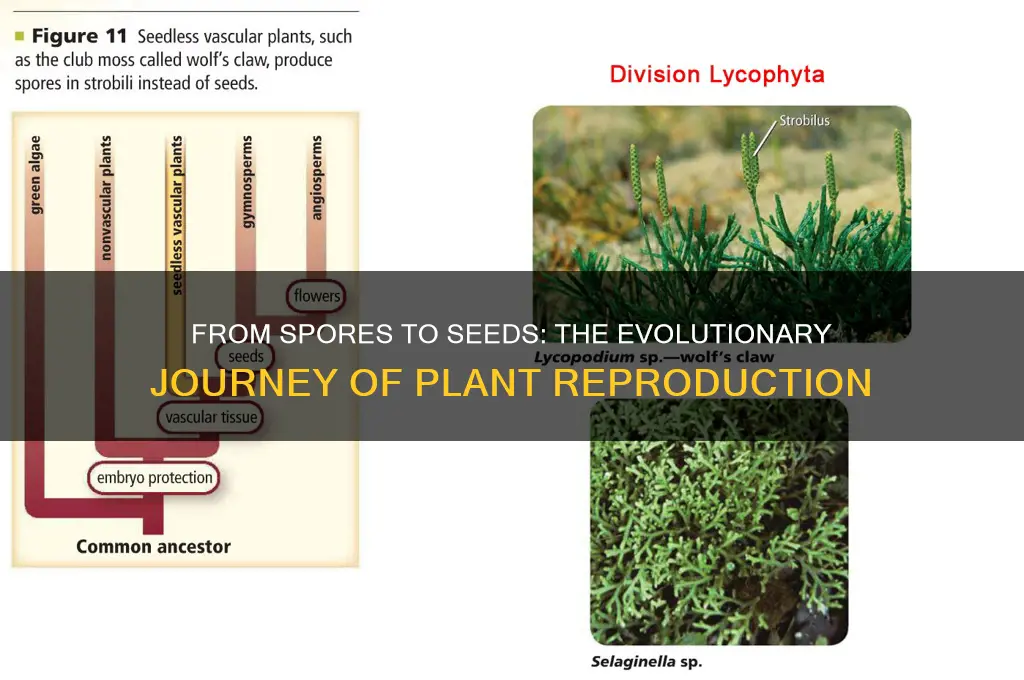

The evolution of spores to seeds marks a pivotal transition in plant history, driven by the need for greater reproductive efficiency and survival in diverse environments. Early land plants reproduced via spores, which are lightweight, single-celled structures capable of dispersing widely but highly dependent on moisture for germination. Over time, plants developed more complex structures to protect and nourish their offspring, culminating in the emergence of seeds. Seeds evolved from sporophyte tissues, incorporating a protective coat, stored nutrients, and an embryo, enabling plants to survive in drier conditions and reducing reliance on water for reproduction. This innovation not only enhanced survival but also allowed plants to colonize new habitats, ultimately leading to the dominance of seed-bearing plants in terrestrial ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Evolutionary Transition | Spores to seeds represents a major evolutionary transition in plants, marking the shift from non-seed plants (like ferns) to seed plants (like gymnosperms and angiosperms). |

| Protection | Seeds evolved to provide better protection for the embryo compared to spores. Seeds have a tough outer coat (testa) that shields the embryo from desiccation, mechanical damage, and predators. |

| Nutrient Storage | Seeds contain stored nutrients (endosperm or cotyledons) that support the embryo during germination and early growth, unlike spores which rely on immediate environmental resources. |

| Dormancy | Seeds can enter a state of dormancy, allowing them to survive unfavorable conditions (e.g., drought, cold) until optimal conditions for germination arise. Spores lack this extended dormancy capability. |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Seeds evolved specialized structures (e.g., wings, hooks, fleshy fruits) for efficient dispersal by wind, water, animals, or other agents, whereas spores rely on simpler mechanisms like wind. |

| Embryo Development | Seeds contain a well-developed embryo with a rudimentary root (radicle), shoot (plumule), and food storage tissues, whereas spores develop into a gametophyte that produces the embryo. |

| Reduced Gametophyte | In seed plants, the gametophyte (male and female) is significantly reduced in size and depends on the sporophyte for nutrition, unlike in spore-producing plants where the gametophyte is free-living. |

| Pollination | Seeds evolved in conjunction with pollination mechanisms (e.g., flowers, cones) that ensure precise delivery of male gametes to female gametes, increasing reproductive success. |

| Water Independence | Seeds can germinate in the absence of water for extended periods, whereas spores require a moist environment to germinate and grow. |

| Fossil Evidence | Fossil records show the gradual evolution of seed-like structures (e.g., pre-ovules in Devonian plants) leading to the development of true seeds in early seed plants like gymnosperms. |

| Genetic Changes | Genetic mutations and rearrangements likely played a key role in the evolution of seeds, particularly in genes controlling embryo development, nutrient storage, and dormancy. |

| Ecological Advantage | The evolution of seeds provided plants with a competitive advantage in colonizing drier and more variable environments, contributing to their dominance in terrestrial ecosystems. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Role of Pollinators: How did animal pollinators influence the transition from spore to seed reproduction

