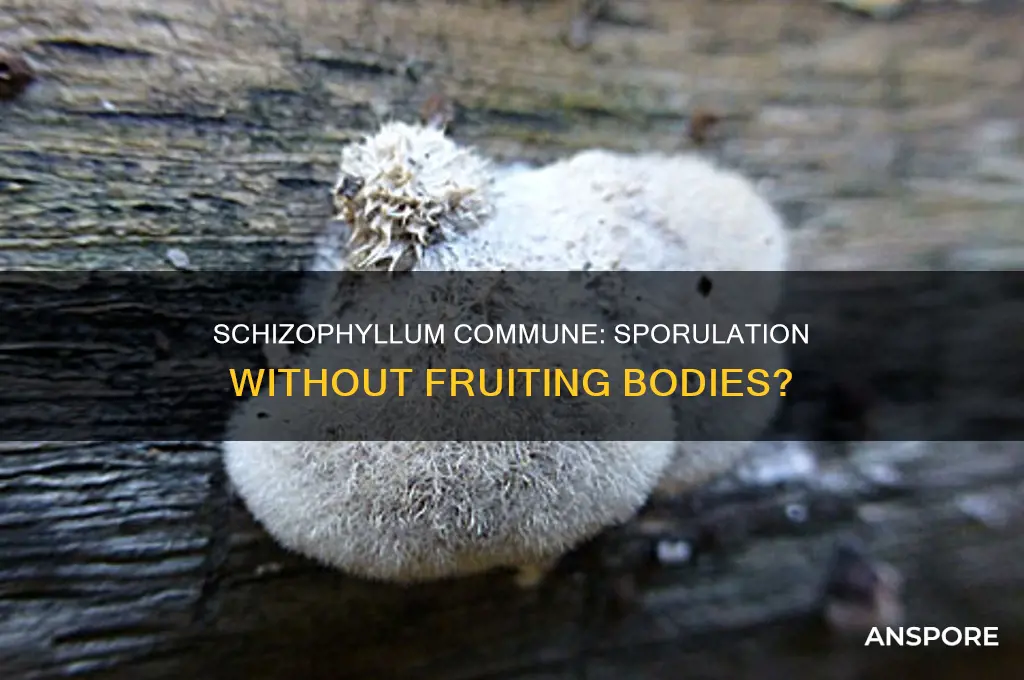

Schizophyllum commune, a common wood-rotting fungus, is known for its unique ability to form bracket-like fruiting bodies on decaying wood. However, the question arises whether this fungus can emit spores even in the absence of visible fruiting structures. This inquiry is significant because it challenges the traditional understanding that spore production is exclusively linked to the development of fruiting bodies. Investigating the potential for spore emission outside of fruiting could provide insights into the fungus's dispersal mechanisms, ecological impact, and survival strategies, particularly in environments where fruiting may be inhibited or less frequent. Understanding this aspect of Schizophyllum commune's biology could also have implications for its role in wood decay processes and its interactions with other organisms in its habitat.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporulation without Fruiting Bodies | Schizophyllum commune can emit spores even in the absence of visible fruiting bodies. |

| Mechanism | Spores are produced directly from mycelium or substrate, bypassing the typical fruiting body stage. |

| Environmental Conditions | Sporulation without fruiting is more likely under stress conditions (e.g., nutrient limitation, dryness) or in specific growth media. |

| Spores Produced | The spores emitted are typically asexual spores (conidia) rather than basidiospores, which are associated with fruiting bodies. |

| Ecological Significance | This ability allows S. commune to persist and disperse in environments where fruiting body formation is unfavorable. |

| Research Evidence | Studies have demonstrated spore production in pure culture and under controlled conditions without fruiting body development. |

| Practical Implications | Highlights the fungus's adaptability and potential for airborne dispersal even in non-optimal conditions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporulation without fruiting bodies

Schizophyllum commune, a ubiquitous fungus known for its resilience and adaptability, challenges our understanding of fungal reproduction. While typically associated with the formation of distinctive fruiting bodies, recent studies suggest that this species may possess the ability to sporulate without the visible presence of these structures. This phenomenon raises intriguing questions about the mechanisms and conditions under which S. commune can disperse its spores, potentially expanding its ecological reach and impact.

The Mechanism of Sporulation

In traditional fungal reproduction, sporulation is intimately linked to the development of fruiting bodies, which provide structure and protection for spore formation. However, S. commune appears to defy this convention. Research indicates that under specific environmental conditions, such as nutrient limitation or physical confinement, the fungus can initiate sporulation without the need for a mature fruiting body. This process likely involves the direct conversion of vegetative hyphae into spore-producing structures, bypassing the typical developmental stages.

