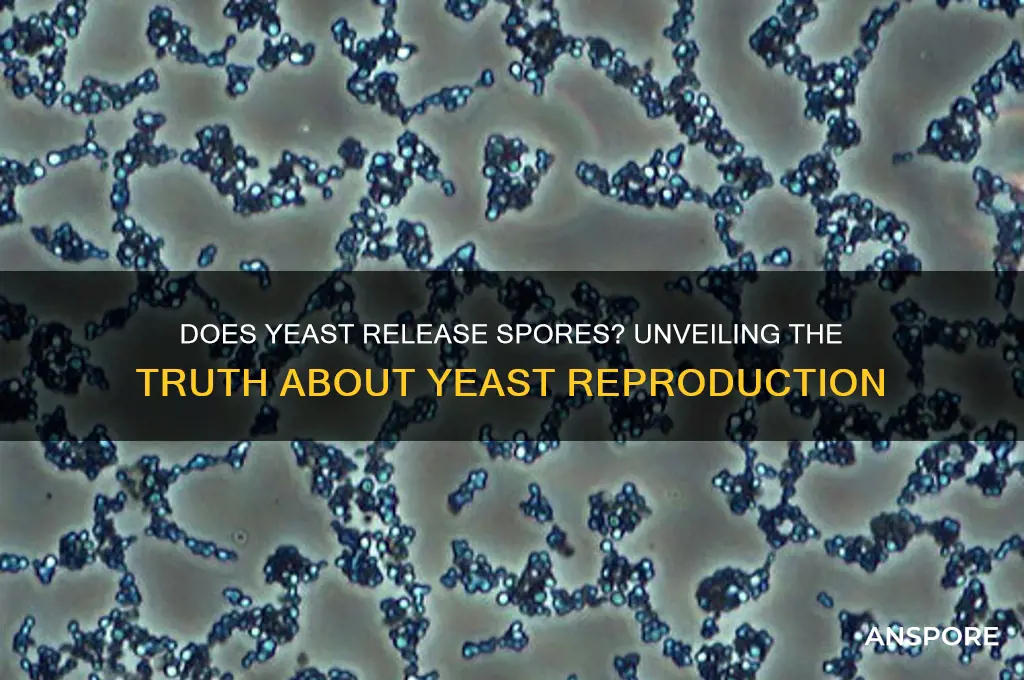

Yeast, a single-celled microorganism belonging to the fungus kingdom, is widely recognized for its role in fermentation processes, such as baking and brewing. While many fungi reproduce by releasing spores, yeast primarily reproduces asexually through a process called budding, where a small outgrowth forms on the parent cell and eventually detaches to become a new cell. However, certain yeast species, particularly those in the genus *Ascomycota*, can also produce spores under specific environmental conditions, such as nutrient depletion or stress. These spores, known as ascospores, are formed within a sac-like structure called an ascus and serve as a means of survival and dispersal. Understanding whether and how yeast releases spores is crucial for fields like microbiology, biotechnology, and food science, as it impacts yeast's adaptability, longevity, and applications in various industries.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Yeast Release Spores? | Yes, certain types of yeast (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) can form spores under specific conditions. |

| Type of Spores | Ascospores (produced in asci during sexual reproduction). |

| Conditions for Sporulation | Nutrient deprivation, particularly nitrogen depletion, triggers sporulation. |

| Purpose of Spores | Survival in harsh environments, long-term persistence, and genetic recombination. |

| Structure of Spores | Thick-walled, highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals. |

| Germination | Spores can germinate under favorable conditions to resume vegetative growth. |

| Relevance | Important in biotechnology, food production (e.g., brewing, baking), and genetic studies. |

| Non-Sporulating Yeasts | Some yeast species (e.g., Candida albicans) do not form spores and reproduce primarily by budding. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Yeast Life Cycle Stages: Yeast reproduces asexually by budding, but some species form spores under stress

- Sporulation Process: Sporulation occurs when yeast cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores

- Types of Yeast Spores: Ascospores are common in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, formed in asci structures

- Environmental Triggers: Nutrient depletion, temperature changes, or pH shifts can induce spore formation

- Survival Function: Spores act as dormant, resilient forms, aiding yeast survival in harsh conditions

Yeast Life Cycle Stages: Yeast reproduces asexually by budding, but some species form spores under stress

Yeast, a single-celled fungus, primarily reproduces asexually through a process called budding, where a small daughter cell forms on the parent cell and eventually detaches. This method is efficient under favorable conditions, allowing yeast populations to grow rapidly. However, when faced with environmental stressors such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or high ethanol concentrations, certain yeast species, like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, adopt a survival strategy by forming spores. These spores are highly resilient, capable of enduring harsh conditions for extended periods until the environment becomes conducive to growth again.

