The St. George's mushroom, scientifically known as *Calocybe gambosa*, is a springtime fungus traditionally associated with Europe, where it is often found in grassy areas and woodlands. Named for its typical appearance around St. George's Day (April 23), this mushroom has sparked curiosity among mycologists and foragers alike. While it is well-documented in Europe, questions arise about its presence in North America. Some reports suggest that *Calocybe gambosa* may indeed grow in certain regions of North America, particularly in the northeastern United States and parts of Canada, where environmental conditions resemble those of its European habitats. However, its occurrence in North America is less common and often debated, with misidentifications and limited documentation complicating the picture. Exploring whether the St. George's mushroom truly thrives in North America requires careful examination of ecological factors, historical records, and recent findings.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Calocybe gambosa |

| Common Name | St. George's Mushroom |

| Native Range | Europe, particularly the British Isles |

| Growth in North America | Yes, but less common and primarily in specific regions |

| Preferred Habitat | Grasslands, lawns, and pastures with calcareous (chalky) soil |

| Season | Spring, typically around St. George's Day (April 23) |

| Edibility | Edible, but must be cooked thoroughly to avoid digestive issues |

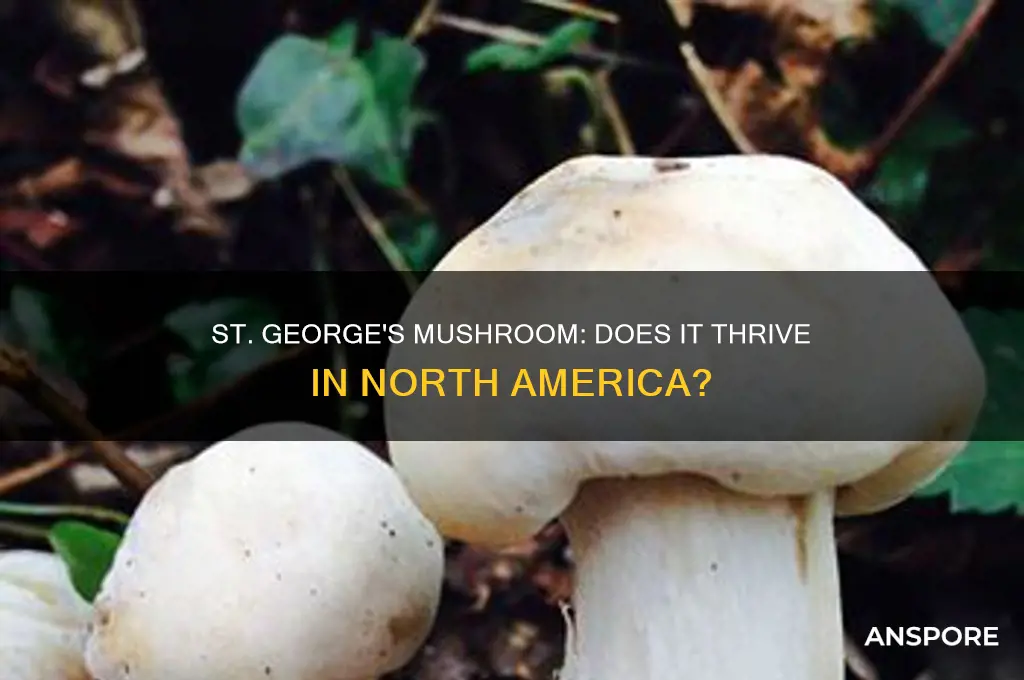

| Distinct Features | White to cream-colored cap, dense flesh, and a mealy smell |

| Conservation Status | Not globally threatened, but habitat loss is a concern |

| North American Distribution | Limited to areas with suitable soil conditions, e.g., parts of Canada and the northeastern U.S. |

| Mycorrhizal Association | No, saprotrophic (decomposes organic matter) |

| Cultural Significance | Named after St. George's Day due to its seasonal appearance |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Natural Habitat of St George's Mushroom

The St. George's mushroom, scientifically known as *Calocybe gambosa*, is a springtime delicacy that has intrigued foragers and mycologists alike. While it is traditionally associated with Europe, particularly the British Isles, its presence in North America is a topic of interest and some debate. The natural habitat of this mushroom is closely tied to specific environmental conditions, which helps explain its distribution across different regions.

