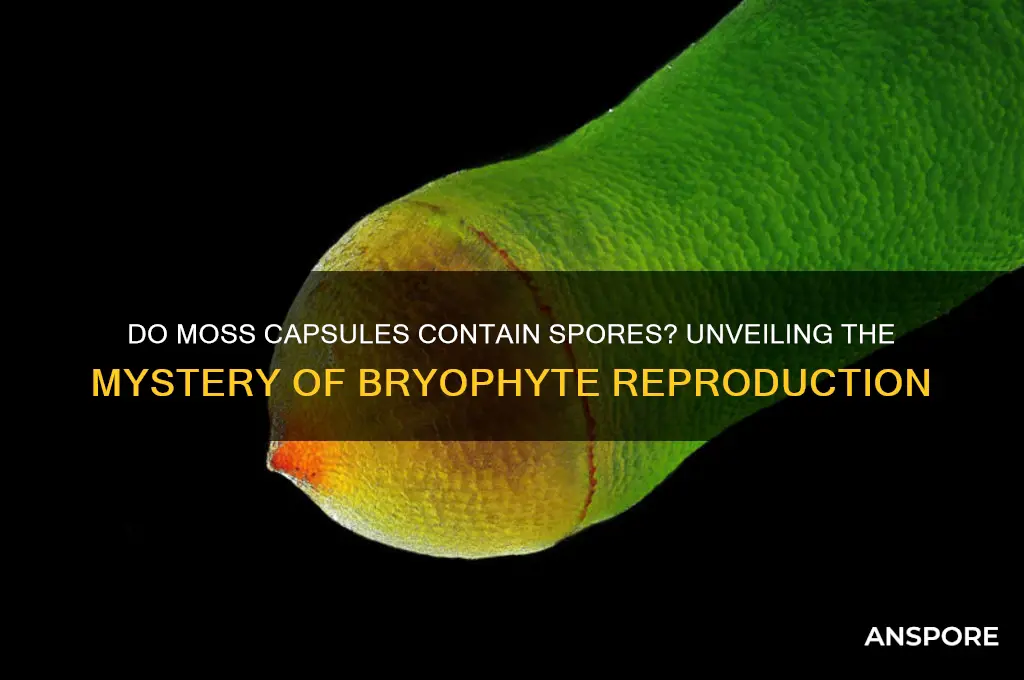

The capsule of mosses, a critical structure in their reproductive cycle, plays a significant role in the dispersal of spores. Mosses, as non-vascular plants, rely on this capsule, also known as a sporangium, to produce and release spores into the environment. The capsule is typically located at the tip of a slender stalk, known as a seta, which emerges from the moss plant. As the capsule matures, it undergoes a series of changes, including the development of a lid-like structure called an operculum, which eventually falls off, allowing the spores to be released. The question of whether the capsule of mosses contains spores is fundamental to understanding their life cycle, as the spores are essential for the propagation and survival of these primitive plants.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Presence of Spores | Yes, the capsule of mosses (sporangium) contains spores. |

| Function of Spores | Spores are the reproductive units used for dispersal and propagation. |

| Type of Spores | Haploid spores produced via meiosis in the sporophyte generation. |

| Capsule Structure | The capsule is a terminal structure on the seta (stalk) of the moss. |

| Capsule Opening | Capsules often have a lid (operculum) that falls off to release spores. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are released through the peristome, a ring of teeth-like structures. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are part of the alternation of generations in mosses (sporophyte phase). |

| Environmental Adaptation | Spores are lightweight and can be wind-dispersed to colonize new areas. |

| Capsule Shape | Capsules are typically elongated and cylindrical in shape. |

| Capsule Color | Color varies by species, often ranging from green to brown or red. |

| Capsule Protection | The capsule is often protected by a calyptra (a cap-like structure) during development. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Capsule Structure and Function: Examines the role of the capsule in spore development and dispersal

- Spore Formation Process: Details how spores are produced and stored within the moss capsule

- Capsule Opening Mechanism: Explains how capsules release spores into the environment for propagation

