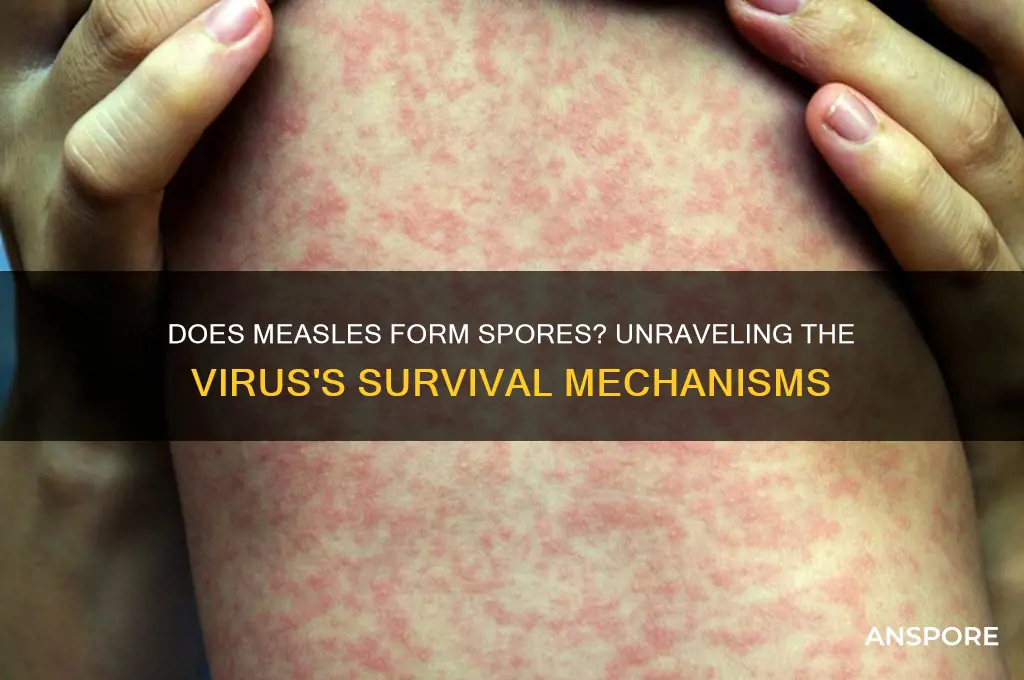

Measles, a highly contagious viral infection caused by the measles virus, is primarily known for its characteristic rash and respiratory symptoms. Unlike certain bacteria and fungi, the measles virus does not form spores as part of its life cycle. Spores are a dormant, resilient form of microorganisms that allow them to survive harsh environmental conditions, but viruses like measles rely on host cells to replicate and spread. Instead of forming spores, the measles virus is transmitted through respiratory droplets and remains viable in the air or on surfaces for a limited time. Understanding this distinction is crucial, as it highlights the virus's dependence on human hosts for survival and underscores the importance of vaccination and hygiene measures to prevent its spread.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Measles Form a Spore? | No |

| Type of Pathogen | Virus (Measles morbillivirus, a member of the Paramyxoviridae family) |

| Structure | Enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus; does not have a spore-like structure |

| Survival Outside Host | Short-lived in the environment (a few hours); does not form spores for long-term survival |

| Transmission | Airborne droplets or direct contact with nasal or throat secretions of infected individuals |

| Infectivity | Highly contagious but relies on active viral particles, not spores |

| Comparison to Spore-Forming Pathogens | Unlike bacteria such as Clostridium tetani (tetanus) or Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), measles virus does not produce spores |

| Environmental Resistance | Vulnerable to heat, sunlight, and disinfectants; does not form spores for resistance |

| Reactivation | No dormant spore stage; infection occurs only through active viral replication |

| Prevention | Vaccination (MMR vaccine) and isolation of infected individuals; no spore-specific measures required |

Explore related products

$19.99

What You'll Learn

- Measles Virus Structure: Measles is a single-stranded RNA virus, not a bacterium, so it cannot form spores

- Spore Formation Process: Spores are survival structures formed by certain bacteria and fungi, not viruses like measles

- Measles Transmission: Measles spreads via respiratory droplets, not through spore-like dormant forms

- Virus vs. Bacteria: Viruses lack cellular structure, preventing them from developing spore-like mechanisms

- Measles Survival Outside Host: Measles virus survives briefly outside the body but does not form spores

Measles Virus Structure: Measles is a single-stranded RNA virus, not a bacterium, so it cannot form spores

Measles, a highly contagious disease, is caused by a virus with a distinct structure that sets it apart from bacteria. At its core, the measles virus is a single-stranded RNA virus, belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family. This classification is crucial because it immediately rules out the possibility of spore formation, a process exclusively associated with certain bacteria and fungi. Unlike bacteria, which can transform into dormant spores to survive harsh conditions, viruses like measles lack the cellular machinery to undergo such transformations. Understanding this fundamental difference is essential for grasping why measles cannot form spores and how it behaves in the environment.

