Yeast spores, essential for the survival and reproduction of yeast, are specifically called ascospores in many species, particularly in the ascomycete group, which includes common baker’s and brewer’s yeast. These ascospores are formed within a sac-like structure called an ascus during sexual reproduction, providing protection and enabling yeast to endure harsh environmental conditions. In contrast, some yeast species, like those in the basidiomycete group, produce basidiospores, though these are less common in the yeasts used in industrial or laboratory settings. Understanding the nomenclature and formation of these spores is crucial for fields such as biotechnology, brewing, and baking, where yeast’s reproductive mechanisms directly impact their functionality and applications.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ascospores: Formed in asci, sexual spores of ascomycetes, often eight per sac

- Basidiospores: Produced on basidia, sexual spores of basidiomycetes, common in mushrooms

- Blastospores: Asexual buds from yeast cells, common in budding yeast reproduction

- Chlamydospores: Thick-walled, resistant asexual spores for survival in harsh conditions

- Sporulation Process: Environmental triggers induce spore formation in yeast for survival

Ascospores: Formed in asci, sexual spores of ascomycetes, often eight per sac

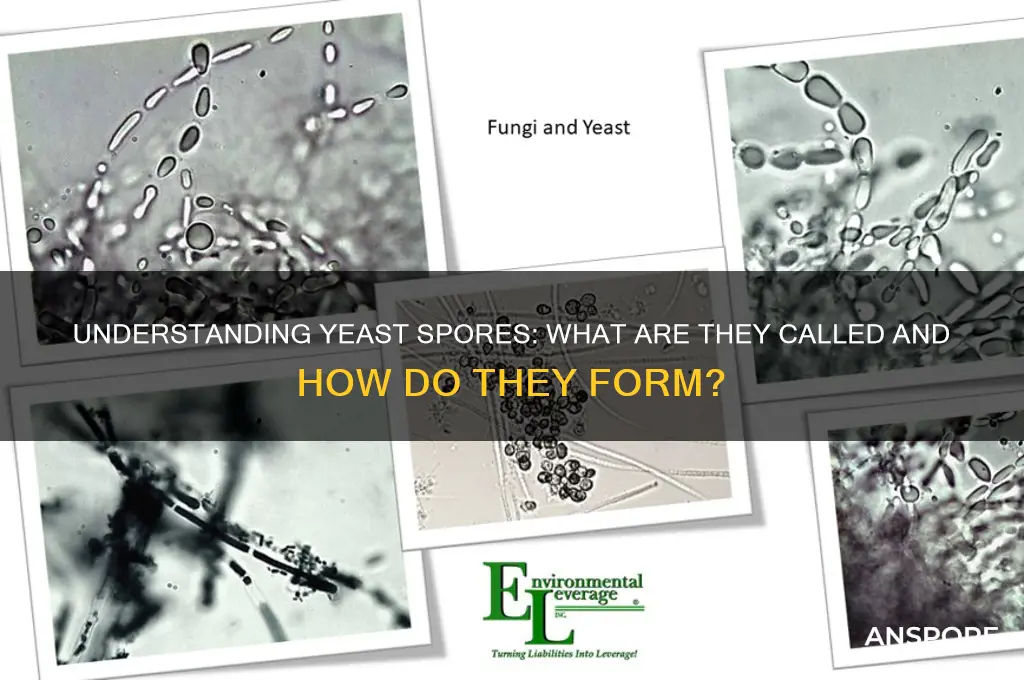

Yeast, a diverse group of eukaryotic microorganisms, reproduce through various means, including budding, fission, and spore formation. Among these, ascospores stand out as a distinctive feature of the Ascomycota phylum, one of the largest and most diverse groups of fungi. These sexual spores are not only a hallmark of ascomycetes but also play a crucial role in their life cycle, survival, and dispersal.

Formation and Structure

Ascospores are produced within a sac-like structure called an ascus, typically in groups of eight, though variations exist. This "eight per sac" arrangement is a defining characteristic, often visible under a microscope as a neat, orderly cluster. The ascus acts as a protective environment where karyogamy (fusion of haploid nuclei) and meiosis occur, resulting in genetically diverse ascospores. These spores are haploid, ensuring genetic variability, which is essential for adaptation and survival in changing environments.