- Spore Viability and Dispersal: Assesses factors affecting spore survival and spread after capsule release

- Capsule vs. Sporophyte Relationship: Explores the connection between the capsule and the sporophyte generation in mosses

Capsule Structure and Function: Examines the role of the capsule in spore development and dispersal

The capsule of mosses, a critical structure in their life cycle, serves as the protective chamber where spores develop and mature. This organ, often perched atop a slender seta, is a marvel of botanical engineering, designed to ensure the survival and dispersal of the next generation. Its structure is not merely a passive container but an active participant in the reproductive process, influencing the timing and mechanism of spore release.

Consider the capsule’s anatomy: a cylindrical or spherical body, capped by an operculum, which acts as a lid. As the spores mature within, the capsule undergoes desiccation, creating tension that eventually leads to the operculum’s detachment. This mechanism, triggered by environmental cues like humidity changes, ensures spores are released under optimal conditions for dispersal. For instance, *Sphagnum* mosses have capsules that open via a toothed lid, allowing spores to be ejected with precision, often aided by wind or water.

To understand the capsule’s role in spore development, imagine it as a nursery. Inside, spores undergo meiosis, forming haploid cells ready for germination. The capsule’s walls provide a stable microenvironment, shielding spores from predators and harsh conditions. In *Polytrichum* mosses, the capsule’s thick, waxy cuticle prevents desiccation, ensuring spores remain viable until dispersal. This protective function is critical, as spores are the primary means of long-distance colonization for mosses, which lack true roots and vascular tissues.

Dispersal strategies vary, but the capsule’s design often dictates the method. Some capsules, like those in *Funaria*, dry out and split open, releasing spores in a passive manner. Others, such as *Sphagnum*, employ explosive mechanisms, launching spores meters into the air. Practical observation tip: to witness this, place a mature capsule under a microscope or on a dark surface and observe the spore cloud upon opening. This demonstrates how capsule structure directly influences dispersal efficiency, a key factor in mosses’ ability to colonize diverse habitats.

In conclusion, the capsule is not just a spore container but a dynamic organ that orchestrates development and dispersal. Its structure—from the operculum to the elastic walls—is finely tuned to environmental cues, ensuring spores are released at the right time and in the right manner. For enthusiasts or researchers, studying capsule morphology across moss species provides insights into evolutionary adaptations and ecological strategies. By examining these structures, we uncover the intricate ways mosses thrive in their environments, highlighting the capsule’s indispensable role in their life cycle.

Regrowing Fungi with Spore Prints: A Comprehensive Guide to Success

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Process: Details how spores are produced and stored within the moss capsule

Mosses, unlike vascular plants, rely on spores for reproduction, and the capsule, or sporangium, is the epicenter of this process. Within this tiny, often spherical structure, a complex dance of cellular division and differentiation unfolds. The process begins with the fertilization of an egg by a sperm, typically facilitated by water, resulting in the formation of a diploid sporophyte. This sporophyte then grows atop the gametophyte (the green, leafy structure we commonly associate with moss) and develops the capsule where spores will be produced.

The production of spores within the moss capsule is a marvel of precision and efficiency. Inside the capsule, cells undergo meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spore mother cells. These cells then divide further through mitosis, giving rise to numerous spores. The capsule’s structure is designed to protect these spores during development, featuring a central columella (a supportive axis) and an outer wall that may thicken or develop specialized layers to withstand environmental stresses.

Storage of spores within the capsule is equally strategic. As spores mature, they accumulate at the capsule’s base, often surrounded by elaters—coiled, hygroscopic cells that aid in spore dispersal. The capsule’s apex, or operculum, acts as a lid, sealing the spores inside until optimal conditions for release arise. When mature, the operculum falls off, or the capsule splits open, releasing spores into the environment. This timing is crucial, as it ensures spores are dispersed when conditions favor germination and growth.