The formation of spores in yeast is a complex, energy-intensive process triggered by stress. Unlike budding, which is a quick and continuous method of reproduction, sporulation is a last-resort mechanism. During sporulation, a diploid yeast cell undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid spores, each encased in a protective wall. This wall is composed of layers rich in chitin and other compounds, making the spores resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals. For example, in brewing or winemaking, yeast spores can survive the high alcohol content that would kill vegetative cells, ensuring the yeast’s long-term survival.

Understanding the sporulation process has practical implications, particularly in industries like baking, brewing, and biotechnology. For instance, bakers often use active dry yeast, which contains dormant spores that activate when rehydrated. Similarly, in brewing, sporulation can affect beer quality, as spores may survive fermentation and impact flavor profiles. To control sporulation, brewers and winemakers monitor factors like nutrient availability and temperature, ensuring yeast remains in its vegetative, budding state. In biotechnology, yeast spores are studied for their potential in preserving genetically modified strains or creating robust cell factories.

While sporulation is a survival mechanism, it’s not without drawbacks. The process diverts energy from growth and metabolism, reducing yeast’s immediate productivity. For homebrewers or bakers, this means that stressed yeast may produce less carbon dioxide or alcohol, affecting dough rise or fermentation efficiency. To prevent unwanted sporulation, maintain optimal conditions: keep temperatures between 25–30°C (77–86°F), ensure adequate nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and vitamins), and avoid extreme pH levels. Regularly monitoring these parameters can help keep yeast in its budding phase, maximizing its utility in various applications.

In summary, while budding is yeast’s default reproductive strategy, sporulation is a specialized response to stress, offering long-term survival at the cost of immediate productivity. Recognizing the conditions that trigger sporulation and managing them effectively can enhance outcomes in both industrial and home settings. Whether you’re fermenting beer, baking bread, or conducting research, understanding yeast’s dual reproductive strategies ensures you harness its full potential while avoiding pitfalls.

Are Pine Cones Spores? Unraveling Nature's Seed Dispersal Mysteries

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process: Sporulation occurs when yeast cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores

Yeast, a single-celled fungus, has a remarkable ability to adapt to environmental stresses through sporulation. This process is not merely a survival mechanism but a complex biological transformation. When nutrients become scarce or conditions turn unfavorable, certain yeast species, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, initiate sporulation. This involves a switch from the typical vegetative growth phase to a reproductive phase where cells undergo meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid spores. These spores are highly resilient, capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, desiccation, and other harsh conditions, ensuring the yeast’s long-term survival.

The sporulation process begins with the formation of a diploid cell, which then undergoes meiosis I and II to produce four haploid nuclei. These nuclei are packaged into spores within the original cell wall, forming an ascus. Each ascus typically contains four spores, though variations can occur. The key to successful sporulation lies in the precise regulation of gene expression, with over 800 genes activated or repressed during this process. For instance, the *IME1* gene acts as a master regulator, triggering the onset of meiosis when induced by starvation signals. Understanding this genetic choreography is crucial for both scientific research and industrial applications, such as improving yeast strains for fermentation or biotechnology.

From a practical standpoint, inducing sporulation in yeast requires specific conditions. Laboratory protocols often involve transferring yeast cells to a sporulation medium, typically consisting of 1% potassium acetate and 0.1% yeast extract, adjusted to pH 7.0. This nutrient-poor environment mimics starvation, prompting the cells to initiate sporulation. The process takes approximately 5–7 days at 25°C, with spore maturation monitored using microscopy or staining techniques like DAPI to visualize nuclear division. For homebrewers or hobbyists, achieving sporulation may not be a goal, but understanding this process can explain why yeast cultures sometimes form resilient spores when left unattended in suboptimal conditions.

Comparatively, yeast sporulation shares similarities with bacterial endospore formation, though the mechanisms and outcomes differ. While bacterial endospores are metabolically dormant, yeast spores remain viable and can quickly revert to vegetative growth when conditions improve. This distinction highlights the unique evolutionary strategy of yeast, balancing dormancy with readiness for rapid proliferation. In industries like baking and brewing, where yeast vitality is critical, preventing unintended sporulation is essential, as spores may affect fermentation efficiency or product consistency.

