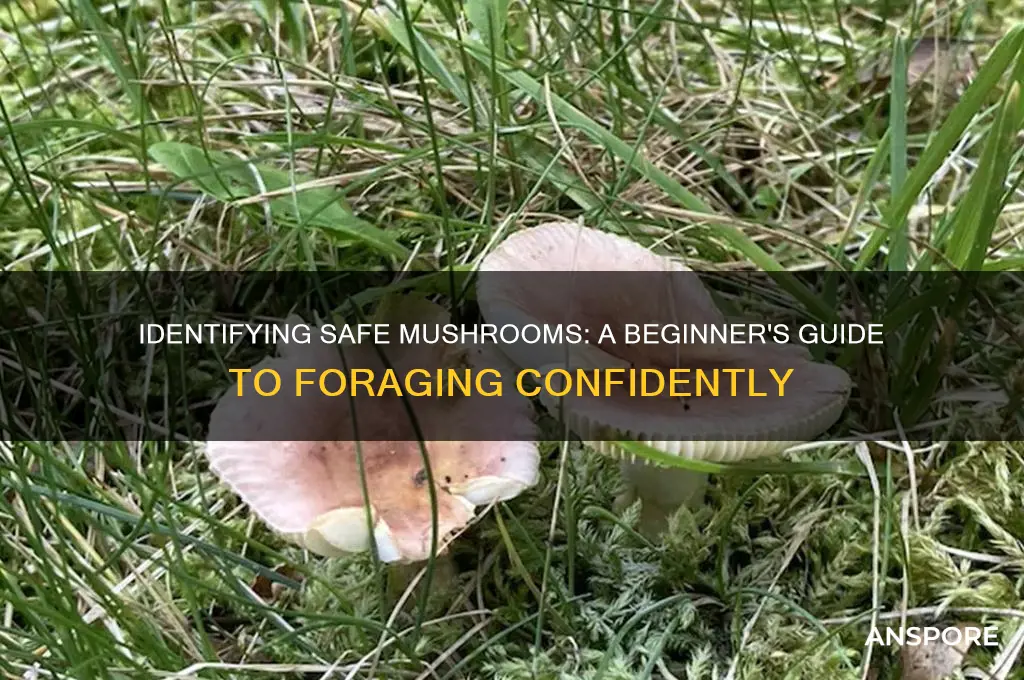

Determining whether mushrooms are safe to pick requires careful observation and knowledge, as many species closely resemble each other, with some being edible and others toxic or even deadly. Key factors to consider include the mushroom’s physical characteristics, such as its cap shape, color, gills, stem structure, and presence of a ring or volva. Additionally, noting the mushroom’s habitat, season, and associated plant life can provide crucial clues. While field guides and apps can be helpful, they should not replace expertise, as misidentification can have serious consequences. Foraging with an experienced guide or consulting a mycologist is highly recommended to ensure safety. When in doubt, the rule of thumb is to avoid consuming any wild mushroom unless its edibility is absolutely certain.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Color and Shape: Bright colors, unique shapes may indicate toxicity; research common safe species

- Gill and Stem: Check for spore color, stem bruising, and presence of a ring or veil

- Habitat Clues: Avoid mushrooms near polluted areas or certain trees; location matters for safety

- Smell and Taste: Some toxic mushrooms have strong odors; never taste to test safety

- Expert Verification: Always consult a mycologist or use reliable field guides for confirmation

Color and Shape: Bright colors, unique shapes may indicate toxicity; research common safe species

Bright colors and unusual shapes in mushrooms often serve as nature’s warning signs, a phenomenon known as aposematism. This evolutionary strategy deters predators by advertising toxicity through vivid hues like red, yellow, or green, and bizarre forms such as coral-like branches or umbrella-shaped caps with striking patterns. While not all colorful or oddly shaped mushrooms are poisonous, this correlation is strong enough to warrant caution. For instance, the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), with its iconic red cap and white dots, is both hallucinogenic and potentially harmful, illustrating how nature’s aesthetics can double as danger signals.

To navigate this visual minefield, start by familiarizing yourself with safe species in your region. Common edible mushrooms like the Button Mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) or the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) typically lack extreme colors or shapes, favoring earthy tones and familiar forms. Field guides, local mycological clubs, and apps like iNaturalist can help you identify these species accurately. Cross-reference multiple sources to confirm identifications, as misidentification can have serious consequences. Remember, even experts occasionally err, so when in doubt, leave it out.

While color and shape are useful indicators, they are not foolproof. Some toxic mushrooms, like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), mimic benign species with their plain white appearance. Conversely, edible mushrooms such as the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) have unique, shaggy spines. This underscores the importance of considering multiple characteristics, such as spore color, gill structure, and habitat, in conjunction with visual cues. Relying solely on color or shape can lead to dangerous oversimplification.

