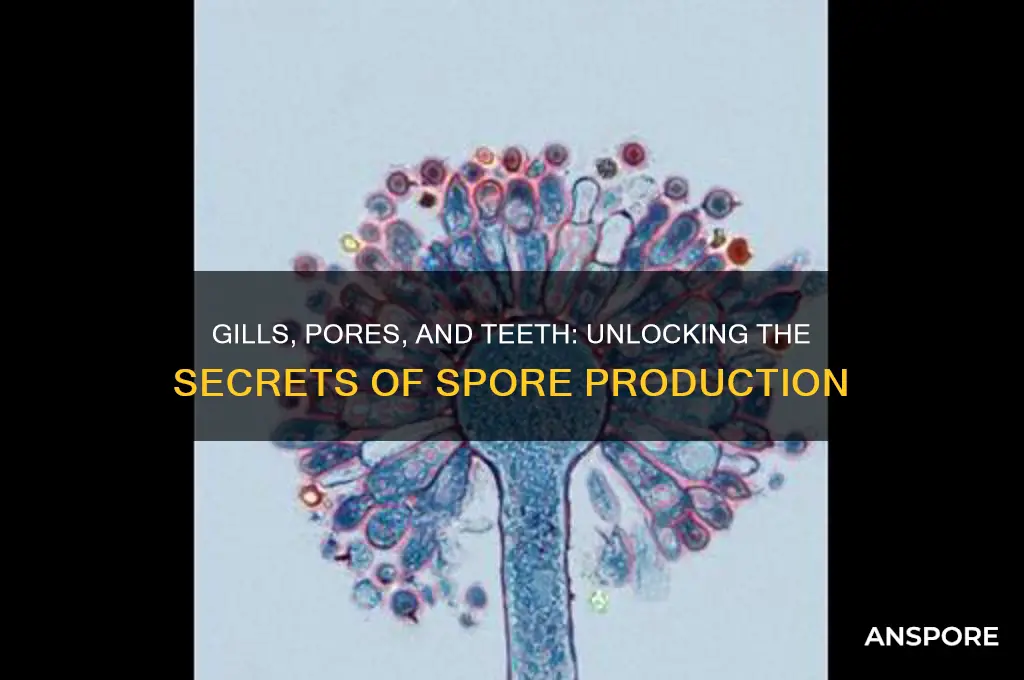

Gills, pores, and teeth play crucial roles in the life cycles of certain fungi, particularly in spore production and dispersal. Gills, found on the undersides of mushroom caps, serve as the primary site for spore formation, where basidia (spore-bearing cells) develop and release spores into the environment. Pores, characteristic of polypores and boletes, function similarly by housing spore-producing structures called basidia within their tubular openings, allowing for efficient spore release. Teeth, seen in fungi like the hydnoid species, are spine-like structures that also bear spores, increasing the surface area for spore production and dispersal. Together, these structures maximize the efficiency of spore release, ensuring the widespread propagation of fungal species through various ecological niches.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Gills | Gills in fungi (e.g., mushrooms) provide a large surface area for spore dispersal. They are thin, closely spaced structures that allow spores to be released efficiently into the air. |

| Pores | Pores (found in polypores and other fungi) act as openings through which spores are released. They regulate spore discharge and protect spores until optimal conditions for dispersal. |

| Teeth | Teeth (found in hydnoid fungi) are spine-like structures that hold spores. As the teeth dry out or are disturbed, spores are released into the environment. |

| Spore Production | Gills, pores, and teeth are specialized structures that facilitate spore production and dispersal, ensuring fungal reproduction and colonization of new habitats. |

| Efficiency | These structures maximize spore release efficiency by increasing surface area, protecting spores, and responding to environmental cues (e.g., wind, touch). |

| Adaptations | Each structure is adapted to the fungus's habitat: gills for open-cap mushrooms, pores for woody polypores, and teeth for hydnoid fungi in specific ecological niches. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Gills' role in spore dispersal mechanisms

Gills, often associated with aquatic organisms, play a surprisingly intricate role in spore dispersal mechanisms, particularly in certain fungi. Unlike their respiratory function in fish, fungal gills—technically called lamellae—serve as a structural platform for spore release. These thin, blade-like structures maximize surface area, allowing spores to be efficiently ejected into the surrounding environment. For instance, in mushrooms like the common *Agaricus bisporus*, gills are densely packed beneath the cap, each lined with basidia—spore-bearing cells. As spores mature, they are launched from the basidia, using the gills as a springboard to catch air currents, ensuring widespread dispersal.