- Protection Mechanisms: What adaptations allowed seeds to protect embryos better than spores

- Water Dependency: How did seeds reduce reliance on water for reproduction compared to spores

- Nutrient Storage: Why did seeds evolve to store nutrients for seedlings, unlike spores

- Dispersal Strategies: How did seed dispersal methods evolve from spore dispersal mechanisms

Role of Pollinators: How did animal pollinators influence the transition from spore to seed reproduction?

The evolution from spore to seed reproduction marks a pivotal shift in plant history, and animal pollinators played a starring role in this transformation. Early land plants relied on spores, microscopic and wind-dispersed, for reproduction. This method, while effective in certain environments, was inherently limited by its dependence on chance and proximity. Enter animal pollinators—insects, birds, and even bats—whose interactions with plants introduced a new level of precision and efficiency. By transferring pollen directly between flowers, pollinators enabled plants to reproduce more reliably, even over greater distances. This symbiotic relationship not only benefited the animals, which gained access to nectar and pollen as food sources, but also drove the development of specialized floral structures that eventually led to the emergence of seeds.

Consider the co-evolutionary dance between plants and pollinators. As animals began visiting flowers for sustenance, plants evolved traits to attract them more effectively—bright colors, sweet scents, and nectar rewards. Over time, this mutualistic relationship favored plants that could produce larger, more nutrient-rich seeds, which in turn increased the chances of successful germination and survival. For instance, the fossil record shows that early flowering plants (angiosperms) rapidly diversified during the Cretaceous period, coinciding with the proliferation of insect pollinators. This diversification was not merely a coincidence but a direct consequence of the pollinator-driven selection pressures that favored seed-producing plants over their spore-bearing ancestors.

To understand the practical impact of pollinators, imagine a modern ecosystem without them. Many flowering plants, including staple crops like apples, almonds, and blueberries, rely on animal pollinators for reproduction. In fact, approximately 75% of global food crops depend at least partly on animal pollination. This reliance underscores the critical role pollinators played in shaping seed-based reproduction. By ensuring cross-fertilization, pollinators increased genetic diversity, making plant populations more resilient to environmental changes. Without this intervention, the transition from spores to seeds might have been slower, less efficient, or even stalled entirely.

A key takeaway is that the influence of animal pollinators extended beyond mere reproduction—it reshaped plant morphology and ecology. Flowers evolved to become more specialized, with structures like petals, stamens, and pistils designed to optimize pollinator interactions. This specialization, in turn, reinforced the dependency on pollinators, creating a feedback loop that accelerated the evolution of seed-producing plants. For gardeners or conservationists, this highlights the importance of preserving pollinator habitats. Planting native flowers, reducing pesticide use, and creating pollinator-friendly spaces can help sustain the very mechanisms that drove the spore-to-seed transition millions of years ago.

In conclusion, animal pollinators were not passive bystanders but active catalysts in the evolution from spore to seed reproduction. Their role in facilitating efficient, targeted pollination provided the selective advantage that favored seed-producing plants. By studying this relationship, we gain insights into the interconnectedness of life and the delicate balance that sustains ecosystems. Protecting pollinators today is not just an ecological imperative—it’s a tribute to their historic role in shaping the plant kingdom as we know it.

Do Moss Plants Produce Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Moss Reproduction

You may want to see also

Protection Mechanisms: What adaptations allowed seeds to protect embryos better than spores?

Seeds revolutionized plant reproduction by encapsulating embryos in protective structures, a significant upgrade from the exposed vulnerability of spores. This evolutionary leap hinged on several key adaptations that enhanced survival in diverse environments. One of the most critical advancements was the development of a seed coat, a tough outer layer derived from the ovule’s tissues. Unlike the thin, delicate walls of spores, the seed coat acts as a barrier against mechanical damage, pathogens, and desiccation. Composed of lignin, cutin, and suberin, it provides a durable shield that spores lack, ensuring the embryo remains intact even in harsh conditions.

Another pivotal adaptation is the storage of nutrients within the seed itself. While spores rely on immediate access to water and favorable conditions to germinate, seeds contain endosperm or cotyledons packed with starch, proteins, and oils. This internal food supply allows seeds to delay germination until conditions are optimal, a luxury spores cannot afford. For instance, the coconut seed can float across oceans for months, protected by its fibrous husk and nourished by its nutrient-rich endosperm, while a fern spore would perish within days without water.

