Basidia, the specialized club-shaped structures found in the fruiting bodies of basidiomycete fungi, play a crucial role in spore production. Each basidium typically bears four spores, known as basidiospores, which develop at the tips of slender projections called sterigmata. The process begins with the formation of a binucleate basidium, where two haploid nuclei fuse to form a transient diploid nucleus. This nucleus undergoes meiosis, resulting in four haploid nuclei that migrate into the developing basidiospores. As the spores mature, they accumulate nutrients and thicken their cell walls, preparing for dispersal. Once fully developed, the basidiospores are released through a combination of mechanical force, such as the snapping of the sterigmata, and environmental factors like air currents or water, ensuring the continuation of the fungal life cycle.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Structure | Basidia are club-shaped cells found in the hymenium of basidiomycetes. |

| Location | Present on the gills, tubes, or pores of mushrooms. |

| Function | Produce and release spores for reproduction. |

| Nuclear Composition | Each basidium typically contains a haploid nucleus after karyogamy. |

| Spores Produced | Typically 4 spores per basidium (rarely 2 or more). |

| Spore Attachment | Spores attach to basidium via sterigmata (slender projections). |

| Meiosis | Nuclear division occurs within the basidium to form haploid nuclei. |

| Spore Maturation | Spores mature and detach from the basidium upon reaching full size. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are released into the air for wind dispersal. |

| Significance | Essential for the sexual reproduction of basidiomycetes. |

| Examples | Found in mushrooms, puffballs, and bracket fungi. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Basidium Structure: Club-shaped organ with sterigmata producing spores externally via karyogamy and meiosis

- Karyogamy Process: Fusion of haploid nuclei within basidium initiates spore development

- Meiosis in Basidia: Nuclear division forms four haploid nuclei for spore formation

- Sterigmata Role: Projections on basidium support and release individual spores efficiently

- Spore Maturation: Spores develop cell walls, become viable, and detach for dispersal

Basidium Structure: Club-shaped organ with sterigmata producing spores externally via karyogamy and meiosis

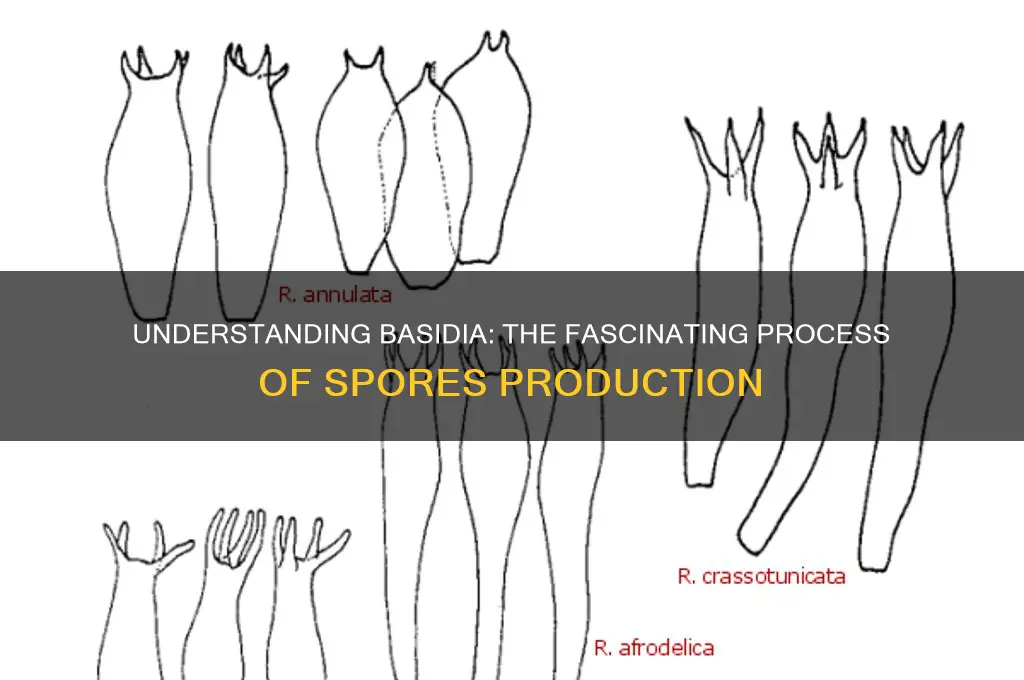

The basidium, a microscopic club-shaped organ, is the spore-producing factory of basidiomycete fungi. Imagine a tiny, elongated structure, often forked or branched, with slender projections called sterigmata radiating from its surface. These sterigmata are the birthplaces of spores, each cradling a single spore until it’s ready to be released. This external spore production is a defining feature of basidiomycetes, setting them apart from other fungal groups like the asci of ascomycetes. The process begins with karyogamy, the fusion of haploid nuclei within the basidium, followed by meiosis, which restores haploidy in the spores. This dual-step mechanism ensures genetic diversity while maintaining the life cycle’s balance between haploid and diploid phases.

