*Oenicillium*, a genus of fungi belonging to the family Trichocomaceae, is widely recognized for its diverse ecological roles, including as a biocontrol agent and a producer of bioactive compounds. One of the key characteristics of fungi is their reproductive structures, and in the case of *Oenicillium*, the presence of spores is a fundamental aspect of its life cycle. These spores, typically produced in specialized structures such as conidia, play a crucial role in the fungus's dispersal, survival, and colonization of new environments. Understanding whether *Oenicillium* has spores is essential for studying its biology, ecological impact, and potential applications in agriculture, medicine, and industry.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangia Formation: Oenicillium develops sporangia, structures that produce and contain spores for dispersal

- Asexual Spores: It primarily reproduces via asexual spores called conidia, formed on conidiophores

- Sexual Spores: Under certain conditions, Oenicillium can produce sexual spores (ascospores) in asci

- Spore Dispersal: Spores are dispersed through air, water, or insects, aiding in colonization and survival

- Spore Morphology: Spores are typically unicellular, dry, and vary in shape, aiding identification and classification

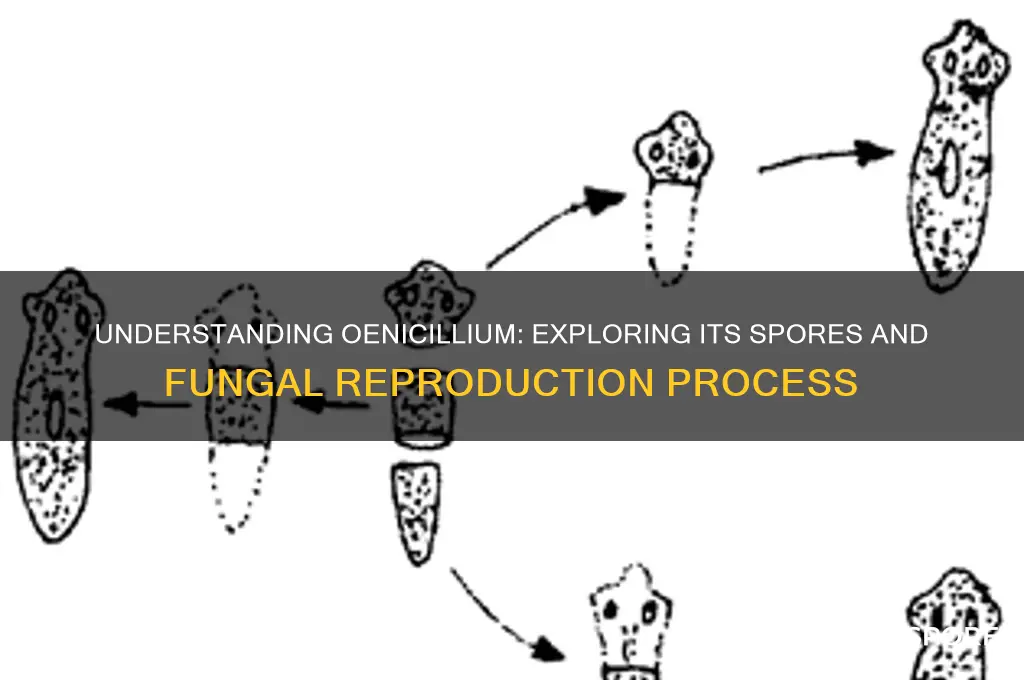

Sporangia Formation: Oenicillium develops sporangia, structures that produce and contain spores for dispersal

Oenicillium, a genus of fungi, employs a sophisticated reproductive strategy centered on sporangia formation. These structures, akin to microscopic factories, are the cornerstone of spore production and dispersal. Within each sporangium, spores develop in a protected environment, ensuring their viability until optimal conditions for release arise. This process is not merely a biological curiosity but a critical mechanism for the fungus’s survival and propagation in diverse ecosystems.

