Ferns reproduce through spores, which are tiny, single-celled reproductive units produced in structures called sporangia on the undersides of their fronds. Unlike seeds in flowering plants, fern spores require moisture to germinate and develop into a small, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. This prothallus is a gametophyte, the sexual stage of the fern's life cycle, which produces both sperm and eggs. When water is present, the sperm swim to fertilize the egg, resulting in the growth of a new fern plant, known as the sporophyte. This alternating life cycle, switching between gametophyte and sporophyte generations, is a unique and fascinating aspect of fern reproduction.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

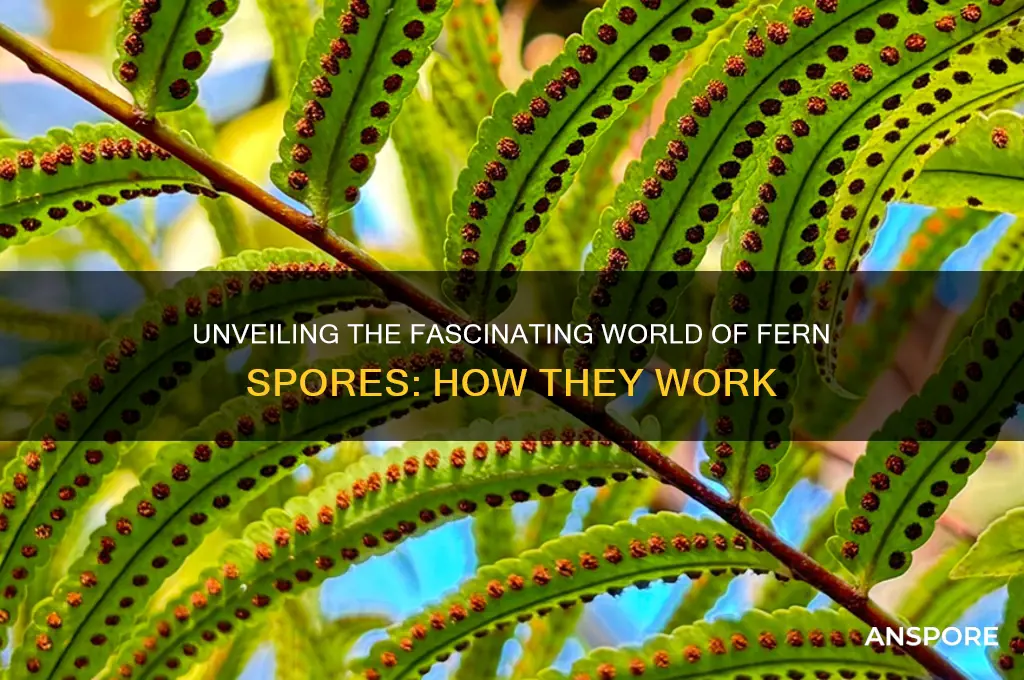

| Spores Production | Ferns produce spores in structures called sporangia, typically located on the undersides of fertile fronds (leaves). |

| Sporangia Location | Sporangia are often clustered into groups called sori, which may be protected by a membrane-like structure called the indusium. |

| Spore Type | Ferns are heterosporous, producing two types of spores: microspores (male) and megaspores (female). |

| Germination | Spores germinate into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte (prothallus) when conditions are favorable (moisture and warmth). |

| Gametophyte Function | The gametophyte is the sexual stage, producing male (sperm) and female (egg) reproductive cells. |

| Fertilization | Sperm swim to the egg using water, a process called fertilization, resulting in the formation of a zygote. |

| Sporophyte Development | The zygote develops into a new fern (sporophyte), which grows from the gametophyte and becomes the dominant stage of the fern's life cycle. |

| Life Cycle | Ferns exhibit an alternation of generations, cycling between a diploid sporophyte and a haploid gametophyte stage. |

| Dispersal | Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing ferns to colonize new areas. |

| Adaptations | Fern spores have thick walls for protection and can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions. |

| Environmental Requirements | Spores require moisture for germination and early gametophyte development, making ferns prevalent in humid environments. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Structure: Fern spores have a tough outer wall for protection and survival in harsh conditions

- Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading spores over long distances efficiently

- Germination Process: Spores require moisture and light to activate and begin growing into gametophytes

- Life Cycle Role: Spores develop into gametophytes, which produce eggs and sperm for reproduction

- Environmental Needs: Optimal conditions include humidity, shade, and nutrient-rich soil for spore success

Spore Structure: Fern spores have a tough outer wall for protection and survival in harsh conditions

Fern spores are marvels of nature, engineered for resilience. Their outer wall, composed primarily of sporopollenin, is a biochemical fortress. This tough, impermeable layer shields the delicate genetic material inside from desiccation, UV radiation, and microbial invaders. Unlike the fragile seeds of flowering plants, fern spores can endure extreme temperatures, drought, and even the vacuum of space, as demonstrated in experiments exposing them to extraterrestrial conditions. This durability ensures that spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for the ideal moment to germinate.

