The question of whether ETEC (Enterotoxigenic *Escherichia coli*) produces spores is a critical one, as it directly impacts our understanding of its survival, transmission, and control. ETEC is a pathogenic strain of *E. coli* primarily known for causing traveler’s diarrhea and is a leading cause of morbidity in developing countries, particularly among children. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium difficile* or *Bacillus anthracis*, ETEC does not produce spores. Instead, it relies on its ability to colonize the small intestine and secrete enterotoxins to cause disease. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions, but ETEC’s lack of spore formation means it is more susceptible to environmental stressors, such as desiccation, heat, and disinfectants. This characteristic influences its transmission dynamics, as it typically requires a viable bacterial cell to cause infection, often through contaminated food or water. Understanding ETEC’s non-spore-forming nature is essential for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies, such as vaccines and improved sanitation practices.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Etec spore formation mechanisms

Enterotoxigenic *Escherichia coli* (ETEC) is a significant cause of diarrhea, particularly in travelers and young children in low-resource settings. Despite its clinical importance, ETEC is not known to produce spores under natural conditions. This distinction is critical, as spore formation is a survival mechanism employed by certain bacteria, such as *Clostridium difficile* and *Bacillus anthracis*, to withstand harsh environments. ETEC, however, relies on other strategies for persistence, raising questions about the mechanisms that might govern spore formation if it were to occur. While no evidence supports ETEC sporulation, exploring hypothetical mechanisms can deepen our understanding of bacterial adaptation and resilience.

Analyzing the genetic and environmental factors that could theoretically trigger spore formation in ETEC reveals a complex interplay. Sporulation in bacteria typically requires a specific set of genes, such as those in the *spo* operon found in *Bacillus* species. ETEC lacks these genes, but its genome contains stress response pathways that could, in theory, be co-opted for spore-like structures under extreme conditions. For instance, the RpoS regulon, which governs stress resistance in *E. coli*, might play a role in forming protective capsules or dormant states resembling spores. However, such mechanisms remain speculative and unsupported by current research.

From an instructive perspective, understanding ETEC's survival strategies without sporulation highlights its reliance on biofilm formation and persistence in the gastrointestinal tract. Biofilms provide a protective matrix that shields ETEC from antibiotics and host defenses, allowing it to thrive in adverse conditions. Unlike spores, which are dormant and highly resistant, biofilms enable ETEC to remain metabolically active, facilitating continued toxin production and infection. Clinicians and researchers should focus on disrupting biofilms rather than targeting non-existent spores to combat ETEC effectively.

Comparatively, the absence of spore formation in ETEC contrasts sharply with spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum*, which pose risks due to their ability to survive extreme conditions. This difference influences treatment approaches; while spore-formers require high-temperature sterilization or specific antimicrobials, ETEC infections are often managed with hydration and, in severe cases, antibiotics like ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily for adults) or azithromycin (1 g as a single dose). Understanding these distinctions ensures appropriate therapeutic strategies and prevents misuse of resources targeting non-existent spore mechanisms.

In conclusion, while ETEC does not produce spores, exploring hypothetical spore formation mechanisms underscores its unique survival strategies. Focusing on biofilm disruption and targeted antimicrobial therapy remains the most effective approach to managing ETEC infections. This knowledge not only clarifies misconceptions but also guides practical interventions in clinical and public health settings.

Can Mold Spores Attach to Organs? Uncovering the Hidden Health Risks

You may want to see also

Conditions for etec sporulation

Enterotoxigenic *Escherichia coli* (ETEC) is a major cause of diarrhea in travelers and young children in low-resource settings, yet its ability to form spores remains a point of scientific inquiry. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium difficile*, ETEC is not traditionally classified as a sporulator. However, recent studies suggest that under specific stress conditions, ETEC may exhibit spore-like characteristics or dormant states, raising questions about the conditions required for such transformations. Understanding these conditions is critical for both clinical management and public health interventions.

To explore the potential for ETEC sporulation, consider the environmental stressors that typically induce spore formation in other bacteria. Nutrient deprivation, particularly the absence of carbon and nitrogen sources, is a key trigger. For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, starvation initiates a signaling cascade leading to spore formation. While ETEC lacks the genetic machinery for true sporulation, it may enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state under similar conditions. Experimental setups could involve culturing ETEC in minimal media with progressively reduced nutrient concentrations, monitoring cell viability and morphological changes over time.