Practical observation of this process can be achieved by examining mature moss capsules under a microscope. Look for the columella and the arrangement of spores at the base. For enthusiasts, collecting moss samples in late summer or early fall increases the likelihood of observing mature capsules. Gently pressing a capsule onto a slide can reveal the spores and elaters, offering a firsthand glimpse into this intricate reproductive mechanism. Understanding this process not only deepens appreciation for moss biology but also highlights the adaptability of non-vascular plants in diverse ecosystems.

Do Spores Thrive Inside Flowers? Unveiling the Hidden Botanical Mystery

You may want to see also

Capsule Opening Mechanism: Explains how capsules release spores into the environment for propagation

The capsule of mosses, a critical structure in their life cycle, houses the spores responsible for propagation. But how do these capsules release their precious cargo into the environment? The answer lies in a sophisticated yet elegant mechanism that combines anatomical precision with environmental responsiveness. This process, known as dehiscence, ensures that spores are dispersed efficiently, maximizing the chances of colonization in new habitats.

Consider the capsule’s structure: it is typically elongated and capped by a lid-like structure called the operculum. As the capsule matures, it accumulates desiccation-induced tension in its walls, particularly in the exothecial layer, which acts as a hygroscopic tissue. When environmental conditions—such as humidity or dryness—reach a threshold, this tissue responds by shrinking or swelling. The resulting mechanical stress causes the operculum to separate from the capsule, exposing the spore-filled interior. This mechanism is akin to a spring-loaded trap, releasing spores in a burst that can be carried by wind or water.

To visualize this, imagine a tiny, pressurized vessel primed for release. The operculum acts as a seal, and the exothecial layer as the trigger. When activated, the capsule splits open along predefined lines of dehiscence, often spiraling or longitudinal, allowing spores to escape in a controlled yet dynamic manner. This process is not random; it is finely tuned to environmental cues, ensuring spores are released when conditions are optimal for germination and growth.

Practical observation of this mechanism can be enhanced by examining mature moss capsules under a microscope. Look for signs of drying or swelling in the capsule walls, which indicate the tissue is preparing for dehiscence. Gently manipulating humidity levels around the moss can accelerate the process, providing a real-time demonstration of how environmental factors drive spore release. For educators or enthusiasts, this experiment offers a tangible way to illustrate the interplay between plant anatomy and ecology.

In conclusion, the capsule opening mechanism in mosses is a marvel of evolutionary engineering. By harnessing environmental triggers and anatomical precision, mosses ensure their spores are dispersed effectively, perpetuating their species across diverse ecosystems. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation for moss biology but also highlights the ingenuity of nature’s solutions to propagation challenges.

Unveiling the Spore-Producing Structures: A Comprehensive Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.24 $16.75

Spore Viability and Dispersal: Assesses factors affecting spore survival and spread after capsule release

Moss capsules, those tiny, often spherical structures atop moss plants, are not just decorative features but vital spore-bearing organs. Each capsule contains countless spores, the microscopic units of life that ensure the species' survival and propagation. However, the journey from capsule to new moss plant is fraught with challenges. Spore viability and dispersal are critical factors that determine whether these spores will successfully germinate and establish new colonies. Understanding these factors is essential for both ecological research and practical applications like moss cultivation.

Environmental conditions play a pivotal role in spore survival. Humidity, temperature, and light exposure directly impact spore viability. For instance, spores of *Sphagnum* mosses, commonly found in peatlands, require high humidity levels to remain viable. In contrast, spores of *Polytrichum* mosses, which inhabit drier environments, are more tolerant of desiccation. Temperature fluctuations can also affect spore longevity; extreme heat or cold can reduce viability, with optimal germination often occurring between 15°C and 25°C. To maximize spore survival, collectors and researchers should store spores in cool, dark, and humid conditions, mimicking their natural environment.

Dispersal mechanisms are equally crucial for spore spread. Mosses rely on wind, water, and even animals for dispersal, but the effectiveness of these methods varies. Wind dispersal, common in species like *Bryum argenteum*, depends on capsule structure and spore size. Smaller, lighter spores travel farther but may be more susceptible to environmental stressors. Water dispersal, seen in aquatic mosses like *Fontinalis antipyretica*, ensures spores reach suitable habitats but limits their range. Enhancing dispersal in cultivation settings can be achieved by placing mosses in elevated, open areas to catch wind currents or by gently misting spores onto target surfaces.

