Mushrooms release billions of spores, which are microscopic in size. These spores are launched at varying speeds and travel over different distances, depending on the mushroom species. The size of a mushroom spore is strongly related to the time of fruiting, with larger spores containing more water and nutrients, which are essential for germination and initial growth. Birds are also known to contribute to the long-distance dispersal of fungal spores, aiding the spread of invasive species across continents.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Speed of spore discharge | 0.1 to 1.8 m/s |

| Travel distance | 0.04 to 1.26 mm |

| Spore size | 3.5 x 0.5 µm to 34 x 28 µm |

| Spore volume | 0.5 fL to 14 pL |

| Spore mass | 0.6 pg to 17 ng |

| Spore discharge mechanism | Ballistospore |

| Spore dispersal mechanism | Wind |

| Spore shape | Ellipsoid |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mushrooms with larger spores have more nutrients and water

Mushrooms are fascinating organisms that play a crucial role in nature's ecosystem. While they might seem simple, these fungi have a complex life cycle that begins with spores. These spores are microscopic particles, ranging from 3 to 12 microns in size, and they are the reproductive units for fungi. They contain all the genetic material necessary to grow new mushrooms. The size of these spores is not just a coincidence; it is influenced by the time of fruiting and the environmental conditions in which the mushrooms develop.

In autumn, when most mushrooms fruit, the climate varies from the early season to late autumn. Early in the season, higher average air temperatures and lower precipitation levels are typical. These conditions pose a challenge for the survival of spores, as they are more susceptible to desiccation or drying out. To counter this, larger spores are produced, as they contain more water and nutrients, which are essential for the germination process and the initial growth phase.

The relationship between spore size and time of fruiting is evident in the findings from Norway. On average, a doubling of spore size corresponded to an earlier fruiting time by three days. This pattern is observed in the spatial distribution of small and large-spored species across Norway. Small-spored species are more prevalent in the oceanic parts, benefiting from the moister climate, while large-spored species dominate in the more continental regions.

The moisture content in the environment plays a critical role in the life cycle of mushrooms. Fungi require water at all stages of their life, and mushrooms, in particular, consist of approximately 90% water. Water is necessary for the breakdown of organic matter by enzymes and the subsequent absorption of nutrients. When water is scarce, fungi have mechanisms to ensure sufficient water uptake, such as hydraulic redistribution and osmotic regulation.

In conclusion, mushrooms with larger spores have more nutrients and water, which is a crucial advantage in drier and warmer early-season conditions. This adaptation ensures the successful germination and initial growth of the primary mycelia. The relationship between spore size and fruiting time, influenced by moisture availability, is a fascinating aspect of mushroom biology that highlights their intricate connection with the environment.

Mushrooms: When Are They Past Their Prime?

You may want to see also

Wind is the primary dispersal mechanism for most fungal spores

The launch distance of ballistospores is limited by the increasing time required for the expansion of larger drops. The rate of expansion of Buller’s drop follows an asymptotic curve. This may be due to a reduction in the rate of condensation of water molecules on the drop surface as expansion dilutes the hygroscopic compounds dissolved in the fluid. Sugars and sugar alcohols (mannitol) have been identified in washings from spore deposits and from Buller’s drops collected in micropipets, but their release is not understood.

The microscopic size of spores enables them to be transported by even slow flows of air, but it also severely limits the distance that they may travel ballistically. Launched at a speed of 8.4 m/s, the 12 μm long spores of the pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum would be decelerated to rest after traveling less than 3 mm. In response to this constraint, fungi have evolved multiple adaptations to maximize spore range. For example, spores that cohere during launch benefit from increased inertia, while individually ejected spores may be shaped to minimize drag.

The ability to manipulate the local fluid environment to enhance spore dispersal is a previously overlooked feature of the biology of fungal pathogens. Some apothecial species, including the pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, disperse with astonishing rapidity between ephemeral habitats. By synchronizing the ejection of thousands of spores, these fungi create a flow of air that carries spores through the nearly still air surrounding the apothecium, around intervening obstacles, and to atmospheric currents and new infection sites. High-speed imaging shows that synchronization is self-organized and likely triggered by mechanical stresses.

