Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, from decomposing organic matter to forming symbiotic relationships with plants. One of the most fascinating aspects of fungi is their reproductive strategies, which often involve the production of spores. Spores are microscopic, single-celled structures that serve as the primary means of reproduction and dispersal for many fungal species. Unlike plants and animals, fungi do not rely on seeds or offspring for reproduction; instead, they release vast quantities of spores into the environment, which can travel through air, water, or soil to colonize new habitats. This method allows fungi to thrive in a wide range of environments and ensures their survival even in challenging conditions. Understanding how fungi reproduce by spores not only sheds light on their life cycle but also highlights their adaptability and ecological significance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Fungi primarily reproduce through spores. |

| Types of Spores | Asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, insects, animals, and human activities. |

| Survival Strategy | Spores are highly resistant to harsh conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals). |

| Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions (e.g., moisture, nutrients, temperature). |

| Role in Life Cycle | Essential for propagation, dispersal, and survival of fungal species. |

| Asexual vs. Sexual Spores | Asexual spores allow rapid reproduction, while sexual spores increase genetic diversity. |

| Examples of Fungi | Molds, yeasts, mushrooms, and other fungal species. |

| Environmental Impact | Spores contribute to fungal ecosystems, decomposition, and nutrient cycling. |

| Human Relevance | Spores can cause allergies, infections, and food spoilage but are also used in biotechnology and medicine. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Fungal Spores: Fungi produce diverse spores like ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores for reproduction

- Sporulation Process: Fungi form spores through meiosis or mitosis, depending on their life cycle stage

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores spread via wind, water, animals, or explosive discharge to colonize new environments

- Survival Strategies: Spores are resilient, surviving harsh conditions like drought, heat, and chemicals for long periods

- Role in Life Cycle: Spores are key for fungal reproduction, germination, and genetic diversity in ecosystems

Types of Fungal Spores: Fungi produce diverse spores like ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores for reproduction

Fungi are masters of diversity, and their reproductive strategies reflect this. While spores are the cornerstone of fungal reproduction, not all spores are created equal. Fungi produce a dazzling array of spore types, each adapted to specific environments and dispersal methods. Understanding these spore types – ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores – unlocks a deeper appreciation for the fungal kingdom's ingenuity.

Ascospores, for instance, are the product of sexual reproduction in Ascomycetes, the largest fungal phylum. These spores develop within sac-like structures called asci, often visible to the naked eye in molds like Penicillium. Basidiospores, characteristic of Basidiomycetes (think mushrooms and shelf fungi), are borne on club-shaped structures called basidia. Each basidium typically produces four spores, which are then launched into the air, sometimes with remarkable force.

Conidia represent a different strategy altogether. These asexual spores are produced by simple budding or fragmentation on specialized structures called conidiophores. Think of them as fungal clones, genetically identical to the parent fungus. This rapid and efficient method allows fungi like Aspergillus and Fusarium to colonize new territories quickly. Zygospores, on the other hand, are the result of a sexual union between two compatible fungal hyphae. These thick-walled, highly resistant spores are formed within a zygosporangium and can survive harsh conditions, ensuring the fungus's long-term survival.

Imagine a battlefield of microscopic warriors, each armed with a unique weapon. Ascospores, with their protective asci, are like armored knights, ready to withstand the elements. Basidiospores, launched like tiny projectiles, are the archers of the fungal world. Conidia, the clones, represent a swarm of foot soldiers, overwhelming their enemies through sheer numbers. And zygospores, the dormant survivors, are the hidden reserves, waiting for the perfect moment to strike.

Understanding these spore types isn't just academic curiosity. It has practical implications. For example, knowing that conidia are responsible for the rapid spread of mold in damp environments can inform strategies for mold prevention. Recognizing the airborne nature of basidiospores can help explain allergic reactions to mushrooms. By deciphering the language of fungal spores, we gain valuable insights into the hidden world beneath our feet and within our homes, ultimately leading to better management of fungal interactions with our environment and health.