Temperature and pH shifts also play a role in bacterial stress responses. ETEC, being a gastrointestinal pathogen, is adapted to the human gut's warm, neutral pH environment. Exposing ETEC to temperatures below 20°C or acidic pH levels (e.g., pH 4.5) could mimic the stress of transitioning from the gut to the external environment. Such conditions might force ETEC into a dormant state, potentially enhancing its survival outside a host. Researchers could employ time-lapse microscopy to observe cellular changes under these conditions, looking for indicators of dormancy such as reduced metabolic activity or altered cell wall composition.

Another critical factor is the presence of antimicrobial agents or host immune responses. ETEC encounters bile salts, antimicrobial peptides, and other defenses in the gut. Simulating these conditions in vitro—for example, by adding sub-lethal concentrations of bile salts (0.5–1%) or polymyxin B (10–50 μg/mL)—could reveal whether ETEC adopts protective mechanisms akin to sporulation. Such experiments would provide insights into how ETEC persists in hostile environments, informing strategies to disrupt its survival.

In practical terms, understanding these conditions has implications for water treatment and food safety. If ETEC can enter a spore-like state, conventional disinfection methods (e.g., chlorination) might be insufficient to eliminate it. Enhanced filtration or UV treatment could be necessary to ensure water safety in endemic regions. For travelers, this knowledge underscores the importance of rigorous hygiene practices, such as boiling water or using advanced filtration systems, to mitigate the risk of ETEC infection. While ETEC may not produce true spores, its ability to adapt to stress conditions warrants further investigation to combat its global health impact.

Can Mold Spores Hurt You? Understanding Health Risks and Prevention

You may want to see also

Etec spore detection methods

Enterotoxigenic *Escherichia coli* (ETEC) is a significant cause of diarrhea, particularly in travelers and young children in low-resource settings. While ETEC is primarily known for its ability to produce enterotoxins, the question of whether it forms spores remains a point of scientific inquiry. Spores, if present, would enhance ETEC’s survival in harsh environments, complicating detection and control. However, current evidence suggests ETEC does not produce spores under normal conditions. Despite this, detecting spore-like structures or dormant forms in ETEC remains a critical area of research, especially in developing robust diagnostic methods.

