Macrocondia, a term often associated with certain fungal structures, raises questions about their cellular composition, particularly whether each cell within them contains spores. These structures, typically found in various fungi, play a crucial role in reproduction and dispersal. While macrocondia are known for their spore-bearing capabilities, the specific arrangement and function of cells within them vary among different fungal species. In some cases, individual cells within macrocondia may indeed contain spores, serving as the primary units for dispersal and colonization. However, not all cells in these structures are necessarily spore-bearing; some may have other functions, such as structural support or nutrient storage. Understanding the cellular organization of macrocondia is essential for comprehending fungal life cycles and their ecological roles. Thus, the question of whether each cell in macrocondia contains spores highlights the complexity and diversity of fungal reproductive strategies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Structure of Macrocondia: Examines the internal composition and organization of macrocondia, focusing on spore presence

- Spore Formation Process: Explores how spores develop within macrocondia, if applicable, and key mechanisms

- Types of Spores in Macrocondia: Identifies and classifies spore types found in macrocondia, if present

- Function of Spores in Macrocondia: Investigates the role and purpose of spores within macrocondia, if they exist

- Comparative Analysis with Other Structures: Compares macrocondia to similar structures to determine spore containment uniqueness

Structure of Macrocondia: Examines the internal composition and organization of macrocondia, focusing on spore presence

Macrocondia, a term often associated with fungal structures, presents a fascinating subject for exploration, particularly regarding its internal architecture and the role of spores. A critical question arises: Are spores uniformly distributed within each cell of macrocondia, or is their presence more nuanced? To address this, one must delve into the intricate organization of these structures, which are typically found in certain fungi and play a pivotal role in their reproductive strategies.

The Cellular Landscape of Macrocondia:

Imagine a microscopic city, where each building (cell) has a specific function. In the case of macrocondia, these cells are not uniform in their content. The internal composition varies, with some cells dedicated to structural support, while others are specialized for spore production. This differentiation is crucial for the organism's life cycle. For instance, in the fungus *Aspergillus*, macrocondia-like structures contain spore-bearing cells, known as conidiophores, which are distinct from the surrounding sterile cells. This segregation of functions challenges the notion that every cell within macrocondia contains spores.

Spore Distribution: A Strategic Approach

The presence of spores within macrocondia is not random but follows a strategic pattern. Spores, being the primary means of fungal reproduction, are often concentrated in specific areas to maximize dispersal efficiency. In many fungi, spores are produced at the tips of specialized cells, forming a structure akin to a microscopic fruit. This design ensures that spores are readily released into the environment, facilitating colonization of new habitats. For example, in the genus *Penicillium*, spores are borne on the ends of long, slender cells, creating a brush-like appearance, which aids in spore dispersal.

Analyzing Spore-Bearing Cells:

Not all cells within macrocondia are created equal when it comes to spore production. Spore-bearing cells, or sporogenous cells, undergo a unique developmental process. These cells typically contain multiple nuclei and are larger than their non-spore-bearing counterparts. During spore formation, these cells may divide repeatedly, producing numerous spores within a single cell before releasing them. This process is highly regulated, ensuring that spores are mature and viable upon release. For instance, in the fungus *Neurospora*, each spore-bearing cell can produce up to 32 spores, which are then dispersed through various mechanisms.

Practical Implications and Research Directions:

Understanding the internal structure of macrocondia and spore distribution has practical applications in various fields. In agriculture, knowing the spore-bearing cells' location can aid in developing targeted fungicides, minimizing damage to non-spore-producing cells. Additionally, in biotechnology, the study of spore formation within macrocondia can inspire the design of efficient bioreactors for spore production. Researchers can manipulate environmental conditions to optimize spore yield, potentially benefiting industries such as food production and pharmaceuticals. For instance, controlling humidity and nutrient availability can significantly impact spore development, offering a practical approach to enhancing fungal cultivation.

In summary, the structure of macrocondia reveals a sophisticated organization where spore presence is not ubiquitous but strategically localized. This knowledge not only satisfies scientific curiosity but also has tangible applications, from agriculture to biotechnology, highlighting the importance of understanding fungal microarchitecture.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Illegal in Ohio? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Process: Explores how spores develop within macrocondia, if applicable, and key mechanisms

Macrocondia, often associated with fungal structures, are large, multicellular bodies that play a crucial role in the life cycle of certain fungi. The question of whether each cell within macrocondia contains spores is central to understanding their function and reproductive strategy. In many fungal species, macrocondia serve as spore-bearing structures, but the distribution and development of spores within these structures vary significantly. For instance, in some basidiomycetes, spores are produced externally on specialized cells called basidia, while in others, spores may develop internally within the macrocondia tissue. This variation highlights the complexity of spore formation processes and the need to examine specific mechanisms at play.

