Moss spores are produced through a specialized reproductive process in the life cycle of mosses, which are non-vascular plants belonging to the division Bryophyta. Unlike flowering plants, mosses reproduce via alternation of generations, involving both a gametophyte (haploid) and sporophyte (diploid) stage. Spores are generated during the sporophyte phase, where the sporangium, a capsule-like structure, develops at the tip of the seta (stalk). Within the sporangium, spore mother cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores. Once mature, the sporangium dries and splits open, releasing the spores into the environment. These lightweight spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals, eventually landing in suitable habitats where they germinate to grow into new gametophytes, thus continuing the life cycle. This process highlights the adaptability and resilience of mosses in diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporophyte Structure | Moss sporophytes are simple, unbranched structures growing from gametophytes. |

| Spore Production Site | Spores are produced within a capsule (sporangium) at the tip of the sporophyte (seta). |

| Capsule Structure | The capsule has a lid (operculum) that falls off when spores are mature, allowing dispersal. |

| Spore Type | Mosses produce haploid spores through meiosis in the sporophyte. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals after the operculum falls. |

| Gametophyte Dependency | Sporophytes are dependent on the gametophyte for nutrition and support. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spore production occurs in the diploid sporophyte phase of the life cycle. |

| Environmental Triggers | Spore release is often triggered by dry conditions to aid wind dispersal. |

| Spore Size | Moss spores are typically small (10-30 μm) for efficient wind dispersal. |

| Reproductive Strategy | Mosses rely on spores for asexual reproduction and colonization of new habitats. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporophyte Structure: Moss sporophytes have sporangia where spores develop via meiosis

- Meiosis Process: Spores form through meiosis, creating haploid cells in the sporangium

- Capsule Maturation: The sporangium matures, drying out to release spores effectively

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

- Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by light, moisture, and seasonal changes

Sporophyte Structure: Moss sporophytes have sporangia where spores develop via meiosis

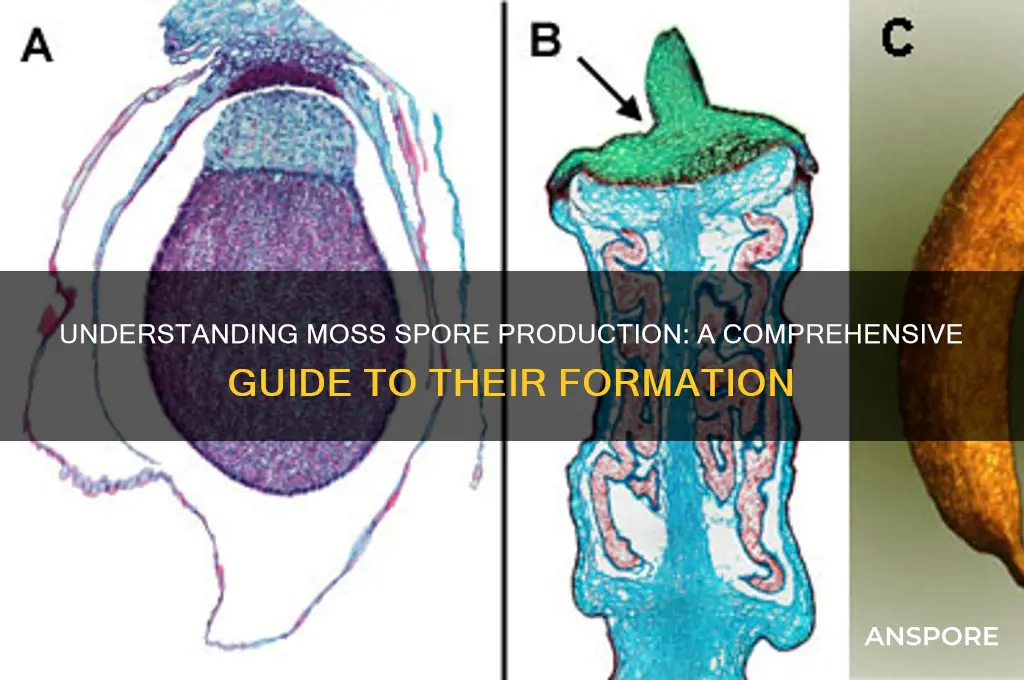

Moss sporophytes, the spore-producing structures in the life cycle of mosses, are marvels of simplicity and efficiency. Perched atop a slender seta (stalk), the sporophyte consists of a capsule-like structure called the sporangium, where the magic of spore production unfolds. This sporangium is not just a container; it’s a microcosm of genetic reshuffling, housing the cells that will undergo meiosis to create spores. Unlike the complex reproductive organs of flowering plants, moss sporophytes are streamlined, focusing solely on the essential task of spore development. This minimalist design reflects the moss’s adaptation to its environment, prioritizing survival over complexity.

