Fungal spores, often likened to seeds in plants, play a crucial role in the reproductive cycle of fungi, but they are not gametes themselves. Instead, fungi typically produce gametes through specialized structures like gametangia. However, in certain fungal groups, such as the Zygomycota, spores can function in a gamete-like manner during sexual reproduction. These spores, known as zygospores, are formed when two compatible hyphae fuse, creating a thick-walled structure that contains the genetic material from both parents. This process, known as plasmogamy, is followed by karyogamy, where the nuclei merge, resulting in a diploid zygospore. Upon germination, the zygospore undergoes meiosis, producing haploid spores that disperse and initiate new fungal growth. Thus, while fungal spores are not gametes, they can serve as key intermediates in the sexual reproductive cycle, ensuring genetic diversity and survival in diverse environments.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Structure of Fungal Spores: Fungal spores are haploid, single-celled structures designed for dispersal and survival

- Role in Reproduction: Spores act as gametes, fusing during sexual reproduction to form a zygote

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals aid spore dispersal to new environments for colonization

- Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant in harsh conditions, reviving when favorable conditions return

- Types of Spores: Include ascospores, basidiospores, and conidia, each with unique functions and structures

Structure of Fungal Spores: Fungal spores are haploid, single-celled structures designed for dispersal and survival

Fungal spores are marvels of nature, engineered for resilience and dispersal. Unlike the gametes of animals and plants, which are often short-lived and fragile, fungal spores are haploid, single-celled structures built to endure harsh conditions. This design allows them to survive in diverse environments, from arid deserts to nutrient-poor soils, ensuring the fungus’s longevity and propagation. Their simplicity—a single cell encased in a protective wall—belies their complexity in function, combining durability with adaptability.

Consider the structure of fungal spores as a survival toolkit. The cell wall, typically composed of chitin, provides mechanical strength and protection against environmental stressors like UV radiation, desiccation, and predators. Inside, the haploid nucleus carries the genetic material necessary for reproduction, while stored nutrients and metabolic reserves sustain the spore during dormancy. This minimalist yet robust design enables spores to remain viable for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate and initiate a new fungal colony.

To understand their role in reproduction, compare fungal spores to plant seeds. While seeds are diploid and require fertilization, spores are haploid and can directly develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. This asexual mode of reproduction, known as sporulation, bypasses the need for a mate, making fungi highly efficient colonizers. However, many fungi also produce gametes for sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of haploid cells to create genetically diverse offspring. Here, spores act as both dispersers and potential gametes, showcasing their dual functionality.

Practical applications of this knowledge abound. For instance, in agriculture, understanding spore structure helps in developing fungicides that target the cell wall or metabolic processes. Gardeners can use this insight to control fungal pathogens by disrupting spore dispersal or germination. Conversely, in biotechnology, spores’ resilience makes them useful in producing enzymes and antibiotics under extreme conditions. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, knowing that spores require specific triggers—like moisture and temperature—to germinate can improve cultivation success rates.

In essence, the structure of fungal spores is a testament to evolutionary ingenuity. Their haploid, single-celled design balances simplicity with functionality, enabling survival, dispersal, and reproduction in challenging environments. By studying these microscopic powerhouses, we gain not only scientific insight but also practical tools for managing fungi in agriculture, medicine, and beyond. Whether as agents of decay or partners in production, fungal spores remind us of the elegance in nature’s solutions to life’s challenges.