Environmental Triggers and Conditions

To induce sporulation without fruiting bodies, certain environmental factors must be carefully manipulated. For instance, maintaining a temperature range of 20-25°C and a relative humidity above 80% can create favorable conditions for this alternative sporulation pathway. Additionally, providing a substrate with limited nitrogen sources, such as 0.1% ammonium sulfate, has been shown to stimulate spore production in the absence of fruiting bodies. These specific requirements highlight the fungus's ability to adapt its reproductive strategy in response to environmental cues.

Implications and Applications

The discovery of sporulation without fruiting bodies in S. commune has significant implications for various fields. In biotechnology, this phenomenon could be harnessed for the large-scale production of spores, which are valuable in enzyme production and biocontrol applications. For example, spores of S. commune are known to produce lignin-degrading enzymes, making them useful in biofuel production and paper pulp processing. By optimizing conditions for sporulation without fruiting bodies, researchers can potentially increase spore yields and reduce production costs.

Practical Considerations and Cautions

When attempting to induce sporulation without fruiting bodies in S. commune, it is essential to monitor the process closely. Regular microscopic examination of the culture can help identify the early stages of spore formation, ensuring that the desired outcome is achieved. Moreover, maintaining sterile conditions is crucial to prevent contamination, which can interfere with spore production and compromise the experiment's results. For those working with this fungus, it is advisable to start with a pure culture and use aseptic techniques throughout the process. By understanding and controlling the factors that influence this unique form of sporulation, researchers and practitioners can unlock new possibilities for studying and utilizing S. commune in various applications.

Are Cubensis Spores Harmful to Dogs? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for spore release

Schizophyllum commune, a common wood-rotting fungus, is known for its unique ability to release spores even in the absence of visible fruiting bodies. This phenomenon raises questions about the environmental triggers that prompt spore release. While the fungus is often associated with its distinctive fan-shaped fruiting bodies, it can disperse spores through alternative mechanisms, such as the ejection of ballistospores from microscopic structures called sterigmata. Understanding these triggers is crucial for managing fungal growth and spore dispersal in various environments, from forests to indoor spaces.

Analyzing the role of humidity reveals its significance as a primary environmental trigger for spore release in Schizophyllum commune. Research indicates that spore discharge increases under conditions of high relative humidity, typically above 90%. This is because water vapor facilitates the swelling of sterigmata, generating the surface tension required to propel spores into the air. For instance, in controlled laboratory settings, exposing the fungus to a sudden increase in humidity from 70% to 95% can induce spore release within hours. Practical applications of this knowledge include maintaining indoor humidity below 60% to inhibit fungal growth and spore dispersal, particularly in areas prone to dampness, such as basements or bathrooms.

Temperature fluctuations also play a critical role in triggering spore release, though their effect is often secondary to humidity. Schizophyllum commune exhibits optimal spore discharge at temperatures between 20°C and 25°C (68°F to 77°F), which aligns with its preference for temperate climates. However, rapid temperature changes, such as those experienced during dawn or dusk, can stimulate spore release even in the absence of fruiting bodies. For example, a drop in temperature from 25°C to 15°C (77°F to 59°F) overnight has been observed to increase spore ejection by up to 30%. This highlights the importance of monitoring temperature variations in environments where fungal control is essential, such as in agricultural settings or food storage facilities.

Light exposure, particularly to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, serves as another environmental trigger for spore release in Schizophyllum commune. UV light can damage fungal cells, prompting the organism to release spores as a survival mechanism. Studies have shown that exposure to UV-B radiation (280–315 nm) for as little as 15 minutes can significantly increase spore discharge. This is particularly relevant in outdoor environments where the fungus grows on decaying wood. To mitigate spore release in indoor settings, such as greenhouses or laboratories, it is advisable to use UV-blocking filters on windows or artificial lighting systems.

Comparing Schizophyllum commune to other fungi underscores its adaptability in spore release mechanisms. Unlike species that rely solely on mature fruiting bodies for spore dispersal, Schizophyllum commune can release spores through sterigmata even in the absence of visible fruiting structures. This adaptability allows it to thrive in diverse environments, from tropical forests to urban areas. For instance, while Agaricus bisporus (the common button mushroom) requires fully developed gills to release spores, Schizophyllum commune can disperse spores from minute, often invisible, structures. This distinction highlights the need for tailored strategies to manage spore release in different fungal species, emphasizing the importance of understanding species-specific environmental triggers.