Consider the spore’s structure as a survival capsule. The outer wall’s thickness varies among fern species, with some, like those of the *Polypodiaceae* family, exhibiting particularly robust layers. This variation correlates with habitat—species in arid or exposed environments often have thicker walls. For instance, *Cheilanthes* ferns, adapted to rocky, dry habitats, produce spores with walls up to 3 micrometers thick, twice that of their forest-dwelling counterparts. This adaptation highlights how spore structure directly reflects evolutionary pressures.

To understand the spore’s protective mechanism, imagine a tiny, self-sustaining vault. The outer wall not only blocks physical damage but also regulates water exchange, preventing rapid dehydration while allowing minimal moisture absorption when conditions improve. This balance is critical for survival in unpredictable environments. For gardeners cultivating ferns from spores, this means they can be stored in dry, cool conditions (ideally 4–10°C) for up to 5 years without losing viability, a tip often overlooked in amateur horticulture.

Comparatively, the spore’s design outshines that of many other plant reproductive units. While angiosperm seeds rely on fleshy coatings or hard shells for protection, fern spores achieve similar resilience with a single, lightweight layer. This efficiency allows them to be dispersed over vast distances by wind, water, or animals, a strategy that has enabled ferns to colonize diverse ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to Arctic tundras. The spore’s structure, therefore, is not just a defense mechanism but a key to its ecological success.

In practical terms, understanding spore structure can enhance fern propagation efforts. For instance, scarification—a technique where the outer wall is mechanically weakened—can improve germination rates in horticulture. However, this must be done carefully, as excessive damage can render spores inviable. A recommended method is to gently rub spores on fine-grit sandpaper before sowing, mimicking natural abrasion they might experience in the wild. This simple step can increase germination success by up to 30%, particularly for species with exceptionally tough walls.

Ultimately, the spore’s outer wall is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. Its structure is a delicate balance of protection and adaptability, ensuring ferns’ survival across millennia. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or simply a nature enthusiast, appreciating this microscopic marvel offers insights into both the resilience of life and the strategies we can emulate in conservation and cultivation.

Does Traizicide Include Milky Spore? A Comprehensive Ingredient Analysis

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading spores over long distances efficiently

Ferns, ancient plants with a reproductive strategy honed over millions of years, rely on spores for survival and propagation. Unlike seeds, spores are microscopic, lightweight, and produced in vast quantities, making them ideal for dispersal over long distances. This efficiency is crucial for ferns, which often inhabit diverse and fragmented environments. Wind, water, and animals emerge as the primary agents facilitating this dispersal, each playing a unique role in ensuring the species' continuity.

Wind, the most common dispersal method, capitalizes on the spores' minuscule size and lightweight nature. Ferns typically release spores from structures called sporangia, often located on the undersides of fronds. When mature, these sporangia dry out and burst open, releasing spores into the air. Wind currents, even gentle breezes, can carry these spores for miles, depositing them in new locations. For instance, the *Pteris vittata* fern, known for its resilience, can disperse spores up to 10 kilometers under favorable wind conditions. To maximize wind dispersal, gardeners and conservationists should plant ferns in open areas with good airflow, avoiding dense vegetation that might trap spores.

Water, though less universal than wind, is a vital dispersal agent for ferns in aquatic or riparian habitats. Spores released near water bodies can be carried downstream, colonizing new shores or riverbanks. The *Ceratopteris thalictroides*, a water fern, exemplifies this strategy, with spores that float and remain viable in water for extended periods. For those cultivating ferns near water, ensuring the spores have access to flowing or stagnant water can enhance their dispersal potential. However, water dispersal is less effective in arid regions, where wind becomes the dominant force.

