Bacterial spores are highly resistant, dormant structures formed by certain bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, to survive harsh environmental conditions. Germination, the process by which spores revert to their vegetative, actively growing state, is triggered by specific environmental cues, such as nutrient availability, temperature changes, and pH shifts. During germination, the spore’s protective layers break down, allowing water and nutrients to enter, while enzymes activate metabolic processes and DNA replication resumes. This transition is tightly regulated to ensure survival and is critical for the bacteria’s life cycle, enabling them to colonize new environments and cause infections in some cases. Understanding spore germination is essential for developing strategies to control bacterial pathogens and harness beneficial bacteria in industries like food preservation and biotechnology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Trigger Mechanisms | Nutrient availability, temperature changes, pH shifts, and specific germinants like amino acids or sugars. |

| Germinant Recognition | Germinants bind to receptors in the spore's inner membrane, initiating germination. |

| Hydration | Spores absorb water, causing the spore coat to soften and swell. |

| Release of Dipicolinic Acid (DPA) | DPA, a calcium-chelated molecule, is released, reducing spore core hydration and triggering enzyme activation. |

| Enzyme Activation | Proteases and hydrolytic enzymes degrade spore-specific proteins (e.g., small acid-soluble proteins, SASPs) and peptidoglycan. |

| Core Rehydration | The spore core rehydrates, restoring metabolic activity. |

| Spore Coat Degradation | Enzymes break down the spore coat, allowing further water and nutrient influx. |

| Emergence of Vegetative Cell | The spore sheds its protective layers, and the vegetative cell resumes growth and metabolism. |

| Energy Requirements | Germination is an energy-dependent process, utilizing stored ATP and nutrients. |

| Species-Specific Variations | Germination conditions and mechanisms vary among bacterial species (e.g., Bacillus vs. Clostridium). |

| Inhibition Factors | High temperatures, extreme pH, and certain chemicals can inhibit germination. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Germination triggers: Nutrients, temperature shifts, pH changes, oxygen levels, and osmotic pressure can initiate spore germination

- Dormancy mechanisms: Spores remain dormant via thick coats, low water content, and DNA protection

- Germination stages: Activation, hydrolysis of dipicolinic acid, and cortex degradation precede outgrowth

- Enzyme roles: Germinant receptors and cortex-lytic enzymes are crucial for spore revival

- Species variations: Germination processes differ among bacterial species, e.g., *Bacillus* vs. *Clostridium*

Germination triggers: Nutrients, temperature shifts, pH changes, oxygen levels, and osmotic pressure can initiate spore germination

Bacterial spores, renowned for their resilience, remain dormant until specific environmental cues signal favorable conditions for growth. Among these triggers, nutrients stand out as a primary catalyst. Spores of *Bacillus subtilis*, for example, require specific amino acids like L-valine or L-alanine at concentrations as low as 1 mM to initiate germination. These nutrients act as chemical signals, binding to germinant receptors on the spore’s surface and triggering a cascade of events that break dormancy. Without such nutrients, spores remain inert, underscoring their role as a critical germination switch.

Temperature shifts also play a pivotal role in spore germination, particularly for species adapted to specific thermal niches. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores, which thrive in soil and food products, germinate optimally at temperatures between 30°C and 40°C. A sudden increase within this range can activate germination, while extreme temperatures may inhibit it. This sensitivity to temperature ensures spores awaken only when conditions align with their metabolic capabilities, balancing survival and growth.

PH changes act as another subtle yet powerful germination trigger. *Bacillus cereus* spores, commonly found in soil and food, exhibit increased germination rates in slightly alkaline environments (pH 8–9). Conversely, acidic conditions (pH < 5) often inhibit germination. This pH sensitivity reflects the spore’s evolutionary adaptation to specific ecological niches, ensuring germination occurs in environments conducive to bacterial proliferation.

