Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, primarily through decomposition and nutrient cycling. Unlike plants, which reproduce via pollen, fungi have evolved a different reproductive strategy. Instead of pollen, fungi produce spores, which are microscopic, single-celled structures designed for dispersal and survival in various environments. These spores can be asexual (e.g., conidia) or sexual (e.g., basidiospores or asci), depending on the fungal species and its life cycle. Understanding the distinction between pollen and spores is essential, as it highlights the unique reproductive mechanisms of fungi and their adaptation to diverse habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproductive Structures | Fungi produce spores, not pollen. |

| Type of Spores | Asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores). |

| Function of Spores | Dispersal, survival in harsh conditions, and reproduction. |

| Size of Spores | Typically smaller than pollen grains, ranging from 1 to 100 micrometers. |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, insects, and other animals. |

| Pollen Production | Fungi do not produce pollen; pollen is exclusive to plants (spermatophytes). |

| Allergenicity | Some fungal spores can cause allergies, similar to pollen, but they are not pollen. |

| Ecological Role | Spores play a key role in fungal life cycles and ecosystem functions, such as decomposition and nutrient cycling. |

| Visibility | Spores are often invisible to the naked eye, unlike pollen grains, which can sometimes be seen as a fine dust. |

| Genetic Material | Spores contain genetic material for the next generation of fungi, similar to how pollen carries genetic material in plants. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fungi Reproduction Methods: Fungi reproduce via spores, not pollen, unlike plants

- Spores vs. Pollen: Spores are fungal reproductive units; pollen is plant-specific

- Fungal Spores Types: Fungi produce spores like conidia, zygospores, and basidiospores

- Pollen Function: Pollen aids plant fertilization; fungi lack this process

- Fungal Dispersal: Spores spread via air, water, or animals for fungal colonization

Fungi Reproduction Methods: Fungi reproduce via spores, not pollen, unlike plants

Fungi, unlike plants, do not produce pollen for reproduction. Instead, they rely on spores, which are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures designed for dispersal and survival in various environments. This fundamental difference highlights the unique reproductive strategies of fungi, which have evolved to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from forest floors to human habitats. Spores are produced in vast quantities, ensuring that even in unfavorable conditions, some will find suitable environments to germinate and grow.