In conclusion, the sporulation process in yeast is a fascinating example of cellular adaptability, driven by environmental cues and tightly regulated genetics. Whether studied in a lab or observed in natural settings, this mechanism underscores yeast’s role as a model organism for understanding eukaryotic biology. For practitioners, recognizing the conditions that trigger sporulation can help optimize yeast cultures or troubleshoot issues in fermentation processes. By appreciating the intricacies of sporulation, we gain deeper insights into the resilience and versatility of this microscopic powerhouse.

Are Spore Servers Down? Troubleshooting Tips and Current Status Updates

You may want to see also

Types of Yeast Spores: Ascospores are common in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, formed in asci structures

Yeast, a microscopic fungus, is not a monolithic entity but a diverse group with varied reproductive strategies. Among these, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly known as baker’s or brewer’s yeast, stands out for its ability to form ascospores, a specialized type of spore encased within a sac-like structure called an ascus. This reproductive mechanism is a survival tactic, allowing the yeast to endure harsh conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation. Understanding ascospores is crucial for industries like baking, brewing, and biotechnology, where yeast health and resilience directly impact product quality.

Ascospores are formed through a process called ascosporegenesis, which occurs during the sexual reproduction of *S. cerevisiae*. Unlike asexual reproduction, which produces clones, sexual reproduction involves the fusion of two haploid cells (of opposite mating types, a and α) to form a diploid cell. This diploid cell then undergoes meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in four haploid nuclei. These nuclei are packaged into asci, each containing eight ascospores. The asci provide a protective environment, ensuring the spores’ viability until conditions improve. For example, in brewing, ascospores can remain dormant in spent grains or equipment, only to germinate when reintroduced to a favorable medium.

The formation of ascospores is not just a biological curiosity but a practical consideration for yeast cultivation. To induce ascospore formation, yeast cultures are typically subjected to nutrient-limited conditions, such as nitrogen starvation. This stress triggers the yeast to enter its sexual cycle. For laboratory or industrial settings, a common protocol involves mixing equal amounts of a and α cells in a sporulation medium (e.g., 1% potassium acetate, 0.1% yeast extract) and incubating at 25°C for 5–7 days. The success of this process can be assessed by microscopic examination, where mature asci appear as elongated sacs containing refractile spores.

Comparatively, ascospores differ from other yeast spores, such as basidiospores found in basidiomycete fungi or conidia produced asexually by some yeasts. Ascospores are thicker-walled and more resilient, capable of surviving for years in adverse conditions. This durability makes them valuable in biotechnology, where yeast strains are often stored as ascospore suspensions for long-term preservation. However, their formation requires specific genetic and environmental conditions, limiting their occurrence to certain yeast species like *S. cerevisiae*.

In practical applications, ascospores are harnessed for genetic studies and strain improvement. Since meiosis shuffles genetic material, ascospores exhibit genetic diversity, making them ideal for mapping traits or creating hybrid strains. For instance, in wine production, ascospores from wild *S. cerevisiae* strains can introduce desirable traits like enhanced fermentation efficiency or flavor profiles. However, their formation can also be a nuisance in industrial settings, as dormant ascospores may contaminate equipment or outcompete desired strains. Thus, while ascospores are a testament to yeast’s adaptability, their management requires careful consideration of both benefits and challenges.

Are Bacterial Spores Resistant to Antibiotics? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Nutrient depletion, temperature changes, or pH shifts can induce spore formation

Yeast, a eukaryotic microorganism, is known for its role in fermentation and baking, but its survival strategies are equally fascinating. Under favorable conditions, yeast thrives through asexual reproduction, budding to form new cells. However, when the environment becomes hostile, certain yeast species, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* and *Schizosaccharomyces pombe*, can undergo sporulation—a process where haploid cells transform into spores. These spores are highly resilient, capable of withstanding extreme conditions like desiccation, heat, and chemicals. Understanding what triggers spore formation is crucial for both scientific research and industrial applications.

Nutrient depletion is a primary environmental trigger for spore formation in yeast. When essential nutrients like nitrogen, carbon, or sulfur become scarce, yeast cells sense starvation and initiate the sporulation pathway. For instance, in laboratory settings, researchers often induce sporulation by transferring yeast cells to a nutrient-poor medium, such as potassium acetate (2% w/v) at pH 7.0. This shift mimics natural conditions where resources are limited, prompting yeast to enter a dormant state. In brewing or winemaking, nutrient depletion at the end of fermentation can also trigger sporulation, though this is less common due to the presence of residual sugars. To control sporulation in industrial processes, monitoring nutrient levels and adjusting media composition is essential.