The formation of sporangia in Oenicillium is a multi-step process, beginning with the maturation of specialized cells called sporangiophores. These structures elongate and branch, providing a scaffold for sporangia to develop. As the sporangia mature, they become filled with spores, which are then encapsulated within a protective wall. This encapsulation is crucial, as it shields the spores from environmental stressors such as desiccation, predation, and UV radiation. The timing and efficiency of sporangia formation are influenced by environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and nutrient availability, highlighting the fungus’s adaptability.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporangia formation in Oenicillium has implications for both agriculture and biotechnology. For instance, in biocontrol applications, the fungus is used to combat plant pathogens. Maximizing sporangia production can enhance its efficacy, as more spores mean greater coverage and colonization potential. To achieve this, growers can manipulate environmental conditions: maintaining relative humidity above 80% and temperatures between 20–25°C fosters optimal sporangia development. Additionally, providing a substrate rich in organic matter, such as compost or plant debris, can accelerate the process.

Comparatively, Oenicillium’s sporangia formation differs from that of other fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, which produce conidia directly on phialides. Oenicillium’s sporangia are more robust and better suited for long-distance dispersal, making it particularly effective in colonizing new habitats. This distinction underscores its ecological role as a pioneer species in nutrient cycling and soil health. For researchers and practitioners, this knowledge can inform strategies for harnessing Oenicillium’s potential in bioremediation or sustainable agriculture.

In conclusion, sporangia formation in Oenicillium is a finely tuned process that ensures the fungus’s reproductive success and ecological impact. By producing and encapsulating spores within sporangia, Oenicillium not only safeguards its genetic material but also enhances its dispersal capabilities. Whether in the lab or the field, optimizing this process can amplify the fungus’s benefits, from pest control to environmental restoration. Understanding the intricacies of sporangia formation is thus key to leveraging Oenicillium’s full potential.

Exploring the Connection: Are Darkspore and Spore Related Games?

You may want to see also

Asexual Spores: It primarily reproduces via asexual spores called conidia, formed on conidiophores

Oenicillium, a genus of fungi, relies heavily on asexual reproduction to propagate and survive in diverse environments. At the heart of this process are conidia, specialized asexual spores that serve as the primary means of dispersal. These spores are not merely passive agents; they are the lifeblood of the fungus, enabling it to colonize new habitats, evade predators, and endure harsh conditions. Understanding how conidia form and function is key to appreciating the resilience and adaptability of Oenicillium.

The formation of conidia begins on structures called conidiophores, which act as spore-producing factories. These elongated, filamentous cells are strategically positioned to maximize spore dispersal. As conidiophores mature, they develop clusters of conidia at their tips, often arranged in a chain-like or branched pattern. This arrangement is not arbitrary; it optimizes the release of spores into the air or surrounding medium, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization. For instance, in laboratory settings, conidia production can be enhanced by maintaining optimal humidity levels (around 80-90%) and temperatures (22-28°C), conditions that mimic the fungus’s natural habitat.

From a practical standpoint, the asexual spores of Oenicillium are invaluable in biotechnology and agriculture. Conidia are used as bioagents in pest control, particularly against insect larvae that damage crops. A single gram of conidia can contain millions of spores, making it an efficient and cost-effective solution. To apply, mix the conidia with a carrier like talcum powder or water, ensuring even distribution. Spraying should be done early in the morning or late in the evening when humidity is high, as this prolongs spore viability and enhances adhesion to target surfaces.

Comparatively, the asexual reproduction of Oenicillium contrasts with that of other fungi that rely on sexual spores or vegetative propagation. While sexual spores offer genetic diversity, conidia provide rapid multiplication and immediate adaptation to stable environments. This makes Oenicillium particularly effective in controlled settings, such as bioreactors or greenhouses, where consistency is crucial. For example, in mycoinsecticide production, conidia are harvested after 7-10 days of growth, a significantly shorter cycle than sexual spore development, which can take weeks.

In conclusion, the asexual spores of Oenicillium, known as conidia, are a testament to the fungus’s evolutionary ingenuity. Formed on conidiophores, these spores are not just a means of reproduction but a tool for survival and expansion. Whether in nature or applied science, their role is undeniable, offering both ecological balance and practical solutions. By harnessing their potential, we unlock new possibilities in agriculture, biotechnology, and beyond.

Casting Spores on Molt: Techniques, Timing, and Effective Strategies Explained

You may want to see also

Sexual Spores: Under certain conditions, Oenicillium can produce sexual spores (ascospores) in asci

Oenicillium, a genus of fungi, is known for its asexual spore production, but under specific conditions, it can also engage in sexual reproduction, forming ascospores within asci. This process is not only fascinating from a biological standpoint but also has implications for its ecological role and biotechnological applications. Understanding the conditions that trigger sexual spore formation is crucial for researchers and practitioners in fields ranging from agriculture to biotechnology.