In its native European range, *Calocybe gambosa* is commonly found in grassy areas such as meadows, pastures, and lawns, often near deciduous trees like oak and beech. It thrives in calcareous (chalky or lime-rich) soils, which are a defining feature of its habitat. The mushroom typically fruits in the spring, around St. George's Day (April 23), hence its common name. These environmental preferences—calcareous soil, grassy habitats, and a temperate climate—are key to understanding where it might grow in North America.

In North America, the St. George's mushroom is less commonly documented but has been reported in certain regions with similar ecological conditions. It is occasionally found in the northeastern United States and parts of Canada, particularly in areas with calcareous soils and grassy habitats. For example, limestone-rich regions in states like New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio have yielded sightings of this mushroom. However, its presence in North America is not as widespread or well-established as in Europe, likely due to differences in soil composition and land use practices.

Foraging for *Calocybe gambosa* in North America requires careful attention to habitat characteristics. Look for open, grassy areas with calcareous soil, often near deciduous woodlands or in regions with a history of limestone geology. Spring is the prime time to search, as the mushroom fruits in cooler temperatures before the onset of summer. While it is not as commonly encountered as other spring mushrooms like morels, its distinct appearance—white to cream-colored caps and a mealy smell—makes it identifiable for experienced foragers.

In conclusion, the natural habitat of the St. George's mushroom in North America mirrors its European preferences: grassy, calcareous environments in temperate regions. While it is not as prevalent in North America, its presence in specific areas highlights the importance of understanding local ecology and soil conditions. For those interested in finding this mushroom, focusing on limestone-rich regions during the spring months is the best approach. Always exercise caution and ensure proper identification, as some white-capped mushrooms can be toxic.

Mastering Commercial Mushroom Cultivation: A Comprehensive Guide to Profitable Growth

You may want to see also

North American Fungal Diversity

The St. George's mushroom is not native to North America, and its growth on the continent is limited and localized. Reports of *Calocybe gambosa* in North America are rare, with occasional sightings in the northeastern United States and parts of Canada. These occurrences are often attributed to accidental introductions, such as the mushroom's spores being transported through human activity or imported plant material. Unlike its widespread distribution in Europe, the St. George's mushroom does not thrive in North American ecosystems due to differences in climate, soil composition, and the absence of specific ecological conditions it requires.

Despite the rarity of *Calocybe gambosa* in North America, its occasional presence highlights the broader theme of fungal introductions and adaptations. North America's fungal diversity is influenced by both native species and introduced varieties, creating a dynamic and ever-evolving mycological landscape. Native fungi, such as the iconic *Amanita muscaria* (fly agaric) and the edible *Morchella* (morel) species, dominate the continent's forests and fields. However, the accidental or intentional introduction of non-native fungi, like the St. George's mushroom, underscores the interconnectedness of global ecosystems and the impact of human activity on biodiversity.

Exploring North American fungal diversity requires an understanding of regional variations and ecological niches. For instance, the Pacific Northwest is home to a vast array of fungi, including the prized *Cantharellus cibarius* (chanterelle) and the bioluminescent *Mycena lux-coeli*. In contrast, the southeastern United States boasts unique species like the *Clitocybe nuda* (wood blewit) and the *Lactarius indigo* (indigo milk cap). These regional differences are shaped by factors such as temperature, humidity, and vegetation, which collectively influence fungal growth and distribution. The occasional appearance of the St. George's mushroom in this diverse landscape serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between native and introduced species.

For those interested in studying North American fungal diversity, field guides, mycological societies, and citizen science initiatives are invaluable resources. Organizations like the North American Mycological Association (NAMA) provide platforms for education, research, and conservation efforts. Additionally, DNA sequencing and modern taxonomic tools have revolutionized the identification and classification of fungi, enabling scientists to better understand the relationships between species, including rare introductions like *Calocybe gambosa*. By fostering a deeper appreciation for fungi, we can contribute to the preservation of North America's unique mycological heritage.

In conclusion, while the St. George's mushroom is not a native or widespread species in North America, its occasional presence adds an intriguing layer to the continent's fungal diversity. North America's rich mycological tapestry is shaped by native species, regional variations, and the occasional introduction of non-native fungi. Studying this diversity not only enhances our understanding of ecosystems but also underscores the importance of conservation and responsible human interaction with the natural world. Whether you're a seasoned mycologist or a curious beginner, exploring North American fungi offers endless opportunities for discovery and learning.