To understand the mechanics, consider the process as a natural catapult system. When water droplets or air disturbances interact with the gills, they create vibrations that dislodge spores. This passive yet effective method relies on the gills’ architecture, which positions spores at an optimal angle for ejection. Studies show that a single mushroom can release up to 10 billion spores in a 24-hour period, a feat made possible by the gill structure. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, maintaining humidity levels between 85–95% enhances spore release, as moisture activates the basidia more effectively.

Comparatively, gills outperform other fungal structures like pores or teeth in spore dispersal efficiency. While pores, found in polypores, release spores through small openings, they lack the dynamic ejection mechanism of gills. Teeth, seen in species like *Hericium erinaceus*, rely on gravity or physical contact for spore release, limiting their range. Gills, however, combine structural design with environmental triggers, making them superior for long-distance dispersal. This adaptability is why gilled fungi dominate diverse ecosystems, from forests to urban gardens.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to mycology and conservation. For example, when cultivating gilled mushrooms, ensure proper air circulation to mimic natural dispersal conditions. Avoid overcrowding fruiting bodies, as this can hinder spore ejection. Additionally, foragers should handle mushrooms gently to preserve gill integrity, maximizing spore release in the wild. Understanding gills’ role not only deepens appreciation for fungal biology but also informs sustainable practices in agriculture and ecology. By leveraging this mechanism, we can enhance spore production for food, medicine, and ecosystem restoration.

Does B. Coagulans Produce Spores? Unveiling the Probiotic's Survival Mechanism

You may want to see also

Pore structure and spore release efficiency

The intricate design of pore structures in fungal gills plays a pivotal role in spore release efficiency, a process critical for the organism's survival and propagation. These microscopic openings, often arranged in intricate patterns, serve as gateways for spores to exit the fungal body. The size, shape, and distribution of these pores directly influence the force and direction of spore discharge, a mechanism that has evolved to maximize dispersal range and colonization potential. For instance, the common mushroom *Agaricus bisporus* exhibits pores with a diameter of approximately 10-20 micrometers, optimized for efficient spore release under varying environmental conditions.

Consider the process of spore release as a finely tuned mechanical system. When mature spores accumulate within the gill structure, they create internal pressure, which, combined with environmental triggers like humidity changes, prompts the pores to open. This release is not random; it is a highly coordinated event where the pore's architecture determines the velocity and trajectory of the spores. Studies have shown that species with elongated, narrow pores, such as those in the genus *Phallus*, achieve greater dispersal distances compared to those with wider, more circular openings. This is because the narrow pores act as nozzles, accelerating the spores with minimal energy loss.

To optimize spore release efficiency, fungi have evolved pore structures that respond dynamically to environmental cues. For example, in humid conditions, some species increase pore aperture size to facilitate easier spore exit, while in drier environments, they may reduce aperture size to conserve moisture. This adaptability is crucial for survival in diverse habitats. Researchers have found that manipulating environmental humidity levels can significantly impact spore release rates, with optimal conditions varying by species. For instance, *Coprinus comatus* releases spores most efficiently at 90-95% relative humidity, while *Schizophyllum commune* performs best at 70-80%.

Practical applications of understanding pore structure and spore release efficiency extend beyond mycology. In agriculture, this knowledge can inform the development of biofungicides, where controlled spore dispersal is essential for effective pest management. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, optimizing grow room humidity based on species-specific requirements can dramatically increase yield. For example, maintaining a humidity level of 85-90% during the fruiting stage of *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom) can enhance spore release and subsequent colonization of substrate.

In conclusion, the pore structure in fungal gills is a marvel of natural engineering, finely tuned to maximize spore release efficiency. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into fungal ecology and unlock practical applications in agriculture and cultivation. Whether you're a researcher, farmer, or enthusiast, understanding the interplay between pore architecture and environmental conditions can lead to more effective strategies for harnessing the power of fungi.