To visualize the basidium’s role, consider the lifecycle of a mushroom. After a spore germinates, it grows into a haploid mycelium. When two compatible mycelia meet, they fuse, forming a diploid structure. This diploid phase is short-lived; the basidium develops as a terminal cell on the fruiting body, where karyogamy occurs. Meiosis then produces four haploid nuclei, each migrating to a sterigma to form a spore. This external spore formation is efficient, allowing spores to disperse easily via wind, water, or animals. For example, in *Coprinus comatus* (the shaggy mane mushroom), basidia are densely packed on gills, maximizing spore production and dispersal.

Understanding the basidium’s structure is crucial for practical applications, such as mushroom cultivation or fungal taxonomy. Cultivators can optimize conditions for basidium development by maintaining humidity levels around 85–95% and temperatures between 20–25°C, ideal for karyogamy and meiosis. In taxonomy, the shape, size, and arrangement of basidia and sterigmata are diagnostic features. For instance, rust fungi (*Pucciniales*) have elongated basidia with multiple sterigmata, while smut fungi (*Ustilaginomycetes*) often have swollen basidia. Observing these structures under a 40x–100x microscope can reveal species-specific traits, aiding in identification.

A comparative analysis highlights the basidium’s evolutionary advantage. Unlike asci, which enclose spores internally, basidia expose spores externally, reducing energy expenditure on spore release mechanisms. This design aligns with the ecological roles of basidiomycetes, many of which are decomposers or mycorrhizal partners, requiring efficient spore dispersal to colonize new substrates. However, this external production also makes spores vulnerable to environmental stressors like desiccation or predation. Fungi mitigate this risk through strategies like producing spores in protected locations (e.g., within gills or pores) or releasing them in humid conditions.

In conclusion, the basidium’s club-shaped structure and sterigmata exemplify nature’s ingenuity in balancing efficiency and vulnerability. By externalizing spore production, basidiomycetes maximize dispersal potential while relying on meiosis to ensure genetic diversity. Whether you’re a mycologist, cultivator, or enthusiast, understanding this structure unlocks insights into fungal biology and practical applications. Next time you examine a mushroom, take a moment to appreciate the basidia—tiny yet mighty organs driving the lifecycle of some of Earth’s most ecologically vital organisms.

Gram-Positive Rods: Exploring Spore-Negative Variants and Their Significance

You may want to see also

Karyogamy Process: Fusion of haploid nuclei within basidium initiates spore development

The karyogamy process is a pivotal moment in the life cycle of basidiomycetes, marking the fusion of two haploid nuclei within the basidium. This union is not merely a biological event but the catalyst that initiates the development of spores, ensuring the continuation of the species. Unlike mitosis, which involves the division of a single nucleus, karyogamy is a merging process, resulting in a diploid nucleus. This diploid state is transient, as it soon undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei, each destined to become a spore. Understanding this process is crucial for mycologists and enthusiasts alike, as it underpins the reproductive strategy of mushrooms and other basidiomycetes.

To visualize the karyogamy process, imagine a basidium as a microscopic factory where genetic material is reshuffled and repackaged. The basidium typically contains two haploid nuclei, each carrying a unique set of genetic information. When conditions are favorable—often signaled by environmental cues like humidity and temperature—these nuclei migrate toward each other and fuse. This fusion is highly regulated, ensuring that the genetic material combines correctly. The resulting diploid nucleus is short-lived, quickly undergoing meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei. These nuclei then migrate into emerging spore cells, known as basidiospores, which will eventually be released to colonize new environments.

From a practical standpoint, the karyogamy process has implications for mushroom cultivation and conservation. For cultivators, understanding the timing and conditions that trigger karyogamy can optimize spore production. For instance, maintaining a consistent humidity level of 85-95% and a temperature range of 20-25°C (68-77°F) during the fruiting stage can enhance the likelihood of successful nuclear fusion. Conservationists, on the other hand, can use this knowledge to protect endangered fungal species by replicating optimal conditions in controlled environments. For example, creating microhabitats that mimic natural forest floors can encourage karyogamy and spore development in rare basidiomycetes.