Oxygen levels, though often overlooked, significantly influence spore germination. Anaerobic spores, such as those of *Clostridium* species, require low oxygen environments to initiate germination. Exposure to aerobic conditions can delay or prevent this process. Conversely, aerobic spores like *Bacillus* species may require oxygen to activate metabolic pathways. This oxygen dependency highlights the diverse strategies spores employ to synchronize germination with their environmental oxygen profile.

Osmotic pressure, the final trigger in this quintet, modulates spore germination by influencing water availability. Hypotonic conditions (low osmotic pressure) facilitate water uptake, swelling the spore and initiating germination. Hypertonic environments, however, can inhibit this process by limiting water access. For example, *Bacillus megaterium* spores germinate efficiently in distilled water (low osmotic pressure) but struggle in 2 M NaCl solutions (high osmotic pressure). This sensitivity ensures spores germinate only when water is abundant, a critical factor for survival in arid or saline environments.

Together, these triggers—nutrients, temperature shifts, pH changes, oxygen levels, and osmotic pressure—form a complex regulatory network that governs spore germination. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on bacterial survival strategies but also informs practical applications, from food preservation to medical treatments. By manipulating these environmental factors, we can control spore behavior, preventing unwanted germination or promoting it when beneficial.

Mastering Liquid Culture: A Step-by-Step Guide from Spore Syringe

You may want to see also

Dormancy mechanisms: Spores remain dormant via thick coats, low water content, and DNA protection

Bacterial spores are masters of survival, capable of enduring extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. Their dormancy mechanisms are a testament to evolutionary ingenuity, relying on three key strategies: thick coats, low water content, and DNA protection. These adaptations collectively create a state of suspended animation, allowing spores to persist for years, even centuries, until conditions become favorable for growth.

Consider the spore coat, a multilayered armor composed of proteins and peptidoglycan. This structure is remarkably resilient, resisting desiccation, heat, and chemical assault. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C for hours, a feat attributed to the coat’s cross-linked proteins and low permeability. This barrier not only shields the spore’s interior but also limits metabolic activity, further conserving energy. Practical applications of this durability are seen in food preservation, where spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* pose significant risks, necessitating high-temperature sterilization (121°C for 15–30 minutes) to ensure destruction.

Equally critical is the spore’s low water content, typically reduced to 20–30% of its normal level. This desiccated state halts enzymatic reactions and prevents cellular damage from ice crystal formation during freezing. Achieving such dryness involves the efflux of water and the accumulation of calcium dipicolinate, a compound that binds residual water molecules. Rehydration, a prerequisite for germination, requires access to free water, which is why spores remain dormant in dry environments. For example, spores in soil or on surfaces may persist indefinitely until rain or humidity triggers rehydration, underscoring the importance of moisture control in microbial management.

Finally, DNA protection is paramount for spore survival. The spore’s genetic material is encapsulated within a specialized structure called the core, where it is compacted and associated with small, acid-soluble proteins (SASPs). These proteins stabilize the DNA, preventing damage from UV radiation, oxidizing agents, and other stressors. Studies show that SASPs bind DNA with high affinity, reducing its susceptibility to denaturation. This mechanism ensures that upon germination, the DNA remains intact and ready for replication. Researchers have exploited this stability in biotechnology, using spores as vehicles for DNA storage and delivery in harsh environments.

In summary, bacterial spores achieve dormancy through a trifecta of defenses: a robust coat, minimal water content, and fortified DNA. Each mechanism complements the others, creating a survival strategy that is both elegant and effective. Understanding these processes not only sheds light on microbial resilience but also informs strategies for controlling spore-forming pathogens in food, medicine, and industry. Whether you’re a microbiologist, food safety specialist, or simply curious about life’s extremes, the spore’s dormancy mechanisms offer invaluable insights into the boundaries of survival.