The process within the sporangium is a textbook example of meiosis, the cellular division that reduces chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores. In mosses, this occurs in specialized cells called sporocytes, which line the inner walls of the sporangium. Each sporocyte divides twice, yielding four haploid spores. These spores are not just miniature versions of the parent; they carry unique genetic combinations, ensuring diversity in the next generation. This genetic variation is crucial for mosses, which often inhabit unpredictable environments where adaptability is key.

Understanding the structure of the sporophyte is essential for anyone cultivating mosses or studying their ecology. For instance, gardeners aiming to propagate mosses should note that the sporangium’s maturity is critical for spore collection. A mature sporangium will often have a lid-like structure called an operculum, which eventually falls off, releasing the spores. Timing is everything: collect spores just as the operculum begins to loosen, ensuring maximum viability. Practical tip: place a container beneath the sporophyte overnight to catch spores as they’re naturally released.

Comparatively, the sporophyte structure of mosses contrasts sharply with that of ferns or seed plants. While ferns also produce spores via meiosis, their sporangia are typically clustered into sori, often on the underside of leaves. Seed plants, on the other hand, bypass the spore stage entirely, producing seeds directly. Mosses, however, retain their ancestral spore-based reproduction, a trait shared with other bryophytes. This comparison highlights the evolutionary significance of moss sporophytes, offering a glimpse into the early stages of plant reproduction on Earth.

In conclusion, the sporophyte structure of mosses is a testament to nature’s ingenuity, combining simplicity with functionality. The sporangium, with its meiotic processes, ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, traits vital for moss survival. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or simply a nature enthusiast, appreciating this structure deepens your understanding of moss biology. Practical applications, such as spore collection for propagation, further underscore the importance of this tiny yet mighty organ in the moss life cycle.

Moss Spores' Protective Coat: Unveiling Nature's Tiny Armor Secrets

You may want to see also

Meiosis Process: Spores form through meiosis, creating haploid cells in the sporangium

Moss spores are the result of a precise and intricate process rooted in meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid cells. This process is essential for the life cycle of mosses, ensuring genetic diversity and the continuation of the species. Within the sporangium, a specialized structure located at the tip of the moss plant’s sporophyte, meiosis occurs, giving rise to spores that will eventually develop into new gametophyte plants. Understanding this mechanism provides insight into the resilience and adaptability of mosses in diverse environments.

The meiosis process begins with a diploid cell within the sporangium, which contains two sets of chromosomes. Through two rounds of division, meiosis I and meiosis II, this cell is transformed into four haploid cells, each carrying a single set of chromosomes. Meiosis I involves the pairing and separation of homologous chromosomes, while meiosis II divides the sister chromatids, ensuring each spore receives a unique genetic combination. This genetic shuffling is crucial for the survival of moss populations, allowing them to adapt to changing conditions and resist diseases.

Practical observation of this process can be facilitated by examining mature moss sporophytes under a microscope. Look for the capsule-like sporangium, often visible as a bulbous structure atop a slender seta (stalk). Dissection of the sporangium reveals the spore mother cells undergoing meiosis. For educational purposes, time-lapse microscopy can illustrate the dynamic nature of cell division, offering a tangible demonstration of how genetic diversity is generated. This hands-on approach enhances understanding of the meiosis process and its role in spore formation.

Comparatively, the meiosis-driven spore production in mosses contrasts with the asexual reproduction methods of some plants, such as vegetative propagation. While asexual methods produce genetically identical offspring, meiosis ensures genetic variation, a key advantage in unpredictable environments. This distinction highlights the evolutionary significance of spore formation through meiosis, as it balances stability with adaptability. For gardeners or ecologists, recognizing this difference underscores the importance of preserving moss habitats to maintain biodiversity.