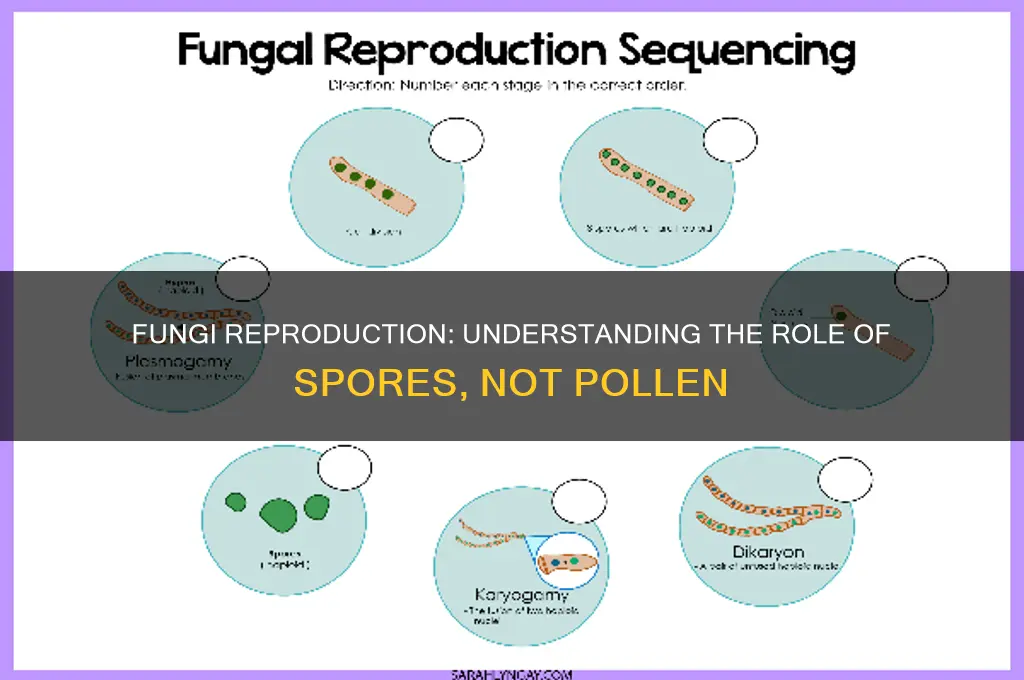

Analyzing the spore production process reveals its efficiency and adaptability. Fungi generate spores through asexual (mitosis) or sexual (meiosis) reproduction, depending on the species and environmental cues. For instance, molds like *Aspergillus* produce asexual spores called conidia, which are dispersed through air currents. In contrast, mushrooms release sexual spores, such as basidiospores, from gills or pores. This diversity in spore types and dispersal mechanisms allows fungi to colonize new areas rapidly, outpacing many other organisms in their ability to spread.

To understand the practical implications of fungal spores, consider their role in everyday life. For example, baker’s yeast (*Saccharomyces cerevisiae*) reproduces asexually through budding, a form of spore-like propagation, to ferment dough. In agriculture, fungal spores like those of *Trichoderma* are used as bio-control agents to combat plant pathogens. However, spores can also pose risks, such as triggering allergies (e.g., mold spores) or causing infections in immunocompromised individuals. Proper ventilation and humidity control are essential to manage indoor spore levels, reducing health risks.

Comparing fungal spores to plant pollen underscores their distinct functions. While pollen is a male gametophyte involved in sexual reproduction and requires a specific partner for fertilization, spores are self-sufficient units capable of developing into new fungal organisms independently. This independence allows fungi to reproduce in the absence of mates, a critical advantage in environments where other organisms are scarce. Additionally, spores’ resilience—some can survive extreme conditions like heat, cold, or desiccation—ensures fungal longevity, even in hostile habitats.

In conclusion, fungi’s reliance on spores rather than pollen is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By producing spores in vast numbers and with diverse dispersal methods, fungi ensure their survival and proliferation across ecosystems. Whether beneficial or detrimental, understanding spore biology is key to harnessing fungi’s potential in industries like food, medicine, and agriculture, while mitigating their negative impacts on health and infrastructure. This knowledge empowers us to coexist with fungi, leveraging their unique reproductive strategies for human benefit.

Exploring the Presence and Role of Spores in Animal Biology

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Pollen: Spores are fungal reproductive units; pollen is plant-specific

Fungi and plants both reproduce through tiny, often invisible particles, but these are fundamentally different in structure, function, and purpose. Fungi rely on spores, which are lightweight, single-celled reproductive units capable of surviving harsh conditions like drought or extreme temperatures. In contrast, plants produce pollen, which is multicellular, larger, and specifically designed for fertilization, often transported by wind, insects, or animals. This distinction is critical: spores are survivalists, while pollen is a delivery system for genetic material.

To understand the practical implications, consider how these particles affect humans. Fungal spores are ubiquitous in the environment and can trigger allergic reactions or respiratory issues, especially in individuals with asthma or compromised immune systems. For example, inhaling high concentrations of mold spores (a type of fungal spore) can lead to symptoms like sneezing, coughing, or skin irritation. Pollen, on the other hand, is the primary culprit behind seasonal allergies, with tree, grass, and weed pollen affecting millions annually. Monitoring spore and pollen counts in your area can help manage exposure; apps like Pollen.com or local weather forecasts often provide this data.

From a reproductive perspective, spores and pollen serve distinct roles. Fungal spores are dispersed through air, water, or animals and can germinate into new fungi under favorable conditions, often without needing a partner. This asexual reproduction allows fungi to colonize environments rapidly. Pollen, however, is part of a more complex sexual reproduction process in plants. It must travel from the male part (anther) to the female part (stigma) of a flower, typically relying on external agents like bees or wind. This dependency on pollinators highlights the specialized nature of pollen compared to the self-sufficient spore.

For gardeners or farmers, understanding these differences can inform better practices. Fungal spores thrive in damp, humid conditions, so reducing moisture through proper ventilation or fungicides can limit their spread. Pollen, however, is more about timing and environment—planting wind-pollinated crops (like corn) away from allergen-sensitive areas or choosing hybrid varieties with reduced pollen production can minimize impact. Additionally, wearing masks during high spore or pollen seasons can protect both workers and hobbyists.