Mushroom Hunting: Foraging Wild Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Birds can also aid in the long-distance dispersal of spores

Mushrooms release billions of microscopic spores, which are spread into the air. While wind is the primary dispersal mechanism for most fungal spores, birds can also aid in the long-distance dispersal of spores. Birds have been known to disperse viable spores via mycophagy, or the consumption of fungi. Birds may also act as cryptic but critical fungal dispersal agents in ecosystems.

Birds are known to disperse spores through their feathers, which can transport spores over large distances. Flying animals, such as birds, are known to serve as fungal vectors, and there is significant evidence for birds as mediators of fungal dispersal, especially of pathogens. Birds contribute significantly to long-distance fungal dispersal, potentially aiding the establishment of invasive species across continents.

The role of birds in spore dispersal is often overlooked, and they are considered cryptic vectors. Understanding the full range of dispersal mechanisms is critical, as climate change drives shifts in species distributions and increases vector activity. Birds may disperse spores either internally or externally, and spores sheltered deep within feathers are potentially protected from harsh environments as they move over large distances.

The size of mushroom spores varies, with larger spores containing more water and nutrients, which are essential during the germination process and the initial growth phase. Smaller spores are more prevalent in areas with a moister climate, while larger spores are typical of more continental parts. The launch velocity of spores also varies, with basidiospores being launched at speeds ranging from 0.1 to 1.8 m/s and travelling over distances of 0.04 to 1.26 mm.

Sliced Mushrooms: Who Was the Culinary Pioneer?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The shape of mushroom spores affects the shape of water droplets

Mushrooms release billions of spores into the air each year. These spores are tiny, microscopic even, and are used for the mushroom's own reproduction. However, these spores also have a secondary function: they help to collect water vapour in the air and form rain clouds in the sky.

When spores are released from the gills of mushrooms, they are accompanied by a droplet of fluid on the cell surface. This fluid is formed by the condensation of water vapour on the spore surface, stimulated by the secretion of mannitol and other hygroscopic sugars. This droplet evaporates once the spore is airborne, but in humid air, new droplets reform on the spores. The spores act as nuclei for the formation of large water drops in clouds.

The shape of the spore affects the shape of the water droplet that forms on it. Buller's drop forms on the very tip of the mushroom spore. As the drop collects more water vapour, it combines with the smaller adaxial drop on the other side of the spore. The merging of these two droplets gives the spore momentum, launching it into the atmosphere. The shape of the spore determines the size and shape of Buller's drop and the adaxial drop, which in turn affects the trajectory and launch speed of the spore.

Additionally, larger spores contain more water and nutrients, which are essential during the germination process and the initial growth phase. The spatial distribution of mushroom species with small and large spores may be related to water availability for establishment, with species with smaller spores being more prevalent in areas with moister climates.