In conclusion, the meiosis process within the sporangium is a cornerstone of moss reproduction, creating haploid spores that are both genetically diverse and viable. By reducing chromosome numbers and shuffling genetic material, meiosis ensures the long-term survival of moss species. Whether observed in a laboratory setting or appreciated in natural habitats, this process exemplifies the elegance of biological mechanisms. For those studying or cultivating mosses, understanding meiosis provides a deeper appreciation for these resilient plants and their ecological roles.

Do Mold Spores Circle Animals? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Capsule Maturation: The sporangium matures, drying out to release spores effectively

The sporangium, a capsule-like structure atop the moss's seta (stalk), undergoes a critical transformation during capsule maturation. This process is not merely about drying out; it’s a finely tuned mechanism ensuring spore dispersal at the optimal moment. As the sporangium matures, its walls thicken and dehydrate, creating internal tension. This tension is essential for the forceful ejection of spores when conditions are right, such as low humidity or gentle air movement. Think of it as nature’s spring-loaded mechanism, primed for precision release.

To visualize this, imagine a tiny, desiccated pod under a microscope. Its walls, once pliable, now resemble parchment paper—brittle yet resilient. This brittleness is key. When the capsule reaches its driest state, the smallest disturbance—a breeze, an insect’s touch—triggers the release of thousands of spores. For moss enthusiasts or researchers, observing this stage requires patience. Use a magnifying glass or low-power microscope to monitor the sporangium’s texture and color changes, noting when it transitions from glossy to matte, signaling readiness.

Practical tip: If you’re cultivating moss in a terrarium, mimic natural drying conditions by reducing misting frequency and increasing air circulation once the sporangia appear. Avoid direct sunlight, as it can scorch the delicate structures. For outdoor moss gardens, ensure the area is well-drained to prevent waterlogging, which delays maturation.

Comparatively, this process differs from seed dispersal in vascular plants, which often rely on external agents like animals or wind. Mosses, being non-vascular, must engineer their own dispersal mechanisms. The sporangium’s self-drying and tension-building are evolutionary marvels, showcasing how even the simplest plants solve complex problems. This efficiency is why moss spores can travel meters, even kilometers, on minimal energy.

In conclusion, capsule maturation is a masterclass in biological engineering. By understanding its mechanics, you can better appreciate—and replicate—the conditions mosses need to thrive. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a botanist, observing this stage offers insights into the resilience and ingenuity of these ancient plants.

Understanding Isolated Spore Syringes: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

Moss spores, the microscopic units of life, embark on remarkable journeys to ensure the survival and spread of their species. These journeys are facilitated by three primary dispersal mechanisms: wind, water, and animals. Each method is finely tuned to the environment in which the moss thrives, maximizing the chances of successful colonization. Wind dispersal, for instance, is particularly effective in open, exposed habitats where air currents can carry spores over vast distances. Lightweight and often equipped with wing-like structures, moss spores are designed to stay aloft, increasing their dispersal range. This mechanism is especially crucial for mosses growing in high altitudes or barren landscapes where other dispersal methods may be less reliable.

Water, on the other hand, plays a pivotal role in spore dispersal for mosses inhabiting moist environments, such as riverbanks, wetlands, and rainforests. Spores released into water currents can travel downstream, colonizing new areas along the way. This method is highly efficient in environments where water flow is consistent and predictable. For example, *Sphagnum* mosses, which dominate peatlands, rely heavily on water dispersal. Their spores are often released into standing water or slow-moving streams, ensuring they reach suitable habitats where they can germinate and grow. Interestingly, some moss spores are hydrophobic, allowing them to float on the water’s surface, further enhancing their dispersal potential.

Animal-mediated dispersal, though less common, is another fascinating mechanism employed by certain moss species. Spores may attach to the fur, feathers, or even the feet of animals as they move through the environment. This method is particularly effective in dense forests or understory habitats where wind and water dispersal are limited. For instance, small mammals like voles or birds may inadvertently carry spores from one location to another, facilitating colonization in otherwise inaccessible areas. Some mosses produce sticky or barbed spores that are more likely to adhere to passing animals, increasing the likelihood of successful dispersal.

