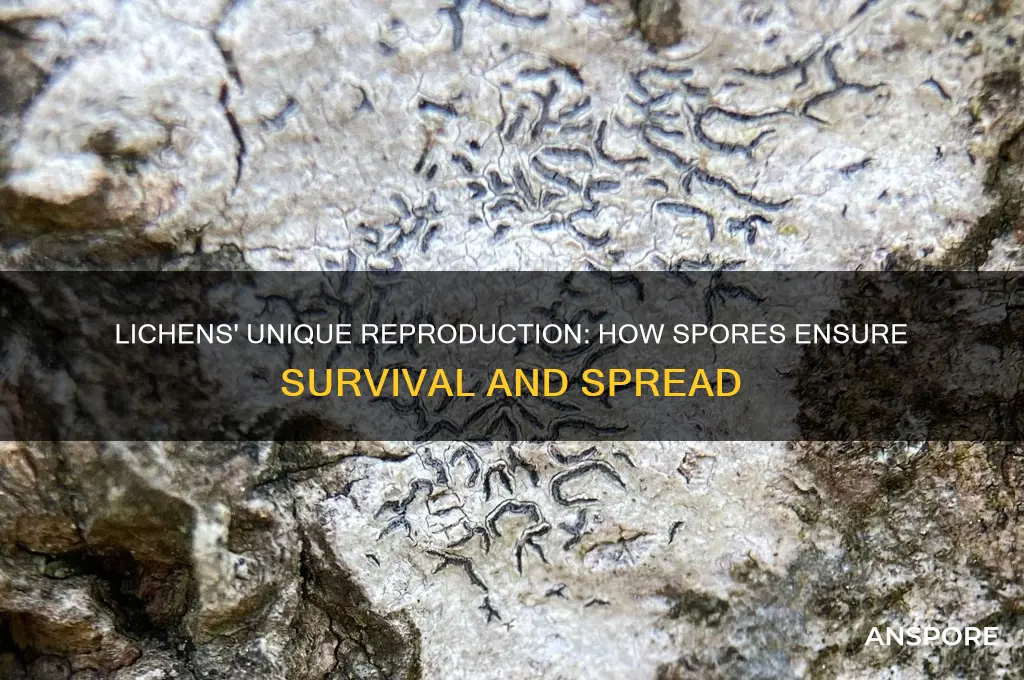

Lichens, unique symbiotic organisms composed of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria, reproduce primarily through the dispersal of spores, a process that ensures their survival and colonization of new habitats. The fungal partner, which forms the majority of the lichen’s structure, produces spores in specialized structures such as apothecia, perithecia, or pycnidia, depending on the lichen species. These spores are typically haploid and are released into the environment, where they can travel via wind, water, or animals. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates and seeks out a compatible algal or cyanobacterial partner to re-establish the lichen symbiosis. Additionally, lichens can reproduce asexually through fragmentation, where small pieces of the lichen break off and grow into new individuals, but spore reproduction remains the primary method for genetic diversity and long-distance dispersal.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Asexual and sexual reproduction via spores. |

| Asexual Reproduction | Through fragmentation, soredia, or isidia. |

| Sexual Reproduction | Involves the production of spores by the fungal partner (ascomycetes or basidiomycetes). |

| Spores Produced | Ascospores (in ascomycetes) or basidiospores (in basidiomycetes). |

| Sporocarp Structures | Apothecia (cup-like structures) or perithecia (flask-shaped structures) for spore release. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals. |

| Germination | Spores germinate upon landing in a suitable environment with a compatible algal partner. |

| Role of Photobiont | The algal or cyanobacterial partner (photobiont) is typically acquired from the environment, not via spores. |

| Environmental Requirements | Requires suitable substrate, moisture, and compatible photobiont for successful establishment. |

| Time to Mature | Newly formed lichens may take months to years to become fully established. |

| Adaptability | Lichens can colonize new habitats efficiently due to their spore dispersal and symbiotic nature. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores Production: Lichens produce spores in fruiting bodies like apothecia, perithecia, or pyrenocarps

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, or animals aid in dispersing spores to new environments

- Germination Process: Spores land on suitable substrates, germinate, and grow into new lichens

- Symbiotic Re-establishment: Fungal spores must reconnect with compatible algae or cyanobacteria to form lichens

- Asexual Reproduction: Some lichens fragment, creating soredia or isidia for vegetative reproduction

Spores Production: Lichens produce spores in fruiting bodies like apothecia, perithecia, or pyrenocarps

Lichens, those resilient organisms that thrive in some of the harshest environments on Earth, rely on specialized structures for spore production. These structures, known as fruiting bodies, are the factories where spores are created, matured, and eventually dispersed. Among the most common types are apothecia, perithecia, and pyrenocarps, each with distinct forms and functions. Apothecia resemble cup-like structures that open to the air, allowing spores to be released freely. Perithecia, on the other hand, are flask-shaped and release spores through a small opening, while pyrenocarps are embedded in the lichen’s tissue, providing a more protected environment for spore development. Understanding these structures is key to grasping how lichens propagate and survive across diverse ecosystems.

