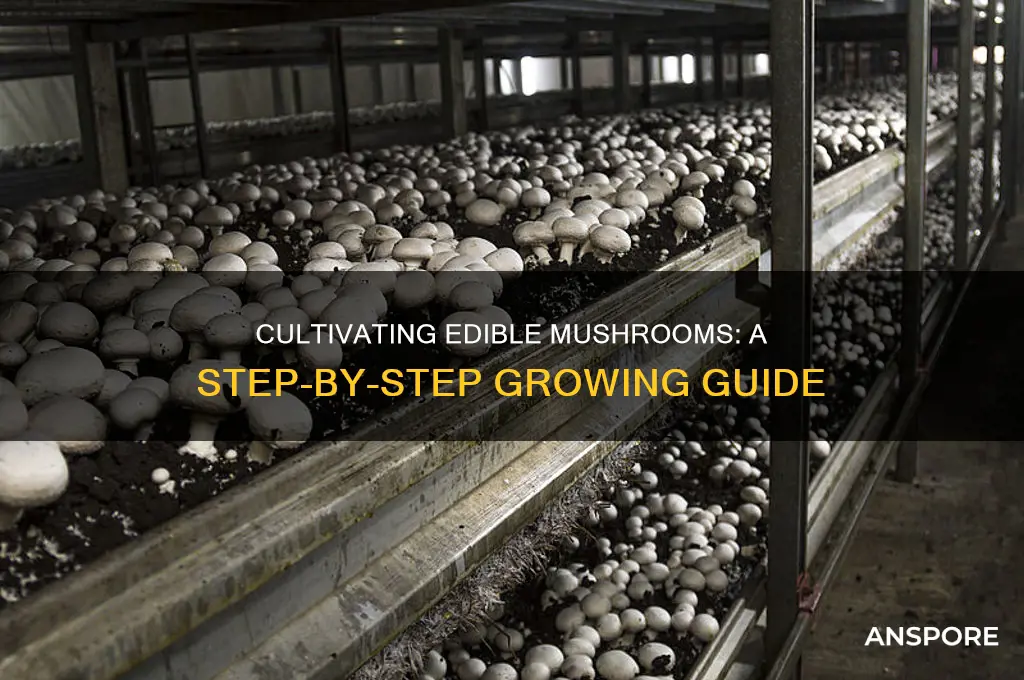

Edible mushrooms are cultivated through a precise and controlled process that mimics their natural growing conditions. Typically, cultivation begins with sterilized substrate materials, such as straw, sawdust, or compost, which are enriched with nutrients to support fungal growth. Mushroom spores or mycelium (the vegetative part of the fungus) are then introduced to the substrate, often in a sterile environment to prevent contamination. The substrate is placed in a dark, humid, and temperature-controlled space, encouraging the mycelium to colonize the material. Once fully colonized, the growing environment is adjusted to trigger fruiting, often by introducing light, fresh air, and specific humidity levels. Over several weeks, mushrooms emerge, grow, and are harvested at peak maturity, ensuring optimal flavor, texture, and nutritional value. This method allows for year-round production and a consistent supply of edible mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Substrate | Mushrooms are grown on organic substrates like straw, sawdust, wood chips, or compost, which provide nutrients. |

| Spawn | Mycelium (mushroom "seeds") is introduced into the substrate to initiate growth. |

| Environment | Controlled conditions: temperature (55–75°F / 13–24°C), humidity (85–95%), and darkness or low light. |

| Humidity | High humidity is maintained to prevent drying and encourage fruiting. |

| Ventilation | Proper airflow is essential to prevent CO₂ buildup and ensure healthy growth. |

| Light | Minimal light is needed; indirect or artificial light suffices for fruiting. |

| pH Level | Substrate pH is maintained between 5.5 and 6.5 for optimal growth. |

| Fruiting | Mushrooms form fruiting bodies (caps and stems) after the mycelium colonizes the substrate. |

| Harvesting | Mushrooms are harvested when caps are fully open but before spores drop. |

| Common Varieties | Button, shiitake, oyster, portobello, and lion's mane mushrooms. |

| Growing Methods | Indoor (bags, trays, or shelves), outdoor (logs or beds), or commercial farms. |

| Time to Harvest | 2–4 weeks after spawning, depending on the species and conditions. |

| Pest Control | Natural methods like beneficial insects or organic fungicides are used. |

| Sustainability | Mushrooms are eco-friendly, using agricultural waste as substrate. |

| Nutritional Value | Rich in protein, vitamins (B, D), minerals, and antioxidants. |

| Storage | Fresh mushrooms are stored in cool, dry conditions or refrigerated. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Substrate Preparation: Sterilize or pasteurize growing medium (straw, sawdust, grains) to eliminate contaminants