Comparatively, the karyogamy process in basidiomycetes contrasts with the reproductive mechanisms of other fungi, such as ascomycetes, which produce spores through asci. While both groups undergo nuclear fusion, the structural and temporal differences highlight the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies. Basidiomycetes’ reliance on a club-shaped basidium for spore production is unique, offering a distinct advantage in dispersing spores over long distances. This comparison underscores the evolutionary sophistication of the karyogamy process, which has allowed basidiomycetes to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from forest floors to decaying wood.

In conclusion, the karyogamy process is a fascinating and essential step in the spore production of basidiomycetes. By fusing haploid nuclei within the basidium, this process ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, key factors in the success of mushrooms and related fungi. Whether you’re a cultivator aiming to maximize yield or a conservationist working to protect fungal biodiversity, understanding karyogamy provides valuable insights into the intricate world of fungal reproduction. By appreciating the nuances of this process, we can better harness its potential and safeguard its role in ecosystems worldwide.

Micrococcus luteus: Understanding Its Spore Formation Capabilities Explained

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Basidia: Nuclear division forms four haploid nuclei for spore formation

Basidia, the microscopic, club-shaped structures found in fungi like mushrooms, are the factories where spores are born. At the heart of this process lies meiosis, a specialized form of nuclear division that ensures genetic diversity. Unlike mitosis, which produces identical daughter cells, meiosis in basidia results in four haploid nuclei, each carrying half the genetic material of the parent cell. This reduction in chromosome number is crucial for sexual reproduction in fungi, allowing for the formation of genetically unique spores.

Consider the steps involved in this intricate process. It begins with a diploid basidium, which undergoes meiosis I, a division that separates homologous chromosomes. This results in two haploid nuclei. Subsequently, meiosis II divides each of these nuclei into two, yielding a total of four haploid nuclei. These nuclei migrate to the tips of the basidium, where they develop into spores. Each spore, now genetically distinct, is poised for dispersal, ready to germinate under favorable conditions and start a new fungal colony.

A key takeaway from this process is its efficiency in promoting genetic diversity. By shuffling genetic material through meiosis, basidia ensure that each spore has a unique combination of traits. This diversity is vital for fungi to adapt to changing environments, resist diseases, and colonize new habitats. For instance, in agricultural settings, understanding this mechanism can inform strategies for managing fungal pathogens, as genetically diverse populations are more resilient and harder to control with a single fungicide.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend beyond agriculture. In biotechnology, the study of meiosis in basidia can inspire innovations in genetic engineering, particularly in creating diverse microbial strains for bioproducts like enzymes or biofuels. For hobbyists and educators, observing basidia under a microscope provides a tangible way to teach genetics and fungal biology. A simple experiment involves collecting mushroom caps, staining the basidia with cotton blue, and observing the four spores under 400x magnification—a vivid demonstration of meiosis in action.

In conclusion, meiosis in basidia is a masterclass in precision and purpose. By forming four haploid nuclei, it not only ensures the production of spores but also drives genetic variation, a cornerstone of fungal survival and evolution. Whether you’re a researcher, farmer, or enthusiast, grasping this process unlocks deeper insights into the fascinating world of fungi and their reproductive strategies.

Overriding Spore's Complexity Meter: Possibilities and Limitations Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sterigmata Role: Projections on basidium support and release individual spores efficiently

Basidia, the spore-producing structures in fungi, rely on sterigmata—tiny, finger-like projections—to ensure efficient spore release. These sterigmata act as specialized supports, each cradling a single spore until it’s ready for dispersal. Their role is critical: without them, spores would cluster or fail to detach, hindering reproduction. Imagine a launching pad for microscopic projectiles, and you’ll grasp their function. This precision ensures that each spore has the best chance to travel and colonize new environments, a survival strategy honed over millennia.

To understand sterigmata’s efficiency, consider their structure. Each basidium typically bears four sterigmata, one for each spore. These projections are not merely passive holders; they are dynamic structures that respond to environmental cues. As the spore matures, the sterigma elongates and curves slightly, positioning the spore for optimal release. This mechanical support is akin to a spring-loaded mechanism, ready to eject its cargo at the right moment. For instance, in the genus *Coprinus*, sterigmata aid in the rapid dispersal of spores, contributing to the fungus’s ability to decompose organic matter swiftly.

The process of spore release is a delicate balance of timing and force. Sterigmata ensure that spores are released individually, preventing clumping that could reduce dispersal range. This is particularly vital in wind-dispersed fungi, where lightweight, separated spores travel farther. A practical analogy is a seed disperser releasing seeds one by one rather than in a clump, maximizing coverage. For hobbyist mycologists, observing this under a microscope reveals the elegance of fungal engineering—each sterigma a testament to nature’s precision.