Can Acidic Solutions Effectively Kill Botulinum Spores? Exploring the Science

You may want to see also

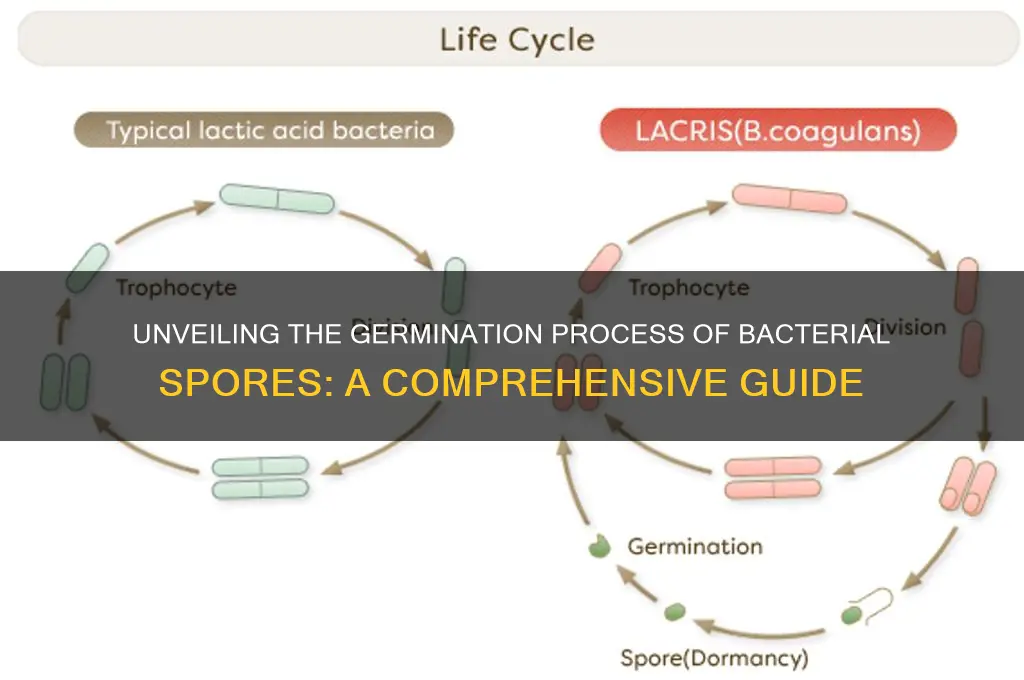

Germination stages: Activation, hydrolysis of dipicolinic acid, and cortex degradation precede outgrowth

Bacterial spores, renowned for their resilience, awaken from dormancy through a meticulously orchestrated sequence of events. The germination process, a prelude to outgrowth, unfolds in distinct stages: activation, hydrolysis of dipicolinic acid (DPA), and cortex degradation. Each step is a biochemical domino, dismantling the spore's protective barriers and priming it for revival.

Activation, the initial trigger, is a wake-up call for the dormant spore. Specific nutrients, such as amino acids (e.g., L-alanine, glycine, or L-valine), or even simple sugars like glucose, act as germinants. These molecules bind to receptors in the spore's inner membrane, initiating a signaling cascade. Think of it as a key turning in a lock, unlocking the spore's potential for life. This stage is crucial, as without the right germinant, the spore remains in its dormant state, impervious to environmental cues.

For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, the addition of 10-100 mM L-alanine effectively triggers germination. This specificity highlights the importance of understanding the preferred germinants for different bacterial species, a key consideration in both laboratory studies and real-world applications like food preservation.

The next stage, hydrolysis of DPA, is a pivotal moment in spore revival. DPA, a calcium-chelating agent, is present in high concentrations within the spore core, contributing to its heat resistance and desiccation tolerance. During germination, DPA is released through the activity of germinant receptors and associated proteins. This release lowers the core's calcium concentration, disrupting the spore's internal environment and further destabilizing its dormant state. Imagine a scaffold being dismantled, piece by piece, revealing the structure beneath.

Cortex degradation, the final preparatory step before outgrowth, involves the breakdown of the spore's outer layer, the cortex. This peptidoglycan-rich layer is hydrolyzed by specific enzymes, such as cortex-lytic enzymes (CLEs), which are activated during germination. The cortex acts as a protective barrier, and its degradation allows for the expansion of the spore and the emergence of the vegetative cell. This stage is akin to removing a protective shell, exposing the fragile contents within, ready to grow and thrive.