In summary, while both spores and pollen are reproductive agents, their origins, structures, and functions are uniquely tailored to their respective organisms. Spores are fungi’s versatile survival tools, while pollen is plants’ specialized fertilization mechanism. Recognizing these differences not only clarifies biological processes but also empowers practical decisions in health, agriculture, and environmental management. Whether you’re battling allergies or cultivating crops, knowing your spores from your pollen is key.

Can Air Filters Effectively Trap and Prevent Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores Types: Fungi produce spores like conidia, zygospores, and basidiospores

Fungi, unlike plants, do not produce pollen. Instead, they rely on spores as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. These microscopic structures are lightweight, resilient, and capable of surviving harsh conditions, ensuring the fungus’s survival across diverse environments. Among the myriad types of fungal spores, three stand out for their distinct roles and structures: conidia, zygospores, and basidiospores. Each type reflects a unique reproductive strategy, tailored to the fungus’s ecological niche and life cycle.

Conidia are asexual spores produced at the tips or sides of specialized hyphae called conidiophores. They are among the most common fungal spores and are responsible for the rapid spread of many fungi, including those causing plant diseases like powdery mildew. For example, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* species release conidia into the air, where they can travel long distances before germinating under favorable conditions. Gardeners and farmers often combat conidia-producing fungi by reducing humidity and improving air circulation, as these spores thrive in damp environments. A practical tip: regularly prune overcrowded plants to enhance airflow and minimize spore buildup.

In contrast, zygospores are the product of sexual reproduction in certain fungi, such as those in the phylum Zygomycota. When two compatible hyphae fuse, they form a thick-walled zygospore that can withstand extreme conditions, including drought and temperature fluctuations. This dormancy ensures the fungus’s long-term survival, particularly in unpredictable habitats. For instance, the black bread mold *Rhizopus stolonifer* produces zygospores that can remain viable in soil for years. While zygospores are less frequently encountered than conidia, their resilience makes them crucial for fungal persistence in challenging ecosystems.

Basidiospores are the hallmark of the Basidiomycota phylum, which includes mushrooms, puffballs, and rust fungi. These spores develop on club-shaped structures called basidia, typically found on the gills or pores of mushroom caps. When mature, basidiospores are ejected into the air, often with remarkable force, to disperse over wide areas. For example, a single mushroom can release millions of basidiospores daily. This efficient dispersal mechanism explains why mushrooms appear so suddenly after rain. Foraging enthusiasts should note that while many basidiomycetes are edible, others are toxic, so proper identification is essential. A cautionary tip: always consult a field guide or expert before consuming wild mushrooms.

Understanding these spore types not only sheds light on fungal biology but also has practical implications. For instance, conidia’s airborne nature makes them a common allergen, affecting individuals with mold sensitivities. Zygospores’ durability highlights the challenge of eradicating certain fungi from soil or stored grains. Basidiospores’ role in mushroom formation underscores the importance of fungi in forest ecosystems as decomposers and symbionts. By recognizing these distinctions, we can better manage fungal interactions, whether in agriculture, medicine, or conservation. Each spore type is a testament to fungi’s adaptability, showcasing their evolutionary success in a world dominated by larger organisms.

Do Mold Spores Die When They Dry Out? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pollen Function: Pollen aids plant fertilization; fungi lack this process

Fungi and plants are both integral to ecosystems, yet their reproductive strategies differ fundamentally. Plants rely on pollen, a fine powdery substance produced by male flower parts, to facilitate fertilization. This process, known as pollination, involves the transfer of pollen grains from the anther to the stigma, enabling the union of male and female gametes. Without pollen, most flowering plants would be unable to reproduce, highlighting its critical role in plant survival and biodiversity.

In contrast, fungi lack pollen entirely. Instead, they reproduce via spores, microscopic structures that disperse through air, water, or soil. These spores germinate under favorable conditions, giving rise to new fungal organisms. Unlike pollen, which is specifically adapted for plant fertilization, spores serve as a means of asexual or sexual reproduction in fungi, allowing them to colonize new environments efficiently. This distinction underscores the divergent evolutionary paths of plants and fungi.

To illustrate, consider the lifecycle of a dandelion versus that of a mushroom. A dandelion produces pollen, which is carried by wind or insects to fertilize other dandelions, ultimately producing seeds. In contrast, a mushroom releases spores from its gills, which can travel vast distances to establish new fungal colonies. While both processes ensure species propagation, the mechanisms and structures involved are entirely distinct, reflecting the unique biology of each organism.