Deadly Fungi: Uncovering the Lethal Spores That Pose a Threat

You may want to see also

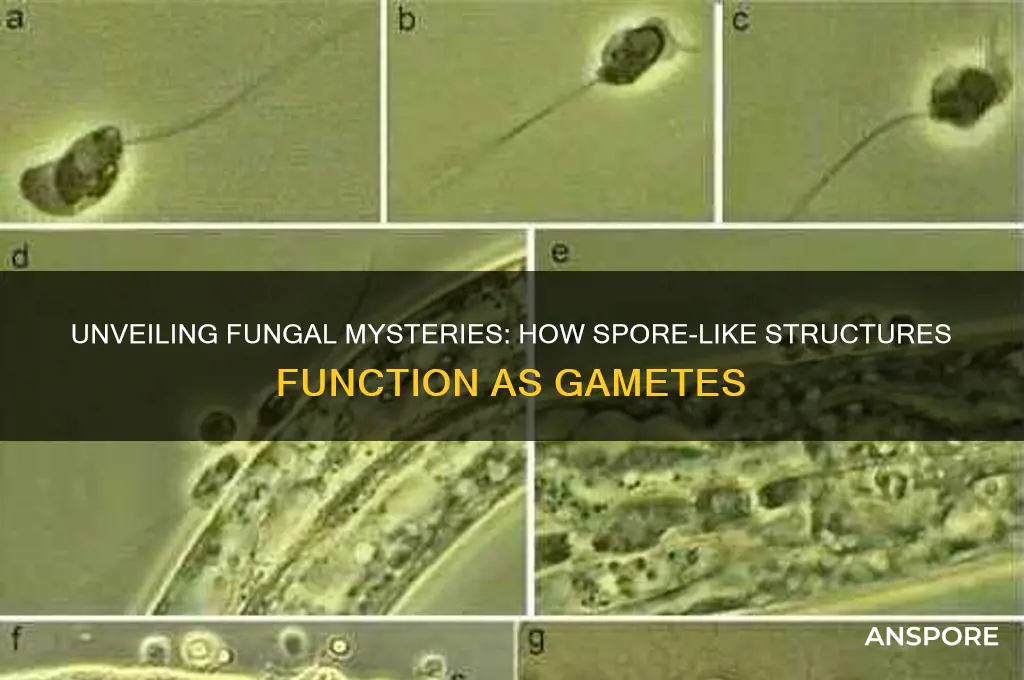

Role in Reproduction: Spores act as gametes, fusing during sexual reproduction to form a zygote

Spores in certain fungi function as gametes, playing a pivotal role in sexual reproduction by fusing to form a zygote. This process, known as karyogamy, is essential for genetic diversity and species survival. Unlike plants and animals, where gametes are distinct cells (e.g., sperm and egg), fungi often use spores as multifunctional structures that can serve both reproductive and dispersal roles. For instance, in basidiomycetes like mushrooms, haploid spores germinate into mycelia that release compatible gametes, which then fuse to create a diploid zygote. This mechanism ensures that genetic material from two individuals combines, fostering adaptability in changing environments.

Consider the life cycle of *Aspergillus*, a common mold. Here, spores act as asexual propagules but also participate in sexual reproduction when conditions favor it. When two compatible strains meet, their spores differentiate into gametangia, structures that produce gametes. These gametes fuse, forming a zygote that develops into a thick-walled zygosporangium. Over time, this structure undergoes meiosis, releasing new haploid spores capable of starting the cycle anew. This dual functionality of spores—both as dispersers and gametes—highlights their efficiency in fungal reproductive strategies.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this process is crucial for industries like agriculture and medicine. For example, controlling fungal pathogens in crops often involves disrupting spore fusion or zygote formation. Fungicides targeting these stages can prevent diseases like wheat rust or potato blight. Conversely, in biotechnology, harnessing spore fusion mechanisms can optimize the production of antibiotics or enzymes by fungi. Researchers manipulate environmental conditions to encourage sexual reproduction, thereby increasing genetic diversity and improving strain performance.

Comparatively, the role of spores as gametes contrasts with asexual reproduction, where spores clone the parent organism. Sexual reproduction via spore fusion introduces genetic recombination, a key advantage in evolving resistance to antifungals or adapting to climate change. For instance, *Cryptococcus neoformans*, a human pathogen, uses sexual reproduction to generate drug-resistant strains. By studying spore fusion, scientists can develop targeted therapies that disrupt this process, reducing the pathogen’s ability to evolve resistance.

In conclusion, spores acting as gametes are a cornerstone of fungal sexual reproduction, driving genetic diversity and species resilience. Whether in natural ecosystems or industrial applications, this mechanism underscores the adaptability of fungi. By focusing on spore fusion and zygote formation, researchers and practitioners can develop strategies to combat fungal diseases or enhance biotechnological processes. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of fungal biology but also translates into practical solutions for agriculture, medicine, and beyond.

Does Affect Spore Trigger Sleep Clause in Competitive Pokémon Battles?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals aid spore dispersal to new environments for colonization

Fungi, unlike animals or plants, rely on spores as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. These microscopic structures, often likened to seeds, are lightweight and durable, enabling them to travel vast distances. Wind, water, and animals serve as the primary agents of spore dispersal, each mechanism tailored to specific fungal species and environments. Understanding these dispersal methods is crucial for comprehending fungal ecology and managing their impact on ecosystems and human activities.