Understanding these germination stages is not merely academic; it has practical implications. In food preservation, for example, controlling the availability of germinants can prevent spore germination and subsequent spoilage. Conversely, in biotechnology, inducing spore germination under controlled conditions is essential for spore-based products, such as probiotics or biocontrol agents. By manipulating these stages, we can harness the power of bacterial spores, either to inhibit their growth or to promote their beneficial applications.

In summary, the germination of bacterial spores is a complex, multi-step process, where activation, DPA hydrolysis, and cortex degradation set the stage for outgrowth. Each stage is a critical checkpoint, ensuring that the spore only revives under favorable conditions. This knowledge is a double-edged sword, offering both strategies to combat spore-forming pathogens and tools to exploit their unique properties for various industries. Whether in the lab or in the field, understanding these germination stages is key to controlling the fate of bacterial spores.

Effective Methods to Remove Mold Spores from Plastic Surfaces

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Enzyme roles: Germinant receptors and cortex-lytic enzymes are crucial for spore revival

Bacterial spores, renowned for their resilience, remain dormant until specific environmental cues trigger germination. Central to this process are germinant receptors and cortex-lytic enzymes, which act as the molecular gatekeepers and executioners of spore revival. Germinant receptors, embedded in the spore’s inner membrane, detect nutrient signals such as amino acids, sugars, or purine nucleosides. Once activated, these receptors initiate a cascade of events leading to the release of dipicolinic acid (DPA) and the breakdown of the spore’s protective cortex layer. This initial step is critical, as it marks the transition from dormancy to metabolic reawakening. Without functional germinant receptors, spores remain trapped in their dormant state, impervious to even the most favorable conditions.

The role of cortex-lytic enzymes becomes pivotal once germinant receptors are activated. These enzymes, stored within the spore core, are mobilized to degrade the cortex’s peptidoglycan layer, a rigid structure that encases the spore. The cortex acts as a barrier to prevent premature rehydration and protects the core from environmental stresses. Cortex-lytic enzymes, such as CwlJ in *Bacillus subtilis*, hydrolyze the cortex’s cross-linked peptides, allowing water to penetrate and rehydrate the core. This process is tightly regulated to ensure that cortex degradation occurs only after DPA release, as premature cortex lysis would lead to spore death. The precise timing and coordination of these enzymes are essential for successful germination.

A comparative analysis of spore-forming bacteria reveals the diversity and specificity of these enzyme systems. For instance, *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species utilize distinct germinant receptors and cortex-lytic enzymes tailored to their ecological niches. In *Bacillus anthracis*, the GerH receptor responds to L-alanine, while *Clostridium perfringens* spores require a combination of L-asparagine and KCl for germination. This specificity ensures that spores revive only in environments conducive to their survival and proliferation. Understanding these differences has practical implications, such as designing targeted inhibitors to prevent germination of pathogenic spores in clinical or food safety contexts.

From a practical standpoint, manipulating these enzyme systems offers opportunities for both biotechnology and antimicrobial strategies. For example, in the food industry, controlling spore germination is crucial for preventing spoilage and foodborne illnesses. By identifying and targeting germinant receptors or cortex-lytic enzymes, researchers can develop preservatives that block germination without harming non-spore-forming bacteria. Conversely, in biotechnology, inducing spore germination under controlled conditions can enhance the production of enzymes or metabolites from spore-forming organisms. For instance, optimizing germination conditions for *Bacillus amyloliquefaciens* spores can improve their use in biofertilizers, where rapid revival is essential for soil colonization.

In conclusion, germinant receptors and cortex-lytic enzymes are not merely components of spore germination but its linchpins. Their roles highlight the intricate balance between dormancy and revival, ensuring that spores awaken only when conditions are optimal. By studying these enzymes, scientists can unlock new strategies for managing spore-forming bacteria, whether by preventing their germination in unwanted contexts or harnessing their potential in beneficial applications. This knowledge bridges the gap between fundamental biology and practical solutions, underscoring the importance of enzyme specificity in microbial survival and control.

