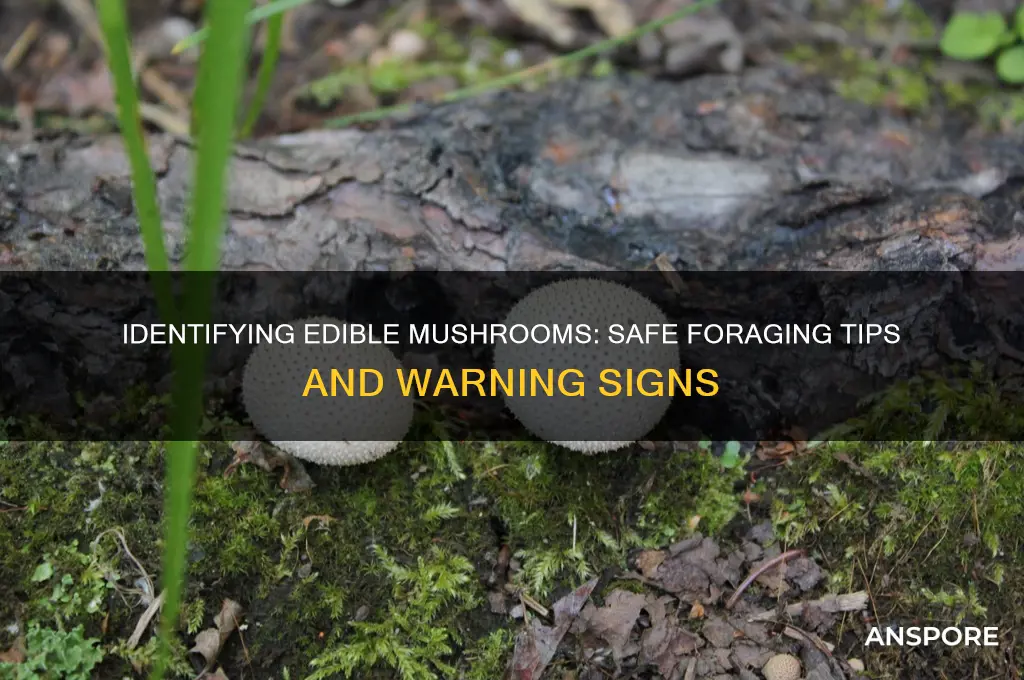

Determining whether mushrooms are edible requires careful observation and knowledge, as many species closely resemble each other, with some being toxic or even deadly. Key factors to consider include the mushroom’s physical characteristics, such as its cap shape, color, gills, stem, and presence of a ring or volva. Additionally, noting its habitat, smell, and any changes in color when bruised can provide crucial clues. However, relying solely on visual identification or folklore methods like bugs eating it or cooking to neutralize toxins is risky. Consulting a reliable field guide, using mushroom identification apps, or seeking advice from an experienced mycologist is strongly recommended to ensure safety. When in doubt, it’s best to avoid consumption altogether.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Color and Shape: Bright colors, unique shapes often indicate toxicity; plain colors, typical shapes may be safe

- Gill and Spore Check: White or brown spores, attached gills are safer; green/black spores, free gills are risky

- Bruising and Smell: Edible mushrooms rarely bruise or have strong odors; toxic ones often do

- Habitat and Location: Avoid mushrooms near polluted areas or certain trees; grasslands are safer

- Taste and Touch: Never taste; avoid if skin irritates or burns upon contact

Color and Shape: Bright colors, unique shapes often indicate toxicity; plain colors, typical shapes may be safe

Mushrooms with vivid reds, bright yellows, or striking whites often serve as nature’s warning signs. These bold colors, particularly when paired with contrasting patterns like spots or streaks, frequently indicate the presence of toxins. For instance, the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), with its iconic red cap and white dots, is both eye-catching and poisonous. While not all brightly colored mushrooms are deadly, their flamboyant appearance evolved as a defense mechanism to deter predators, including humans. If you encounter a mushroom that looks like it belongs in a fairy tale, proceed with caution—its beauty may mask danger.

In contrast, mushrooms with muted tones—think earthy browns, soft grays, or pale creams—are more likely to be safe for consumption. These plain colors often correlate with species that rely on blending into their environment rather than standing out. For example, the common Button Mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), found in grocery stores, has a simple white or light brown cap and a straightforward shape. However, color alone is not a definitive test; some toxic mushrooms, like the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*), mimic harmless brown species. Always cross-reference with other identification methods.