- Spawn Inoculation: Mix mushroom spawn evenly into the prepared substrate for mycelium growth

- Incubation Phase: Maintain optimal temperature, humidity, and darkness for mycelium colonization

- Fruiting Conditions: Adjust light, humidity, and ventilation to trigger mushroom formation

- Harvesting Techniques: Pick mature mushrooms carefully to avoid damaging mycelium or remaining pins

Substrate Preparation: Sterilize or pasteurize growing medium (straw, sawdust, grains) to eliminate contaminants

The foundation of successful mushroom cultivation lies in the substrate—the material on which mushrooms grow. Whether you're using straw, sawdust, or grains, the medium must be free of contaminants to prevent competing organisms from hijacking your crop. This is where sterilization or pasteurization comes in, acting as the first line of defense in your mushroom-growing endeavor.

Analytical Perspective:

Contaminants like bacteria, molds, and other fungi thrive in the same organic environments that mushrooms favor. Without proper treatment, these competitors can outpace your mushroom mycelium, leading to crop failure. Sterilization, typically achieved through high-pressure steam (autoclaving) at 121°C (250°F) for 1–2 hours, ensures complete elimination of all microorganisms. Pasteurization, a milder process involving temperatures of 60–80°C (140–176°F) for 1–2 hours, reduces but does not eradicate all contaminants. The choice between the two depends on your substrate and resources: grains often require sterilization, while straw can often succeed with pasteurization.

Instructive Steps:

To pasteurize straw, soak it in water heated to 70°C (158°F) for 1–2 hours, then drain and cool. For sawdust, mix it with water to achieve a moisture content of 60–70%, then heat it in a large pot or steam chamber to 75°C (167°F) for 1 hour. Grains, however, demand sterilization due to their higher risk of contamination. Use an autoclave or a pressure cooker, ensuring the core temperature reaches 121°C (250°F) for at least 1 hour. Always allow the substrate to cool to around 25°C (77°F) before inoculating with spawn to avoid damaging the mycelium.

Comparative Insight:

While sterilization guarantees a contaminant-free substrate, it requires specialized equipment like an autoclave, making it less accessible for small-scale growers. Pasteurization, on the other hand, can be done with basic tools—a large pot, thermometer, and heat source—but carries a higher risk of contamination. For hobbyists, pasteurization is often the practical choice, while commercial growers may opt for sterilization to ensure consistency and yield.

Practical Tips:

When working with straw, ensure it’s chopped into 5–10 cm (2–4 inch) lengths for even treatment. For sawdust, use a moisture meter to verify hydration levels before pasteurization. Always wear gloves and protective gear when handling hot substrates. If using a pressure cooker for sterilization, avoid overloading it to ensure proper steam penetration. Finally, store treated substrates in a clean, sealed environment until inoculation to prevent recontamination.

Substrate preparation is a critical step in mushroom cultivation, and the choice between sterilization and pasteurization hinges on your resources, scale, and risk tolerance. By mastering these techniques, you create an optimal environment for mushroom growth, setting the stage for a bountiful harvest.

Are All Polypore Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Spawn Inoculation: Mix mushroom spawn evenly into the prepared substrate for mycelium growth

Mushroom cultivation begins with a critical step: introducing the mushroom spawn to the substrate. Spawn inoculation is the process of mixing mushroom mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—evenly into a prepared substrate, which serves as the nutrient base for growth. This step is pivotal because it determines how efficiently the mycelium colonizes the substrate, directly impacting yield and quality. Without proper inoculation, the mycelium may struggle to spread, leading to uneven growth or contamination.