Animals, often overlooked, contribute significantly to spore dispersal through a process known as zoochory. Small creatures like insects, birds, and mammals inadvertently carry spores on their bodies or fur as they move through fern habitats. For example, the *Asplenium adiantum-nigrum* fern benefits from insects that crawl over its sporangia, picking up spores and transporting them to new sites. To encourage animal-mediated dispersal, planting ferns in biodiverse areas with high animal activity can be beneficial. Additionally, creating habitats that attract small mammals and insects, such as log piles or flowering plants, can indirectly support fern propagation.

Each dispersal method—wind, water, and animals—complements the others, ensuring ferns can colonize a variety of environments. While wind offers broad reach, water provides targeted dispersal in specific ecosystems, and animals bridge gaps between fragmented habitats. Understanding these mechanisms allows gardeners, conservationists, and enthusiasts to strategically enhance fern propagation. By mimicking natural conditions and leveraging these dispersal agents, we can foster the growth and survival of these remarkable plants in diverse settings.

Eukaryotic Decomposers: Spore Reproduction and Their Vital Ecological Role

You may want to see also

Germination Process: Spores require moisture and light to activate and begin growing into gametophytes

Fern spores are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in harsh conditions until the right environmental cues trigger their germination. Among these cues, moisture and light play pivotal roles in activating the dormant spores and initiating their transformation into gametophytes. This process is not merely a passive response but a finely tuned biological mechanism that ensures the survival and propagation of the species.

The Role of Moisture: Water is the first critical factor in the germination process. When a fern spore lands in a suitable environment, it absorbs moisture, which softens the spore wall and allows metabolic activity to resume. This hydration triggers the release of enzymes that break down stored nutrients within the spore, providing the energy needed for growth. Without adequate moisture, spores remain dormant, unable to initiate the developmental pathway to gametophytes. For optimal germination, a thin, consistent layer of moisture is ideal; waterlogged conditions can suffocate the spore, while overly dry environments halt the process entirely.

Light as a Catalyst: While moisture kickstarts the process, light acts as a secondary signal that guides the direction and efficiency of germination. Fern spores are often sensitive to specific light wavelengths, particularly in the blue and red spectrum, which influence their growth patterns. Blue light, for instance, promotes phototropism, encouraging the gametophyte to orient itself favorably for photosynthesis. Red light, on the other hand, can enhance cell division and overall development. In nature, this light sensitivity ensures that spores germinate in locations with sufficient illumination to support the subsequent stages of the fern's life cycle.

Practical Tips for Cultivating Fern Spores: For those attempting to grow ferns from spores, replicating these conditions is key. Start by sowing spores on a sterile, moisture-retentive medium like a mix of peat and perlite. Mist the surface lightly to maintain humidity, and cover the container with a clear lid to trap moisture without causing waterlogging. Place the setup in a well-lit area, avoiding direct sunlight, which can overheat the spores. Fluorescent grow lights with a balanced spectrum can be used to provide consistent illumination. Monitor the medium regularly, ensuring it remains damp but not saturated. With patience and attention to these details, you can observe the fascinating transition from spore to gametophyte, a testament to the intricate biology of ferns.

Comparative Insight: Unlike seeds, which often contain a fully developed embryo, fern spores are unicellular and require external conditions to initiate growth. This reliance on moisture and light highlights the fern's adaptation to environments where water and light availability are unpredictable. By contrast, seed-bearing plants have evolved internal resources that allow germination under a broader range of conditions. This comparison underscores the unique vulnerability and ingenuity of fern spores, which have thrived for millions of years by leveraging specific environmental cues to ensure their survival.

Does Lion's Mane Extract Contain Spores? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Role: Spores develop into gametophytes, which produce eggs and sperm for reproduction

Fern spores are the tiny, dust-like particles that serve as the starting point for a fern's life cycle. These spores are not seeds; they are single-celled and lack the stored nutrients found in seeds. When a spore lands in a suitable environment—typically moist and shaded—it germinates and develops into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure often no larger than a fingernail. This gametophyte is the sexual phase of the fern's life cycle, responsible for producing both eggs and sperm. Unlike the fern plant you might recognize, the gametophyte is short-lived and relies on water for sperm to swim to the egg, a process that underscores the fern's ancient, water-dependent reproductive strategy.

To understand the gametophyte's role, imagine a miniature factory designed for one purpose: reproduction. The gametophyte produces eggs in archegonia, small flask-like structures, and sperm in antheridia, which are released onto its surface. For fertilization to occur, water is essential—sperm must swim from the antheridia to the archegonia, a journey that highlights the fern's reliance on moist conditions. Once an egg is fertilized, it develops into a new fern plant, known as the sporophyte. This sporophyte will eventually produce spores, completing the cycle. The gametophyte, having fulfilled its role, withers away, its existence fleeting yet crucial.