Understanding these differences has practical implications, particularly in agriculture and conservation. For instance, farmers rely on pollinators like bees to transfer pollen between crops, ensuring fruit and seed production. Conversely, managing fungal diseases in crops requires strategies to limit spore dispersal, such as fungicides or crop rotation. By recognizing the roles of pollen and spores, we can better support plant and fungal ecosystems, fostering balance and productivity in natural and agricultural settings.

In summary, while pollen is essential for plant fertilization, fungi bypass this process altogether, relying instead on spores for reproduction. This fundamental difference not only highlights the diversity of life but also informs practical approaches to managing plant and fungal populations. Whether in a garden, farm, or forest, awareness of these reproductive strategies empowers us to nurture ecosystems more effectively.

Can Spores Trigger Nausea? Exploring the Surprising Connection

You may want to see also

Fungal Dispersal: Spores spread via air, water, or animals for fungal colonization

Fungi, unlike plants, do not produce pollen. Instead, they rely on spores as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. These microscopic structures are lightweight, resilient, and produced in vast quantities, enabling fungi to colonize diverse environments. Spores are the fungal equivalent of seeds, but their dispersal methods are far more varied and adaptive. Understanding how spores spread—whether through air, water, or animals—sheds light on the remarkable strategies fungi employ to thrive and expand their territories.

Airborne dispersal is one of the most common methods fungi use to spread their spores. Fungi like molds and mushrooms release spores into the atmosphere, where they can travel vast distances carried by wind currents. For instance, a single mushroom cap can release billions of spores in a single day. These spores are often equipped with structures like wings or hydrophobic surfaces that enhance their aerodynamic properties. To observe this process, place a mature mushroom on a sheet of paper overnight; the spore print left behind will reveal the intricate patterns and sheer volume of spores released. This method allows fungi to colonize new habitats quickly, even across geographical barriers.

Water also plays a crucial role in fungal spore dispersal, particularly for aquatic and soil-dwelling fungi. Spores released into water bodies can be carried downstream, colonizing new areas along riverbanks or coastal regions. Some fungi, like those in the genus *Fusarium*, produce spores that are buoyant and can survive in water for extended periods. Gardeners and farmers should be aware that overwatering plants can inadvertently aid fungal spread, as spores in the soil are more likely to be mobilized and transported to healthy plants. To mitigate this, ensure proper drainage and avoid excessive irrigation, especially in humid conditions.

Animals, including humans, act as unwitting carriers of fungal spores, facilitating their dispersal across ecosystems. Spores can attach to fur, feathers, or clothing and be transported to new locations. For example, bats play a significant role in spreading spores of cave-dwelling fungi as they move between roosts. Even insects like flies and beetles can carry spores on their bodies, aiding in fungal colonization. To minimize the spread of unwanted fungi in indoor environments, regularly clean and vacuum areas prone to moisture, such as bathrooms and kitchens, as spores can easily attach to fabrics and surfaces.

In conclusion, fungal dispersal through spores is a multifaceted process that leverages air, water, and animals to ensure widespread colonization. Each method highlights the adaptability and resilience of fungi, enabling them to thrive in virtually every habitat on Earth. By understanding these mechanisms, we can better manage fungal growth in agricultural, domestic, and natural settings, while also appreciating the ecological roles fungi play in nutrient cycling and decomposition. Whether you’re a gardener, scientist, or simply curious about the natural world, recognizing how spores spread is key to coexisting with these ubiquitous organisms.

Can Mold Spores Enter Your Ears? Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, fungi do not produce pollen. Pollen is produced by plants, specifically by flowering plants (angiosperms) and cone-bearing plants (gymnosperms), as part of their reproductive process.

Fungi release spores as their reproductive units. Spores are tiny, lightweight cells that can disperse through air, water, or other means to colonize new environments.

While both spores and pollen are involved in reproduction, they serve different purposes. Pollen is used for sexual reproduction in plants, whereas fungal spores can be involved in both asexual and sexual reproduction, depending on the species.

Fungi disperse spores through various methods, including wind, water, insects, and even explosive mechanisms in some species. For example, mushrooms release spores from their gills when mature.

Yes, fungal spores can cause allergies in some individuals, similar to pollen. Mold spores, in particular, are a common allergen and can trigger symptoms like sneezing, itching, and respiratory issues.