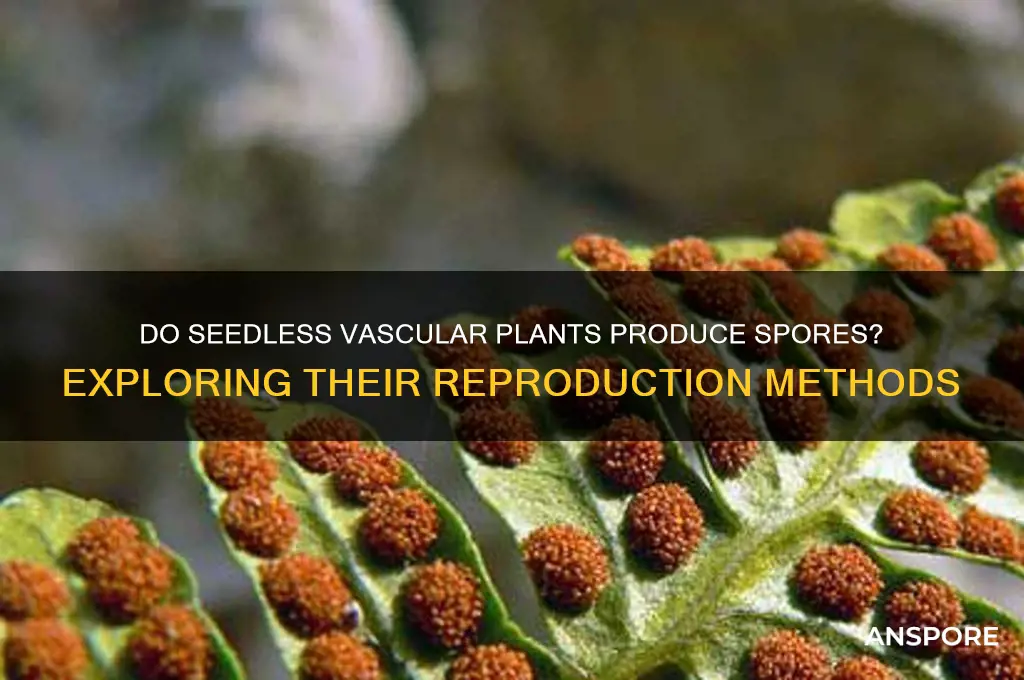

Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses, reproduce via spores rather than seeds. These plants, which belong to the division Pteridophyta, lack flowers and seeds but possess specialized structures called sporangia where spores are produced. Spores are haploid, single-celled reproductive units that develop into gametophytes, the sexual phase of the plant's life cycle. Unlike seed plants, which protect their embryos with a seed coat and store nutrients, seedless vascular plants rely on spores to disperse and grow into new individuals under favorable conditions. This method of reproduction is a defining characteristic of these plants and highlights their evolutionary position as a bridge between non-vascular plants and more advanced seed-bearing species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Primarily reproduce via spores (sporophytes) |

| Spores | Present; produced in sporangia located on leaf-like structures or stems |

| Seeds | Absent; do not produce seeds |

| Vascular Tissue | Present (xylem and phloem for water and nutrient transport) |

| Examples | Ferns, horsetails, clubmosses, and whisk ferns |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations (sporophyte and gametophyte phases) |

| Gametophytes | Typically small, free-living, and dependent on moisture |

| Sporophytes | Dominant phase, vascularized, and long-lived |

| Habitat | Moist environments (e.g., forests, wetlands) |

| Evolutionary Significance | Among the earliest vascular plants, bridging non-vascular plants and seed plants |

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Alternation of Generations: Seedless vascular plants exhibit alternation between sporophyte and gametophyte generations

- Spore Production: Spores are produced in sporangia on the sporophyte generation

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

- Gametophyte Dependence: Gametophytes rely on moisture for survival and reproduction

- Evolutionary Significance: Spores are key to the evolution of seedless vascular plants