While sterigmata are universally present in basidiomycetes, their effectiveness varies by species. Some fungi, like *Amanita*, have longer sterigmata, enhancing spore propulsion. Others, such as *Pucciniomycetes*, have shorter ones, suited to their parasitic lifestyles. This diversity underscores the adaptability of sterigmata to different ecological niches. For those cultivating fungi, understanding these variations can optimize spore collection techniques. For example, gently tapping a mature basidiocarp over a sterile surface mimics natural release, aided by the sterigmata’s design.

In conclusion, sterigmata are not just structural appendages but key players in fungal reproduction. Their role in supporting and releasing spores efficiently is a marvel of biological engineering. By studying them, we gain insights into fungal survival strategies and practical applications, from spore collection to ecological restoration. Next time you encounter a mushroom, remember the unseen sterigmata—tiny yet mighty architects of fungal success.

Milky Spore's Effectiveness: Does It Kill All Beetle Grubs?

You may want to see also

Spore Maturation: Spores develop cell walls, become viable, and detach for dispersal

Spores, the microscopic units of fungal reproduction, undergo a transformative journey on the basidia—the spore-bearing cells of basidiomycetes. The maturation process is a delicate dance of cellular development, culminating in the release of viable spores ready for dispersal. This critical phase ensures the fungus’s survival and propagation, making it a fascinating subject of study for mycologists and ecologists alike.

Cell Wall Formation: The Foundation of Resilience

As spores mature on the basidium, they begin to synthesize robust cell walls, primarily composed of chitin and glucans. This structural development is essential for protecting the spore from environmental stressors such as desiccation, UV radiation, and predation. The thickness and composition of the cell wall vary among species, with some fungi producing spores capable of surviving extreme conditions, such as those found in arid deserts or polar regions. For instance, *Coprinus comatus* (the shaggy mane mushroom) develops spores with particularly resilient walls, enabling them to endure harsh weather conditions during dispersal.

Viability: The Hallmark of a Mature Spore

A spore’s viability is determined by its ability to germinate under favorable conditions. During maturation, the basidium supplies nutrients and metabolic signals that trigger the accumulation of energy reserves, such as lipids and glycogen, within the spore. This internal preparation ensures the spore can sustain itself until it lands in a suitable environment. Researchers often assess spore viability using tetrazolium chloride staining, which highlights metabolically active spores. A study on *Agaricus bisporus* (the common button mushroom) found that spores achieve peak viability within 24–48 hours of maturation, emphasizing the importance of timing in spore collection for cultivation.

Detachment and Dispersal: A Precise Mechanism

Once mature, spores must detach from the basidium to begin their journey. This process is facilitated by the formation of a small droplet of fluid, known as Buller’s drop, at the point of attachment. As the droplet evaporates, surface tension forces pull the spore away from the basidium, propelling it into the air. Wind, water, and animals then act as dispersal agents, carrying spores to new habitats. For example, *Puccinia graminis* (the stem rust fungus) relies on wind dispersal to infect wheat fields, underscoring the ecological and agricultural significance of this mechanism.

Practical Tips for Observing Spore Maturation

For enthusiasts and researchers, observing spore maturation can be both educational and rewarding. To study this process, collect a mature basidiocarp (mushroom) and place it gill-side down on a glass slide overnight. The spores will drop onto the slide, allowing you to examine their morphology and maturation stages under a microscope. For optimal results, maintain a humidity level of 80–90% and a temperature of 20–25°C during collection. Additionally, staining techniques like cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue can enhance visibility, revealing intricate details of spore structure and maturation.

In summary, spore maturation on basidia is a complex yet finely tuned process that ensures fungal survival and propagation. From cell wall formation to detachment, each step is critical for producing viable spores capable of colonizing new environments. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also has practical applications in agriculture, conservation, and biotechnology.

Can C. Botulinum Spores Harm You? Understanding the Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Basidia are specialized, club-shaped structures found in the fruiting bodies of basidiomycete fungi. They serve as the primary site for spore production, typically producing four spores externally.

Basidia produce spores through a process called meiosis, where genetic material is divided to form haploid nuclei. These nuclei migrate into protruding structures called sterigmata, where they develop into mature spores.

A basidium typically has a swollen base and a narrow stalk. At the top, four sterigmata extend outward, each bearing a single spore. The basidium’s structure ensures spores are released efficiently.

Spores are released through a process called ballistospore discharge. When mature, the spores actively detach from the sterigmata and are propelled into the air, aided by a drop in surface tension at the spore-sterigma junction.

Spore production in basidia is influenced by humidity, temperature, and light. Optimal conditions, such as high humidity and moderate temperatures, enhance spore development and release. Light can also trigger fruiting body formation in some species.