Understanding these dispersal mechanisms is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications for conservation and horticulture. For example, when reintroducing moss species to degraded habitats, knowing their primary dispersal method can inform strategies for maximizing success. If a species relies on wind dispersal, planting it in open areas with good airflow is essential. Conversely, for water-dispersed species, ensuring access to flowing or standing water is critical. By mimicking natural dispersal mechanisms, we can enhance the survival and spread of mosses in restoration projects.

In conclusion, the dispersal of moss spores through wind, water, and animals is a testament to the adaptability and resilience of these ancient plants. Each mechanism is tailored to specific environmental conditions, ensuring that mosses can colonize diverse habitats. Whether carried on the breeze, swept along by a stream, or hitching a ride on an animal, these tiny spores embark on journeys that are as varied as they are vital. By studying these mechanisms, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for the natural world but also practical insights that can guide conservation efforts and sustainable practices.

Can Ceila Effectively Block Spores? Exploring Its Protective Capabilities

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by light, moisture, and seasonal changes

Mosses, those resilient pioneers of barren landscapes, don't simply release spores on a whim. Their sporulation, the process of producing and dispersing spores, is a finely tuned response to their environment. Imagine a conductor orchestrating a symphony, where light, moisture, and seasonal cues act as the musical score, guiding the timing and intensity of spore release.

Understanding these environmental triggers is crucial for anyone seeking to cultivate moss, study its ecology, or simply appreciate its remarkable adaptability.

Light, the Silent Maestro: Light acts as a primary signal, dictating when mosses prepare for reproduction. While some species thrive in shade, most require a specific light intensity and duration to initiate sporulation. Think of it as a wake-up call, prompting the moss to shift its energy from vegetative growth to spore production. Interestingly, the quality of light matters too. Red and far-red wavelengths, prevalent during specific times of day and year, can significantly influence sporulation rates. For instance, some mosses respond more readily to the longer days of spring, while others may require the shorter days of autumn to trigger spore development.

Research suggests that a minimum of 8-12 hours of indirect sunlight daily is optimal for many moss species, with some preferring even lower light levels.

Moisture, the Lifeblood of Sporulation: Water is essential for all stages of moss life, and sporulation is no exception. Adequate moisture is crucial for the development of spore capsules and the subsequent release of spores. Imagine trying to inflate a balloon without air – that's akin to a moss attempting sporulation without sufficient water. However, too much moisture can be detrimental, leading to rot and fungal infections. The key lies in maintaining a balance – a damp environment, not waterlogged. Misting moss regularly, ensuring good air circulation, and using a well-draining substrate are essential practices for successful sporulation.

For optimal results, aim for a humidity level of 60-80% and avoid allowing the moss to completely dry out.

Seasonal Changes, the Grand Cycle: Mosses are attuned to the Earth's seasonal rhythms, using temperature fluctuations and day length as cues for sporulation. In temperate regions, many mosses sporulate in spring or autumn, taking advantage of favorable conditions for spore dispersal and germination. Spring sporulation often coincides with melting snow and increased moisture, while autumn sporulation may be triggered by cooler temperatures and shorter days. These seasonal adaptations ensure that spores are released when conditions are most conducive for their survival and establishment.

By understanding these environmental triggers, we can create optimal conditions for moss sporulation, whether in a controlled laboratory setting or a naturalistic garden. Mimicking the light, moisture, and seasonal cues that mosses experience in their native habitats allows us to unlock their reproductive potential and appreciate the intricate dance between these ancient plants and their environment.

Are Black Mold Spores Black? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Color

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Moss spores are produced in structures called sporangia, which are located at the tips of the sporophytes (the diploid, spore-producing phase of the moss life cycle).

The production of moss spores is triggered by environmental conditions such as changes in light, humidity, and temperature, which signal the sporophyte to mature and release spores.

Spores are produced in the capsule (sporangium) of the sporophyte, which grows from the gametophyte (the green, leafy part of the moss).

Moss spores are dispersed through wind, water, or animals. The sporangium dries out and splits open, releasing the spores into the environment.

Moss spores are produced sexually through the fusion of gametes (sperm and egg) during fertilization, resulting in the development of the sporophyte, which then produces spores.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)