Can Spores Grant Bacteria Eternal Life? Unraveling Microbial Immortality

You may want to see also

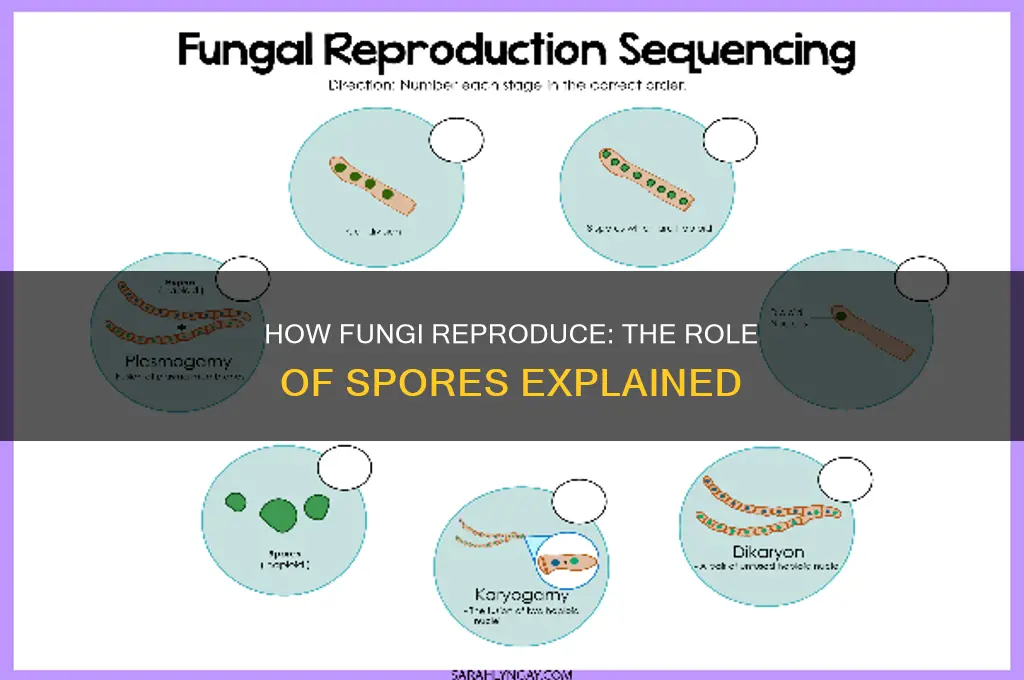

Sporulation Process: Fungi form spores through meiosis or mitosis, depending on their life cycle stage

Fungi, a diverse kingdom of organisms, employ a sophisticated strategy for survival and propagation: sporulation. This process is not a one-size-fits-all mechanism but rather a dynamic system tailored to the fungus’s life cycle stage. At its core, sporulation involves the formation of spores, which serve as both a means of reproduction and a survival structure. The method by which these spores are produced—meiosis or mitosis—hinges on whether the fungus is in its sexual or asexual phase, respectively. Understanding this distinction is crucial for anyone studying fungal biology or managing fungal populations in agriculture, medicine, or environmental contexts.

Consider the life cycle of a common fungus like *Aspergillus*. During its asexual phase, it produces spores called conidia through mitosis. These spores are genetically identical to the parent fungus and are rapidly dispersed to colonize new environments. This asexual reproduction is efficient for quick proliferation under favorable conditions. However, when environmental stresses like nutrient depletion or temperature changes occur, the fungus may enter its sexual phase. Here, meiosis takes center stage, producing genetically diverse spores such as asci or basidiospores. This diversity is a survival advantage, equipping offspring with varied traits to withstand unpredictable conditions.

The sporulation process is not merely a biological curiosity but has practical implications. For instance, in agriculture, understanding whether a fungal pathogen reproduces asexually or sexually can inform control strategies. Asexual spores, being genetically uniform, may be more susceptible to specific fungicides, while sexual spores’ genetic variability can complicate management. Similarly, in medical mycology, knowing the sporulation method of fungi like *Candida* or *Cryptococcus* aids in diagnosing and treating infections, as sexual spores can sometimes exhibit increased virulence or drug resistance.

To observe sporulation in action, one can conduct a simple experiment with baker’s yeast (*Saccharomyces cerevisiae*). In nutrient-rich media, yeast reproduces asexually through budding, a form of mitosis. However, under starvation conditions, it undergoes meiosis to form asci, each containing four haploid spores. This experiment not only illustrates the dual sporulation pathways but also highlights the environmental cues that trigger each process. For educators or hobbyists, this setup requires minimal equipment: agar plates, yeast cultures, and a microscope for spore observation.

In conclusion, the sporulation process in fungi is a masterclass in adaptability. By toggling between meiosis and mitosis, fungi ensure both rapid colonization and genetic diversity, depending on their needs. This mechanism underscores the resilience of fungi as a kingdom and their ability to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Whether you’re a researcher, farmer, or enthusiast, grasping the nuances of sporulation equips you with the knowledge to harness or counteract fungal behavior effectively.