Human intervention can further optimize spore viability and dispersal. For moss gardening, applying a thin layer of sterile soil or peat moss to the substrate before spore dispersal can improve germination rates. Additionally, using a fine mist spray to simulate dew can create the moisture conditions spores need to thrive. In research settings, controlled environments like growth chambers allow scientists to manipulate variables like humidity and light, providing insights into optimal conditions for spore survival. Practical tips include monitoring spore release times, as many mosses discharge spores in the morning, and avoiding handling capsules directly to prevent contamination.

Ultimately, the interplay of environmental factors, dispersal mechanisms, and human intervention shapes the fate of moss spores. By understanding these dynamics, enthusiasts and researchers can foster healthier moss populations, whether in natural ecosystems or cultivated settings. For example, conservation efforts for endangered moss species could focus on creating microhabitats that enhance spore viability, while gardeners can employ targeted dispersal techniques to establish lush moss carpets. The key lies in respecting the delicate balance between nature and nurture, ensuring that these tiny spores have the best chance to grow into thriving moss communities.

Exploring the Soft Outer Coating of Spores: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Capsule vs. Sporophyte Relationship: Explores the connection between the capsule and the sporophyte generation in mosses

The capsule in mosses, often referred to as the sporangium, is a critical structure in the life cycle of these non-vascular plants. It is here that the sporophyte generation develops, a phase that starkly contrasts with the more familiar gametophyte generation. While the gametophyte is the dominant, long-lived stage in mosses, the sporophyte is short-lived and entirely dependent on the gametophyte for nutrition. The capsule, perched atop a slender seta, is not merely a container but a dynamic site of spore production, highlighting the intricate relationship between these two generations.

To understand this relationship, consider the capsule as a factory where spores are manufactured. Inside the capsule, sporophyte tissue undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, which will eventually grow into new gametophytes. This process is a delicate balance of dependency: the sporophyte relies on the gametophyte for water, nutrients, and structural support, while the gametophyte depends on the sporophyte to produce the next generation. The capsule’s structure, with its peristome teeth or other mechanisms, ensures spore dispersal, a critical step in the moss life cycle.

A practical example illustrates this connection: *Sphagnum* moss, widely used in horticulture, showcases this sporophyte-capsule relationship vividly. Its capsule, when mature, dries and splits open, releasing spores into the wind. Gardeners cultivating *Sphagnum* must ensure high humidity and indirect light to support both gametophyte and sporophyte stages. For instance, maintaining a humidity level of 60-70% and avoiding direct sunlight fosters healthy capsule development, crucial for spore production.

However, the capsule-sporophyte relationship is not without challenges. Environmental stressors like drought or pollution can disrupt capsule maturation, leading to reduced spore viability. In laboratory settings, researchers often simulate optimal conditions—controlled humidity, temperature, and light—to study this relationship. For hobbyists, replicating these conditions using a terrarium with a misting system can enhance success in observing spore release.

In conclusion, the capsule and sporophyte generation in mosses are intertwined in a symbiotic dance of survival and reproduction. By understanding this relationship, enthusiasts and researchers alike can better cultivate and study these fascinating plants. Practical steps, such as maintaining optimal humidity and light, ensure the capsule functions effectively, bridging the gap between generations in the moss life cycle.

Are Mold Spores Invisible? Unveiling the Hidden Truth About Mold

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the capsule of mosses, also known as the sporangium, contains spores that are produced as part of the moss's reproductive cycle.

Spores are released from the moss capsule through a small opening called the peristome, which opens and closes in response to changes in humidity, allowing spores to be dispersed by wind or water.

Spores in mosses serve as the primary means of asexual reproduction, allowing mosses to disperse and colonize new environments. Each spore can develop into a new moss plant under suitable conditions.