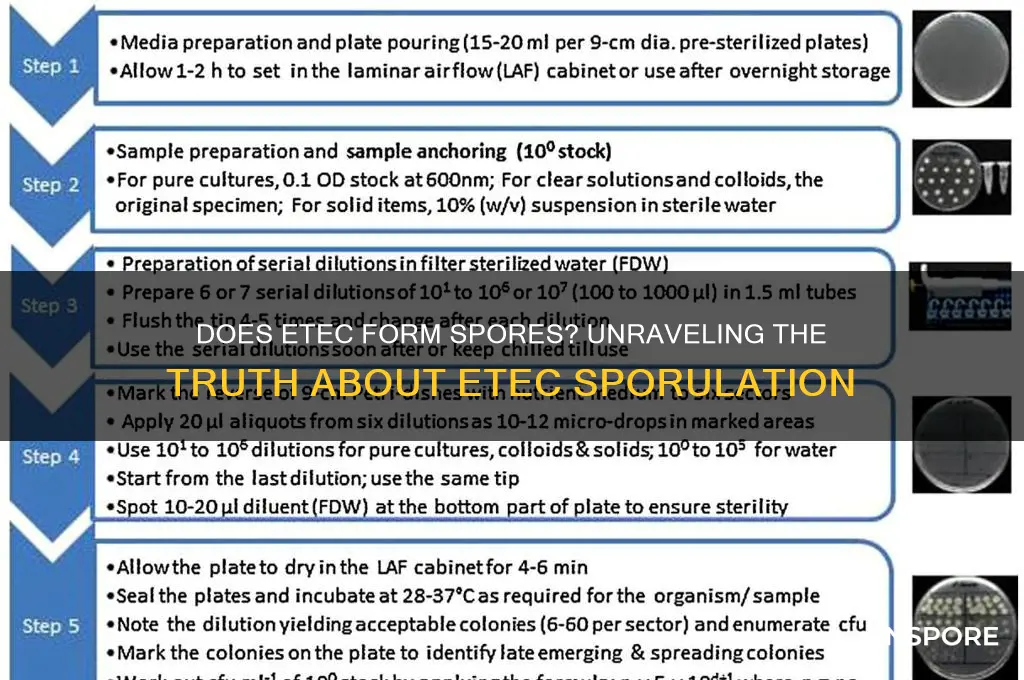

One of the primary methods for detecting spore-like structures in ETEC involves microscopic examination combined with staining techniques. Spores typically stain with dyes like malachite green or safranin due to their impermeable outer layer. Researchers may heat-treat ETEC samples to simulate stress conditions, then apply these stains to identify any spore-like formations. While this method is straightforward, its effectiveness is limited by the absence of true sporulation in ETEC. False positives can occur if other spore-forming bacteria are present in the sample, necessitating careful sample preparation and control measures.

Molecular techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), offer a more precise approach to detecting spore-related genes or dormant states in ETEC. Primers targeting sporulation-associated genes (e.g., *spo0A* or *sigE*) can be used to amplify DNA sequences, even if ETEC does not naturally sporulate. This method is highly sensitive and specific, making it ideal for research settings. However, its practical application in clinical or field settings is limited by the need for specialized equipment and expertise. For instance, a PCR assay with a detection limit of 10^3 CFU/mL could identify low levels of dormant or stress-resistant ETEC cells, but interpreting results requires understanding the biological relevance of such findings.

Flow cytometry is another advanced tool for detecting ETEC cells in dormant or spore-like states. By labeling cells with fluorescent dyes that bind to DNA or membrane integrity markers, researchers can differentiate between active and dormant populations. For example, propidium iodide can identify cells with compromised membranes, while DAPI stains all DNA, allowing for quantification of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells. This method provides real-time data and is particularly useful for studying ETEC’s response to environmental stressors. However, it requires expensive equipment and skilled operators, limiting its accessibility in resource-constrained settings.

In practical terms, enrichment cultures can be employed to detect dormant or stress-resistant ETEC cells. By culturing samples in selective media (e.g., MacConkey agar with added stressors like high salt or low pH), researchers can encourage the growth of cells that might otherwise remain undetected. For instance, a 24-hour enrichment in LB broth supplemented with 5% NaCl could revive subpopulations of ETEC that exhibit spore-like resilience. While this method is cost-effective and widely applicable, it lacks specificity and may not distinguish between true spores and stress-tolerant cells.

In conclusion, while ETEC does not produce spores, detecting spore-like or dormant states remains crucial for understanding its survival mechanisms. Methods ranging from microscopic staining to molecular and cytometric techniques offer varying levels of precision and practicality. Each approach has its strengths and limitations, and the choice of method depends on the specific research or diagnostic goals. As ETEC continues to pose a public health challenge, refining these detection methods will be essential for improving surveillance and control strategies.

Do Plants Produce Spores? Exploring the Plant Kingdom's Reproductive Methods

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of spores in etec survival

Enterotoxigenic *Escherichia coli* (ETEC) is a leading cause of diarrhea in travelers and young children in low-resource settings, yet its survival strategies remain a subject of scrutiny. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium difficile* or *Bacillus anthracis*, ETEC does not produce spores. This distinction is critical, as spores are resilient structures that enable bacteria to withstand harsh conditions like desiccation, heat, and antimicrobials. Without this mechanism, ETEC relies on alternative strategies to persist in environments outside the host, raising questions about its survival limitations and vulnerabilities.

To compensate for its inability to form spores, ETEC employs biofilm formation as a key survival tactic. Biofilms are microbial communities encased in a self-produced protective matrix, which shields bacteria from environmental stressors and host defenses. For instance, ETEC can adhere to surfaces in water sources or food, forming biofilms that enhance its longevity. However, biofilms are less durable than spores, as they can be disrupted by mechanical forces or specific enzymes. This difference underscores the trade-off ETEC faces: while biofilms aid survival, they lack the extreme resilience spores provide.

Another survival strategy for ETEC involves its ability to enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state under stress. In this state, the bacteria reduce metabolic activity, becoming undetectable by standard culturing methods but retaining viability. Studies suggest ETEC can enter the VBNC state in response to nutrient deprivation or exposure to antimicrobials, potentially contributing to its persistence in water or food. However, the VBNC state is not as robust as sporulation, as it does not confer long-term survival in extreme conditions like high temperatures or prolonged desiccation.

