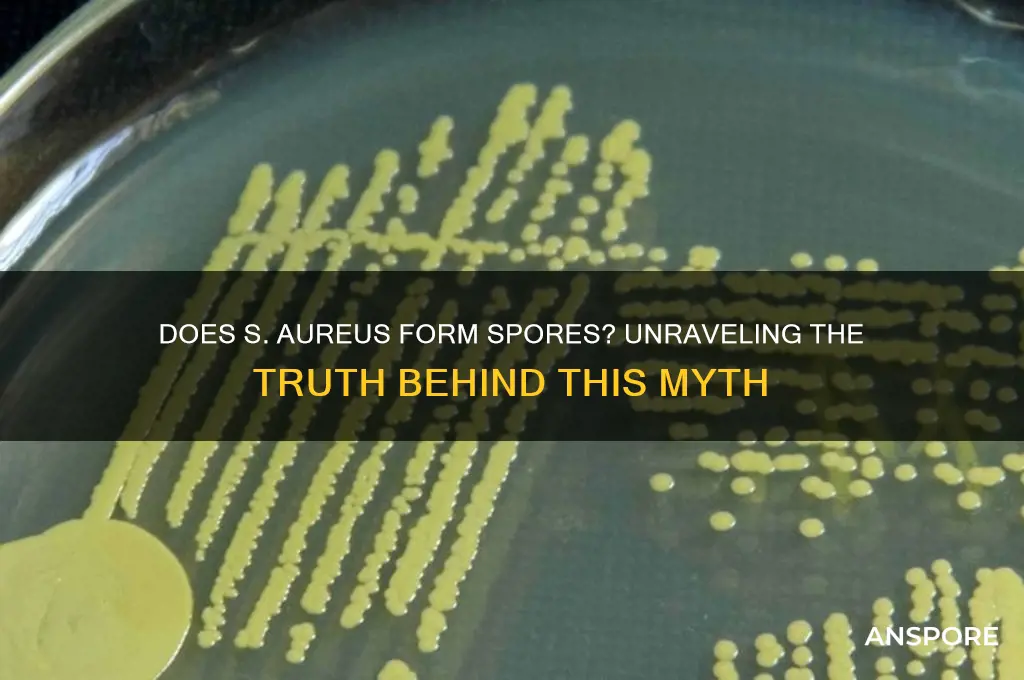

*Staphylococcus aureus*, a gram-positive bacterium commonly found on the skin and in the nasal passages of humans, is known for its ability to cause a wide range of infections, from minor skin conditions to severe systemic diseases. Despite its adaptability and resilience, *S. aureus* does not form spores, a characteristic that distinguishes it from other bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions, but *S. aureus* relies instead on its ability to produce biofilms and persist in diverse environments through other mechanisms, such as antibiotic resistance and rapid mutation. Understanding its lack of spore formation is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat *S. aureus* infections and prevent its spread.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

S. aureus spore formation mechanism

Staphylococcus aureus, a notorious pathogen responsible for a range of infections from minor skin abscesses to life-threatening conditions like sepsis, has long been studied for its survival strategies. One question that often arises is whether S. aureus forms spores, a highly resistant dormant structure seen in other bacteria like Clostridium difficile. The short answer is no—S. aureus does not form spores. However, understanding why this is the case and exploring its alternative survival mechanisms sheds light on its remarkable adaptability in diverse environments.

To comprehend why S. aureus lacks spore formation, consider the genetic and metabolic basis of sporulation. Spore-forming bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis, rely on a complex regulatory network involving genes like *spo0A* and *sigE*. S. aureus lacks these critical genes, rendering it incapable of initiating the sporulation process. Instead, it employs other strategies to endure harsh conditions, such as biofilm formation and the production of persistent cells. These mechanisms, while not as robust as spores, allow S. aureus to survive in nutrient-poor environments, on medical devices, and even within host tissues during infection.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in S. aureus has significant implications for infection control and treatment. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which require extreme measures like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes, S. aureus can be effectively eliminated with standard disinfection protocols. For instance, ethanol-based hand sanitizers (at least 60% ethanol) and quaternary ammonium compounds are sufficient to inactivate S. aureus on surfaces. However, its ability to form biofilms on medical devices, such as catheters, necessitates more rigorous cleaning methods, including mechanical scrubbing and enzymatic cleaners, to disrupt the protective matrix.