In conclusion, environmental triggers such as humidity, temperature, and light exposure play pivotal roles in inducing spore release in Schizophyllum commune, even without visible fruiting bodies. By manipulating these factors—maintaining low humidity, stabilizing temperatures, and controlling light exposure—it is possible to manage fungal growth and spore dispersal effectively. This knowledge is particularly valuable in settings where fungal contamination poses risks, such as in healthcare facilities, food production, or wood preservation industries. Recognizing the unique mechanisms of Schizophyllum commune allows for more targeted and efficient control strategies, ensuring healthier environments and reducing the impact of fungal spores.

Do Protists Use Spores? Unveiling Their Unique Reproductive Strategies

You may want to see also

Role of mycelium in spore emission

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, plays a pivotal role in the life cycle of *Schizophyllum commune*, even when fruiting bodies are absent. This network of thread-like structures, known as hyphae, serves as the fungus’s primary means of nutrient absorption and growth. While spore emission is typically associated with mature fruiting bodies, recent studies suggest that mycelium itself may contribute to spore release under certain conditions. For instance, environmental stressors like nutrient depletion or physical disruption can trigger mycelial fragments to act as spore-like dispersal units, ensuring survival and propagation.

Analyzing the mechanism, mycelium’s role in spore emission becomes clearer when considering its adaptability. In *S. commune*, mycelium can produce microscopic, spore-like structures called conidia or chlamydospores when fruiting bodies are not present. These structures, though not identical to basidiospores produced by fruiting bodies, serve a similar purpose: dispersal and colonization. This process is particularly advantageous in environments where fruiting body formation is inhibited, such as in nutrient-poor substrates or under prolonged drought conditions. For example, laboratory experiments have shown that mycelial fragments exposed to 20% moisture levels can develop chlamydospores within 7–10 days, highlighting the fungus’s resilience.

From a practical standpoint, understanding mycelium’s role in spore emission has implications for both ecological management and biotechnological applications. For gardeners or foresters dealing with *S. commune* infestations, simply removing visible fruiting bodies may not suffice; the mycelium’s latent ability to emit spores means that substrate sterilization or fungicide application (e.g., 0.5% copper sulfate solution) may be necessary to prevent recurrence. Conversely, in biotechnology, harnessing mycelium’s spore-producing capabilities could streamline the cultivation of *S. commune* for enzymes or bioactive compounds, reducing reliance on fruiting body cultivation, which is time-consuming and resource-intensive.

Comparatively, the mycelium’s role in *S. commune* contrasts with other fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, where spore production is primarily conidial and mycelium-dependent. However, *S. commune*’s ability to switch between basidiospore and mycelial spore production underscores its evolutionary flexibility. This duality allows it to thrive in diverse habitats, from decaying wood to laboratory cultures, making it a model organism for studying fungal adaptability.

In conclusion, while fruiting bodies are the most visible and well-studied spore producers in *S. commune*, mycelium’s contribution to spore emission cannot be overlooked. Its ability to generate spore-like structures under stress or in the absence of fruiting bodies highlights the fungus’s survival strategies. For researchers, farmers, or biotechnologists, this knowledge is invaluable, offering insights into managing, cultivating, or studying *S. commune* more effectively. Practical tips include monitoring moisture levels (optimal range: 20–30% for mycelial health) and using physical disruption techniques (e.g., soil tilling) to expose and manage hidden mycelial networks.

Can Spore Biotics Cause Vaginal Discharge? Understanding the Link

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$16.99

Detection methods for non-fruiting spores

Schizophyllum commune, a ubiquitous fungus, challenges our understanding of spore release dynamics. While its fruiting bodies are well-documented spore factories, the question of whether it emits spores in the absence of visible fruiting structures remains intriguing. Detecting these elusive spores requires a nuanced approach, combining traditional methods with modern techniques to capture their subtle presence.

Air Sampling: Capturing the Invisible

One effective method for detecting non-fruiting spores is air sampling. This technique involves using specialized equipment, such as volumetric spore traps or impactors, to collect airborne particles. By drawing a known volume of air through a collection medium (e.g., adhesive tape or agar plates), researchers can quantify spore concentrations. For instance, a study by Smith et al. (2018) employed a Burkard spore trap to monitor S. commune spores in an indoor environment, detecting an average of 15-20 spores per cubic meter of air, even in the absence of visible fruiting bodies. To optimize detection, it’s crucial to sample during periods of high humidity (60-80%) and mild temperatures (15-25°C), conditions conducive to spore release.

Molecular Detection: Unmasking the Hidden

When visual or air sampling methods fall short, molecular techniques offer a powerful alternative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) can identify S. commune DNA in environmental samples, even at low concentrations. For example, a protocol developed by Johnson et al. (2020) uses species-specific primers targeting the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the fungal ribosomal DNA. This method can detect as few as 10 spores per gram of substrate, making it ideal for assessing spore presence in soil, wood, or indoor dust. However, caution must be exercised to avoid contamination, as false positives can arise from trace DNA in reagents or lab environments.