Shape plays an equally critical role in assessing edibility. Mushrooms with typical forms—a rounded cap, a central stem, and gills or pores underneath—are more likely to be safe. These familiar structures align with well-known edible varieties, such as the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*), which has a gently undulating cap and forked gills. Conversely, mushrooms with unusual shapes, like star-like caps, bulbous bases, or intricate frills, often belong to toxic families. The Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), while edible and unique in appearance, is an exception, highlighting the need for species-specific knowledge.

To apply this knowledge in the field, start by observing the mushroom’s overall appearance. If it resembles a textbook example of a safe species—plain colors, standard shape—it may warrant further investigation. However, never rely on color and shape alone. Use a field guide or identification app to confirm details like spore color, habitat, and odor. For beginners, avoid collecting mushrooms with bright colors or bizarre shapes altogether. When in doubt, consult an expert or leave the mushroom undisturbed—misidentification can have severe consequences.

While color and shape provide valuable initial clues, they are not foolproof indicators of edibility. Nature’s exceptions, like the edible but brightly colored Vermilion Waxcap (*Hygrocybe miniata*), remind us of the complexity of mushroom identification. Treat these guidelines as a starting point, not a definitive rule. Always prioritize caution, especially if you lack experience. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms but to do so safely, ensuring a rewarding and risk-free foraging experience.

Delicious Butternut Squash and Mushroom Recipe Ideas to Try Today

You may want to see also

Gill and Spore Check: White or brown spores, attached gills are safer; green/black spores, free gills are risky

Mushrooms with white or brown spores and attached gills are generally safer to consume, while those with green or black spores and free gills should raise red flags. This simple observation can be a critical first step in distinguishing edible mushrooms from their toxic counterparts. The spore color and gill attachment are easily observable features that provide valuable clues about a mushroom's identity and potential safety.

To perform a gill and spore check, start by examining the underside of the mushroom cap. Gently lift the cap to reveal the gills, which are the thin, closely spaced structures that produce spores. In edible mushrooms like the common button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) or the chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), the gills are typically attached to the stem and produce white or brown spores. These spores are often released in a uniform, consistent color, which can be observed by placing the cap on a piece of white paper for a few hours. If the spores that accumulate on the paper are white or brown, it’s a positive sign, though not a definitive guarantee of edibility.

In contrast, mushrooms with green or black spores, such as the deadly Galerina marginata or the poisonous Cortinarius species, are highly risky. These colors often indicate the presence of toxins that can cause severe illness or even be fatal. Additionally, free gills—those that are not firmly attached to the stem and can easily be separated—are another warning sign. Free gills are common in many toxic species, including the notorious Amanita genus, which contains some of the most poisonous mushrooms in the world.

While the gill and spore check is a useful tool, it’s essential to approach it with caution. Not all edible mushrooms have white or brown spores, and not all toxic ones have green or black spores. For instance, the edible oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) has white spores but can be confused with the toxic Omphalotus olearius, which also has white spores but emits a bioluminescent glow. Always cross-reference your findings with other identification features, such as cap shape, stem characteristics, and habitat.

Practical tips for conducting a gill and spore check include using a magnifying glass to examine gill attachment and spore color more closely. If you’re unsure, avoid consuming the mushroom altogether. Remember, foraging for mushrooms should always be done with a field guide or an experienced guide, and when in doubt, throw it out. The gill and spore check is a valuable technique, but it’s just one piece of the puzzle in the complex art of mushroom identification.

Transforming Magic Mushrooms: A Guide to Creating Psilocybin Powder

You may want to see also

Bruising and Smell: Edible mushrooms rarely bruise or have strong odors; toxic ones often do

A mushroom's reaction to touch can be a subtle yet crucial indicator of its edibility. When you gently press or cut into a mushroom, observe whether it bruises or discolors. Edible mushrooms typically maintain their original color and texture, showing little to no change. In contrast, toxic mushrooms often reveal their true nature through bruising—a telltale sign that should immediately raise caution. For instance, the deadly Amanita species, known for their toxicity, will quickly turn yellow or brown when handled, serving as a natural warning system.

The sense of smell is another powerful tool in your mushroom-hunting arsenal. Edible mushrooms generally have mild, pleasant, or earthy aromas, if any scent at all. Toxic varieties, however, may emit strong, unpleasant odors, ranging from foul and putrid to sharply chemical. Imagine the difference between the fresh, woody scent of a chanterelle and the acrid, bleach-like smell of the toxic Sulphur Tuft mushroom. This distinct olfactory contrast can be a critical factor in distinguishing between a delicious meal and a dangerous mistake.