The spore formation process within macrocondia begins with the differentiation of specialized cells, often triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient availability or changes in light. In fungi like *Aspergillus*, macrocondia (or conidiophores) produce spores through a process called conidiogenesis, where chains of spores (conidia) are formed at the tips of the structure. Each spore develops from a single cell, which undergoes a series of divisions and maturations. Notably, not every cell in the macrocondia becomes a spore; some cells remain structural, providing support and protection. This selective sporulation ensures efficient dispersal while maintaining the integrity of the macrocondia.

A key mechanism in spore formation is the regulation of gene expression, which controls cell differentiation and sporulation. For example, in *Neurospora crassa*, the *brlA* gene acts as a master regulator, initiating the development of spore-forming cells. Environmental factors, such as pH and temperature, can influence this process, affecting spore yield and viability. Practical applications of this knowledge include optimizing conditions for fungal cultivation in biotechnology, where precise control of sporulation can enhance the production of enzymes or bioactive compounds. For instance, maintaining a pH of 5.5–6.0 and a temperature of 25–30°C can promote efficient spore formation in many fungal species.

Comparatively, in zygomycetes, macrocondia (or sporangia) produce spores through a different mechanism. Here, spores develop within a single, large cell through multiple rounds of nuclear division without cytoplasmic division, a process known as cleistothecial development. This contrasts with the individual cell differentiation seen in ascomycetes and basidiomycetes. Understanding these differences is critical for identifying fungal species and predicting their ecological roles, such as in decomposition or pathogen transmission. For example, recognizing the spore-bearing structures of *Rhizopus* can aid in diagnosing mucormycosis, a severe fungal infection.

In conclusion, while not every cell in macrocondia contains spores, the spore formation process is a highly regulated and specialized mechanism. From gene expression to environmental influences, multiple factors determine which cells develop into spores and how they are released. This knowledge not only advances our understanding of fungal biology but also has practical implications for agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. By studying these processes, researchers can develop strategies to control fungal growth, enhance spore production, and mitigate fungal diseases, ultimately leveraging the unique capabilities of macrocondia in various applications.

Are Spores Servers Down? Troubleshooting Tips and Status Updates

You may want to see also

Types of Spores in Macrocondia: Identifies and classifies spore types found in macrocondia, if present

Macrocondia, a term often associated with certain fungal structures, raises questions about the presence and types of spores within its cells. While not all cells in macrocondia contain spores, those that do play a crucial role in the organism's life cycle. Spores in macrocondia are typically classified into two main types: asexual spores and sexual spores. Asexual spores, such as conidia, are produced through mitosis and serve as a rapid means of reproduction. Sexual spores, like zygospores or ascospores, result from meiosis and genetic recombination, ensuring genetic diversity. Understanding these spore types is essential for identifying and studying macrocondia in various ecological and laboratory contexts.

To identify spore types in macrocondia, begin by examining the structure under a microscope at 400x magnification. Asexual spores often appear as single-celled, dry, and easily dispersed structures, while sexual spores are typically thicker-walled and more resilient. For instance, conidia are usually smooth and oval-shaped, whereas ascospores are often enclosed in sac-like structures called asci. Practical tip: Use a lactophenol cotton blue stain to enhance spore visibility and differentiate between types. This method is particularly useful for researchers and mycologists working with fungal cultures or field samples.

A comparative analysis of spore types reveals their distinct functions and adaptations. Asexual spores are ideal for colonizing new environments quickly due to their lightweight and prolific production. In contrast, sexual spores are better suited for long-term survival in harsh conditions, such as drought or extreme temperatures. For example, zygospores can remain dormant for years before germinating under favorable conditions. This duality highlights the evolutionary strategies of macrocondia to thrive in diverse habitats. When studying these spores, consider the environmental factors that may influence their development and dispersal.

