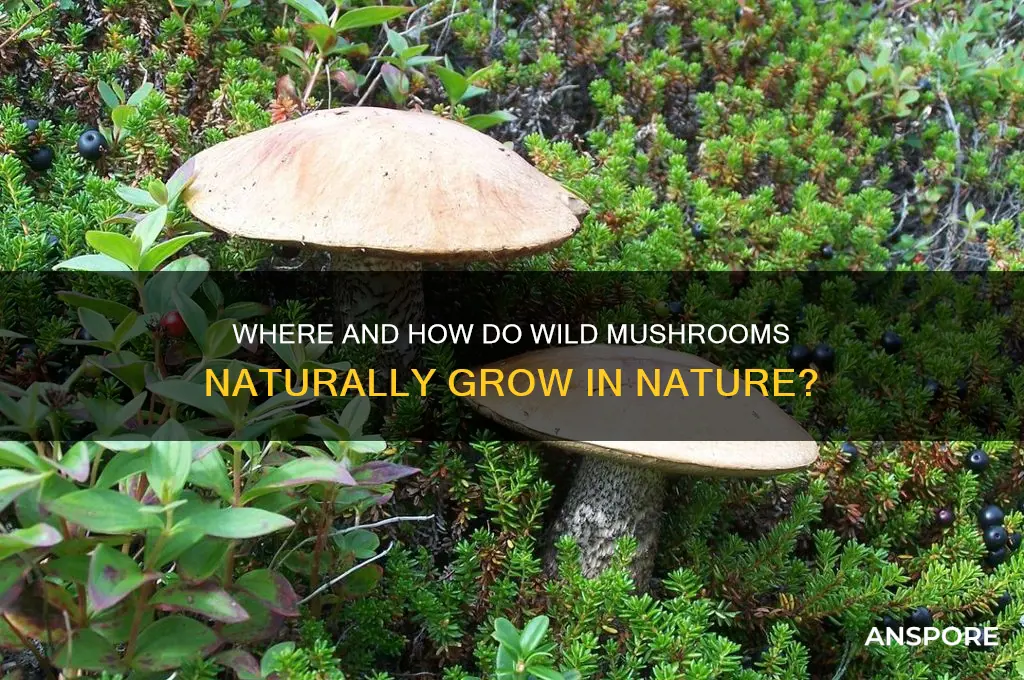

Wild mushrooms grow in a variety of environments, from dense forests and grassy meadows to decaying wood and soil rich in organic matter. Their growth is heavily influenced by factors such as moisture, temperature, and the presence of specific symbiotic relationships with plants or trees. Unlike cultivated mushrooms, which are grown in controlled conditions, wild mushrooms thrive in natural settings, often appearing after rainfall or during specific seasons. Identifying whether a mushroom is wild involves observing its habitat, structure, and characteristics, though caution is essential, as some wild mushrooms can be toxic or even deadly. Understanding where and how wild mushrooms grow not only highlights their ecological role but also underscores the importance of proper identification before foraging.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Growth Environment | Wild mushrooms grow in diverse environments, including forests, grasslands, and even urban areas. They thrive in moist, shaded, and organic-rich soils. |

| Seasonality | Most wild mushrooms grow in specific seasons, typically spring, summer, and fall, depending on the species and climate. |

| Substrate | They grow on various substrates such as decaying wood (saprotrophic), living trees (parasitic), or in symbiotic relationships with plants (mycorrhizal). |

| Spores | Mushrooms reproduce via spores, which are dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing them to colonize new areas. |

| Growth Rate | Growth speed varies by species; some mushrooms can emerge overnight, while others take days or weeks to fully develop. |

| Edibility | Not all wild mushrooms are edible; many are toxic or poisonous. Proper identification is crucial before consumption. |

| Common Species | Examples include chanterelles, morels, porcini, and amanitas, each with unique growth habits and habitats. |

| Ecological Role | Wild mushrooms play a vital role in ecosystems by decomposing organic matter, cycling nutrients, and supporting plant growth. |

| Human Impact | Overharvesting, habitat destruction, and pollution can negatively affect wild mushroom populations. |

| Identification | Accurate identification requires examining features like cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. |

Explore related products

$13.29 $18.95

What You'll Learn

- Optimal Growing Conditions: Wild mushrooms thrive in moist, shaded environments with organic matter like wood or soil

- Types of Mushrooms: Different species grow in specific habitats, such as forests, grasslands, or decaying trees

- Seasonal Growth Patterns: Most wild mushrooms grow in spring, fall, or after rain, depending on the species

- Symbiotic Relationships: Many mushrooms form mycorrhizal partnerships with trees, aiding nutrient exchange for both organisms

- Harvesting Safely: Proper identification is crucial to avoid toxic species when foraging wild mushrooms

Optimal Growing Conditions: Wild mushrooms thrive in moist, shaded environments with organic matter like wood or soil

Wild mushrooms are fascinating organisms that flourish under specific environmental conditions. To understand where and how they grow, it’s essential to focus on their optimal growing conditions. Wild mushrooms thrive in moist, shaded environments where humidity levels are consistently high. This moisture is crucial because mushrooms lack the vascular systems of plants and rely on water to transport nutrients and support their structure. Without adequate moisture, their growth is stunted, and they may even dry out and die. Therefore, areas with regular rainfall, high humidity, or proximity to water sources like streams or wetlands are ideal for their development.