Here's a practical approach: When examining a mushroom, apply gentle pressure to its cap and stem, noting any color changes. Then, carefully smell the mushroom, ensuring you don't inhale too deeply, as some toxic spores can be harmful if inhaled. If the mushroom bruises significantly or emits a strong, off-putting odor, it's best to err on the side of caution and avoid consumption. This simple test, combined with other identification methods, can significantly reduce the risk of accidental poisoning.

While bruising and smell are valuable indicators, it's essential to remember that not all toxic mushrooms will exhibit these traits, and some edible ones might show minor bruising. Therefore, this method should be used in conjunction with other identification techniques, such as examining spore prints, gill attachment, and habitat. For beginners, it's advisable to start with easily identifiable species and always consult a local mycological society or an experienced forager when in doubt. The world of mushrooms is fascinating but demands respect and careful study to fully appreciate its edible delights.

Growing Organic Shiitake Mushrooms Indoors: A Beginner's Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Habitat and Location: Avoid mushrooms near polluted areas or certain trees; grasslands are safer

Mushrooms absorb their surroundings, making habitat a critical factor in edibility. Those growing near industrial areas, busy roads, or agricultural fields may accumulate toxins like heavy metals or pesticides. For instance, a study in *Environmental Science & Technology* found mushrooms near highways contained lead levels unsafe for consumption. If you spot mushrooms in such polluted zones, steer clear—no matter how tempting they look.

Certain trees also signal caution. Mushrooms forming symbiotic relationships with specific species, like the deadly Amanita growing near oaks or birches, can be deceptive. While not all tree-associated mushrooms are toxic, the risk is higher. Grasslands, on the other hand, offer a safer bet. Open fields with minimal pollution and fewer competing species reduce the likelihood of encountering dangerous varieties. Think of grasslands as the "beginner’s zone" for foragers.

To minimize risk, follow this rule: avoid mushrooms within 500 meters of major roads, factories, or farms. If you’re near trees, research the common fungi associated with them beforehand. For example, the Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom, often found near hardwoods, resembles chanterelles but causes severe gastrointestinal distress. When in doubt, leave it out.

Practical tip: Carry a portable soil testing kit to check for contaminants if you’re unsure about the area. While not foolproof, it adds an extra layer of safety. Remember, edibility isn’t just about appearance—it’s about where the mushroom calls home. Choose habitats wisely, and you’ll reduce the odds of a toxic encounter.

Can Porcini Mushrooms Cause Illness? Risks and Safe Consumption Tips

You may want to see also

Taste and Touch: Never taste; avoid if skin irritates or burns upon contact

A common misconception about identifying edible mushrooms is that tasting a small amount can help determine their safety. This is a dangerous myth. Ingesting even a tiny portion of a toxic mushroom can lead to severe poisoning, organ failure, or death. The toxins in poisonous mushrooms are not always bitter or unpleasant, so taste is an unreliable indicator. For instance, the deadly Amanita species can have a mild, nutty flavor that might deceive even the most cautious forager. Therefore, the cardinal rule is simple: never taste a wild mushroom to test its edibility.

Beyond taste, some advocate for using touch as a test—rubbing a mushroom on the skin to check for irritation or burns. While it’s true that certain toxic mushrooms contain compounds that can cause skin reactions, this method is far from foolproof. For example, the toxic Jack-O-Lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*) can cause skin irritation in sensitive individuals, but many people show no reaction at all. Conversely, some edible mushrooms, like the Oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), can also irritate the skin of those with allergies. Relying on skin contact as a test introduces unnecessary risk and confusion, especially for beginners.

The takeaway is clear: neither taste nor touch should be used as reliable methods for identifying edible mushrooms. Instead, focus on visual identification, such as examining the mushroom’s cap, gills, stem, and spore print. Consult field guides or expert foragers, and when in doubt, err on the side of caution. Practical tips include carrying a notebook to document findings and attending local mycology club meetings to learn from experienced identifiers. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms but to do so safely and responsibly.

Creative Uses for Shiitake Mushroom Stems: Delicious Recipes & Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Visual identification alone is not reliable, as many toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones. Key features like color, shape, and gills can be misleading. Always consult a field guide or expert for accurate identification.

No, there are no universal signs. Some edible mushrooms have toxic look-alikes, and some toxic mushrooms lack obvious warning signs like bright colors or unpleasant odors.

No, home tests like the silver spoon or onion methods are myths and do not reliably indicate edibility. Always rely on scientific identification methods or consult a mycologist.