Seeds also evolved dormancy mechanisms that spores lack, further enhancing protection. Dormancy ensures embryos remain viable during unfavorable periods, such as droughts or winters. This is achieved through chemical inhibitors or physical barriers within the seed coat. For example, some seeds require scarification (breaking or weakening of the seed coat) or exposure to specific temperatures before they can germinate. In contrast, spores must germinate immediately upon release, leaving them susceptible to environmental fluctuations.

Finally, seeds developed dispersal mechanisms that reduce competition and increase survival chances. Structures like wings, hooks, or fleshy fruits allow seeds to travel far from the parent plant, minimizing overcrowding and predation. Spores, while lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, lack such targeted mechanisms and often land in unsuitable or overcrowded areas. The dandelion’s feathery pappus or the burdock’s hooked seeds illustrate how seeds evolved to disperse strategically, a feature spores cannot replicate.

In summary, seeds outperformed spores in protecting embryos through the evolution of a robust seed coat, internal nutrient storage, dormancy mechanisms, and specialized dispersal strategies. These adaptations collectively ensured higher survival rates and reproductive success, marking a transformative shift in plant evolution.

Are Conidia Spores Sexual? Unraveling Fungal Reproduction Mysteries

You may want to see also

Water Dependency: How did seeds reduce reliance on water for reproduction compared to spores?

Seeds revolutionized plant reproduction by minimizing the need for water, a critical factor that limited the success of spore-based reproduction. Spores, the reproductive units of ferns and mosses, require a water film for fertilization. This dependency confines them to damp environments, restricting their geographic range and survival in arid conditions. Seeds, in contrast, evolved a protective coat and stored nutrients, enabling fertilization without external water. This adaptation allowed seed plants to colonize diverse habitats, from deserts to mountains, fundamentally altering the Earth's ecosystems.

Consider the structural innovations that facilitated this shift. Spores are lightweight, single-celled structures designed for dispersal but vulnerable to desiccation. Seeds, however, are multicellular, encased in a tough outer layer (the seed coat) that prevents water loss. Additionally, seeds contain an embryo and stored food reserves, such as starch or oils, which sustain the developing plant until it can photosynthesize. These features eliminate the need for water during fertilization and early growth, providing seeds with a survival advantage in dry environments.

To illustrate, compare the reproductive strategies of ferns and pines. Ferns release spores that must land on moist soil, where they grow into gametophytes. These gametophytes produce sperm, which swim through water to fertilize eggs, forming a new fern. In contrast, pines produce pollen grains that travel through the air to reach female cones. Fertilization occurs within the cone, and the resulting seeds remain dormant until conditions are favorable for germination. This process bypasses the need for water during fertilization, showcasing the efficiency of seed reproduction.

Practical implications of this evolution are evident in agriculture and conservation. Farmers select seed-bearing crops for their ability to withstand drought, ensuring food security in water-scarce regions. For example, sorghum and millet, both seed plants, thrive in arid climates where spore-based plants cannot survive. Conservationists also leverage this trait, using seed banks to preserve plant species threatened by climate change. By understanding how seeds reduced water dependency, we can develop strategies to protect biodiversity and sustain ecosystems in an increasingly dry world.

In conclusion, the evolution from spores to seeds represents a pivotal adaptation in plant reproduction. By eliminating the need for water during fertilization and early growth, seeds enabled plants to colonize diverse habitats, transforming the planet's landscapes. This shift underscores the importance of structural innovation in overcoming environmental constraints, offering lessons for both agriculture and conservation in the face of global challenges.

Spore's Impact on Grass Types: Debunking the Immunity Myth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nutrient Storage: Why did seeds evolve to store nutrients for seedlings, unlike spores?

Seeds, unlike spores, are equipped with a nutrient reservoir that sustains the developing seedling during its early, vulnerable stages. This evolutionary innovation addresses a critical challenge: ensuring survival in environments where resources are scarce or unpredictable. Spores, in contrast, rely on immediate access to external nutrients upon germination, leaving them susceptible to resource limitations. The seed’s nutrient storage mechanism acts as a biological insurance policy, providing a head start for the seedling before it can establish its own root system and photosynthetic capabilities.

Consider the structural differences that enable this function. Seeds contain endosperm or cotyledons, specialized tissues packed with carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. For instance, a single sunflower seed stores enough energy to support a seedling for several weeks, even in nutrient-poor soil. Spores, however, lack such storage capacity, often consisting of little more than a single cell with minimal reserves. This disparity highlights a fundamental shift in reproductive strategy: seeds prioritize long-term survival, while spores favor rapid proliferation under ideal conditions.