DIY Mushroom Growing Guide for Minnesota Enthusiasts

You may want to see also

Climate Conditions for Growth

The St. George's mushroom (*Calocybe gambosa*), named for its typical appearance around St. George's Day (April 23rd), is a springtime delicacy found primarily in Europe. While it is not native to North America, there have been sporadic reports and discussions about its potential presence in certain regions of the continent. For this mushroom to grow, specific climate conditions must be met, mirroring its native European habitat. Understanding these conditions is crucial for determining whether it can thrive in North America.

Temperature Requirements: St. George's mushroom is a cool-weather species, favoring temperatures between 5°C and 15°C (41°F and 59°F). This temperature range aligns with the early spring conditions in its native habitats, such as the British Isles and parts of continental Europe. In North America, regions with similar spring climates, such as the Pacific Northwest, New England, and parts of the upper Midwest, could theoretically support its growth. Frost tolerance is another key factor, as the mushroom often emerges after the last frosts of winter, benefiting from the gradual warming of the soil.

Moisture and Humidity: Adequate moisture is essential for the growth of St. George's mushroom. It thrives in environments with consistent rainfall or high humidity, particularly during its fruiting period in spring. In North America, areas with maritime climates, such as coastal regions of the Pacific Northwest and the northeastern United States, provide the necessary moisture levels. However, excessive rain or waterlogged soil can hinder growth, so well-draining soil is also important. The mushroom often appears in grassy areas, pastures, and woodlands, where moisture retention is balanced with proper drainage.

Soil and Substrate: The mushroom prefers neutral to slightly alkaline soils, rich in organic matter. In Europe, it is commonly found in calcareous grasslands, which are characterized by chalky or limestone-rich soils. In North America, similar soil conditions can be found in certain limestone-rich areas, such as parts of the Appalachian Mountains and the Great Lakes region. The presence of grass or herbaceous vegetation is also critical, as the mushroom forms mycorrhizal associations with these plants. Without the appropriate soil pH and substrate, the mushroom is unlikely to establish itself.

Light and Seasonal Timing: St. George's mushroom is not shade-tolerant and requires ample sunlight, typically growing in open or semi-open habitats. This preference for light aligns with its springtime fruiting, when sunlight is abundant but not yet intense. In North America, regions with distinct seasons and a clear spring period are more likely to support its growth. The timing of spring warming and rainfall is particularly important, as the mushroom’s life cycle is tightly linked to these seasonal cues. Areas with prolonged winters or early springs may disrupt its growth cycle.

Geographic and Ecological Considerations: While the climate conditions in certain North American regions may mimic those of the St. George's mushroom’s native habitat, its presence remains unconfirmed in most areas. The mushroom’s mycorrhizal relationship with specific grasses and herbs may limit its ability to colonize new territories without the presence of these partner plants. Additionally, ecological factors such as competition from native fungi and changes in land use could further restrict its growth. For enthusiasts and mycologists interested in cultivating or finding this mushroom in North America, focusing on regions with the aforementioned climate conditions and conducting thorough ecological surveys would be the most productive approach.

Can Coffee Grounds Boost Mushroom Growth? A Gardening Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Geographical Distribution Patterns

The St. George's mushroom, scientifically known as *Calocybe gambosa*, is a species primarily associated with Europe, where it is commonly found in grasslands, meadows, and woodland edges. Its distribution is closely tied to temperate climates and specific ecological conditions, such as calcareous soils. While Europe is its well-documented habitat, the question of whether it grows in North America requires careful examination of geographical distribution patterns and ecological adaptability.

In North America, the presence of *Calocybe gambosa* is not as widely reported or confirmed as in Europe. The geographical distribution patterns of fungi are often influenced by factors such as climate, soil type, and historical migration routes. North America and Europe share similar temperate zones, but differences in soil composition, vegetation, and historical land connections may limit the mushroom's ability to establish itself in North American ecosystems. However, there have been sporadic reports and sightings of St. George's mushroom in certain regions of North America, particularly in areas with environmental conditions resembling its European habitats.