From a practical standpoint, cultivating ferns from spores requires mimicking their natural habitat. Start by sowing spores on a sterile, moist medium like peat moss or agar. Keep the environment humid and shaded, as direct sunlight can dry out the spores before they germinate. Within a few weeks, gametophytes will appear, signaling the next phase. To encourage fertilization, maintain a water film on the surface, allowing sperm to reach eggs. This process is delicate and requires patience, but it offers a unique insight into the fern's life cycle. For enthusiasts, observing gametophytes under a magnifying glass reveals their intricate structure, a hidden world often overlooked.

Comparing fern reproduction to that of flowering plants highlights its primitive yet effective design. While flowering plants rely on pollinators and seeds, ferns depend on water and spores, a system that has remained unchanged for millions of years. This simplicity is both a strength and a limitation—ferns thrive in stable, moist environments but struggle in arid conditions. For gardeners, understanding this distinction is key. Ferns are not adaptable to all climates, but in the right setting, their life cycle can be a fascinating study in resilience and precision. By focusing on the gametophyte stage, one gains a deeper appreciation for the fern's survival strategy, a testament to nature's ingenuity.

Finally, the gametophyte's role in fern reproduction is a reminder of the plant kingdom's diversity. It bridges the gap between the microscopic spore and the towering fern, showcasing a life cycle that is both fragile and robust. For educators, this stage offers a tangible lesson in botany, illustrating concepts like alternation of generations. For hobbyists, it’s a chance to engage with nature on a microscopic level, fostering a sense of wonder. Whether you’re cultivating ferns or simply observing them, the gametophyte’s fleeting existence is a vital chapter in the fern’s story, one that deserves attention and respect.

Do Spores Need Water? Unveiling the Survival Secrets of Microscopic Life

You may want to see also

Environmental Needs: Optimal conditions include humidity, shade, and nutrient-rich soil for spore success

Fern spores are remarkably resilient, but their success hinges on specific environmental conditions. Humidity, for instance, is non-negotiable. Fern spores require a moisture-rich environment to absorb water, triggering germination. In nature, this often occurs in damp, shaded areas where evaporation is minimal. For gardeners cultivating ferns, maintaining humidity levels between 60-80% is ideal. This can be achieved by misting the soil regularly or using a humidity tray filled with water and pebbles. Without sufficient moisture, spores remain dormant, unable to initiate the growth process.

Shade plays a dual role in spore success. Direct sunlight can desiccate spores, rendering them infertile, while indirect light supports the development of young fern fronds. In their natural habitats, ferns often thrive under the canopy of taller plants or on north-facing slopes where sunlight is filtered. When growing ferns from spores, place them in a location with bright, indirect light. Avoid windows with harsh midday sun, opting instead for sheer curtains or a shaded corner. This balance ensures spores receive enough light to grow without being scorched.

Nutrient-rich soil is the foundation of fern spore success. Unlike mature ferns, spores cannot immediately access nutrients through their roots, so the soil must provide essential elements from the outset. A well-draining, organic-rich medium is key. Mix equal parts peat moss, perlite, and compost to create an ideal substrate. This blend retains moisture while preventing waterlogging, which can suffocate spores. Additionally, a light application of a balanced, water-soluble fertilizer (diluted to half the recommended strength) can provide a gentle nutrient boost once spores have germinated.

The interplay of these conditions—humidity, shade, and nutrient-rich soil—creates a microcosm where fern spores can thrive. For example, in tropical rainforests, these elements coexist naturally, fostering dense fern populations. Replicating this environment in a controlled setting requires attention to detail. Use a spray bottle to maintain humidity, position plants away from direct sun, and invest in high-quality soil amendments. By understanding and meeting these environmental needs, even novice gardeners can unlock the potential of fern spores, transforming them into lush, vibrant plants.

Milky Spore: Effective Termite Control or Just a Myth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fern spores are single-celled and require moisture to germinate, whereas seeds in flowering plants are multicellular, contain stored nutrients, and can remain dormant for longer periods.

Fern spores are lightweight and dispersed by wind, water, or animals. They thrive in moist, shaded environments, where they germinate into tiny heart-shaped gametophytes to continue the life cycle.

Once a spore lands in a moist area, it grows into a gametophyte, which produces male and female reproductive cells. Fertilization occurs when sperm swims to the egg, eventually developing into a new fern plant.