Wind Dispersal: The Aerial Voyage

Wind is perhaps the most widespread and efficient dispersal mechanism for fungal spores. Species like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* produce spores so small and lightweight that they can remain suspended in the air for hours, traveling miles before settling. This method is particularly effective for fungi in open environments, such as grasslands or forests. To maximize wind dispersal, fungi often release spores in large quantities, forming visible clouds during certain seasons. For instance, a single mushroom can release up to 16 billion spores in a day. Gardeners and farmers should note that windy conditions can exacerbate fungal infections in crops, making it essential to monitor weather patterns and apply fungicides proactively during spore release periods.

Water Dispersal: The Aquatic Journey

Water plays a vital role in dispersing spores of aquatic and semi-aquatic fungi, such as those in the genus *Chytridiomycota*. These spores are often denser than air-dispersed spores, allowing them to sink and travel through water currents. Flooding events can carry spores to new habitats, facilitating colonization of previously unoccupied areas. For example, the fungus causing chytridiomycosis in amphibians has spread globally via water systems, highlighting the ecological impact of water dispersal. Homeowners in flood-prone areas should be aware that standing water can become a breeding ground for fungal spores, potentially leading to mold growth indoors. Proper drainage and dehumidification are practical steps to mitigate this risk.

Animal-Mediated Dispersal: The Hitchhiker’s Guide

Animals, both large and small, inadvertently aid in spore dispersal by carrying them on their bodies, fur, or feathers. For instance, insects visiting mushrooms for nectar can pick up spores and transport them to new locations. Larger animals, such as deer or birds, may carry spores on their fur or feet after traversing fungal-rich areas. This mechanism is particularly effective for fungi in dense forests, where wind dispersal is limited. A notable example is the truffle fungus, which relies on animals like wild boar and squirrels to dig up and disperse its spores. Gardeners can mimic this process by introducing beneficial insects or using spore-infused substrates to enhance fungal colonization in soil.

Practical Takeaways for Effective Management

Understanding these dispersal mechanisms allows for targeted strategies to either promote or inhibit fungal growth. For instance, in agriculture, windbreaks can reduce spore transmission to crops, while controlled irrigation can minimize waterborne spore spread. In indoor environments, regular cleaning of pet areas and proper ventilation can limit animal-mediated spore dispersal. Conversely, mycorrhizal fungi, which benefit plant growth, can be intentionally dispersed using spore-infused soil amendments. By leveraging these mechanisms, individuals can manage fungal presence in their environments more effectively, whether for ecological restoration, crop protection, or mold prevention.

Touching Mold: Does It Release Spores and Pose Health Risks?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant in harsh conditions, reviving when favorable conditions return

Spores, the microscopic survival units of fungi, exhibit a remarkable ability to endure extreme conditions through dormancy. This state of suspended animation allows them to withstand desiccation, temperature extremes, and nutrient scarcity, often for years or even decades. Unlike active cells, dormant spores minimize metabolic activity, reducing their need for resources and shielding their genetic material from damage. This strategy ensures their longevity, enabling them to persist in environments where active growth would be impossible.

Consider the desert-dwelling fungus *Aspergillus niger*. Its spores can remain dormant in arid soil for extended periods, only germinating when rare rainfall provides the moisture necessary for growth. Similarly, *Neurospora crassa*, commonly known as the bread mold, produces spores that survive freezing temperatures in temperate climates, reviving when warmth and humidity return. These examples illustrate how dormancy is not merely a passive state but a finely tuned survival mechanism, triggered by environmental cues and regulated by complex biochemical pathways.

To understand the practical implications of spore dormancy, imagine a scenario where a fungal pathogen contaminates a food storage facility. Despite thorough cleaning and disinfection, spores may persist in dormant form on surfaces or in crevices. Only when conditions—such as increased humidity or nutrient availability—become favorable will these spores revive and pose a renewed threat. This underscores the importance of not only eliminating active fungal growth but also disrupting the dormant spore reservoir through methods like heat treatment or chemical agents.

From an evolutionary perspective, spore dormancy is a testament to fungi’s adaptability. By producing vast quantities of spores, fungi hedge their bets, ensuring that at least some will encounter favorable conditions in the future. This strategy is particularly effective in unpredictable environments, where resources may be scarce or conditions hostile. For instance, *Penicillium* spores can survive in the harsh conditions of outer space, as demonstrated in experiments, highlighting their robustness and potential for interplanetary dispersal.