Function and Significance

From an ecological perspective, ascospores serve as a survival mechanism. They are highly resistant to harsh conditions, such as desiccation, extreme temperatures, and UV radiation, allowing ascomycetes to persist in unfavorable environments. Once conditions improve, ascospores germinate, giving rise to new fungal colonies. This resilience makes ascospores critical for the long-term survival and dispersal of species like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) and *Aspergillus* spp., which are economically and ecologically significant.

Practical Applications

Understanding ascospores is not just academic; it has practical implications. In biotechnology, ascospores are used to study genetic recombination and fungal genetics. For instance, in yeast breeding programs, ascospores are isolated and cultured to develop strains with desirable traits, such as improved fermentation efficiency in brewing or baking. Additionally, ascospores are employed in mycological research to identify and classify ascomycetes, aiding in biodiversity studies and pathogen detection.

Cautions and Considerations

While ascospores are beneficial in controlled settings, they can pose challenges in industrial and clinical contexts. For example, airborne ascospores of certain molds can contaminate food production facilities or cause allergic reactions in humans. Proper ventilation, filtration, and monitoring are essential to mitigate these risks. In laboratories, handling ascospores requires sterile techniques to prevent cross-contamination and ensure accurate experimental results.

In summary, ascospores are a fascinating and functionally vital aspect of ascomycete biology. Their formation within asci, typically in groups of eight, underscores their role in genetic diversity, survival, and dispersal. Whether in nature, industry, or research, these spores exemplify the intricate strategies fungi employ to thrive in diverse environments.

Milky Spore Grub Control: Effective Lawn Treatment or Myth?

You may want to see also

Basidiospores: Produced on basidia, sexual spores of basidiomycetes, common in mushrooms

Yeast spores, often referred to as ascospores in many species, are primarily asexual structures like conidia or blastospores. However, when discussing the broader fungal kingdom, basidiospores emerge as a distinct and fascinating counterpart. Produced on basidia, these sexual spores are the hallmark of basidiomycetes, a phylum encompassing mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts. Unlike yeast’s asexual reproduction, basidiospores are the result of a complex sexual lifecycle, making them a cornerstone of fungal diversity and ecology.

To understand basidiospores, imagine a microscopic club-shaped structure—the basidium—perched on the gills or pores of a mushroom cap. Each basidium typically bears four spores, held aloft like tiny balloons ready to drift away. This aerial dispersal is critical for the fungus’s survival, allowing it to colonize new substrates and evade competition. For instance, a single mature mushroom can release millions of basidiospores in a single night, carried by wind currents to distant locations. This efficiency explains why mushrooms often appear in clusters after rain, as spores germinate in favorable conditions.

From a practical standpoint, understanding basidiospores is essential for mycologists, farmers, and even home gardeners. For example, shiitake and oyster mushrooms are cultivated by inoculating substrate with basidiospores, which then grow into fruiting bodies. However, not all basidiomycetes are beneficial; rust fungi produce basidiospores that devastate crops like wheat and soybeans. Monitoring spore counts in the air can predict outbreaks, allowing farmers to take preventive measures. For hobbyists, collecting basidiospores for cultivation requires sterile techniques, such as using a laminar flow hood to avoid contamination.

Comparatively, while yeast spores are often associated with fermentation and baking, basidiospores play a pivotal role in ecosystems as decomposers and symbionts. Yeast’s asexual spores are quick to reproduce but lack genetic diversity, whereas basidiospores, being sexual, introduce genetic recombination, enhancing adaptability. This distinction highlights the evolutionary sophistication of basidiomycetes, which have thrived for over 400 million years. For instance, the honey mushroom (*Armillaria ostoyae*) uses basidiospores to form one of the largest living organisms on Earth, spanning 37 acres in Oregon.

In conclusion, basidiospores are not just spores—they are the lifeblood of basidiomycetes, driving their ecological and economic impact. Whether you’re a scientist studying fungal lifecycles, a farmer combating rust, or a mushroom enthusiast cultivating gourmet varieties, understanding these spores is key. Their production on basidia, their role in sexual reproduction, and their dispersal mechanisms make them a fascinating subject within the broader question of how yeast and fungal spores are named and function.