Growing Morels from Spores: Unlocking the Mystery of Cultivation

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores spread via wind, water, animals, or explosive discharge to colonize new environments

Fungi have mastered the art of dispersal, employing a variety of mechanisms to ensure their spores reach new habitats. Wind dispersal, perhaps the most common method, relies on the lightweight nature of spores, which can travel vast distances when carried by air currents. For instance, the spores of *Aspergillus* fungi, measuring just 3-5 micrometers in diameter, can remain suspended in the air for hours, potentially colonizing environments far from their origin. This passive yet effective strategy highlights the adaptability of fungi in leveraging natural elements for survival.

Water serves as another critical medium for spore dispersal, particularly in aquatic and semi-aquatic environments. Fungi like *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, which causes chytridiomycosis in amphibians, release zoospores that swim through water using flagella before settling and germinating. In terrestrial settings, rain splash can dislodge spores from fungal structures, propelling them onto nearby plants or soil. Gardeners and farmers should note that excessive irrigation can inadvertently aid this process, spreading fungal pathogens like *Phytophthora* to healthy crops.

Animals, both large and small, play a surprising role in spore dispersal. Insects, such as flies and beetles, often carry spores on their bodies after visiting fungal fruiting bodies. For example, the spores of *Amanita* mushrooms adhere to the legs of ants, which then transport them to new locations. Larger animals, including mammals and birds, can disperse spores through their fur or feathers, or even via ingestion and excretion. A practical tip for mushroom foragers: avoid handling wild fungi with bare hands to prevent accidental spore transfer to unintended areas.

One of the most dramatic dispersal mechanisms is explosive discharge, employed by fungi like the cannonball fungus (*Sphaerobolus stellatus*). This species builds up pressure within its spore-containing structure until it bursts, launching spores up to 6 meters away. Similarly, the *Pilobolus* fungus uses a squirtgun-like mechanism to eject spores toward light sources, often landing on herbivores that then carry them elsewhere. While these methods are less common, they showcase the ingenuity of fungi in overcoming dispersal challenges.

Understanding these mechanisms is not just academically intriguing—it has practical implications. For instance, knowing that wind-dispersed spores can travel long distances underscores the importance of quarantining infected plants to prevent outbreaks. Similarly, recognizing the role of water in spore spread can inform irrigation practices in agriculture. By studying these dispersal strategies, we can better manage fungal populations, whether to control pathogens or cultivate beneficial species, ultimately fostering healthier ecosystems.

Are Spores Autotrophic or Heterotrophic? Unraveling Their Nutritional Secrets

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Strategies: Spores are resilient, surviving harsh conditions like drought, heat, and chemicals for long periods

Spores, the microscopic units of fungal reproduction, are nature’s ultimate survivalists. Encased in a protective cell wall, they can endure conditions that would destroy most life forms. Drought, extreme heat, and exposure to chemicals are no match for their resilience. This adaptability ensures fungi can persist in environments where other organisms cannot, from arid deserts to contaminated soils. Understanding this survival mechanism sheds light on why fungi are among the most widespread and enduring life forms on Earth.

Consider the desert, a landscape defined by its aridity and scorching temperatures. Here, fungal spores lie dormant, often for years, until conditions improve. Their ability to withstand desiccation is due to a combination of structural and biochemical adaptations. For instance, some spores reduce their metabolic activity to near-zero levels, conserving energy and resources. Others accumulate protective compounds like melanin, which shields them from UV radiation and oxidative stress. These strategies allow spores to remain viable, ready to germinate when moisture returns, ensuring the fungus’s survival across generations.

Chemical exposure poses another challenge, yet spores often emerge unscathed. Many fungi produce spores resistant to fungicides, herbicides, and even industrial pollutants. This resistance is partly due to their thick, chitinous cell walls, which act as a barrier against toxins. Additionally, some spores can repair DNA damage caused by chemicals, further enhancing their longevity. For example, *Aspergillus* spores have been found to survive in environments contaminated with heavy metals, showcasing their ability to thrive in hostile conditions. This resilience has practical implications, such as the need for higher doses of fungicides (e.g., 200–500 ppm of copper sulfate) to effectively control fungal growth in agricultural settings.