Boiling Water: Effective Method to Kill Spores or Not?

You may want to see also

Teeth function in spore attachment and spread

In the intricate world of fungi, the role of teeth in spore attachment and spread is a fascinating adaptation that ensures the survival and proliferation of species. Unlike the more commonly recognized gills and pores, which primarily facilitate spore release, teeth serve a distinct purpose in anchoring spores to surfaces, thereby enhancing their dispersal efficiency. These microscopic, tooth-like structures, found on the hymenium of certain fungi, act as hooks or barbs that catch and hold spores until optimal conditions for release are met. This mechanism is particularly crucial in environments where wind or water currents are inconsistent, ensuring that spores remain attached until they can be effectively dispersed.

Consider the *Hydnellum* genus, where teeth are prominently featured. These fungi thrive in woodland areas, and their teeth are adapted to retain spores in the damp, shaded understory. When a potential disperser, such as an insect or small mammal, brushes against the teeth, the spores are dislodged and carried away. This targeted dispersal strategy increases the likelihood of spores reaching suitable substrates for germination. For enthusiasts studying these fungi, observing the structure and density of teeth under a microscope can provide valuable insights into the species' ecological preferences and dispersal mechanisms.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the function of teeth in spore attachment can aid in fungal cultivation and conservation efforts. For instance, when cultivating tooth fungi like *Hericium erinaceus* (lion's mane mushroom), ensuring the substrate mimics their natural environment—rich in decaying wood and moisture—can enhance tooth development and, consequently, spore production. Additionally, foragers and mycologists should handle tooth fungi gently to avoid prematurely dislodging spores, which could reduce the chances of successful colonization in the wild.

Comparatively, while gills and pores rely on passive release mechanisms, teeth offer a more controlled and strategic approach to spore dispersal. This distinction highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of fungi, tailoring their structures to specific ecological niches. For example, tooth fungi often inhabit environments where passive dispersal would be less effective, such as dense forests or shaded areas with limited airflow. By contrast, gilled mushrooms like *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom) thrive in open environments where wind can easily carry spores.

In conclusion, the teeth of certain fungi play a critical role in spore attachment and spread, offering a unique solution to the challenges of dispersal in specific habitats. By studying these structures, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for fungal diversity but also practical knowledge applicable to cultivation, conservation, and ecological research. Whether you're a mycologist, forager, or simply a nature enthusiast, recognizing the function of teeth in spore production adds another layer to the fascinating world of fungi.

Can Mold Spores Enter Through Your Eyes and Ears?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gills and pores in spore maturation processes

Gills and pores play a pivotal role in the maturation of spores, particularly in fungi, by facilitating gas exchange and regulating moisture levels. In species like mushrooms, gills are the primary site of spore production, acting as a vast surface area where basidia (spore-bearing cells) develop. These gills are often densely packed to maximize exposure to air, ensuring efficient dispersal of spores. Pores, on the other hand, are found in polypores and boletes, serving a similar function by allowing gases to diffuse in and out of the fruiting body. Both structures are critical for maintaining the microclimate necessary for spore development, as spores require adequate oxygen and controlled humidity to mature properly.

Consider the lifecycle of a mushroom: as the fruiting body emerges, gills or pores begin to secrete enzymes that break down surrounding organic matter, releasing nutrients essential for spore growth. Simultaneously, the intricate network of gills or pores ensures that carbon dioxide produced during metabolism is expelled, while oxygen is absorbed. This gas exchange is vital for the energy-intensive process of sporulation. For instance, in *Agaricus bisporus* (the common button mushroom), gills must be fully exposed to air for spores to reach maturity. Without this exposure, spores remain underdeveloped and incapable of germination.

Practical observations reveal that environmental conditions significantly impact the functionality of gills and pores. High humidity, for example, can clog these structures, hindering gas exchange and leading to malformed spores. Conversely, excessively dry conditions can desiccate the fruiting body before spores are fully mature. Cultivators of edible mushrooms often maintain relative humidity levels between 85–95% and ensure proper ventilation to optimize gill and pore function. For home growers, using a humidifier and placing a fan on low speed can mimic these conditions, promoting healthy spore maturation.