Comparatively, the survival strategies of S. aureus highlight its evolutionary trade-offs. While spore-forming bacteria invest energy in producing highly resistant spores, S. aureus allocates resources to rapid replication and toxin production, enabling it to exploit host vulnerabilities swiftly. This distinction is crucial in clinical settings, where S. aureus infections often require prompt antibiotic intervention. For example, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections are typically treated with vancomycin (15–20 mg/kg every 8–12 hours) or linezolid (600 mg every 12 hours), emphasizing the need to target actively growing cells rather than dormant spores.

In conclusion, while S. aureus does not form spores, its alternative survival mechanisms—biofilm formation, persistent cells, and rapid adaptation—make it a formidable pathogen. Understanding these strategies not only clarifies its inability to sporulate but also informs effective prevention and treatment approaches. By focusing on disrupting biofilms and targeting active bacterial cells, healthcare providers can mitigate the risks posed by this resilient organism.

How Long Can Mold Spores Survive Without Moisture?

You may want to see also

Environmental conditions for sporulation

Staphylococcus aureus does not form spores under any environmental conditions, a fact that distinguishes it from spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium or Bacillus. However, understanding the environmental conditions that trigger sporulation in other bacteria can provide insight into why S. aureus lacks this survival mechanism. Sporulation is a complex, energy-intensive process typically induced by nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources. For spore-forming bacteria, this stress response ensures long-term survival in harsh environments. In contrast, S. aureus relies on other strategies, such as biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance, to endure adverse conditions.

Analyzing the sporulation process in bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis* reveals key environmental triggers: starvation, high salinity, and extreme temperatures. For instance, a carbon source concentration below 0.05% (w/v) in the growth medium can initiate sporulation in *B. subtilis*. Similarly, a nitrogen-to-carbon ratio of less than 0.1 signals nutrient depletion, prompting the cell to enter the sporulation pathway. These conditions are tightly regulated by sigma factors and signaling molecules, ensuring the process is only activated when necessary. *S. aureus*, lacking the genetic machinery for sporulation, instead responds to stress by altering gene expression to enhance survival without forming spores.

From a practical standpoint, preventing sporulation in spore-forming pathogens is critical in healthcare and food safety settings. For example, maintaining temperatures above 121°C for at least 15 minutes during sterilization effectively destroys spores. In contrast, *S. aureus* is more susceptible to heat, with most strains inactivated at 70°C within 30 minutes. This difference highlights the importance of tailoring disinfection protocols to the specific survival mechanisms of the target organism. While *S. aureus* does not form spores, understanding sporulation conditions in other bacteria underscores the need for rigorous environmental control to prevent contamination.

Comparatively, the absence of sporulation in *S. aureus* shifts the focus to its other survival strategies, such as persister cell formation and antibiotic resistance. Persister cells, a small subpopulation of dormant cells, tolerate antibiotic treatment without genetic mutation. These cells can revive once conditions improve, contributing to recurrent infections. Unlike spores, persister cells are not as resilient to extreme conditions but pose a significant challenge in clinical settings. This distinction emphasizes the need for targeted interventions that address *S. aureus*’s unique survival mechanisms rather than those of spore-forming bacteria.

In conclusion, while *S. aureus* does not form spores, exploring the environmental conditions for sporulation in other bacteria provides valuable context for understanding microbial survival strategies. Nutrient deprivation, particularly of carbon and nitrogen, is a universal trigger for stress responses, but *S. aureus* adapts through alternative mechanisms. This knowledge informs effective disinfection practices and highlights the importance of addressing organism-specific survival tactics in infection control. By focusing on *S. aureus*’s unique biology, healthcare and research professionals can develop more targeted strategies to combat this persistent pathogen.

Can Dettol Effectively Eliminate Ringworm Spores? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Comparison with spore-forming bacteria

Staphylococcus aureus, a common human pathogen, does not form spores, a stark contrast to bacteria like Clostridium botulinum and Bacillus anthracis. These spore-forming bacteria can survive extreme conditions—heat, radiation, and desiccation—by entering a dormant, highly resistant state. S. aureus, however, relies on its ability to rapidly adapt to environments through genetic flexibility and biofilm formation, rather than spore production. This fundamental difference in survival strategies influences their clinical management and environmental persistence.