To induce sexual spore production in Oenicillium, certain environmental factors must align. These include specific temperature ranges, typically between 20°C and 25°C, and a controlled humidity level, often around 80-90%. Additionally, the presence of compatible mating types is essential, as Oenicillium is heterothallic, requiring two different strains to initiate sexual reproduction. Nutrient availability also plays a critical role; a medium rich in carbon and nitrogen sources, such as potato dextrose agar supplemented with vitamins, can enhance the likelihood of ascospore formation.

The process of ascospore development in Oenicillium is a complex, multi-step sequence. It begins with the fusion of hyphae from compatible strains, forming a dikaryotic mycelium. This is followed by the development of asci, sac-like structures that house the ascospores. Each ascus typically contains eight ascospores, which are haploid and genetically diverse, a key advantage of sexual reproduction. These spores are then released into the environment, where they can germinate under favorable conditions, ensuring the survival and propagation of the species.

From a practical perspective, the ability to produce sexual spores in Oenicillium opens up new avenues for genetic studies and biotechnological applications. For instance, the genetic diversity generated through sexual reproduction can be harnessed to develop strains with enhanced biocontrol capabilities against plant pathogens. Researchers can manipulate the conditions described above to cultivate and study these sexual spores, potentially leading to breakthroughs in sustainable agriculture and fungal biotechnology.

In conclusion, while Oenicillium is primarily recognized for its asexual spore production, its capacity for sexual reproduction under specific conditions is a significant yet underutilized aspect of its biology. By understanding and controlling the factors that promote ascospore formation, scientists can unlock new possibilities for research and application, highlighting the importance of exploring the full reproductive potential of this versatile fungus.

Farming Spore Blossoms: Feasibility, Techniques, and Potential Benefits Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Dispersal: Spores are dispersed through air, water, or insects, aiding in colonization and survival

Spores, the microscopic survival units of fungi like *Oenicillium*, are not just passive entities waiting to germinate. Their dispersal mechanisms—air, water, and insects—are finely tuned strategies for colonization and persistence. Air dispersal, for instance, leverages wind currents to carry lightweight spores over vast distances, a process akin to nature’s own aerial seeding. This method ensures that *Oenicillium* can reach new habitats, from soil to decaying matter, where it thrives. Water, too, plays a dual role: it transports spores through rain splash or runoff and provides a medium for germination once they land in suitable environments. Insects, often unwitting carriers, pick up spores on their bodies as they forage, dispersing them to new locations as they move. Together, these mechanisms form a robust network that maximizes the fungus’s chances of survival and proliferation.

Consider the practical implications of spore dispersal in agricultural or laboratory settings. For farmers, understanding these mechanisms can inform strategies to control or harness *Oenicillium*. For example, reducing standing water or managing airflow in greenhouses can limit unwanted spore spread. Conversely, in biotechnological applications, such as using *Oenicillium* for biocontrol of pests, optimizing spore dispersal through targeted water sprays or insect vectors could enhance its efficacy. Dosage matters here: a controlled release of spores (e.g., 10^6 spores per liter of water) can ensure effective colonization without waste. Age categories of crops or substrates also play a role—younger plants may be more susceptible to colonization, making early intervention critical.

From a comparative perspective, *Oenicillium*’s spore dispersal strategies share similarities with other fungi but also exhibit unique adaptations. Unlike heavier spores of some basidiomycetes, *Oenicillium*’s asexual spores (conidia) are smaller and more numerous, ideal for wind dispersal. This contrasts with fungi like truffles, which rely heavily on animals for dispersal. Such differences highlight the evolutionary fine-tuning of spore traits to specific ecological niches. For instance, *Oenicillium*’s ability to produce spores rapidly in response to environmental cues (e.g., nutrient availability) gives it an edge in competitive ecosystems.

Descriptively, imagine a forest floor after a rainstorm: water droplets splash against decaying wood, dislodging *Oenicillium* spores that float upward, catching the breeze. Nearby, a beetle scurries across the damp surface, its exoskeleton now carrying spores to its next destination. This vivid scene underscores the interconnectedness of dispersal methods and their synergy in ensuring the fungus’s success. Each mechanism complements the others, creating a resilient system that adapts to environmental challenges.