For beginners, adopt a conservative approach: avoid mushrooms with bright colors, unusual shapes, or those growing near known toxic species. Focus on learning 2–3 common, easily identifiable edible species first, such as the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which has a distinctive fan-like shape and grows on wood. Practice makes perfect—join foraging groups or workshops to gain hands-on experience under guidance. Over time, you’ll develop a nuanced understanding of when to trust visual cues and when to seek additional verification.

In conclusion, while bright colors and unique shapes often signal toxicity, they are not definitive markers. Researching and recognizing common safe species, coupled with a multi-faceted identification approach, is essential. Treat foraging as a skill to be honed gradually, prioritizing safety over curiosity. After all, the forest’s beauty lies not just in its bounty but in its mysteries—some of which are best left untouched.

Can You Eat Baby Bella Mushrooms Raw? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Gill and Stem: Check for spore color, stem bruising, and presence of a ring or veil

Spore color, often overlooked by novice foragers, is a critical indicator of a mushroom’s identity. To examine this, place the cap of a mature mushroom gill-side down on a white piece of paper for several hours. The spores released will create a distinct pattern, ranging from white and cream to pink, brown, black, or even green. For example, the deadly Amanita species often drop white spores, while the edible Agaricus (button mushrooms) leave a dark brown print. Cross-reference this color with field guides or apps like iNaturalist to narrow down the species. A mismatch between expected and observed spore color can signal a misidentification, warranting caution.

Stem bruising is another subtle yet revealing trait. Some mushrooms, like the edible Oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus), show no color change when their stems are gently squeezed. In contrast, the toxic Cortinarius species often bruise yellow or brown within minutes. To test, apply light pressure to the stem base and observe for 10–15 minutes. If discoloration occurs, avoid consumption. However, bruising alone isn’t definitive; always combine this observation with other characteristics. For instance, the edible Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus) bruises black but is safe, highlighting the need for holistic assessment.

The presence or absence of a ring or veil on the stem can dramatically shift a mushroom’s safety profile. A ring, often a remnant of the partial veil that once covered the gills, is common in Amanita species—some edible, many deadly. For instance, the "ringed" Amanita muscaria (Fly Agaric) is psychoactive and toxic, while the edible Amanita caesarea (Caesar’s Mushroom) also bears a ring. Conversely, the lack of a ring in mushrooms like Chanterelles (Cantharellus spp.) or Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus) often correlates with edibility. Always verify this feature alongside other identifiers, as rings can occasionally appear in non-Amanita species due to developmental quirks.

In practice, combining these three checks—spore color, stem bruising, and ring/veil presence—creates a robust triage system. For example, a mushroom with white spores, a bruising stem, and a ring strongly suggests an Amanita, warranting extreme caution. Conversely, brown spores, no bruising, and no ring might align with an edible Bolete. However, never rely solely on these traits; consult multiple sources and, when in doubt, discard the specimen. Foraging safely requires patience, practice, and a willingness to learn from both successes and near-misses.

Mushrooms' Role in Extracting Salts from Soil: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Habitat Clues: Avoid mushrooms near polluted areas or certain trees; location matters for safety

Mushrooms absorb their surroundings, making their habitat a critical safety indicator. Polluted areas, such as roadsides, industrial zones, or agricultural fields treated with pesticides, can concentrate toxins in fungi. For instance, a study found that mushrooms near busy highways contained elevated levels of heavy metals like lead and cadmium, which are harmful even in small doses (0.01–0.1 mg/kg body weight). If you’re foraging, maintain a buffer zone of at least 100 meters from roads or industrial sites to minimize risk.

Certain trees also signal caution. While mycorrhizal relationships between mushrooms and trees are common, some species growing near conifers like yew or certain oaks may be toxic. For example, mushrooms near yew trees can absorb taxine alkaloids, a potent cardiac toxin. Similarly, fungi near walnut trees may accumulate juglone, a compound that, while not lethal, can cause gastrointestinal distress. Cross-reference the tree species in the area with known toxic mushroom-tree pairings before harvesting.

Location isn’t just about avoiding danger—it’s also about recognizing safe zones. Mushrooms in pristine forests, away from human activity, are generally safer. Look for areas with diverse plant life, as this often indicates healthy soil and lower contamination risk. Foraging in protected parks or nature reserves can reduce exposure to pollutants, but always check local regulations to ensure harvesting is permitted.

Practical tip: Carry a portable soil test kit to check for contaminants like lead or pesticides if you’re unsure about an area. Additionally, document the habitat details (tree species, proximity to roads, etc.) when identifying mushrooms. This information can help you or experts assess safety later. Remember, even if a mushroom looks edible, its environment can render it unsafe—location is non-negotiable in foraging.