To achieve successful inoculation, start by ensuring both the spawn and substrate are at optimal conditions. The substrate should be fully prepared—sterilized or pasteurized, cooled to around 75–80°F (24–27°C), and moist but not waterlogged. The spawn, typically grain-based, should be fully colonized by the mycelium, appearing white and healthy. Mix the spawn into the substrate at a ratio of 1:10 to 1:20 (spawn to substrate by volume), depending on the mushroom species and substrate type. For example, oyster mushrooms often require less spawn (1:20), while shiitake may need more (1:10). Use clean hands or sanitized tools to blend the spawn thoroughly, ensuring no clumps remain, as these can hinder colonization.

A common mistake in spawn inoculation is uneven distribution, which can create "dead zones" where mycelium fails to grow. To avoid this, break up any spawn clumps before mixing and use a folding technique rather than stirring, which can compact the substrate. After mixing, the substrate should appear uniformly speckled with spawn. Transfer the inoculated substrate into growing containers or bags immediately to minimize exposure to contaminants. Seal or cover the substrate to retain moisture and provide darkness, which encourages mycelium growth.

The success of spawn inoculation also depends on environmental conditions post-mixing. Maintain temperatures between 70–75°F (21–24°C) and humidity levels above 60% for most edible mushroom species. Monitor for signs of contamination, such as green or black mold, which indicates the need to discard the batch. Properly inoculated substrate will show signs of colonization within 7–14 days, with white mycelium spreading throughout. This stage, known as the incubation period, is crucial for establishing a strong foundation for fruiting.

In summary, spawn inoculation is a precise yet accessible step in mushroom cultivation. By focusing on even distribution, proper ratios, and optimal conditions, growers can ensure robust mycelium growth, setting the stage for a successful harvest. Attention to detail during this phase pays dividends in the form of healthy, productive mushroom crops.

Are Conk Mushrooms Edible? Exploring Safety and Culinary Potential

You may want to see also

Incubation Phase: Maintain optimal temperature, humidity, and darkness for mycelium colonization

The incubation phase is a critical period in mushroom cultivation, akin to nurturing a seedling in its earliest, most vulnerable stage. During this time, the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—colonizes the substrate, laying the foundation for future fruiting bodies. To ensure successful colonization, maintaining optimal environmental conditions is paramount. Temperature, humidity, and darkness are the trifecta of factors that dictate the mycelium’s ability to thrive. For most edible mushroom species, such as shiitake, oyster, and lion’s mane, the ideal temperature range falls between 70°F and 75°F (21°C to 24°C). Deviations from this range can slow growth or even halt colonization entirely. A digital thermostat or a simple heating pad can help regulate temperature, especially in cooler environments. Humidity levels must also be carefully managed, typically maintained at 60-70%, to prevent the substrate from drying out while avoiding excessive moisture that could lead to contamination. A hygrometer and a light misting of water can help strike this balance. Darkness is equally crucial during this phase, as light can disrupt the mycelium’s growth patterns. Storing incubation containers in a dark room or covering them with light-blocking material ensures the mycelium remains undisturbed.

Consider the incubation phase as a delicate dance, where precision in environmental control can make or break the harvest. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are particularly sensitive to temperature fluctuations, with colonization slowing significantly below 65°F (18°C). In contrast, button mushrooms (*Agaricus bisporus*) tolerate a slightly cooler range of 65°F to 70°F (18°C to 21°C). Humidity management is equally species-specific; for example, lion’s mane mushrooms (*Hericium erinaceus*) require higher humidity levels, around 75%, during incubation. Practical tips include using a humidifier or placing a tray of water near the incubation area to maintain moisture. Darkness is non-negotiable, as even brief exposure to light can trigger premature fruiting or uneven growth. A closet or a dedicated grow tent lined with black plastic can serve as an ideal incubation space.

One common mistake cultivators make is underestimating the importance of sterilization during this phase. Contaminants like mold or bacteria thrive in the same conditions as mycelium, competing for resources and potentially ruining the batch. To mitigate this, sterilize all equipment and substrates before inoculation, and maintain a clean environment throughout incubation. For example, autoclaving substrates at 121°C (250°F) for 30 minutes ensures they are free from competing organisms. Additionally, using a still air box or laminar flow hood during inoculation minimizes airborne contaminants. Patience is another virtue in this phase; rushing the process by increasing temperature or humidity can lead to weak mycelium or contamination. Allow 2-4 weeks for full colonization, depending on the species and substrate used.