Classifying spores in macrocondia requires a systematic approach. Start by documenting the morphology, size, and arrangement of spores. For asexual spores, note their mode of dispersal (e.g., wind, water, or insects). For sexual spores, identify the reproductive structures involved in their formation. Caution: Avoid confusing macrocondia with similar fungal structures like microcondia, which may contain different spore types. A useful takeaway is to maintain a spore reference chart for quick identification. This guide should include images, measurements, and key characteristics of each spore type, ensuring accuracy in classification.

In practical applications, understanding spore types in macrocondia is vital for fields like agriculture, medicine, and ecology. For instance, identifying pathogenic spore types can aid in disease management, while recognizing beneficial spores can support biocontrol efforts. Dosage values for spore application in agricultural settings vary; for example, conidial suspensions are often applied at concentrations of 10^6 to 10^8 spores per milliliter for effective pest control. Age categories of spores (e.g., mature vs. immature) also influence their viability and function. By mastering spore identification and classification, researchers and practitioners can harness the potential of macrocondia for various applications.

Can Tinea Pedis Spores Survive Freezing Temperatures? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Function of Spores in Macrocondia: Investigates the role and purpose of spores within macrocondia, if they exist

Macrocondia, a term often associated with certain fungal structures, raises questions about the presence and function of spores within its cellular composition. Spores, in the fungal kingdom, are typically reproductive units designed for dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. However, the specific role of spores within macrocondia remains a subject of investigation. To understand this, one must first clarify whether macrocondia inherently contains spores or if their presence is conditional. This distinction is crucial, as it influences how we interpret the biological function and ecological significance of these structures.

Analyzing the structure of macrocondia reveals that not all cells within it necessarily contain spores. Macrocondia, often found in certain basidiomycetes, serves as a supportive tissue rather than a primary reproductive organ. Spores, when present, are typically localized in specific regions such as the hymenium, where they are produced and released. This spatial segregation suggests that the primary function of macrocondia is structural—providing stability and form to the fruiting body—rather than reproductive. Thus, while spores may exist within macrocondia, they are not uniformly distributed across all cells, highlighting a functional specialization within the organism.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the role of spores in macrocondia has implications for fungal cultivation and conservation. For instance, in mushroom farming, knowing where spores are located within the macrocondia can optimize harvesting techniques. Farmers can focus on spore-bearing regions to ensure successful propagation. Similarly, in ecological studies, identifying spore-containing cells aids in assessing fungal dispersal mechanisms and their contribution to biodiversity. This knowledge is particularly valuable for species with limited or threatened habitats, where spore viability becomes critical for survival.

Comparatively, the function of spores in macrocondia contrasts with their role in other fungal structures like asci or sporangia, where spores are the primary focus. In macrocondia, spores serve a secondary purpose, complementing the structure’s main function. This distinction underscores the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies and the adaptability of spores as survival units. For example, while spores in asci are encased for protection, those in macrocondia may be more exposed, prioritizing dispersal over longevity. Such differences highlight the evolutionary trade-offs fungi make in spore production and distribution.

In conclusion, the function of spores within macrocondia is nuanced, reflecting a balance between structural support and reproductive potential. While not every cell contains spores, their presence in specific regions underscores their role in dispersal and survival. This understanding is essential for both scientific research and practical applications, from agriculture to conservation. By investigating the unique role of spores in macrocondia, we gain deeper insights into fungal biology and its broader ecological impact.

Where to Buy Milky Spore: Top Retailers and Online Sources

You may want to see also

Comparative Analysis with Other Structures: Compares macrocondia to similar structures to determine spore containment uniqueness

Macrocondia, often associated with certain fungi, are large, multicellular structures that play a role in spore production and dispersal. To assess whether each cell within macrocondia contains spores, a comparative analysis with similar fungal structures—such as sporangia, asci, and basidia—provides clarity. Sporangia, found in molds like *Rhizopus*, are sac-like structures where spores develop internally, with each sporangium containing numerous spores. In contrast, asci (in sac fungi like *Saccharomyces*) and basidia (in mushrooms like *Agaricus*) are specialized cells that externally bear spores, typically in groups of eight. Macrocondia, however, are distinct in their multicellular composition, raising questions about spore distribution within their cells.

Analyzing these structures reveals that spore containment is not uniform across fungal groups. While sporangia and asci concentrate spores in specific compartments, macrocondia’s larger, more complex architecture suggests a different mechanism. For instance, in *Aspergillus*, spores are produced on conidiophores, not within individual cells, whereas macrocondia may integrate spores within their tissue or on external surfaces. This comparison highlights that macrocondia’s spore containment is likely unique, neither confined to single cells nor exclusively external, but potentially distributed across the structure.