Comparatively, the role of gills and pores in spore maturation highlights their evolutionary adaptation to diverse environments. Gills, with their exposed structure, are more common in fungi thriving in open, well-ventilated habitats, such as meadows. Pores, however, are often found in wood-decaying fungi, where their protected structure prevents debris from obstructing gas exchange. This distinction underscores how these features are tailored to specific ecological niches, ensuring spore production remains efficient regardless of the environment.

In conclusion, gills and pores are not merely structural components but dynamic systems integral to spore maturation. Their ability to regulate gas exchange and moisture levels directly influences the viability and dispersal of spores. By understanding their function, cultivators and researchers can optimize conditions for fungal growth, whether in controlled environments or natural settings. This knowledge not only enhances agricultural practices but also deepens our appreciation for the intricate biology of fungi.

Fixing Spore Error 1004: Default Preferences Not Found Solutions

You may want to see also

Teeth and gills interaction in spore distribution

In the intricate world of fungi, the interplay between teeth and gills is a fascinating mechanism for spore distribution. Certain fungi, like the hydnoid fungi (commonly known as "tooth fungi"), feature spines or teeth-like structures instead of gills. These teeth are not just structural anomalies; they are optimized for spore release. Unlike the broad surface area of gills, teeth provide a more focused, vertical surface where spores can accumulate and be dislodged by air currents or passing organisms. This design ensures that spores are released in a controlled, directional manner, increasing the likelihood of dispersal to new habitats.

Consider the process in action: as spores mature on the teeth, their weight or environmental factors like wind cause them to detach and fall. The spacing between teeth creates channels that guide air flow, enhancing spore ejection. For instance, in species like *Hericium erinaceus* (lion's mane mushroom), the elongated teeth act as miniature spore catapults, launching spores upward and outward. This mechanism is particularly effective in forest environments where air movement is limited, ensuring spores travel beyond the immediate vicinity of the fungus.

However, the interaction between teeth and gills in spore distribution is not limited to tooth fungi alone. Some fungi exhibit hybrid structures, combining gill-like folds with tooth-like projections. These transitional forms highlight evolutionary adaptations to diverse environments. For example, in humid climates, gills may dominate to maximize spore surface exposure, while in drier areas, teeth may prevail to conserve moisture and focus dispersal efforts. Understanding these adaptations provides insights into fungal ecology and can inform conservation strategies for spore-dependent species.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to mycology and agriculture. Cultivators of edible fungi like *Hydnellum peckii* (the "bleeding tooth fungus") can optimize spore collection by mimicking natural air flow patterns around teeth structures. Additionally, studying these mechanisms aids in identifying fungal species in the wild, as tooth and gill configurations are key taxonomic features. For hobbyists, observing these structures under a magnifying glass reveals the elegance of fungal design, turning a forest walk into a lesson in spore biology.

In conclusion, the interaction between teeth and gills in spore distribution is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. Whether through the focused ejection of spores from teeth or the broad exposure of gills, fungi have evolved diverse strategies to ensure their survival. By studying these mechanisms, we not only deepen our appreciation for fungal biology but also unlock practical applications in cultivation, conservation, and identification. Next time you encounter a tooth fungus, take a moment to marvel at its spore-dispersing prowess—it’s a tiny yet mighty feat of natural engineering.

Can Humans Safely Inhale Funaria Spores? Exploring the Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Gills in fungi, such as mushrooms, provide a large surface area for spore-producing structures (basidia) to develop. As spores mature, they are released from the gills into the air, aiding in dispersal and reproduction.

Pores, found in polypores and boletes, are openings on the underside of the fungus where spores are produced. Each pore contains spore-bearing structures (tubes) that release spores, facilitating their spread through the environment.

Teeth-like structures, seen in tooth fungi (Hydnoid fungi), contain spore-producing cells embedded in their surfaces. As spores mature, they are released from the teeth, allowing for wind or animal-mediated dispersal.

No, gills, pores, and teeth are distinct structures found in different fungal groups. Gills are common in agarics, pores in polypores and boletes, and teeth in Hydnoid fungi, each adapted to their specific spore dispersal mechanisms.