Finally, a persuasive argument for appreciating spore dispersal lies in its ecological and applied significance. By studying how *Oenicillium* spreads, we gain insights into fungal ecology and potential biotechnological uses. For instance, its ability to colonize diverse substrates through efficient dispersal makes it a candidate for bioremediation of polluted soils. Practical tips for researchers include mimicking natural dispersal in lab settings—using air pumps or water sprays to simulate wind and rain—to study colonization dynamics. In essence, spore dispersal is not just a biological process but a key to unlocking *Oenicillium*’s potential in science and industry.

Do Horsetails Have Spores? Unveiling Their Ancient Reproductive Secrets

You may want to see also

Spore Morphology: Spores are typically unicellular, dry, and vary in shape, aiding identification and classification

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi, exhibit a morphology that is both fascinating and functionally critical. Typically unicellular and dry, these structures are designed for survival and dispersal. Their shapes vary widely—from spherical to elongated, smooth to ornamented—each adaptation serving a purpose in the fungus’s lifecycle. For *Oenicillium*, a genus of fungi known for its role in biodegradation and biocontrol, spore morphology is a key diagnostic feature. The asexual spores, or conidia, are often cylindrical or oval, with distinct septation patterns that distinguish species within the genus. This variability in shape is not arbitrary; it reflects evolutionary pressures such as environmental conditions and dispersal mechanisms.

Analyzing spore morphology requires precision tools like light microscopy or scanning electron microscopy to capture details such as size, color, and surface texture. For instance, *Oenicillium* spores typically measure 5–10 μm in length, with a smooth or slightly roughened surface. These characteristics are crucial for taxonomists, who rely on such features to classify species accurately. In practical terms, understanding spore morphology can aid in identifying beneficial strains of *Oenicillium* for applications like mycoinsecticides or enzyme production. For researchers, documenting spore dimensions and shapes in standardized units (e.g., micrometers) ensures consistency across studies.

From a comparative perspective, *Oenicillium* spores differ from those of closely related genera like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*. While *Aspergillus* produces chain-like conidial heads, *Oenicillium* often forms clusters or short chains with distinct separation between spores. This distinction is vital for avoiding misidentification, which could lead to incorrect applications in biotechnology or agriculture. For example, mistaking *Oenicillium* for *Penicillium* might result in using the wrong fungus for antibiotic production, as *Penicillium* is renowned for penicillin synthesis, while *Oenicillium* excels in degrading plastics.

Persuasively, the study of spore morphology is not merely academic—it has tangible applications. In biocontrol, knowing the spore shape and size of *Oenicillium* can optimize its use against pests like mites or nematodes. For instance, smaller spores may disperse more easily in soil, while larger ones might adhere better to insect cuticles. Practical tips include using spore suspensions at concentrations of 10^6–10^8 spores/mL for field applications, ensuring adequate coverage without waste. Additionally, storing spores in desiccated conditions at 4°C preserves their viability for months, a critical consideration for commercial formulations.

Descriptively, the beauty of *Oenicillium* spores lies in their simplicity and efficiency. Under a microscope, they appear as tiny, streamlined structures, each a potential new organism. Their dry nature ensures longevity, allowing them to withstand harsh conditions until they encounter a suitable substrate for germination. This adaptability is a testament to the ingenuity of fungal evolution. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, observing these spores firsthand can deepen appreciation for the microbial world, bridging the gap between abstract science and tangible biology. Whether in a lab or a field, spore morphology remains a cornerstone of fungal study, offering insights into both fundamental biology and applied solutions.

Does Milky Spore Really Work? Uncovering the Truth for Your Lawn

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Oenicillium, like other fungi in the genus, produces spores as part of its reproductive cycle.

Oenicillium produces asexual spores called conidia, which are typically borne on specialized structures called conidiophores.

Yes, Oenicillium spores are lightweight and can become airborne, allowing them to disperse and colonize new environments.

Oenicillium spores are formed through asexual reproduction, where conidia develop on the conidiophores and are released into the environment.

Yes, Oenicillium spores are known for their resilience and can survive in a variety of environments, including harsh conditions, until they find suitable conditions to germinate.