Comparing the incubation phase to other stages of mushroom cultivation highlights its unique demands. While fruiting requires light and fresh air exchange, incubation thrives in darkness and isolation. This contrast underscores the need for a dedicated space or system tailored to each phase. For small-scale growers, repurposing a spare closet or building a simple incubation chamber with a thermostat-controlled heater and humidity monitor can be cost-effective. Larger operations may invest in climate-controlled rooms or incubators designed specifically for mycelium colonization. Regardless of scale, consistency is key; daily monitoring of temperature and humidity ensures the mycelium remains in its optimal growth zone.

In conclusion, the incubation phase is a meticulous yet rewarding step in mushroom cultivation. By maintaining precise temperature, humidity, and darkness, growers create an environment where mycelium can flourish undisturbed. Species-specific requirements, sterilization practices, and patience are essential components of success. Whether cultivating for personal use or commercial production, mastering this phase sets the stage for a bountiful harvest. Treat it as the foundation of your mushroom-growing journey, and the results will speak for themselves.

Are Hedgehog Mushrooms Safe to Eat? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$30.19 $32.99

Fruiting Conditions: Adjust light, humidity, and ventilation to trigger mushroom formation

Mushrooms, unlike plants, don’t rely on sunlight for energy, but light still plays a subtle yet crucial role in their fruiting. Most edible mushrooms, such as shiitake and oyster varieties, require indirect, low-intensity light to signal the transition from mycelial growth to fruiting. Think of it as a gentle nudge rather than a spotlight—12 to 16 hours of dim, cool light (around 200–400 lux) per day is ideal. Avoid direct sunlight, which can dry out the substrate or overheat the environment. LED grow lights with a neutral white spectrum are a practical choice, as they provide the necessary light without generating excess heat. This simple adjustment mimics the forest floor conditions mushrooms evolved under, triggering the formation of primordia—the tiny pins that develop into full-sized mushrooms.

Humidity is the unsung hero of fruiting conditions, acting as the catalyst that transforms mycelium into mushrooms. Fruiting bodies require a relative humidity of 85–95% to develop properly, as they lose moisture rapidly through their gills. Achieve this by misting the growing area 2–3 times daily or using a humidifier. However, high humidity alone isn’t enough; it must be balanced with proper ventilation to prevent mold and stagnant air. A common mistake is over-misting, which can lead to waterlogged substrate or competing molds. Pro tip: Use a hygrometer to monitor levels and ensure consistency, especially during the critical pinning stage when mushrooms are most vulnerable.

Ventilation is often overlooked but is critical for healthy fruiting. While mushrooms thrive in humid environments, stagnant air can suffocate them or promote contaminants. Aim for a gentle, constant airflow—think of it as a soft breeze rather than a gusty wind. Position a small fan on low speed to circulate air without drying out the substrate. Proper ventilation also helps regulate carbon dioxide levels, which should be kept below 1,000 ppm for optimal fruiting. Without adequate airflow, mushrooms may stretch unnaturally, develop weak stems, or fail to form caps. This delicate balance ensures that humidity supports growth without creating a breeding ground for unwanted organisms.

Mastering fruiting conditions is a blend of art and science, requiring attention to detail and patience. Light, humidity, and ventilation aren’t isolated factors but interconnected elements that must be fine-tuned together. For instance, increasing light exposure without proper airflow can cause overheating, while high humidity without ventilation invites mold. Start with a controlled environment—a grow tent or repurposed container—and adjust parameters incrementally. Observe how your mushrooms respond: slow pinning may indicate insufficient light, while shriveled caps suggest low humidity. With practice, you’ll develop an intuition for these conditions, transforming mycelium into a bountiful harvest of edible mushrooms.