Drying vs. Pressing Mushrooms: Which Method Preserves Best?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Smell and Taste: Some toxic mushrooms have strong odors; never taste to test safety

The sense of smell can be a double-edged sword in the world of mushroom foraging. While some toxic mushrooms emit strong, unpleasant odors—like the acrid smell of bleach from the Destroying Angel or the pungent, garlicky aroma of the False Morel—others are nearly odorless, offering no olfactory clues to their danger. This variability underscores the importance of relying on multiple identification methods rather than smell alone. For instance, the Death Cap, one of the most poisonous mushrooms, has a faint, honey-like scent that might deceive even experienced foragers. Always cross-reference smell with other characteristics like spore color, gill attachment, and habitat.

A pervasive myth in mushroom foraging is the idea that tasting a small piece of a mushroom can determine its safety. This is categorically false and extremely dangerous. Toxic mushrooms like the Autumn Skullcap contain amatoxins, which can cause severe liver damage even in minute quantities. Ingesting as little as 50 grams of a toxic mushroom can be fatal for an adult, and symptoms may not appear for 6–24 hours, delaying critical treatment. Children are at even greater risk due to their lower body weight, making it essential to keep all wild mushrooms out of their reach. The bottom line: never taste a mushroom to test its safety.

If you encounter a mushroom with a strong, unusual odor, proceed with extreme caution. While not all foul-smelling mushrooms are toxic, the presence of a distinct smell should prompt further investigation. Use a field guide or mushroom identification app to compare the specimen’s other features, such as cap shape, stem structure, and spore print. For example, the stinky but edible Stinkhorn has a slimy, spore-covered tip and a distinctive phallic shape, making it easily identifiable once you know what to look for. Always err on the side of caution and leave uncertain specimens behind.

To safely incorporate smell into your foraging practice, focus on learning the odors of both toxic and edible species. Attend guided mushroom walks or join mycological societies to gain hands-on experience under expert supervision. Keep a field journal to record observations, including smells, and compare them over time. Remember, smell is just one piece of the puzzle—combine it with careful examination of physical traits and habitat to make informed decisions. By respecting the limitations of smell and taste as identification tools, you can enjoy the thrill of mushroom foraging without risking your health.

Reusing Lidia's Marinated Mushroom Liquid: Creative Kitchen Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Expert Verification: Always consult a mycologist or use reliable field guides for confirmation

Mushroom identification is a complex art, and even experienced foragers can make mistakes. While field guides and online resources offer valuable insights, they often lack the nuance to distinguish between similar species. This is where expert verification becomes crucial. Consulting a mycologist—a scientist specializing in fungi—provides an unparalleled level of accuracy. Mycologists possess the training and tools to examine microscopic features, such as spore prints and gill structures, which are essential for precise identification. For instance, the deadly Amanita ocreata closely resembles the edible Amanita velosa, but a mycologist can differentiate them by analyzing spore color and shape, ensuring safe consumption.

Reliable field guides serve as a bridge between novice foragers and expert knowledge. Look for guides authored by mycologists or experienced mycophiles, with detailed descriptions, high-quality photographs, and information on look-alike species. David Arora’s *Mushrooms Demystified* and *All That the Rain Promises and More* are exemplary resources, offering comprehensive coverage of North American fungi. However, even the best guides have limitations. Environmental factors like humidity, soil type, and maturity can alter a mushroom’s appearance, making it deviate from textbook descriptions. In such cases, cross-referencing with multiple guides or seeking expert confirmation is essential.

The stakes of misidentification are high. Toxic mushrooms like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) or the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) can cause severe organ failure or death within 48 hours. Even non-lethal species can induce gastrointestinal distress or allergic reactions. For example, the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) contains gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a component of rocket fuel. Proper preparation can reduce toxicity, but only if the species is correctly identified. This underscores the importance of expert verification, as even seasoned foragers can be fooled by deceptive appearances.

For those without access to a mycologist, joining local mycological societies or foraging clubs can provide communal expertise. These groups often host identification sessions, workshops, and guided forays led by knowledgeable members. Additionally, smartphone apps like iNaturalist allow users to upload photos for community identification, though these should be treated as preliminary rather than definitive. Always verify app results with a mycologist or reliable guide before consuming. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms but to cultivate a deep respect for the complexity and diversity of the fungal kingdom. Expert verification is not a step to bypass but a cornerstone of responsible foraging.

Can Mushrooms Eat Mushrooms? Exploring Fungal Cannibalism and Decomposition

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identifying edible mushrooms solely by appearance can be challenging and risky. While some edible mushrooms have distinct features, many toxic species resemble them. Look for key characteristics like color, shape, gills, and stem features, but always cross-reference with reliable guides or experts.

Yes, follow these guidelines: 1) Never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% sure of its identification. 2) Use reputable field guides or consult mycologists. 3) Avoid mushrooms with white spores, as many toxic species fall into this category. 4) Be cautious of mushrooms growing near polluted areas.

No, relying on myths is dangerous. Insects and animals may eat toxic mushrooms without harm, but this doesn't make them safe for humans. Always use scientific identification methods.

If in doubt, throw it out. Do not consume any mushroom unless you are absolutely certain it is safe. Consider joining a local mycological society or consulting an expert for proper identification.