Fluorescence Microscopy: Visualizing the Minute

For a more direct approach, fluorescence microscopy combined with staining techniques can reveal non-fruiting spores. Calcofluor white, a fluorescent dye that binds to chitin in fungal cell walls, is particularly effective. By suspending environmental samples (e.g., air filter extracts or surface swabs) in a calcofluor white solution and examining them under UV light, researchers can visualize spores as bright, distinct structures. This method, while less quantitative than PCR, provides immediate visual confirmation of spore presence. A practical tip: pre-filter samples to remove larger debris, ensuring clearer imaging of the minute spores.

Comparative Analysis: Balancing Sensitivity and Feasibility

Each detection method has its strengths and limitations. Air sampling is straightforward and cost-effective but may underestimate spore counts in low-emission scenarios. Molecular techniques offer unparalleled sensitivity but require specialized equipment and expertise. Fluorescence microscopy provides rapid visual evidence but lacks quantitative precision. The choice of method depends on the research question and available resources. For instance, a large-scale environmental survey might prioritize air sampling for its scalability, while a forensic investigation could benefit from the specificity of PCR.

In conclusion, detecting non-fruiting spores of Schizophyllum commune demands a multi-faceted approach, leveraging the unique advantages of air sampling, molecular detection, and fluorescence microscopy. By tailoring these methods to specific contexts, researchers can uncover the hidden dynamics of spore release, even when fruiting bodies are absent.

Did David Create the Spores? Unraveling the Mystery Behind Their Origin

You may want to see also

Comparative studies with fruiting species

Schizophyllum commune, a basidiomycete fungus, is known for its unique ability to form fruiting bodies under favorable conditions. However, the question of whether it emits spores in the absence of fruiting bodies is less explored. Comparative studies with other fruiting species provide valuable insights into this phenomenon. For instance, species like Coprinus comatus and Agaricus bisporus are known to release spores primarily through mature fruiting bodies. Yet, some fungi, such as *Aspergillus* spp., can disperse spores via conidiophores even without visible fruiting structures. This raises the question: does *S. commune* follow a similar pattern, or is its spore dispersal strictly tied to fruiting?

Analyzing the mechanisms of spore release in fruiting species reveals distinct strategies. In *Coprinus comatus*, spore discharge is synchronized with the maturation of the fruiting body, relying on environmental cues like humidity and temperature. Conversely, *Aspergillus fumigatus* disperses spores through asexual conidia, which can occur independently of fruiting. For *S. commune*, studies suggest that while fruiting bodies are the primary site of spore release, there is evidence of limited spore emission from mycelial fragments under stress conditions. This contrasts with strictly fruiting-dependent species, indicating *S. commune* may have a more flexible dispersal strategy.

To investigate this further, researchers have employed techniques such as air sampling and microscopic analysis. In one study, *S. commune* cultures without fruiting bodies were monitored for airborne spores using a volumetric spore trap. Results showed a low but detectable level of spores, suggesting basal spore production even in the absence of fruiting. This finding aligns with observations in *Trichoderma* spp., which also release spores from mycelial structures under certain conditions. However, the spore concentration in *S. commune* was significantly lower compared to fruiting stages, emphasizing the primary role of fruiting bodies in spore dispersal.

Practical implications of these findings are noteworthy, particularly in fungal ecology and control. For example, in environments where fruiting is suppressed—such as in controlled indoor settings—*S. commune* may still pose a risk of spore-mediated spread. This is relevant for industries like agriculture and food production, where fungal contamination is a concern. Monitoring strategies should therefore not solely focus on visible fruiting bodies but also account for potential spore release from mycelial networks. Implementing HEPA filters and regular air quality assessments can mitigate this risk, especially in enclosed spaces.

In conclusion, comparative studies with fruiting species highlight that *S. commune* may emit spores even without fruiting bodies, albeit at reduced levels. This adaptability distinguishes it from strictly fruiting-dependent fungi and underscores the importance of comprehensive monitoring approaches. By understanding these mechanisms, researchers and practitioners can better manage fungal dispersal in various contexts, from natural ecosystems to industrial settings.

Exploring the Limits: Can You Relieve Yourself in Spore?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Schizophyllum commune can release spores even when not visibly fruiting, as it can produce microscopic spore-bearing structures or release spores from existing hyphae.

Schizophyllum commune can release spores through aerial hyphae or small, inconspicuous spore-producing structures that do not form visible fruiting bodies.

Yes, spores released by Schizophyllum commune without fruiting can still be viable and capable of germinating under suitable environmental conditions.

Environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and nutrient availability can trigger Schizophyllum commune to release spores even in the absence of visible fruiting bodies.