Are Spores Legal in Virginia? Understanding the Current Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Blastospores: Asexual buds from yeast cells, common in budding yeast reproduction

Yeast, a microscopic fungus, reproduces through various methods, but one of the most common and efficient ways is via asexual budding, producing structures known as blastospores. These buds emerge as small outgrowths from the parent cell, eventually detaching to form new, genetically identical yeast cells. This process is particularly prevalent in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, the species widely used in baking, brewing, and biotechnology. Understanding blastospores is crucial for optimizing yeast-dependent industries, as their formation directly impacts fermentation rates, biomass production, and product quality.

Formation and Mechanism

Blastospore development begins with the accumulation of cytoplasm and organelles in a localized area of the parent cell, forming a bud. As the bud grows, it replicates the nucleus through mitosis, ensuring the new cell contains a complete set of genetic material. The bud remains attached to the parent cell until it reaches maturity, at which point a septum forms, separating the two cells. This process repeats rapidly under favorable conditions, with a single yeast cell capable of producing multiple blastospores in a short period. For instance, in optimal laboratory conditions (30°C, pH 4–6, and nutrient-rich media), *S. cerevisiae* can double its population every 90 minutes through budding.

Practical Applications and Optimization

In industrial settings, maximizing blastospore production is key to enhancing yeast performance. For brewers, maintaining a consistent temperature (18–25°C for ale, 10–15°C for lager) and ensuring adequate oxygen supply during the initial growth phase promotes healthy budding. Bakers can encourage robust yeast activity by using a starter dough with a hydration level of 60–70% and allowing it to ferment for 8–12 hours. In biotechnology, controlling nutrient availability—particularly carbon and nitrogen sources—can significantly influence blastospore formation. For example, a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 5:1 is ideal for maximizing biomass yield in yeast cultures.

Challenges and Cautions

While blastospores are efficient for rapid reproduction, their asexual nature limits genetic diversity, making yeast populations vulnerable to environmental changes or stressors. Overcrowding in cultures can lead to nutrient depletion and the accumulation of toxic byproducts like ethanol, inhibiting budding. To mitigate this, regular monitoring of pH, dissolved oxygen, and cell density is essential. Additionally, avoiding extreme temperatures (above 37°C or below 4°C) prevents cellular stress that could halt bud formation. For homebrewers or bakers, using fresh yeast and avoiding prolonged storage ensures optimal budding activity.

Comparative Advantage Over Other Spores

Unlike sexual spores (ascospores) produced through meiosis, blastospores offer a faster and more resource-efficient means of reproduction. While ascospores provide genetic variation beneficial for long-term survival, blastospores are ideal for rapid proliferation in stable environments. This makes them particularly valuable in controlled industrial processes where consistency is paramount. For example, in beer production, the predictable growth of blastospores ensures consistent fermentation profiles, whereas ascospores might introduce variability. By focusing on conditions that favor budding, industries can harness the full potential of yeast’s asexual reproduction for scalable and reliable outcomes.

Glutaraldehyde's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Chlamydospores: Thick-walled, resistant asexual spores for survival in harsh conditions

Yeast, often celebrated for its role in fermentation, harbors a lesser-known survival strategy: chlamydospores. These thick-walled, asexual spores are the yeast’s answer to adversity, enabling it to endure conditions that would otherwise prove fatal. Unlike their vegetative counterparts, chlamydospores are not for growth or reproduction in favorable environments; they are dormant fortresses, designed to withstand extremes of temperature, desiccation, and chemical stress. This resilience makes them a fascinating subject in both microbiology and biotechnology.

Consider the formation of chlamydospores as a survival tactic. When yeast cells detect environmental stressors, such as nutrient depletion or temperature fluctuations, they initiate a transformation. A single cell or a portion of a hypha thickens its cell wall, accumulates storage compounds like lipids and carbohydrates, and enters a quiescent state. This process is not merely a passive response but a highly regulated metabolic shift, ensuring the spore’s longevity. For instance, *Candida albicans* and *Fusarium* species are known to produce chlamydospores under stress, showcasing their adaptability across diverse fungal lineages.

The structure of chlamydospores is as intriguing as their function. Their thick cell walls, often layered with melanin or other protective compounds, act as a barrier against external threats. This fortification allows them to remain viable for years, even in soil or other inhospitable environments. In industrial settings, this durability is both a challenge and an opportunity. While chlamydospores can contaminate food processing equipment due to their resistance to cleaning agents, they also inspire the development of bio-preservatives and stress-tolerant strains for fermentation processes.