To appreciate why spore formation is irrelevant to measles, consider the virus’s replication cycle. The measles virus relies on host cells to replicate, as it cannot reproduce independently. Its structure consists of a helical nucleocapsid surrounded by a lipid envelope studded with glycoproteins, which facilitate entry into host cells. This envelope is fragile and susceptible to environmental factors like heat, sunlight, and disinfectants, rendering the virus inactive outside the host within hours. In contrast, bacterial spores are highly resilient, capable of surviving extreme conditions for years. This comparison highlights the measles virus’s vulnerability and its inability to form protective structures like spores.

From a practical standpoint, the measles virus’s inability to form spores has significant implications for infection control. Since the virus does not persist in the environment as spores do, standard disinfection practices are highly effective in eliminating it. Surfaces can be sanitized with common household disinfectants, and proper ventilation reduces viral particle concentration in the air. However, the virus’s primary mode of transmission remains respiratory droplets, emphasizing the importance of vaccination and isolation during outbreaks. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which require specialized decontamination methods, measles control relies on interrupting human-to-human transmission and strengthening immunity through vaccination.

Finally, the distinction between viruses and spore-forming organisms underscores the importance of accurate scientific understanding in public health. Misconceptions about measles forming spores could lead to ineffective control measures, such as overemphasizing environmental decontamination over vaccination. The measles virus’s single-stranded RNA structure and dependence on host cells for replication make it a prime target for vaccines, which have proven to be over 97% effective in preventing infection. By focusing on the virus’s unique biology, public health strategies can be tailored to combat measles effectively, ensuring that efforts are directed toward vaccination, early detection, and isolation rather than misguided attempts to address nonexistent spores.

Basidiomycete Pathogens Without Spores: Monocyclic or Not?

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Process: Spores are survival structures formed by certain bacteria and fungi, not viruses like measles

Spores are nature’s ultimate survival capsules, engineered by certain bacteria and fungi to endure extreme conditions. Unlike viruses like measles, which rely on living hosts to replicate and survive, spore-forming organisms create these dormant, highly resistant structures as a last resort. When nutrients are scarce or environments hostile—think scorching heat, freezing cold, or desiccating dryness—these microbes shut down their metabolic processes and form spores. This transformation is a biological marvel, allowing them to persist for years, even centuries, until conditions improve. Measles, being a virus, lacks this ability; it cannot form spores and is entirely dependent on human hosts for survival.

The spore formation process, or sporulation, is a complex, multi-step transformation. In bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* (the causative agent of anthrax), it begins with DNA replication and the formation of a protective layer around the genetic material. This layer, composed of proteins and peptidoglycan, is further encased in a tough outer coat that shields the spore from radiation, chemicals, and enzymes. Fungi, such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, follow a similar principle, though their spores (often called conidia) are typically lighter and more numerous, designed for wind dispersal. Both processes are energy-intensive and triggered only when survival is at stake, underscoring their role as a last-ditch survival mechanism.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore formation is critical in fields like medicine, food safety, and environmental science. Spores can contaminate surfaces, food, and even medical equipment, posing risks if not properly sterilized. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive boiling temperatures, requiring food to be heated to 121°C (250°F) for at least 3 minutes to ensure safety. In healthcare, autoclaves use steam under pressure to kill spores on surgical instruments. Unlike measles, which is inactivated by standard disinfectants like bleach, spores demand more aggressive measures, such as prolonged heat or specialized chemicals like hydrogen peroxide.

Comparatively, the inability of viruses like measles to form spores highlights their fragility outside a host. Measles virus particles degrade quickly in the environment, typically surviving only a few hours on surfaces. This is why measles transmission relies almost entirely on respiratory droplets from infected individuals. In contrast, bacterial and fungal spores can linger indefinitely, waiting for the right conditions to reactivate. This fundamental difference explains why measles outbreaks are controlled through vaccination and isolation, while spore-forming pathogens require rigorous sterilization protocols.