Does Sterilization Kill Spores? Unraveling the Science Behind Effective Disinfection

You may want to see also

Species variations: Germination processes differ among bacterial species, e.g., *Bacillus* vs. *Clostridium*

Bacterial spores are renowned for their resilience, capable of surviving extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. However, their germination processes are not uniform across species. For instance, *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, two prominent spore-forming genera, exhibit distinct mechanisms and requirements for transitioning from dormant spores to active vegetative cells. Understanding these differences is crucial for applications in biotechnology, food safety, and medicine.

Consider the germination of *Bacillus* spores, which typically requires specific nutrients and environmental cues. For *Bacillus subtilis*, a model organism in spore research, germination is triggered by the presence of L-valine, a branched-chain amino acid, often in combination with purine nucleosides like inosine or guanosine. The process is rapid, with spores activating within minutes under optimal conditions. In contrast, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, germinates in response to a different set of stimuli, including elevated temperature and specific sugars, reflecting its adaptation to its mammalian host environment. These variations highlight the genus’s adaptability to diverse ecological niches.

Clostridium spores, on the other hand, often require more specific and sometimes extreme conditions to germinate. For example, Clostridium botulinum, responsible for botulism, germinates in response to certain amino acids and reducing agents, such as cysteine, which mimic the anaerobic conditions of its natural habitat. Clostridium difficile, a major cause of hospital-acquired infections, germinates in the presence of bile salts and other gastrointestinal compounds, a mechanism tied to its role in gut colonization. Unlike Bacillus, Clostridium spores often exhibit a slower germination process, which may be linked to their need to ensure favorable conditions before committing to vegetative growth.

These species-specific differences have practical implications. In food preservation, for instance, understanding the germination triggers of *Clostridium botulinum* is critical for preventing botulism in canned foods, where even trace amounts of oxygen can inhibit spore outgrowth. Similarly, in medical settings, knowing that *Clostridium difficile* spores require bile salts for germination informs strategies to control infections, such as using spore-targeting antibiotics or probiotics that modulate gut conditions. For *Bacillus* species, the rapid germination process necessitates stringent sterilization protocols in pharmaceutical manufacturing to ensure product safety.

In summary, the germination processes of bacterial spores are finely tuned to the ecological and physiological needs of each species. While *Bacillus* spores often respond quickly to general nutrients, *Clostridium* spores demand more specific and sometimes harsher conditions. Recognizing these variations not only advances our fundamental understanding of microbial life but also informs practical strategies to harness or control these organisms in various industries. Whether optimizing spore-based biotechnologies or mitigating foodborne illnesses, species-specific knowledge is indispensable.

Exploring Fungal Spores in Activated Sludge: Presence and Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bacterial spores germinate in response to specific environmental cues, such as the presence of nutrients (e.g., amino acids, purine nucleosides), warm temperatures, and appropriate pH levels. These signals indicate favorable conditions for growth and trigger the spore to exit dormancy.

Germination typically involves three stages: (1) activation, where the spore absorbs water and nutrients; (2) germination proper, where the spore releases dipicolinic acid (DPA) and breaks dormancy; and (3) outgrowth, where the spore resumes metabolic activity and grows into a vegetative cell.

Bacterial spores are highly resistant to harsh conditions, but germination requires specific favorable conditions. Without the necessary triggers like nutrients, warmth, and suitable pH, spores remain dormant and do not germinate.

Understanding spore germination is crucial for controlling bacterial infections, food preservation, and biotechnology. It helps in developing strategies to prevent spore-forming pathogens from causing disease and ensures effective sterilization processes in industries like healthcare and food production.

![SOLIGT [Thick Plastic] 3-Set Strong Seed Starter Trays with 5" Humidity Domes for Seed Starting, Germination, Seedling Propagation & Plant Growing, Holds 144 Cells in Total](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71sM72jx2IL._AC_UL320_.jpg)