Alternation of Generations: Seedless vascular plants exhibit alternation between sporophyte and gametophyte generations

Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and horsetails, showcase a fascinating life cycle known as alternation of generations. This process involves the cyclical transition between two distinct phases: the sporophyte and the gametophyte. Each generation is morphologically and functionally unique, yet interconnected in a way that ensures the species' survival. The sporophyte, typically the more visible and dominant phase, produces spores through specialized structures like sporangia. These spores, in turn, develop into the gametophyte, a smaller, less conspicuous phase that focuses on sexual reproduction. This alternating pattern is a cornerstone of their reproductive strategy, allowing them to thrive in diverse environments.

To understand this alternation, consider the fern as a prime example. The fern we commonly see is the sporophyte generation, characterized by its fronds and root system. On the underside of these fronds, sori (clusters of sporangia) produce haploid spores through meiosis. When released, these spores germinate into a gametophyte, known as a prothallus, which is a small, heart-shaped structure. The prothallus houses both male (antheridia) and female (archegonia) reproductive organs. Fertilization occurs when sperm from the antheridia swim to an egg in the archegonium, resulting in a diploid zygote that grows into a new sporophyte. This cyclical process ensures genetic diversity and adaptability.

From a practical standpoint, understanding alternation of generations is crucial for horticulture and conservation. For instance, propagating ferns often involves cultivating spores rather than relying on seeds, as ferns lack seeds entirely. Gardeners can collect spores from mature fronds, sow them on a moist substrate, and maintain high humidity to encourage prothallus development. Once the gametophytes mature, fertilization can occur naturally, leading to the growth of new sporophytes. This method not only preserves genetic diversity but also allows for the cultivation of rare or endangered species.

Comparatively, seedless vascular plants differ from seed plants in their reliance on water for reproduction. While seed plants use pollen and seeds to disperse their offspring, seedless plants depend on spores and gametophytes, which require moisture for survival and fertilization. This distinction highlights the evolutionary adaptations of seedless vascular plants to their environments, often thriving in humid or aquatic habitats. For educators and students, this comparison provides a clear illustration of how reproductive strategies have diversified over evolutionary time.

In conclusion, the alternation of generations in seedless vascular plants is a remarkable biological phenomenon that balances complexity and efficiency. By alternating between sporophyte and gametophyte generations, these plants ensure genetic diversity, adaptability, and survival in varied ecosystems. Whether for scientific study, conservation efforts, or gardening, understanding this life cycle offers practical insights and a deeper appreciation for the intricacies of plant biology.

Are Spores Gram-Positive? Unraveling the Bacterial Classification Mystery

You may want to see also

Spore Production: Spores are produced in sporangia on the sporophyte generation

Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and horsetails, rely on spores for reproduction, a process deeply rooted in their life cycle. Unlike seed-producing plants, these species depend on sporangia—specialized structures located on the sporophyte generation—to produce and disperse spores. This mechanism ensures their survival and propagation in diverse environments, from lush forests to arid landscapes. Understanding spore production in sporangia is key to grasping how these plants thrive without seeds.

The sporophyte generation, the dominant phase in seedless vascular plants, is where sporangia develop. These structures are typically found on the undersides of leaves or on modified stems, depending on the species. For example, ferns produce sporangia in clusters called sori, often visible as small dots on the leaf’s underside. Inside each sporangium, spores are formed through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number, creating haploid cells ready for dispersal. This step is critical, as it ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in the next generation.

Sporangia are not just spore factories; they are marvels of biological engineering. Their structure is designed to optimize spore release. In many plants, sporangia have a slit or opening that allows spores to be ejected into the air, often aided by environmental factors like wind or humidity. For instance, some fern sporangia have an annulus, a ring of cells that dries out and contracts, propelling spores outward. This mechanism ensures efficient dispersal, increasing the chances of spores reaching suitable habitats for germination.