Shade is another critical factor in the growth of wild mushrooms. They typically grow in shaded areas where direct sunlight is minimal. Excessive sunlight can dry out the soil and organic matter, making it inhospitable for mushroom mycelium—the network of thread-like structures that form the foundation of mushrooms. Forests, especially those with dense canopies, provide the perfect shaded environment. Similarly, areas under trees, logs, or other natural shelters are common spots to find wild mushrooms. This shade not only retains moisture but also protects the mushrooms from harsh weather conditions.

Organic matter is the lifeblood of wild mushrooms, as they are saprotrophic organisms that decompose dead or decaying material. They thrive in environments rich in wood, leaves, soil, or other plant debris. Hardwood forests, for instance, are prime locations because fallen trees, branches, and leaves provide ample nutrients for mushroom growth. The mycelium breaks down this organic matter, releasing nutrients that fuel the development of fruiting bodies—the visible part of the mushroom we often see. Without sufficient organic material, mushrooms struggle to grow, as they lack the energy sources needed for their life cycle.

Soil composition also plays a significant role in mushroom growth. Wild mushrooms prefer well-draining, nutrient-rich soil that retains moisture without becoming waterlogged. Loamy or sandy soils with a high organic content are particularly favorable. The pH level of the soil matters too; most mushrooms grow best in slightly acidic to neutral soil. Additionally, the presence of beneficial bacteria and microorganisms in the soil can enhance mushroom growth by aiding in the decomposition process and nutrient cycling.

Finally, temperature is a key factor in determining where wild mushrooms grow. Most species thrive in cool to moderate temperatures, typically ranging from 50°F to 70°F (10°C to 21°C). Extreme heat or cold can inhibit their growth or even kill the mycelium. Seasonal changes often dictate when mushrooms appear, with many species fruiting in spring or fall when temperatures are mild and moisture is abundant. By understanding these optimal growing conditions—moisture, shade, organic matter, soil quality, and temperature—one can better appreciate why wild mushrooms appear in certain environments and how to cultivate them successfully.

Puffball Mushrooms in Utah: Where and When to Find Them

You may want to see also

Types of Mushrooms: Different species grow in specific habitats, such as forests, grasslands, or decaying trees

Wild mushrooms are incredibly diverse, and their growth is closely tied to specific habitats. Different species have adapted to thrive in environments such as forests, grasslands, or decaying trees, each offering unique conditions that support their development. Understanding these habitats is key to identifying and appreciating the variety of mushrooms that grow in the wild. For instance, forests, particularly those with abundant deciduous or coniferous trees, provide the shade, moisture, and organic matter that many mushroom species require. Grasslands, on the other hand, support mushrooms that prefer open, sunny environments with less competition for nutrients. Decaying trees and woody debris are prime habitats for saprotrophic mushrooms, which break down dead organic material as part of their life cycle.

In forested areas, species like the iconic *Amanita muscaria* (fly agaric) and *Boletus edulis* (porcini) are commonly found. These mushrooms often form symbiotic relationships with trees, exchanging nutrients with their roots in a process called mycorrhiza. Forests with oak, beech, or pine trees are particularly rich in mushroom diversity due to the complex ecosystems they support. The shaded, humid conditions under the forest canopy create an ideal environment for mushrooms to fruit, especially during the wetter seasons. Additionally, the leaf litter and fallen branches provide a nutrient-rich substrate for decomposition-loving species.

Grasslands host a different set of mushroom species, such as *Agaricus campestris* (meadow mushroom) and *Marasmius oreades* (fairy ring mushroom). These mushrooms are adapted to environments with more sunlight and less shade, often appearing after rainfall in open fields. Fairy ring mushrooms, for example, grow in circular patterns where the mycelium has depleted nutrients in the center, forcing new growth outward. Grasslands also support mushrooms that have a preference for calcareous soils, which are rich in calcium carbonate and provide a distinct niche for certain species.

Decaying trees and woody debris are critical habitats for mushrooms like *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom) and *Trametes versicolor* (turkey tail). These saprotrophic species play a vital role in nutrient cycling by breaking down lignin and cellulose in dead wood. Oyster mushrooms, for instance, often grow in clusters on fallen logs or standing dead trees, while turkey tail forms bracket-like structures on decaying wood. These habitats are particularly important in forests, where the natural process of tree death and decomposition supports a wide array of fungal life.