The sporadic occurrences of *Calocybe gambosa* in North America suggest that while it is not a widespread species in the continent, it may have been introduced or naturally migrated to specific locales. Geographical distribution patterns of fungi can be influenced by human activities, such as the transport of soil or plant material, which could explain its presence in isolated areas. Additionally, mycorrhizal relationships and symbiotic associations with local plant species may play a role in its limited establishment in North America.

To better understand the geographical distribution patterns of the St. George's mushroom in North America, further research and citizen science efforts are needed. Documenting sightings, analyzing soil and climate conditions, and studying potential mycorrhizal partners can provide insights into its adaptability and range. While it is not a dominant species in North America, its presence highlights the complex interplay between ecology, climate, and historical factors in shaping fungal distributions across continents.

In conclusion, the St. George's mushroom's geographical distribution patterns indicate a strong European focus, with limited and localized occurrences in North America. These patterns are shaped by ecological preferences, historical migration, and human influence. While it is not a common species in North America, its presence in specific regions underscores the importance of continued study to fully understand its distribution and adaptability in diverse environments.

Could I Be Allergic to the Mushrooms Growing in My Home?

You may want to see also

Identification and Look-Alike Species

The St. George's mushroom, scientifically known as *Calocybe gambosa*, is a springtime delicacy primarily found in Europe, particularly in the British Isles. While it is not native to North America, there have been occasional reports of similar-looking species in certain regions. Identifying *Calocybe gambosa* accurately is crucial, as it has several look-alike species, some of which are toxic or inedible. Below is a detailed guide to identification and distinguishing it from its North American counterparts.

Identification of *Calocybe gambosa*: This mushroom typically appears in spring, often around St. George's Day (April 23), hence its name. It has a creamy white to pale yellow cap, 3–10 cm in diameter, which is convex when young and flattens with age. The gills are closely spaced, white, and often have a slightly decurrent attachment to the stem. The stem is sturdy, white, and 3–8 cm tall. The flesh is thick, white, and has a mild, nutty aroma. *Calocybe gambosa* grows in grassy areas, often in fairy rings, and is mycorrhizal with certain trees. In North America, it is not commonly found, but misidentifications often occur due to similar species.

Look-Alike Species in North America: One of the most common look-alikes is *Clitocybe clavipes*, also known as the club-footed clitocybe. It has a similar creamy cap but features a distinct club-shaped base and lacks the nutty aroma of *Calocybe gambosa*. Another species, *Clitopilus hobbyi*, has a slimy cap and grows in wood debris, making it easy to distinguish. *Lyophyllum decastes*, or the fried chicken mushroom, forms large clusters in grassy areas and has a more robust stem and milder flavor. *Tricholoma species*, such as *Tricholoma saponaceum*, have a soapy smell and often grow in wooded areas, unlike *Calocybe gambosa*.

Toxic Look-Alikes: One dangerous look-alike is *Clitocybe dealbata*, which contains muscarine toxins. It has a white cap and grows in grassy areas but lacks the nutty aroma and often has a more fragile stem. Another toxic species is *Entoloma lividum*, which has a grayish cap and pink spores, easily distinguishable from *Calocybe gambosa*'s white gills. Proper spore print analysis and microscopic examination are essential to avoid confusion.

Key Identification Features: To accurately identify *Calocybe gambosa* or its look-alikes, focus on habitat, aroma, spore color, and microscopic features. *Calocybe gambosa* grows in grassy areas, has a nutty scent, and produces white spores. Look-alikes often differ in one or more of these characteristics. For example, the club-shaped stem of *Clitocybe clavipes* or the soapy smell of *Tricholoma saponaceum* are immediate red flags. Always cross-reference multiple features and consult a field guide or expert when in doubt.

Discovering Lobster Mushrooms: Do They Thrive in Michigan's Forests?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the St George's mushroom (*Calocybe gambosa*) does grow in North America, particularly in the northeastern and midwestern regions of the United States and parts of Canada.

In North America, St George's mushrooms are commonly found in grassy areas, such as meadows, pastures, and lawns, often near deciduous trees like oak or beech.

The best time to find St George's mushrooms in North America is in the spring, typically around late April to early May, coinciding with the feast day of St. George (April 23).

Yes, St George's mushrooms are edible and considered a delicacy in North America. However, they can be confused with toxic species like *Clitocybe dealbata* or *Entoloma* species, so proper identification is crucial. Always consult a field guide or expert if unsure.