Practical observation of spore production can be a rewarding experience. To witness this process, collect a mature fern frond with visible sori and place it in a dry, warm environment. Over time, you’ll notice a fine dust accumulating beneath the frond—these are the spores released from the sporangia. For educational purposes, magnifying tools can reveal the intricate structure of sporangia and spores, offering a tangible connection to the plant’s reproductive cycle.

In conclusion, spore production in sporangia on the sporophyte generation is a cornerstone of seedless vascular plant reproduction. This process combines precision, adaptability, and efficiency, ensuring the survival of these ancient plant groups. By studying sporangia, we gain insights into the evolutionary strategies that have allowed seedless vascular plants to flourish for millions of years, even in the absence of seeds.

Does Meiosis Occur in Fungi Spores? Exploring Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

Spores, the microscopic units of reproduction in seedless vascular plants, rely on external forces for dispersal to ensure colonization in new habitats. Wind, the most common agent, carries lightweight spores over vast distances, a strategy exemplified by ferns and lycophytes. These plants produce spores with structures like wings or air pockets, optimizing their aerodynamic potential. For instance, a single fern can release millions of spores, with wind currents dispersing them up to several kilometers, depending on atmospheric conditions. This method, while efficient, is largely passive, relying on environmental factors for success.

Water serves as another vital dispersal mechanism, particularly for plants in aquatic or riparian environments. Species like certain quillworts and some liverworts release spores that are buoyant, allowing them to float downstream or across water bodies. This method is highly effective in localized colonization, as water provides a direct pathway to suitable habitats. However, it is limited by the availability and flow of water, making it less universal than wind dispersal. For optimal results, plants in such environments often synchronize spore release with seasonal water flow patterns, increasing the likelihood of successful dispersal.

Animal-mediated dispersal, though less common, plays a unique role in spore colonization. Spores can adhere to the fur, feathers, or bodies of animals, hitchhiking to new locations. This method is particularly effective for plants in dense forests or shaded areas where wind and water dispersal are hindered. Mosses and some ferns benefit from this mechanism, as their spores are often sticky or have barbs that facilitate attachment. For instance, a deer grazing in a moss-rich area can inadvertently carry spores to distant sites, enabling colonization in otherwise inaccessible areas.

Each dispersal mechanism has its advantages and limitations, shaping the ecological niches seedless vascular plants occupy. Wind dispersal maximizes reach but lacks precision, while water dispersal ensures targeted colonization in specific environments. Animal-mediated dispersal bridges gaps between habitats, fostering genetic diversity. Understanding these mechanisms not only highlights the adaptability of seedless vascular plants but also informs conservation efforts, such as preserving wind corridors or maintaining water flow integrity in critical ecosystems. By leveraging these natural processes, we can support the resilience and spread of these ancient plant groups.

Metronome Spore's Sleep Clause Impact: Breaking the Rules or Fair Play?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gametophyte Dependence: Gametophytes rely on moisture for survival and reproduction

Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and lycophytes, produce spores as part of their life cycle, but their gametophytes—the haploid phase—are particularly vulnerable to desiccation. Unlike the sporophyte phase, which has vascular tissue to transport water, gametophytes lack this adaptive feature, making them critically dependent on moisture for survival and reproduction. This reliance on water is not just a minor inconvenience; it shapes their entire ecology, dictating where they can grow and how they reproduce.

Consider the fern gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that requires a consistently damp environment to thrive. Without adequate moisture, it cannot photosynthesize effectively or maintain cellular functions, leading to rapid deterioration. Reproduction is equally moisture-dependent: sperm from the antheridia must swim through a water film to reach the egg in the archegonia. This process, known as zoospore-mediated fertilization, is impossible in dry conditions. For gardeners or enthusiasts cultivating ferns, maintaining a humidity level of at least 60% and ensuring the substrate remains moist—but not waterlogged—is essential for gametophyte health.