Analyzing the implications, spore-forming bacteria pose unique challenges in healthcare and food safety due to their resilience. For instance, *C. difficile* spores can persist on surfaces for months, requiring specialized disinfectants like chlorine-based cleaners (1,000 ppm) for effective decontamination. In contrast, S. aureus is more susceptible to standard disinfectants (e.g., 70% ethanol) but thrives in warm, nutrient-rich environments like nasal passages or wounds. Understanding these differences is critical for infection control: while spore-formers demand aggressive decontamination protocols, S. aureus control focuses on hygiene and rapid treatment with antibiotics like cefazolin (1-2 g IV every 8 hours for adults).

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in S. aureus simplifies its eradication in clinical settings but complicates its long-term survival outside hosts. Spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus cereus*, can contaminate food even after cooking, as spores survive temperatures up to 100°C. S. aureus, however, is primarily transmitted via direct contact or fomites, making hand hygiene and wound care paramount. For example, in a hospital setting, isolating patients with MRSA (methicillin-resistant S. aureus) and using contact precautions reduces transmission, whereas spore-formers require additional environmental decontamination measures.

Persuasively, the non-spore-forming nature of S. aureus highlights its vulnerability to environmental stressors, making it a target for prevention rather than eradication. Unlike spores, which necessitate high-intensity interventions (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes), S. aureus can be controlled through routine practices like surface cleaning and antibiotic stewardship. However, its ability to develop resistance (e.g., to methicillin or vancomycin) underscores the need for judicious antibiotic use. In contrast, spore-formers’ intrinsic resistance mechanisms demand alternative strategies, such as toxin neutralization in *C. botulinum* infections with antitoxins.

In conclusion, comparing S. aureus to spore-forming bacteria reveals distinct survival and management strategies. While spore-formers excel in long-term persistence and resistance, S. aureus leverages adaptability and rapid proliferation. Clinicians and infection control specialists must tailor their approaches: for S. aureus, focus on prevention and early treatment; for spore-formers, prioritize environmental decontamination and specialized interventions. This nuanced understanding ensures effective control of both bacterial types in diverse settings.

Daylight's Role in Eliminating Mold Spores: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Clinical implications of spore absence

Staphylococcus aureus, a common pathogen responsible for a range of infections from skin abscesses to life-threatening sepsis, does not form spores. This absence of spore formation has significant clinical implications, particularly in the context of infection control, treatment strategies, and patient outcomes. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Clostridium difficile, S. aureus relies on vegetative cells for survival and transmission, which are more susceptible to environmental stressors and disinfectants. This biological characteristic influences how healthcare settings approach disinfection protocols and infection prevention measures.

From an infection control perspective, the non-spore-forming nature of S. aureus simplifies decontamination efforts in clinical environments. Standard disinfection methods, such as alcohol-based hand sanitizers (at least 60% ethanol or 70% isopropanol) and quaternary ammonium compounds, are highly effective against vegetative cells. However, this also means that transient colonization on skin and surfaces is more common, necessitating rigorous hand hygiene and environmental cleaning. For example, in intensive care units, daily disinfection of high-touch surfaces with sodium hypochlorite (0.5% solution) can significantly reduce S. aureus transmission, especially in outbreaks of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

The absence of spores also impacts treatment strategies. Since S. aureus does not form a dormant, resistant spore state, antibiotics can effectively target actively dividing cells. However, the emergence of antibiotic resistance, particularly in MRSA, complicates therapy. Clinicians must rely on culture and sensitivity testing to guide treatment, often using agents like vancomycin (15–20 mg/kg every 8–12 hours for adults) or daptomycin (4–6 mg/kg daily). The inability of S. aureus to form spores means that treatment focuses on eradicating vegetative cells, but recurrent infections remain a challenge due to persistent colonization in the nasal cavity or skin.

Comparatively, the clinical management of spore-forming bacteria like C. difficile requires additional strategies, such as spore-targeted disinfectants (e.g., bleach) and fecal microbiota transplantation. In contrast, S. aureus control relies on interrupting transmission chains through hygiene measures and prompt treatment. For instance, in surgical settings, preoperative nasal decolonization with mupirocin (2% ointment applied twice daily for 5 days) reduces the risk of postoperative infections, particularly in high-risk procedures like cardiothoracic surgery.