Are Snakehead Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Identification and Safety

You may want to see also

Harvesting Techniques: Pick mature mushrooms carefully to avoid damaging mycelium or remaining pins

The delicate dance of mushroom harvesting demands precision and care, especially when dealing with mature specimens. A single misstep can damage the mycelium, the intricate network of fungal threads that sustains future growth, or harm remaining pins—the tiny, nascent mushrooms that hold the promise of the next flush. This section delves into the art of harvesting mature mushrooms with minimal disruption, ensuring the longevity and productivity of your mushroom bed.

The Gentle Twist-and-Pull Method

To harvest without causing harm, employ the twist-and-pull technique. Grasp the mushroom firmly at its base, just above the substrate, and apply a gentle twisting motion while pulling upward. This action severs the mushroom from the mycelium cleanly, reducing the risk of tearing or uprooting surrounding pins. Avoid yanking or tugging forcefully, as this can disturb the substrate and damage the delicate mycelial network. For larger varieties like portobellos or shiitakes, use your free hand to support the cap, preventing breakage.

Timing Matters: Harvest at Peak Maturity

Harvesting at the right moment is crucial. Mushrooms are best picked when their caps are fully open but before the gills begin to drop spores. For button mushrooms, this means harvesting when the cap is still slightly curved inward. For oyster mushrooms, wait until the edges of the cap begin to flatten but haven’t yet turned upward. Overripe mushrooms not only degrade in quality but also risk contaminating the substrate with spores, potentially introducing competing molds or fungi. A well-timed harvest ensures optimal flavor and texture while safeguarding the mycelium.

Tools of the Trade: Keep It Simple and Sanitary

While your hands are often the best tools for harvesting, small, sharp knives or scissors can be useful for stubborn stems or hard-to-reach mushrooms. Sterilize your tools with rubbing alcohol (70% isopropyl) before and after use to prevent the spread of contaminants. Avoid using blunt or dirty instruments, as these can crush stems or introduce pathogens that threaten the mycelium. For commercial growers, a harvesting basket with a flat bottom and shallow sides allows you to collect mushrooms without compressing them, reducing the risk of damage during transport.

Post-Harvest Care: Protect the Pins

After harvesting, inspect the bed for remaining pins and small mushrooms. Gently brush away any debris or loose substrate that might smother them, but avoid overhandling. Maintain consistent environmental conditions—humidity, temperature, and light—to encourage these pins to mature into the next flush. If you notice any signs of contamination, such as mold or off-colors, isolate the affected area and remove the contaminated substrate immediately. Proper post-harvest care ensures that the mycelium remains healthy and productive, setting the stage for future yields.

The Long-Term Perspective: Sustainable Harvesting Practices

Harvesting is not just about collecting mushrooms—it’s about nurturing a living system. By picking mature mushrooms carefully and respecting the mycelium, you foster a sustainable cycle of growth. Each harvest should leave the bed in a state that supports the next flush, minimizing stress on the fungus. For example, avoid harvesting all mushrooms at once; leave a few to drop spores naturally, replenishing the bed’s genetic diversity. This mindful approach ensures that your mushroom cultivation remains vibrant and prolific over time.

Exploring Florida's Forests: Are There Edible Mushrooms to Forage?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Edible mushrooms are typically grown using two main methods: substrate-based cultivation and outdoor log or stump cultivation. Substrate-based methods involve growing mushrooms on materials like straw, sawdust, or compost, while outdoor methods use natural wood logs or stumps inoculated with mushroom spawn.

Mushrooms require specific conditions to thrive, including a controlled environment with proper humidity (60-80%), temperature (55-75°F or 13-24°C), and adequate ventilation. Darkness or low light is also essential for most species, along with a sterile or clean growing medium to prevent contamination.

The time to harvest varies by species and growing method. For example, oyster mushrooms can be ready in 4-6 weeks, while shiitake mushrooms may take 6-12 months when grown on logs. Factors like temperature, humidity, and substrate quality also influence growth time.

Yes, edible mushrooms can be grown at home with minimal equipment. You’ll need mushroom spawn (the "seed" of fungi), a suitable substrate (e.g., straw, sawdust, or pre-made kits), a growing container, and a humid, temperature-controlled environment. Beginner-friendly species like oyster or lion’s mane are recommended for home cultivation.