In conclusion, while measles and spore-forming organisms both pose health risks, their survival strategies are worlds apart. Spores are a testament to the resilience of certain microbes, offering them a second chance at life when all seems lost. Measles, however, is a transient threat, dependent on immediate transmission to thrive. Recognizing this distinction not only clarifies the biology of these pathogens but also informs how we combat them—whether through vaccines, disinfection, or sterilization.

Unveiling the Unique Appearance of Morel Spores: A Visual Guide

You may want to see also

Measles Transmission: Measles spreads via respiratory droplets, not through spore-like dormant forms

Measles, a highly contagious viral infection, relies on respiratory droplets for transmission, not spore-like dormant forms. Unlike bacteria such as *Clostridium tetani* (which forms spores to survive harsh conditions), the measles virus (MeV) is fragile outside the human body. It cannot persist in the environment for long periods and does not develop a protective spore structure. This biological limitation means measles spreads primarily through coughing, sneezing, or direct contact with infected nasal or throat secretions, not through environmental reservoirs. Understanding this distinction is crucial for implementing effective prevention strategies, such as vaccination and respiratory hygiene.

To prevent measles transmission, focus on interrupting the respiratory droplet pathway. The virus remains viable in the air or on surfaces for up to two hours after an infected person coughs or sneezes, but it degrades rapidly without a host. Practical measures include maintaining a distance of at least 3 feet from infected individuals, wearing masks in crowded settings, and frequently disinfecting high-touch surfaces. Vaccination remains the most effective method, with the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine providing 97% immunity after two doses. For infants under 12 months (who are too young for vaccination) and immunocompromised individuals, avoiding exposure to potentially infected individuals is critical.

Comparing measles transmission to spore-forming pathogens highlights the importance of tailored public health responses. While spores allow diseases like tetanus to persist in soil for decades, measles requires a continuous chain of human hosts to survive. This makes measles more susceptible to eradication through vaccination campaigns, as demonstrated by its elimination in many regions. However, its high transmissibility (R0 of 12–18) means even small gaps in immunity can lead to outbreaks. Unlike spore-based diseases, measles control relies on achieving herd immunity through vaccination rates of 93–95%, emphasizing the need for robust immunization programs.

A descriptive analysis of measles transmission reveals its dependence on human interaction and respiratory behaviors. The virus exits the body in microscopic droplets during coughing, sneezing, or even talking, traveling up to 6 feet before settling on surfaces or entering another person’s respiratory tract. In enclosed spaces like schools or healthcare facilities, the risk of transmission escalates due to prolonged exposure. Unlike spores, which can lie dormant indefinitely, measles virus particles require immediate transfer to a new host to survive. This transient nature underscores the effectiveness of time-sensitive interventions, such as isolating infected individuals within 4 days of rash onset to limit spread.

Persuasively, the absence of spore formation in measles should refocus public health efforts on human-centric interventions. While spore-based diseases demand environmental decontamination, measles control hinges on reducing person-to-person contact and bolstering immunity. Vaccination campaigns, particularly in underserved communities, are essential to disrupt transmission chains. Additionally, educating the public about respiratory etiquette—covering coughs, washing hands, and staying home when sick—can significantly curb outbreaks. By addressing measles’ unique transmission dynamics, societies can move closer to global eradication, a goal unattainable for spore-forming pathogens.

Can You See Truffle Spores? Unveiling the Mystery of Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Virus vs. Bacteria: Viruses lack cellular structure, preventing them from developing spore-like mechanisms

Measles, caused by the measles virus, is a highly contagious respiratory infection that spreads through airborne particles. Unlike bacteria, viruses lack cellular structure, which fundamentally limits their survival strategies. Bacteria, such as *Bacillus anthracis* (causative agent of anthrax), can form spores—dormant, highly resistant structures that enable long-term survival in harsh environments. Viruses, however, rely on host cells for replication and cannot produce spore-like mechanisms. This distinction is critical in understanding why measles cannot form spores and why its transmission depends on active infection rather than environmental persistence.

To illustrate, consider the lifecycle of the measles virus. It is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that infects respiratory cells and immune cells. Without a host, the virus degrades rapidly, typically within hours to days outside the body. In contrast, bacterial spores can survive for decades in soil, water, or on surfaces. For instance, *Clostridium tetani* spores, responsible for tetanus, can persist in soil for over 40 years. This disparity highlights the evolutionary trade-off: viruses prioritize rapid replication within hosts, while bacteria invest in long-term survival through sporulation.