For those working with yeast in laboratories or industries, understanding chlamydospores is crucial. To induce their formation, subject yeast cultures to controlled stress conditions, such as gradual nutrient deprivation or exposure to suboptimal temperatures. However, caution is advised: once formed, chlamydospores are notoriously difficult to eradicate. Standard sterilization methods, like heat or chemical treatment, often fail to eliminate them. Instead, prolonged exposure to extreme conditions or specialized antifungal agents may be required.

In conclusion, chlamydospores exemplify yeast’s remarkable ability to adapt and survive. Their thick-walled structure and dormant state make them a double-edged sword—a challenge in contamination control but a model for engineering resilient microbial systems. By studying these spores, scientists can unlock new strategies for preserving yeast cultures, combating fungal pathogens, and harnessing their potential in biotechnology. Whether in the lab or the field, chlamydospores remind us of the ingenuity embedded in even the smallest organisms.

Can Fungal Spores Duplicate? Unveiling the Science Behind Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process: Environmental triggers induce spore formation in yeast for survival

Yeast, a unicellular fungus, employs sporulation as a survival strategy in response to environmental stressors. This process, known as sporulation, transforms vegetative cells into highly resilient spores capable of enduring harsh conditions. Unlike bacterial spores, yeast spores, termed ascospores, are formed through a specialized sexual reproduction process called ascospore formation. This distinction is crucial, as it highlights the unique mechanism yeast employs to ensure survival.

Understanding the sporulation process in yeast is not merely academic; it has practical implications in industries like brewing and baking, where yeast viability directly impacts product quality.

The sporulation process in yeast is a complex, multi-step journey triggered by specific environmental cues. Primarily, nutrient deprivation, particularly nitrogen limitation, acts as the primary signal for yeast cells to initiate sporulation. This stressor prompts a cascade of intracellular changes, including DNA replication, meiosis, and ultimately, the formation of four haploid spores within a protective ascus. Interestingly, this process is not universal among all yeast species. For instance, the widely studied *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* readily undergoes sporulation, while other species like *Candida albicans* lack this ability.

This variability underscores the importance of understanding the specific environmental triggers and genetic factors influencing sporulation across different yeast species.

The formation of ascospores is a testament to yeast's remarkable adaptability. These spores exhibit significantly enhanced resistance to extreme temperatures, desiccation, and other environmental insults compared to their vegetative counterparts. This resilience stems from several factors, including a thickened cell wall, altered membrane composition, and the accumulation of protective molecules like trehalose. The ability to enter a dormant spore state allows yeast to survive periods of adversity, ensuring their long-term survival and contributing to their ecological success.

For example, in the brewing industry, understanding sporulation can help optimize fermentation processes by ensuring the viability of yeast cultures during storage and transportation.

While sporulation is a vital survival mechanism, it's not without its vulnerabilities. Certain environmental conditions, such as exposure to high concentrations of ethanol or extreme pH levels, can inhibit sporulation or damage spores. Additionally, the process itself is energetically costly, requiring significant resources from the yeast cell. This trade-off between survival and energy expenditure highlights the delicate balance yeast must maintain in response to environmental challenges.

In conclusion, the sporulation process in yeast, triggered by environmental stressors, is a fascinating example of microbial adaptation. Understanding the specific triggers, mechanisms, and implications of this process not only deepens our knowledge of yeast biology but also holds practical value in various industries. By appreciating the intricacies of sporulation, we gain valuable insights into the remarkable strategies microorganisms employ to thrive in a constantly changing world.

Can You Mod Spore on Steam? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yeast spores are called ascospores in the case of ascomycete yeasts, which are produced within a sac-like structure called an ascus.

No, not all yeast spores are ascospores. Some yeasts, like basidiomycete yeasts, produce basidiospores, which are formed on a structure called a basidium.

No, not all yeast species produce spores. Many yeasts reproduce primarily through budding, and only certain species under specific conditions (e.g., stress or nutrient depletion) form spores.

Yeast spores serve as a survival mechanism, allowing yeasts to withstand harsh environmental conditions such as heat, drought, or lack of nutrients. They can remain dormant until favorable conditions return.

Yeast spores are thicker-walled, more resistant, and metabolically dormant compared to vegetative cells, which are actively growing and dividing through budding or fission.