparedness. His foundation has funded research on vaccine development and disease modeling, including simulations of hypothetical smallpox outbreaks. These efforts aim to strengthen global health systems, not to weaponize pathogens. However, critics twist these initiatives, portraying them as evidence of a hidden agenda. For instance, a 2021 simulation by the Nuclear Threat Initiative, partially funded by the Gates Foundation, explored the response to a bioterrorism scenario involving smallpox. Conspiracy theorists misrepresented this exercise as proof of Gates’ involvement in creating or hoarding smallpox spores, despite its purely preparatory nature.

To counter such misinformation, it’s crucial to rely on verified sources and understand the historical context of smallpox eradication. The last known natural case occurred in 1977, and the virus’s containment is a testament to global cooperation. Anyone spreading claims about private ownership of smallpox spores should be challenged to provide credible evidence, which invariably does not exist. Practical steps to combat misinformation include fact-checking through reputable organizations like the WHO or CDC, educating oneself on the principles of virology, and critically evaluating the motives behind sensationalist claims.

In conclusion, the conspiracy theory linking Bill Gates to smallpox spores is a prime example of how misinformation can distort reality. By focusing on facts—such as the secure storage of smallpox and the transparent goals of global health initiatives—individuals can dismantle these narratives. The takeaway is clear: skepticism is healthy, but it must be grounded in evidence, not speculation.

Ammonia's Power: Can It Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$21.43 $22.99

$14.99 $14.95

Global Smallpox Sample Storage Locations

Smallpox, a disease eradicated in 1980, remains a topic of global concern due to the existence of stored virus samples. These samples are housed in two primary locations: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, USA, and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology (VECTOR) in Koltsovo, Russia. These repositories are sanctioned by the World Health Organization (WHO) and are subject to strict biosafety protocols to prevent accidental release or misuse. While conspiracy theories occasionally link figures like Bill Gates to smallpox spores, there is no credible evidence supporting such claims. The focus should instead be on understanding the legitimate storage, purpose, and risks associated with these remaining samples.

Analyzing the rationale behind retaining smallpox samples reveals a delicate balance between scientific progress and biosecurity. Researchers argue that these samples are essential for developing new vaccines, antiviral drugs, and diagnostic tests, particularly in the event of a bioterrorism threat. For instance, the 2003 SARS outbreak and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic underscored the need for rapid vaccine development, a process that could be expedited with access to live pathogens. However, critics contend that the risks of accidental release or theft outweigh the benefits, especially given advancements in synthetic biology that could recreate the virus without physical samples. This debate highlights the importance of transparent oversight and international cooperation in managing such dangerous materials.

For those interested in the technical aspects of smallpox storage, the facilities at the CDC and VECTOR are designed to meet Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4) standards, the highest level of biocontainment. This includes airtight laboratories, multiple layers of protective clothing for personnel, and HEPA-filtered air systems to prevent airborne contamination. Access is restricted to authorized personnel, and all activities are monitored by international bodies. Practical tips for understanding these measures include familiarizing oneself with BSL-4 protocols, which can be found in WHO guidelines, and following updates from organizations like the CDC to stay informed about global biosecurity efforts.

Comparing the storage locations reveals both similarities and differences in their approaches. While both the CDC and VECTOR adhere to BSL-4 standards, VECTOR’s facility is located in a remote area of Siberia, theoretically reducing the risk of unauthorized access. The CDC, on the other hand, benefits from its integration into a larger public health infrastructure, facilitating collaboration with other U.S. agencies. These distinctions underscore the importance of geographic and operational diversity in safeguarding global health. For individuals or organizations involved in biosecurity, studying these models can provide valuable insights into designing resilient containment systems.

In conclusion, the storage of smallpox samples is a critical yet contentious issue that demands informed public discourse. By focusing on the specifics of storage locations, biosafety protocols, and the ongoing debate over their necessity, we can move beyond misinformation and engage in constructive dialogue. Whether you are a researcher, policymaker, or concerned citizen, understanding these details is essential for contributing to the global effort to balance scientific advancement with security. Practical steps include advocating for transparency, supporting international oversight, and staying informed about developments in biosecurity technology.

Detergents vs. Bacterial Spores: Uncovering Their Impact and Resistance

You may want to see also

WHO Regulations on Smallpox Research and Ownership

The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains strict regulations on smallpox research and ownership, ensuring that the eradicated virus remains under secure control. These rules are designed to prevent accidental or intentional release, while allowing limited scientific study to advance medical preparedness. Under WHO guidelines, smallpox samples are stored in only two high-security labs globally: the CDC in Atlanta, USA, and VECTOR in Koltsovo, Russia. Any research involving live smallpox virus requires WHO approval, with stringent biosafety protocols to minimize risk.

For those considering smallpox research, the WHO mandates a detailed application process. Researchers must demonstrate the scientific necessity of their work, outline containment measures, and provide evidence of compliance with Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4) standards. This includes negative-pressure laboratories, full-body protective suits, and HEPA-filtered air systems. Notably, the WHO prohibits private ownership of smallpox spores, ensuring that all samples remain under the control of designated public health institutions. This prevents individuals, including high-profile figures like Bill Gates, from possessing the virus for personal or corporate use.

A critical aspect of WHO regulations is the oversight of smallpox sequencing and genetic research. While studying the virus’s genome is permitted, sharing or publishing full sequences requires WHO authorization to prevent misuse, such as synthetic recreation of the virus. This balance between scientific progress and security reflects the WHO’s dual mandate: to foster research that could lead to better vaccines or treatments, while safeguarding against bioterrorism or accidental release. Researchers must also adhere to the 1975 WHO Smallpox Eradication Program’s legacy, which emphasizes global collaboration and transparency.

In practice, these regulations mean that no individual, including Bill Gates, can legally own smallpox spores. Gates, through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, has funded vaccine research and global health initiatives, but such efforts operate within WHO frameworks. For instance, smallpox vaccine development involves using attenuated strains or closely related viruses like vaccinia, not live smallpox. This ensures compliance with international laws and ethical standards. For the public, understanding these regulations underscores the global commitment to preventing smallpox’s reemergence, while allowing controlled research to protect future generations.

Do Volvox Produce Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Their Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There is no credible evidence or official documentation to suggest that Bill Gates owns smallpox spores. Such claims are often part of misinformation campaigns.

These claims stem from conspiracy theories that falsely accuse Bill Gates of using vaccines or biological agents for nefarious purposes, despite a lack of evidence.

Smallpox spores are highly regulated and classified as a dangerous pathogen. Only authorized laboratories with strict biosafety measures are permitted to handle them.

Bill Gates, through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, supports global health initiatives, including disease eradication. However, there is no evidence of involvement in smallpox spore ownership or research.

Smallpox spores are officially stored in two high-security laboratories: one in the United States (CDC) and one in Russia (VECTOR Institute), under strict international oversight.