From a practical standpoint, this difference informs prevention strategies. Measles control relies on vaccination and isolation of infected individuals, as the virus cannot survive independently for extended periods. The measles vaccine, administered in two doses (first at 12–15 months, second at 4–6 years), provides over 97% immunity. In contrast, bacterial infections like anthrax require decontamination of environments where spores may persist. For example, anthrax spores in soil are treated with formaldehyde or calcium hypochlorite to ensure eradication. Understanding these mechanisms helps tailor public health responses to the unique biology of pathogens.

Persuasively, the inability of viruses to form spores underscores the importance of vaccination. Measles outbreaks occur in unvaccinated populations, as the virus depends on susceptible hosts for transmission. In 2019, the WHO reported 869,770 measles cases globally, primarily in communities with low vaccination rates. Bacteria, however, pose risks even in vaccinated populations if spores contaminate environments. For instance, anthrax spores have been weaponized, requiring specialized containment protocols. This comparison emphasizes why viral diseases like measles are controllable through immunization, while bacterial threats often demand additional environmental interventions.

In conclusion, the absence of cellular structure in viruses precludes spore formation, shaping their ecology and control. Measles, as a viral disease, cannot persist outside hosts and is thus vulnerable to vaccination campaigns. Bacteria, with their sporulation ability, present distinct challenges requiring environmental management. Recognizing these differences equips healthcare professionals and policymakers to combat infections effectively, ensuring targeted strategies for each pathogen type.

Low Mold Spores: Hidden Dangers or Harmless Levels?

You may want to see also

Measles Survival Outside Host: Measles virus survives briefly outside the body but does not form spores

Measles virus, unlike some other pathogens, does not form spores. This distinction is crucial for understanding its survival and transmission dynamics. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow certain bacteria and fungi to endure harsh environmental conditions for extended periods. Measles, however, relies on its ability to remain viable in respiratory droplets and on surfaces for a short time, typically up to 2 hours, after which it rapidly loses infectivity. This brief survival window underscores the importance of immediate disinfection and isolation measures in outbreak settings.

Analyzing the implications of measles’ non-spore-forming nature reveals its vulnerability outside the host. Unlike spore-forming organisms, measles virus is susceptible to common disinfectants, ultraviolet light, and temperature extremes. For instance, a 10-minute exposure to sunlight or a 70% ethanol solution can effectively inactivate the virus. This sensitivity highlights the effectiveness of routine cleaning protocols in healthcare and public spaces. However, its airborne transmission via respiratory droplets remains a significant challenge, as these particles can travel and settle on surfaces, posing a risk until the virus degrades.

From a practical standpoint, preventing measles transmission hinges on leveraging its limited survival time outside the body. In healthcare settings, surfaces should be disinfected with EPA-approved products within 2 hours of potential exposure. For households, frequent cleaning of high-touch areas like doorknobs and countertops is essential, especially if an infected individual is present. Additionally, maintaining good ventilation reduces the concentration of airborne particles, further minimizing risk. These measures, combined with vaccination, form the cornerstone of measles control strategies.

Comparatively, the survival of measles outside the host contrasts sharply with spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* or anthrax, which can persist for years. This difference influences public health responses: while measles outbreaks require rapid, targeted interventions, spore-forming pathogens necessitate long-term environmental decontamination. Understanding this distinction helps allocate resources effectively, ensuring that measles control efforts focus on immediate disinfection and vaccination rather than prolonged environmental management.

In conclusion, the measles virus’ inability to form spores limits its environmental resilience but does not diminish its transmissibility. Its brief survival outside the host demands swift action to disrupt transmission chains. By focusing on timely disinfection, improving ventilation, and promoting vaccination, particularly among children aged 12–15 months and 4–6 years, communities can effectively curb measles outbreaks. This knowledge empowers individuals and healthcare providers to act decisively, turning the virus’ weakness into a strength for public health.

Glutaraldehyde's Effectiveness Against Spores: Can It Kill Them?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, measles does not form a spore. Measles is a viral infection caused by the measles virus, which is a single-stranded RNA virus. Spores are typically associated with bacteria and fungi, not viruses.

The measles virus can survive in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours, but it does not form spores. Its survival is limited compared to spore-forming bacteria, which can remain dormant for years.

No, no viruses, including measles, form spores. Spores are a survival mechanism unique to certain bacteria and fungi. Viruses rely on host cells to replicate and do not produce spores.