Wetlands and riparian zones also support unique mushroom species, such as *Coprinus comatus* (shaggy mane) and *Stropharia rugosoannulata* (wine cap stropharia). These areas provide the high moisture levels that these mushrooms require to thrive. Shaggy manes, for example, are often found in marshy areas or along riverbanks, where their tall, cylindrical caps can be easily spotted. Wine cap stropharia, on the other hand, is cultivated in garden beds but also grows wild in damp, compost-rich environments, highlighting the adaptability of certain species to both natural and managed habitats.

Understanding the specific habitats where different mushroom species grow not only aids in identification but also emphasizes the importance of preserving diverse ecosystems. Each habitat—whether forest, grassland, decaying wood, or wetland—supports a unique fungal community that contributes to the health and balance of the environment. By recognizing these relationships, enthusiasts and researchers can better appreciate the role of wild mushrooms in their respective ecosystems and the conditions that allow them to flourish.

Discovering the Best Trees for Oyster Mushrooms to Thrive On

You may want to see also

Seasonal Growth Patterns: Most wild mushrooms grow in spring, fall, or after rain, depending on the species

Wild mushrooms exhibit distinct seasonal growth patterns that are closely tied to environmental conditions, primarily temperature, humidity, and rainfall. Spring is a prime season for many mushroom species, as the warming soil and increased moisture from melting snow or spring rains create ideal conditions for fungal growth. Species like morels (*Morchella* spp.) are iconic spring mushrooms, often emerging in deciduous forests after the last frost. During this time, the combination of cooler temperatures and ample moisture supports the development of mycelium, the underground network of fungal threads, which eventually produces fruiting bodies—the mushrooms we see above ground.

Fall is another critical season for wild mushroom growth, particularly for species that thrive in cooler temperatures and leaf litter. As deciduous trees shed their leaves, the decomposing organic matter provides nutrients for fungi like chanterelles (*Cantharellus* spp.) and porcini (*Boletus* spp.). The milder temperatures and increased rainfall of autumn create a favorable environment for these mushrooms to flourish. Additionally, the reduced competition from other plants allows fungi to dominate the forest floor, making fall a popular season for mushroom foraging.

While spring and fall are the most common seasons for mushroom growth, rain plays a pivotal role in triggering fruiting across all seasons. Many mushroom species remain dormant until significant rainfall occurs, which replenishes soil moisture and signals the mycelium to produce mushrooms. This is why mushrooms often appear in abundance after heavy rains, even in summer or winter, depending on the species and local climate. For example, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus* spp.) are known to fruit after summer storms, while certain winter mushrooms, like velvet foot (*Flammulina velutipes*), emerge after rain in colder months.

It’s important to note that these seasonal patterns vary by species and geographic location. Tropical regions, for instance, may support year-round mushroom growth due to consistent warmth and humidity, while temperate areas have more defined seasonal cycles. Understanding these patterns is crucial for foragers, as it helps predict when and where specific mushrooms will appear. For example, knowing that lion’s mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) prefers cooler fall temperatures can guide foragers to look for it in late autumn, while spring is the time to search for morels in deciduous woods.

Lastly, environmental factors beyond seasons and rain can influence mushroom growth. Soil type, pH, and the presence of specific trees or plants (mycorrhizal relationships) also play significant roles. For instance, truffles (*Tuber* spp.) grow in symbiotic association with certain trees and are typically harvested in winter. By observing these seasonal and environmental cues, enthusiasts can better understand and predict the growth patterns of wild mushrooms, enhancing both foraging success and appreciation for the intricate world of fungi.

Do Mushrooms Thrive Under Trees? Exploring the Forest Floor Ecosystem

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Symbiotic Relationships: Many mushrooms form mycorrhizal partnerships with trees, aiding nutrient exchange for both organisms

In the intricate web of forest ecosystems, symbiotic relationships play a crucial role in sustaining life. One of the most fascinating examples is the mycorrhizal partnership between mushrooms and trees. This relationship is a prime illustration of how wild mushrooms grow and thrive in their natural habitats. Mycorrhizal associations are formed when fungal hyphae (thread-like structures of mushrooms) colonize the roots of trees, creating a network that facilitates nutrient exchange. This mutualistic bond is essential for the growth and survival of both organisms, highlighting the interconnectedness of forest life.

The process begins when mushroom spores germinate in the soil near tree roots. As the fungal hyphae grow, they intertwine with the tree's root system, forming a mycorrhizal network. This network acts as an extension of the tree's roots, significantly increasing its absorptive surface area. Trees, being stationary organisms, often struggle to access nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen that are present in hard-to-reach areas of the soil. Mushrooms, with their extensive hyphal networks, efficiently extract these nutrients and transport them to the tree. In return, the tree provides the mushroom with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis, which are essential for fungal growth.