In summary, the absence of spore formation in S. aureus simplifies disinfection but demands vigilant infection control practices to prevent transmission. Clinicians must focus on early detection, appropriate antibiotic use, and decolonization strategies to manage infections effectively. Understanding this biological trait underscores the importance of tailored approaches in combating S. aureus, distinct from those required for spore-forming pathogens.

Bamboo Charcoal's Effectiveness Against Black Mold Spores: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Research on S. aureus sporulation potential

Staphylococcus aureus, a notorious pathogen responsible for a range of infections from mild skin conditions to life-threatening sepsis, has long been classified as a non-spore-forming bacterium. However, recent research has begun to challenge this assumption, exploring the potential for S. aureus to form spore-like structures under specific environmental conditions. This emerging area of study has significant implications for understanding the bacterium's survival mechanisms and its ability to persist in hostile environments.

One of the key findings in this research is the identification of subpopulations of S. aureus that exhibit spore-like characteristics under stress conditions, such as nutrient deprivation or exposure to antibiotics. These structures, often referred to as "persister cells," share some morphological and functional similarities with spores, including increased resistance to heat, desiccation, and antimicrobial agents. For instance, studies have shown that certain strains of S. aureus can enter a dormant state, reducing their metabolic activity and forming a protective outer layer that enhances survival in adverse conditions. This phenomenon has been observed in both laboratory settings and clinical isolates, suggesting that it may play a role in the bacterium's ability to cause recurrent infections.

To investigate the sporulation potential of S. aureus, researchers have employed a variety of techniques, including electron microscopy, molecular biology, and bioinformatics. For example, transcriptomic analyses have revealed that S. aureus can upregulate genes associated with stress response and cell wall modification under conditions that mimic environmental stress. These genetic changes are thought to contribute to the formation of spore-like structures. Additionally, experiments involving exposure to sub-lethal doses of antibiotics (e.g., 0.5x minimum inhibitory concentration) have demonstrated that such conditions can induce the development of persister cells, which may serve as a precursor to spore-like formations.

Despite these advancements, the research on S. aureus sporulation potential is still in its infancy, and many questions remain unanswered. For instance, the exact mechanisms by which S. aureus forms spore-like structures are not fully understood, nor is it clear whether these structures are true spores or simply highly resistant cells. Furthermore, the clinical relevance of this phenomenon is yet to be fully established. Are these spore-like structures responsible for the persistence of S. aureus in healthcare settings, or do they primarily play a role in environmental survival? Answering these questions will require further interdisciplinary research, combining microbiology, genetics, and clinical studies.

Practical implications of this research extend to infection control and treatment strategies. If S. aureus can indeed form spore-like structures, current disinfection protocols and antibiotic regimens may need to be reevaluated. For example, healthcare facilities might need to adopt more stringent cleaning procedures, such as the use of sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide vapor or chlorine dioxide, to effectively eliminate these resistant forms. Similarly, in clinical practice, understanding the sporulation potential of S. aureus could lead to the development of novel therapeutic approaches, such as combination therapies that target both actively growing cells and dormant, spore-like forms.

In conclusion, while S. aureus is traditionally considered a non-spore-forming bacterium, emerging research suggests that it may possess the ability to form spore-like structures under certain conditions. This discovery opens new avenues for understanding the bacterium's survival strategies and has significant implications for infection control and treatment. As research in this area continues to evolve, it will be crucial to translate these findings into practical applications that improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden of S. aureus infections.

Exploring Interworld Interactions: Can You Connect with Other Worlds in Spore?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) does not form spores. It is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

S. aureus lacks the genetic machinery required for sporulation, which is a process typically seen in other bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium.

Yes, S. aureus can survive in harsh conditions through other mechanisms, such as forming biofilms or entering a dormant state, but it does not form spores.

No, none of the staphylococcal species, including S. aureus, are known to form spores.

The lack of spore formation means S. aureus relies on other methods for transmission, such as direct contact, contaminated surfaces, or respiratory droplets, rather than spore-mediated survival and dispersal.