Temperature changes play a pivotal role in sporulation, particularly in species like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. While yeast typically grows optimally at 25–30°C (77–86°F), a shift to lower temperatures, around 15–20°C (59–68°F), can enhance sporulation efficiency. This temperature drop simulates environmental stress, signaling to the yeast that conditions are deteriorating. For example, in natural settings, seasonal temperature fluctuations can induce sporulation in wild yeast populations. In laboratory or industrial settings, maintaining a controlled temperature gradient can optimize spore yield. However, extreme temperatures above 37°C (98.6°F) can inhibit sporulation and even kill yeast cells, so precision is key.

PH shifts are another critical environmental trigger for spore formation. Yeast thrives in slightly acidic to neutral environments, typically at pH 4.0–7.0. Deviations from this range, particularly toward alkalinity (pH > 7.5), can stress yeast cells and induce sporulation. For example, in dairy fermentation, pH changes due to lactic acid production can trigger sporulation in contaminating yeast strains. To experimentally induce sporulation, researchers often adjust the pH of the medium to 7.5–8.0 using buffers like potassium phosphate. In practical applications, such as food preservation, controlling pH can prevent unwanted sporulation or encourage it for specific purposes, like producing yeast spores for probiotics.

Understanding these environmental triggers allows scientists and industries to manipulate yeast behavior effectively. For instance, in biotechnology, inducing sporulation can produce robust yeast spores for use in probiotics or enzyme production. Conversely, in brewing or baking, preventing sporulation ensures consistent fermentation and product quality. By controlling nutrient levels, temperature, and pH, one can either promote or inhibit spore formation, depending on the desired outcome. This knowledge bridges the gap between fundamental biology and applied science, offering practical solutions for diverse fields.

Detecting Mold Spores in Air: Effective Testing Methods Explained

You may want to see also

Survival Function: Spores act as dormant, resilient forms, aiding yeast survival in harsh conditions

Yeast, a microscopic fungus, employs a remarkable survival strategy through the production of spores. These spores are not merely reproductive units but serve as a dormant, resilient form that enables yeast to endure harsh environmental conditions. When nutrients become scarce or temperatures rise beyond optimal levels, certain yeast species, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, undergo sporulation. This process transforms the yeast cell into a highly resistant spore capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, desiccation, and even radiation. For instance, yeast spores can survive for years in a dry state, only to revive and resume growth when conditions improve.

The sporulation process is a complex, energy-intensive transformation that involves the formation of four haploid spores within a protective outer shell called the ascus. This structure acts as a barrier against external stressors, ensuring the genetic material remains intact. In brewing and baking industries, this resilience is both a blessing and a challenge. While spores can contaminate equipment and survive cleaning processes, their ability to remain dormant until conditions are favorable highlights their evolutionary brilliance. Understanding this mechanism allows industries to develop more effective sterilization methods, such as using high-pressure steam (121°C for 15–30 minutes) to eliminate spores.

From a practical standpoint, homebrewers and bakers can leverage this knowledge to control yeast behavior. For example, storing yeast at temperatures below 4°C can slow metabolic activity but may not eliminate spores. Instead, freezing yeast at -20°C or using commercial yeast strains specifically cultured for sporulation resistance can ensure consistency in fermentation processes. Additionally, maintaining a clean, dry environment reduces the likelihood of spore activation, as moisture is a key trigger for germination.

Comparatively, bacterial spores, such as those from *Bacillus* species, share similarities in resilience but differ in structure and germination requirements. Yeast spores, however, are unique in their ability to retain metabolic flexibility upon revival, quickly adapting to new environments. This adaptability makes yeast spores a subject of interest in biotechnology, where their resilience is harnessed for applications like biofuel production and environmental remediation.

In conclusion, the survival function of yeast spores is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. By acting as dormant, resilient forms, these spores ensure yeast’s persistence in adverse conditions, offering both challenges and opportunities across industries. Whether managing contamination or optimizing fermentation, understanding this mechanism empowers individuals to work with yeast more effectively, turning a microscopic survival strategy into a macroscopic advantage.

Are Psilocybe Cubensis Spores Legal in California? A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, certain types of yeast, particularly those in the genus *Ascomycota*, release spores as part of their reproductive cycle. These spores are called ascospores and are produced within a sac-like structure called an ascus.

Yeast releases spores as a survival and dispersal mechanism. Spores are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions, such as heat, cold, and desiccation, allowing yeast to survive in unfavorable environments and disperse to new habitats when conditions improve.

No, not all yeast species release spores. For example, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, commonly used in baking and brewing, reproduces primarily through budding and does not form spores. Only specific yeast species, like those in the *Ascomycota* group, produce spores as part of their life cycle.