This dependence on moisture also explains why seedless vascular plants are predominantly found in humid environments, such as rainforests or wetlands. In drier habitats, their gametophytes struggle to survive, limiting the species' distribution. For instance, the resurrection fern (*Pleopeltis polypodioides*) can tolerate desiccation in its sporophyte phase but still requires moisture for gametophyte development. This contrast highlights the gametophyte's unique vulnerability and its role as the bottleneck in the plant's life cycle.

From an evolutionary perspective, this moisture dependence is both a constraint and a driver of adaptation. While it restricts seedless vascular plants to specific habitats, it has also led to innovations like the protective structures of sporophytes and the development of spores, which can disperse and survive in drier conditions. However, the gametophyte phase remains a relic of earlier plant evolution, tethered to water in a way that seed plants have largely overcome.

For those studying or cultivating these plants, understanding gametophyte dependence on moisture is key. Practical tips include misting gametophytes daily, using a humidity tray, or growing them in terrariums to mimic their natural environment. By providing consistent moisture, you can observe the entire life cycle of these plants, from spore germination to the development of sporophytes. This not only enhances their survival but also offers a deeper appreciation of their ecological and evolutionary significance.

Mastering Spore Syringe Creation: A Step-by-Step DIY Guide

You may want to see also

Evolutionary Significance: Spores are key to the evolution of seedless vascular plants

Spores are the lifeblood of seedless vascular plants, serving as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. Unlike seeds, which contain a young plant protected by a seed coat, spores are single-celled reproductive units that develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. This simplicity in structure and function has been pivotal in the evolutionary success of seedless vascular plants, such as ferns, lycophytes, and horsetails. By producing vast quantities of spores, these plants ensure genetic diversity and increase their chances of colonizing new habitats, even in challenging environments.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a quintessential seedless vascular plant. After a spore germinates, it grows into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte, which is the sexual phase of the plant. This gametophyte produces eggs and sperm, which, when united, develop into the sporophyte—the familiar fern we recognize. The sporophyte then releases spores, restarting the cycle. This alternation of generations, made possible by spores, allows ferns to adapt rapidly to environmental changes. For instance, in moist, shaded areas, ferns thrive due to their efficient spore dispersal mechanisms, which rely on wind and water rather than animal pollinators.

From an evolutionary standpoint, spores represent a critical innovation that predates seeds by millions of years. They enabled early land plants to transition from aquatic environments to terrestrial ecosystems, as spores are lightweight, easily dispersed, and capable of surviving desiccation. This adaptability laid the foundation for the diversification of vascular plants, which later gave rise to seed plants. However, seedless vascular plants retained spores as their reproductive strategy, highlighting their effectiveness in specific ecological niches. For example, in tropical rainforests, where humidity is high, spore-producing plants dominate the understory, outcompeting seed plants in these conditions.

To understand the evolutionary significance of spores, compare them to seeds. While seeds are more complex and provide greater protection for the developing embryo, spores offer a different set of advantages. They are produced in larger numbers, require fewer resources, and can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This resilience makes spores ideal for plants in unpredictable environments, such as floodplains or disturbed habitats. For gardeners or conservationists working with seedless vascular plants, encouraging spore production through proper moisture and light conditions can enhance propagation success.

In conclusion, spores are not just a reproductive mechanism but a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of seedless vascular plants. Their role in ensuring survival, dispersal, and adaptation underscores their significance in the plant kingdom. By studying spores, we gain insights into the early stages of plant evolution and the strategies that have allowed certain species to persist for millions of years. Whether in a laboratory, garden, or natural habitat, understanding spores is key to appreciating the resilience and diversity of seedless vascular plants.

Does Ethylene Oxide Effectively Kill Spores? A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and horsetails, reproduce via spores as their primary method of reproduction.

Seedless vascular plants release spores that develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes (sperm and eggs). Fertilization occurs when sperm swims to the egg, forming a new sporophyte plant.

Yes, spores are the primary and often the only method of reproduction for seedless vascular plants, as they lack seeds or flowers for alternative reproductive strategies.