Understanding ETEC’s lack of spore production has practical implications for prevention and control. Unlike spore-forming pathogens, which require extreme measures like autoclaving for eradication, ETEC can be effectively eliminated by standard disinfection methods such as chlorination or boiling water. For travelers, this means ensuring water is treated or bottled, while in healthcare settings, routine sanitation practices suffice to reduce transmission. Additionally, targeting biofilm formation through antimicrobial peptides or enzymes could offer novel strategies to combat ETEC persistence in environmental reservoirs.

In summary, while ETEC does not produce spores, its survival hinges on biofilm formation and the VBNC state. These mechanisms, though less durable than sporulation, enable ETEC to persist in specific environments. By focusing on these vulnerabilities, public health interventions can effectively mitigate ETEC transmission, particularly in high-risk settings. This knowledge highlights the importance of tailored strategies in combating pathogens based on their unique survival adaptations.

Can You Purchase Spore on Origin? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Comparing etec to spore-forming bacteria

ETEC, or enterotoxigenic *Escherichia coli*, is a leading cause of traveler’s diarrhea, responsible for millions of cases annually, particularly in developing regions. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium difficile* or *Bacillus cereus*, ETEC does not produce spores. This distinction is critical for understanding its survival, transmission, and control. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to endure harsh conditions like heat, desiccation, and disinfectants, whereas ETEC relies on its vegetative form, which is more susceptible to environmental stressors. This vulnerability limits ETEC’s persistence outside the host but also means it requires specific conditions—such as contaminated food or water—to spread effectively.

To compare, spore-forming bacteria like *C. difficile* can survive on hospital surfaces for months, posing a persistent infection risk, especially in healthcare settings. ETEC, in contrast, typically causes acute, self-limiting illness and is less likely to establish long-term environmental reservoirs. For travelers, this means ETEC transmission is largely preventable through measures like drinking bottled water, avoiding raw foods, and practicing good hygiene. However, spore-forming pathogens require more stringent disinfection protocols, such as using spore-specific agents like chlorine bleach, to eliminate their resilient spores.

From a treatment perspective, ETEC infections are often managed with oral rehydration solutions and, in severe cases, antibiotics like ciprofloxacin or azithromycin. Spore-forming infections, such as *C. difficile*, may necessitate targeted therapies like fidaxomicin or fecal microbiota transplantation due to their ability to recur after spore germination. Understanding these differences is crucial for healthcare providers, as misidentifying the pathogen could lead to inappropriate treatment—for instance, using antibiotics that disrupt gut flora, potentially triggering spore germination in *C. difficile*.

Practically, travelers can reduce ETEC risk by carrying water purification tablets (e.g., iodine or chlorine-based) and avoiding ice cubes or unpeeled fruits in high-risk areas. For spore-forming bacteria, especially in healthcare or food handling, surfaces should be cleaned with 10% bleach solutions, and hands washed with soap for at least 20 seconds to disrupt spore-contaminated environments. While ETEC’s non-spore-forming nature limits its environmental resilience, spore-forming bacteria demand proactive, spore-specific interventions to prevent outbreaks.

In summary, comparing ETEC to spore-forming bacteria highlights the importance of tailoring prevention and treatment strategies to the pathogen’s biology. ETEC’s reliance on vegetative cells makes it more immediate but less enduring, while spore-formers pose a latent, persistent threat. Recognizing these differences empowers individuals and healthcare systems to respond effectively, whether through simple hygiene measures or rigorous disinfection protocols.

Can Disinfectants Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Enterotoxigenic *Escherichia coli* (ETEC) does not produce spores. It is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

ETEC survives outside the host by forming biofilms or persisting in contaminated environments, such as water or food, without the need for spore formation.

No, *E. coli* strains, including ETEC, are not known to produce spores. Sporulation is a characteristic of other bacterial genera, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*.

Knowing that ETEC does not produce spores simplifies treatment and prevention strategies, as it eliminates the need to target spore-specific mechanisms. Focus can instead be placed on hygiene, hydration, and antibiotics if necessary.

![Shirayuri Koji [Aspergillus oryzae] Spores Gluten-Free Vegan - 10g/0.35oz](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61ntibcT8gL._AC_UL320_.jpg)