In practical terms, understanding spore dormancy can inform strategies for fungal control in agriculture, food preservation, and medicine. For example, farmers can use crop rotation and soil solarization to disrupt the dormant spore bank of pathogens like *Fusarium*. In food processing, combining heat treatment with controlled humidity can prevent spore revival in stored products. Similarly, in healthcare, recognizing the resilience of fungal spores can guide the development of antifungal therapies that target both active cells and dormant spores, reducing the risk of recurrent infections.

Ultimately, the dormancy and survival of spores reveal a sophisticated survival strategy that has enabled fungi to thrive in virtually every ecosystem on Earth. By studying this mechanism, we gain insights into fungal biology and develop more effective methods to manage their impact, whether as beneficial organisms or harmful pathogens. This knowledge is not just academic—it has tangible applications in fields ranging from agriculture to medicine, underscoring the importance of understanding how these microscopic units persist and revive in the face of adversity.

Can Mold Spores Penetrate Your Skin? Facts and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Include ascospores, basidiospores, and conidia, each with unique functions and structures

Fungi reproduce through spores, each type uniquely adapted to its ecological niche. Among these, ascospores, basidiospores, and conidia stand out for their distinct structures and functions. Ascospores, produced within sac-like structures called asci, are the sexual spores of Ascomycetes, often referred to as "sac fungi." These spores are typically haploid and are released through a pore or slit in the ascus, dispersing to colonize new environments. For example, the ascospore of *Neurospora crassa*, a model organism in genetics, is ejected with explosive force, ensuring wide dispersal.

Basidiospores, on the other hand, are the sexual spores of Basidiomycetes, commonly known as "club fungi." These spores develop on basidia, club-shaped structures that often bear four spores at their tips. Unlike ascospores, basidiospores are externally borne, allowing for efficient wind dispersal. The mushroom *Agaricus bisporus* is a prime example, where basidiospores are released from the gills beneath the cap, each capable of germinating into a new mycelium. This external development is a key adaptation for maximizing spore dispersal in diverse habitats.

Conidia represent a different category altogether, as they are asexual spores produced by both Ascomycetes and Deuteromycetes. Unlike the sexual spores discussed earlier, conidia are formed through mitosis, making them genetically identical to the parent fungus. This asexual reproduction allows for rapid proliferation in favorable conditions. For instance, the conidia of *Aspergillus fumigatus* are ubiquitous in soil and air, and their small size (2–3 μm) enables them to penetrate deep into the respiratory system, posing health risks to immunocompromised individuals.

Comparing these spore types reveals their evolutionary strategies. Ascospores and basidiospores, being sexual spores, promote genetic diversity, which is crucial for adaptation to changing environments. Conidia, however, prioritize speed and efficiency, ensuring the fungus can quickly colonize resources. Structurally, ascospores are often thick-walled for survival in harsh conditions, basidiospores are lightweight for wind dispersal, and conidia are simple and numerous for rapid propagation.

Practical considerations arise when dealing with these spores. For instance, controlling conidia in indoor environments requires HEPA filtration to capture their small size, while managing basidiospore dispersal in mushroom cultivation involves regulating humidity and airflow. Understanding these spore types not only sheds light on fungal biology but also informs strategies for agriculture, medicine, and environmental management. Each spore type, with its unique function and structure, exemplifies the ingenuity of fungal survival mechanisms.

Buying Spores in Massachusetts: Legalities, Sources, and Cultivation Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, fungus-like spores are not gametes. Spores in fungi are typically asexual reproductive units or dispersal structures, while gametes are sex cells involved in sexual reproduction.

Fungus-like spores are usually produced through asexual means (e.g., budding, fragmentation) and serve to disperse or survive harsh conditions, whereas gametes are produced sexually (e.g., through meiosis) and fuse to form a zygote.

Yes, fungus-like organisms (e.g., fungi, slime molds) produce gametes during sexual reproduction, but these are distinct from spores. Gametes are involved in fertilization, while spores are primarily for asexual reproduction or survival.

In rare cases, some spores (e.g., zygospores in certain fungi) result from sexual fusion, but they are not gametes themselves. Gametes are the cells that fuse to form these sexual spores.