This nutrient exchange is particularly vital in nutrient-poor soils, where trees might otherwise struggle to survive. For instance, in boreal forests, mycorrhizal fungi help coniferous trees like pines and spruces access essential nutrients, ensuring their growth and resilience. Similarly, in temperate forests, deciduous trees benefit from these partnerships, especially during their early growth stages. The mushrooms, in turn, rely on the trees for energy-rich compounds, which they cannot produce on their own. This interdependence underscores the significance of mycorrhizal relationships in the growth and proliferation of wild mushrooms.

The mycorrhizal network also plays a critical role in forest communication and resilience. Known as the "Wood Wide Web," this underground network allows trees to share resources and signals, enhancing their collective ability to withstand stressors like drought or disease. For example, if one tree is under attack by insects, it can send chemical signals through the fungal network to warn neighboring trees, which can then activate their defenses. Mushrooms, as integral components of this network, contribute to the overall health and stability of forest ecosystems, further emphasizing their role in the growth and survival of wild mushrooms.

Understanding these symbiotic relationships not only sheds light on how wild mushrooms grow but also highlights their ecological importance. By forming mycorrhizal partnerships with trees, mushrooms ensure their own survival while supporting the growth and health of forest vegetation. This mutualistic bond is a testament to the intricate balance of nature, where cooperation between different organisms leads to thriving ecosystems. For anyone interested in the growth of wild mushrooms, recognizing the significance of these relationships provides valuable insights into the conditions and interactions that foster their development in natural settings.

Wisconsin's Morel Mushroom Hunt: Where and When to Find Them

You may want to see also

Harvesting Safely: Proper identification is crucial to avoid toxic species when foraging wild mushrooms

Wild mushrooms grow abundantly in various environments, from forests and meadows to decaying wood and soil. While many species are edible and prized for their unique flavors, others can be toxic or even deadly. This makes proper identification an essential skill for anyone interested in foraging. Harvesting wild mushrooms without accurate knowledge can lead to serious health risks, including poisoning or long-term illness. Therefore, understanding the characteristics of both edible and toxic species is the first step in safe foraging.

Proper identification begins with thorough research and education. Foragers should invest time in studying field guides, attending workshops, or joining mycological societies to learn about the mushrooms in their region. Key features to observe include the mushroom’s cap shape, color, and texture; the presence or absence of gills, pores, or spines; the color and structure of the stem; and any distinctive odors or tastes. Some toxic species closely resemble edible ones, so small details can make a significant difference. For example, the deadly Amanita species often mimic the appearance of edible Agaricus mushrooms, but their distinct volva (cup-like structure at the base) and ring on the stem are warning signs.

When foraging, it’s crucial to examine each mushroom carefully and avoid making assumptions based on partial information. Always carry a reliable field guide or use a trusted identification app, but remember that technology is not infallible. If in doubt, leave the mushroom undisturbed. Additionally, consider collecting samples for further study at home, but never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Cross-referencing with multiple sources and consulting experienced foragers can provide added confidence.

Harvesting techniques also play a role in safety and sustainability. Use a knife to cut mushrooms at the base of the stem, leaving the mycelium (root-like structure) intact to allow future growth. Avoid over-harvesting from a single area to preserve the ecosystem. Always forage in clean, unpolluted environments, as mushrooms can absorb toxins from their surroundings, making even edible species unsafe to eat.

Finally, if you’re new to foraging, consider going with an experienced guide or mentor. They can provide hands-on training and help you develop the skills needed to identify mushrooms accurately. Remember, the goal is not just to harvest mushrooms but to do so responsibly and safely. By prioritizing proper identification and adopting ethical foraging practices, you can enjoy the rewards of wild mushrooms while minimizing risks to yourself and the environment.

Do Morel Mushrooms Thrive Near Walnut Trees? Exploring the Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wild mushrooms can grow in a variety of environments, including forests, grasslands, and even urban areas, but they require specific conditions like moisture, organic matter, and suitable temperatures to thrive.

Wild mushrooms often grow in late summer, fall, and early winter, though some species may appear in spring, depending on climate and environmental conditions.

Yes, many wild mushrooms grow after rain because they require moisture to fruit. Rain provides the necessary hydration for mushroom mycelium to develop into visible mushrooms.

Yes, wild mushrooms can grow in backyards if there is sufficient organic material (like wood chips or decaying leaves), moisture, and shade. However, not all backyard mushrooms are safe to eat.

Yes, many wild mushrooms grow on trees as they are either decomposers of dead wood or have symbiotic relationships with living trees. These are often referred to as wood-decaying or mycorrhizal mushrooms.