From an evolutionary perspective, nutrient storage in seeds emerged as a response to selective pressures in terrestrial environments. Early land plants, which reproduced via spores, faced high mortality rates due to desiccation and nutrient scarcity. Seeds evolved as a solution, encapsulating not only the embryo but also a nutrient supply to bridge the gap between germination and self-sufficiency. This adaptation allowed seed-bearing plants to colonize a wider range of habitats, from arid deserts to dense forests, outcompeting spore-dependent species in many ecosystems.

Practical implications of this evolution are evident in agriculture. Farmers exploit the nutrient reserves in seeds by optimizing germination conditions, such as maintaining soil moisture and temperature within specific ranges (e.g., 20–30°C for most crops). For example, pre-soaking seeds in water for 12–24 hours can accelerate nutrient mobilization, reducing time to emergence. Understanding this biology enables strategies like seed coating with additional nutrients or protective agents, further enhancing seedling vigor and crop yields.

In conclusion, the evolution of nutrient storage in seeds represents a pivotal adaptation that distinguishes them from spores. By internalizing resources, seeds gained a survival advantage that reshaped plant ecology and enabled diversification. This mechanism not only ensures seedling survival but also underpins modern agricultural practices, illustrating how evolutionary innovations continue to influence contemporary applications.

Cooking and Botulism: Can Heat Destroy Deadly Spores Safely?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Strategies: How did seed dispersal methods evolve from spore dispersal mechanisms?

The transition from spore to seed dispersal marks a pivotal shift in plant evolution, driven by the need for more efficient and targeted propagation strategies. Spores, being microscopic and lightweight, rely heavily on wind for dispersal, a method that is both passive and unpredictable. This randomness, while effective in certain environments, limits the ability of plants to colonize specific habitats or escape adverse conditions. Seeds, on the other hand, evolved as a more sophisticated solution, encapsulating an embryo with stored nutrients and often developing specialized structures for dispersal. This evolution was not merely a change in size or complexity but a fundamental rethinking of how plants ensure their survival and spread.

Consider the mechanisms at play: spore dispersal is inherently passive, dependent on external forces like wind currents or water flow. Seeds, however, introduced active dispersal strategies, such as the development of wings (e.g., maple seeds), hooks (e.g., burdock seeds), or fleshy fruits that attract animals. These adaptations allowed plants to target specific dispersal agents, increasing the likelihood of seeds reaching favorable environments. For instance, the evolution of fleshy fruits like berries or drupes incentivized animals to consume them, ensuring seeds were transported and deposited in nutrient-rich locations, often with a dose of natural fertilizer.

Analyzing this shift reveals a clear trend toward specialization and mutualism. While spores are a one-size-fits-all approach, seeds diversified to exploit specific ecological niches. Wind-dispersed seeds, like those of dandelions, retained the passive strategy but enhanced it with aerodynamic structures. Water-dispersed seeds, such as those of coconuts, evolved buoyant coatings to travel long distances across oceans. Animal-dispersed seeds, perhaps the most innovative, co-evolved with specific species, offering rewards like food in exchange for dispersal services. This co-evolutionary arms race highlights the dynamic interplay between plants and their environments.

Practical implications of this evolution are evident in modern agriculture and conservation. Understanding seed dispersal mechanisms helps farmers design more effective crop rotation strategies or predict the spread of invasive species. For example, knowing that burdock seeds attach to animal fur can inform measures to prevent their spread in livestock areas. Similarly, conservationists can use this knowledge to restore degraded ecosystems by planting species with dispersal traits suited to the local environment. A dosage of strategic planning, informed by evolutionary biology, can significantly enhance the success of such efforts.

In conclusion, the evolution from spore to seed dispersal represents a leap from randomness to precision. By developing specialized structures and forming symbiotic relationships, plants gained greater control over their propagation. This transformation not only ensured their survival but also shaped the diversity of ecosystems we see today. Whether through the flutter of a winged seed or the crunch of a fruit-eating animal, the legacy of this evolutionary innovation is written into every landscape.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Skin Hives? Understanding the Allergic Reaction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores evolved into seeds through a process of natural selection and adaptation. Early plants reproduced via spores, which are lightweight and easily dispersed but lack protection and nutrients. Over time, some plants developed structures that encased spores, providing protection and stored food. These structures eventually became seeds, offering advantages like better survival rates and the ability to grow in diverse environments.

Seeds provided several advantages over spores, including protection from harsh environmental conditions, stored nutrients for seedling growth, and the ability to remain dormant until favorable conditions arise. These traits allowed plants to colonize new habitats and survive in unpredictable climates, giving seed-bearing plants a competitive edge over spore-producing plants.

The first seed-bearing plants were the gymnosperms, which appeared around 360 million years ago during the Late Devonian period. These plants, including ancestors of modern conifers, produced naked seeds without protective fruit. Later, angiosperms (flowering plants) evolved around 140 million years ago, further refining seed structure with protective ovules and fruits.