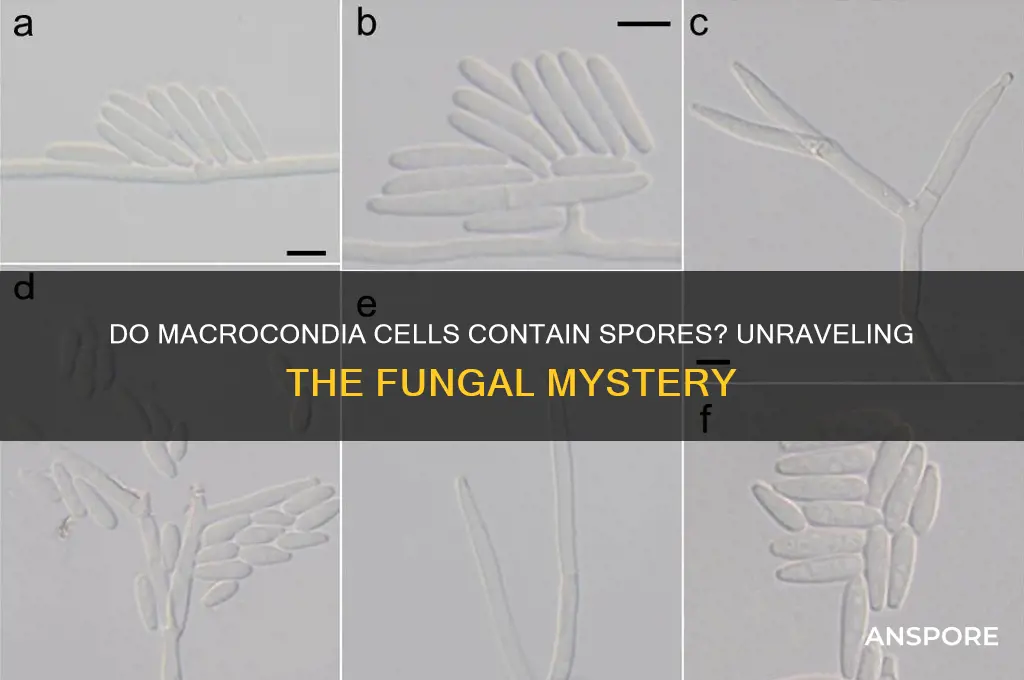

To determine spore presence in macrocondia cells, practical steps include microscopic examination at 400x–1000x magnification, staining with lactophenol cotton blue for contrast, and comparing mature vs. immature structures. For example, in *Xylaria*, macrocondia release spores through surface openings, suggesting spores are not contained within individual cells but are part of a collective dispersal system. This contrasts with basidia, where each cell directly supports spore development. Researchers should avoid assuming uniformity across fungal structures and instead focus on macrocondia’s specific developmental stages and environmental triggers for spore formation.

Persuasively, macrocondia’s spore containment uniqueness lies in their hybrid approach—combining internal tissue involvement with external release mechanisms. Unlike the singular function of asci or basidia, macrocondia’s multicellular nature allows for both protection and efficient dispersal. This adaptability may explain their prevalence in diverse fungal species, from wood-decaying fungi to soil dwellers. Understanding this distinction is crucial for applications in mycology, such as optimizing spore collection for biotechnology or controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture.

In conclusion, while sporangia, asci, and basidia offer clear examples of spore containment, macrocondia defy categorization. Their structure suggests spores are not confined to individual cells but are integrated into a larger, coordinated system. This comparative analysis underscores the need for tailored research methods when studying macrocondia, ensuring accurate identification and utilization of their spore-bearing capabilities. Practical tips include documenting developmental stages, using species-specific stains, and correlating environmental factors with spore production for comprehensive insights.

Growing Mushrooms from Spores: A Beginner's Guide to Cultivation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, macroconidia are asexual spores themselves, not cells containing spores.

Macroconidia are individual spores, not structures that contain other spores.

No, macroconidia are terminal structures and do not produce additional spores within them.

The primary function of macroconidia is to serve as asexual reproductive units for fungi, dispersing to form new colonies.

Yes, structures like sporangia contain spores, but macroconidia are spores themselves and do not contain other spores.