A comparative analysis highlights the superiority of spores over other reproductive units. Unlike seeds, which require specific conditions to remain viable, spores can persist in a dormant state for decades, even centuries. For instance, fungal spores trapped in Antarctic ice have been revived after 10,000 years, demonstrating their unparalleled durability. This longevity is a key factor in fungi’s ability to colonize new habitats, whether through wind dispersal or attachment to animals. By contrast, bacterial endospores, while similarly resilient, are less diverse in their dispersal mechanisms, limiting their ecological reach.

For those looking to harness or combat fungal resilience, practical tips can be derived from these survival strategies. Gardeners, for example, can improve soil health by incorporating organic matter, which encourages beneficial fungi while reducing the need for harsh chemicals. In industrial settings, understanding spore resistance can inform the development of more effective sterilization protocols, such as using heat treatments above 60°C for at least 30 minutes to ensure spore inactivation. Conversely, researchers studying extremophiles can model preservation techniques after spore adaptations, potentially advancing fields like food storage and space exploration. By studying these microscopic survivors, we gain insights into both preserving and overcoming life’s toughest challenges.

Effective Ways to Remove Mold Spores from Your Carpet

You may want to see also

Role in Life Cycle: Spores are key for fungal reproduction, germination, and genetic diversity in ecosystems

Fungi, unlike animals and plants, rely on spores as their primary means of reproduction. These microscopic, single-celled structures are akin to fungal "seeds," dispersed through air, water, or animals to colonize new environments. Spores are remarkably resilient, surviving harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and lack of nutrients. This adaptability ensures fungal survival across diverse ecosystems, from forest floors to human-made structures. Without spores, fungi would lack the mechanism to propagate and thrive in varied habitats, underscoring their critical role in the fungal life cycle.

Consider the process of spore germination, a pivotal phase in the fungal life cycle. When conditions are favorable—adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability—spores activate and develop into hyphae, the thread-like structures that form the fungal body. This transition from dormant spore to active fungus is essential for nutrient absorption and growth. For instance, in agricultural settings, understanding spore germination can help farmers manage fungal pathogens effectively. By controlling environmental factors like humidity and temperature, they can inhibit spore activation, reducing crop diseases. This practical application highlights the importance of spores in both natural and managed ecosystems.

Spores also drive genetic diversity, a cornerstone of ecosystem resilience. Fungi reproduce both asexually and sexually, with spores serving as vehicles for genetic exchange. Asexual spores, produced through mitosis, are clones of the parent fungus, ensuring rapid colonization. Sexual spores, formed through meiosis, combine genetic material from two parents, fostering diversity. This diversity is crucial for fungal adaptation to changing environments, such as resistance to antifungal agents. For example, in medical contexts, understanding spore-driven genetic variation helps researchers combat drug-resistant fungal infections, which affect millions globally, particularly immunocompromised individuals.

To harness the power of spores in ecosystems, consider these practical tips. In gardening, incorporate organic matter like compost to create a spore-friendly environment, promoting beneficial fungi that enhance soil health. In indoor spaces, monitor humidity levels (ideally below 60%) to discourage spore germination and prevent mold growth. For educational purposes, observe spore dispersal using a simple experiment: place a slice of bread in a sealed plastic bag, and within days, fungal spores will colonize it, demonstrating their ubiquitous presence. These actions illustrate how understanding spores can lead to tangible benefits in daily life and environmental management.

In conclusion, spores are not merely reproductive units but dynamic agents shaping fungal survival, growth, and evolution. Their role in germination ensures fungal proliferation, while their contribution to genetic diversity fosters ecosystem adaptability. By studying and applying this knowledge, we can manage fungi more effectively, whether in agriculture, medicine, or environmental conservation. Spores, though microscopic, wield macroscopic influence, embodying the intricate balance of life in ecosystems.

Unlocking Rogue and Epic Modes in Spore: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, most fungi reproduce by producing and dispersing spores, which are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures capable of developing into new fungal organisms.

Fungi produce various types of spores, including asexual spores (e.g., conidia) and sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, and basidiospores), depending on their life cycle and reproductive strategy.

Fungal spores disperse through air, water, animals, or other environmental factors. Some fungi actively eject spores, while others rely on wind, rain, or physical contact for dispersal.

While most fungi reproduce via spores, some species can also reproduce vegetatively through structures like hyphae fragmentation or budding, though spores remain the primary method.

Spores are crucial for fungal survival as they are highly resilient, allowing fungi to withstand harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, or lack of nutrients until favorable conditions return.