Portabella Mushrooms: Carbohydrate Content in a Cup

You may want to see also

Larger mushroom species have larger spores

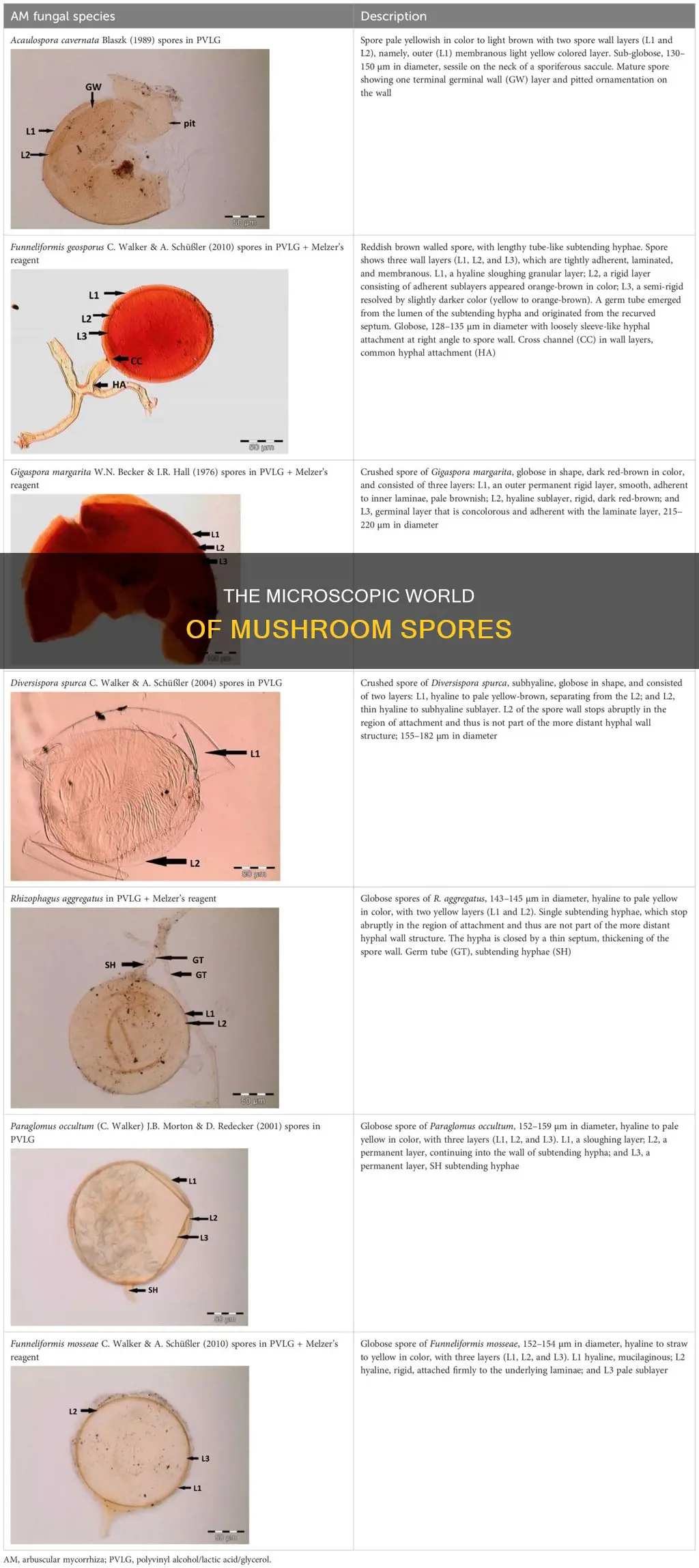

The size of a mushroom spore varies across different mushroom species, and there is a general relationship between the size of the mushroom and the size of its spores: larger mushroom species tend to have larger spores. This correlation is not surprising, as spore size is influenced by the volume of spores that a mushroom can produce and disperse effectively for the propagation of its species.

The giant puffball mushroom, for example, which can reach impressive sizes, also produces relatively large spores. These spores are typically spherical or oval and can measure up to 5 micrometers in diameter. In contrast, the spores of the honey mushroom, which is a much smaller fungus, are only about 3-5 micrometers in length.

Another example is the Amanita genus, which includes some of the most recognizable and iconic mushrooms, such as the fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*) and the death cap (*Amanita phalloides*). These mushrooms can reach considerable sizes, and their spores are also on the larger side. For instance, the spores of *A. muscaria* typically measure around 8-12 micrometers in length, while those of *A. phalloides* can be even larger, reaching up to 15 micrometers.

On the smaller end of the spectrum, we have mushrooms like the enoki (*Flammulina velutipes*) and oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus* spp.). These fungi typically grow to modest sizes, and their spores are correspondingly smaller. Enoki mushroom spores are elongated and cylindrical, measuring approximately 5-8 micrometers in length, while oyster mushroom spores are similarly sized, ranging from 4-7 micrometers.

While there are exceptions to every rule, the trend holds that larger mushroom species tend to have larger spores. This relationship is likely influenced by the biology of spore dispersal and the need to ensure effective propagation. Larger spores may have a greater chance of successful germination and the development of new mushroom fruiting bodies, contributing to the survival and dispersal strategies of these fascinating organisms.

How Mushrooms Sprout: A Fungi's Life Cycle

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom spores are microscopic, with the smallest recorded basidiospores from the Hyphodontia latitans (Hymenochaetales) species measuring 3.5 x 0.5 µm.

Mushroom spores don't travel very far. Studies show that basidiospores travel at speeds varying from 0.1 to 1.8 m/s and distances of 0.04 to 1.26 mm, which is the equivalent of 9 to 63 times the length of the spores.

On average, bigger mushrooms have bigger spores—about 9% longer, 9% wider, and 33% more voluminous. However, this is not always the case, as some species of larger mushrooms produce smaller spores.