Consider the apothecium, a fruiting body that is both functional and aesthetically striking. Often found in crustose and foliose lichens, apothecia rise above the lichen’s surface, exposing their spore-bearing layer to the environment. This design maximizes spore dispersal through wind or water, ensuring that the lichen’s genetic material can travel far and wide. For instance, the lichen *Xanthoria parietina* produces bright orange apothecia that are not only visually distinctive but also highly efficient in releasing spores. To observe this process, one can collect a sample, place it under a magnifying glass, and note the cup-like structures brimming with spores. This hands-on approach offers a tangible way to appreciate the ingenuity of lichen reproduction.

In contrast, perithecia and pyrenocarps demonstrate how lichens adapt to different environmental challenges. Perithecia, commonly found in lichens like *Collema*, are more enclosed, protecting spores from desiccation and predation. This design is particularly advantageous in arid or exposed habitats where open structures like apothecia might be less effective. Pyrenocarps, often seen in lichens such as *Verrucaria*, are even more protected, being completely embedded within the lichen’s thallus. While this limits the distance spores can travel, it ensures a higher survival rate in harsh conditions. These variations highlight the evolutionary flexibility of lichens, tailoring their reproductive strategies to their specific environments.

For those interested in studying or documenting lichen reproduction, identifying these fruiting bodies is a critical skill. Start by examining the lichen under a hand lens or microscope, noting the shape, color, and position of the structures. Apothecia are typically easy to spot due to their raised, open form, while perithecia and pyrenocarps may require closer inspection. A practical tip is to use a field guide or online resource to compare your observations with known species. For example, the presence of apothecia in *Cladonia* species (commonly known as reindeer lichens) can be confirmed by their distinctive podetium, a stalk-like structure that elevates the fruiting bodies. This methodical approach not only aids in identification but also deepens one’s appreciation for the complexity of lichen biology.

Finally, the study of lichen fruiting bodies offers broader insights into ecological resilience and biodiversity. By producing spores in such varied and specialized structures, lichens ensure their survival in environments ranging from polar deserts to tropical rainforests. This adaptability makes them invaluable indicators of environmental health, as changes in lichen populations can signal shifts in climate or pollution levels. For conservationists and enthusiasts alike, understanding spore production in lichens is not just an academic exercise but a practical tool for monitoring and protecting fragile ecosystems. Whether through fieldwork, laboratory analysis, or citizen science, exploring these microscopic marvels can yield profound ecological and scientific rewards.

Archegoniophore's Role in Efficient Spore Dispersal: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, or animals aid in dispersing spores to new environments

Lichens, those resilient symbiotic organisms, rely heavily on external forces to disperse their spores and colonize new habitats. Wind, water, and animals act as unwitting couriers, each playing a unique role in this ecological journey. Wind, the most common dispersal agent, carries lightweight lichen spores over vast distances, a process known as anemochory. These spores, often produced in specialized structures like apothecia or perithecia, are designed for aerodynamic efficiency, allowing them to travel on air currents until they settle on suitable substrates. For instance, *Usnea* species, commonly known as beard lichens, produce abundant spores that can be carried kilometers away, ensuring their survival in diverse environments.

Water, though less frequently utilized, serves as a dispersal medium for lichens in specific ecosystems. Hydrophobic lichens, such as those found in coastal or riparian zones, release spores that can float on water surfaces, a mechanism termed hydrochory. This method is particularly effective in humid environments where water bodies act as natural highways. For example, *Verrucaria* species, often found on wet rocks, rely on water flow to transport their spores to new locations. While this method is less widespread than wind dispersal, it highlights the adaptability of lichens to their surroundings.

Animals, too, contribute to spore dispersal, albeit indirectly. Zoochory occurs when spores adhere to the fur, feathers, or exoskeletons of animals, hitching a ride to new areas. Lichens growing on tree bark or soil are particularly prone to this form of dispersal, as animals like birds, insects, and mammals frequently come into contact with them. For instance, ants have been observed carrying lichen fragments, inadvertently aiding in their colonization of new substrates. This method, while less predictable than wind or water, underscores the interconnectedness of lichen ecosystems with their animal counterparts.

Understanding these dispersal mechanisms is crucial for conservation efforts and ecological studies. Wind-dispersed lichens, for example, may require open landscapes to thrive, while water-dispersed species depend on the preservation of aquatic habitats. Practical tips for observing these processes include monitoring lichen-rich areas after storms to track wind dispersal or examining water bodies near lichen colonies for signs of hydrochory. By recognizing the role of external agents in spore dispersal, we gain deeper insights into the resilience and adaptability of lichens in diverse environments.

Unveiling the Truth: Are Mold Spores Toxic to Your Health?

You may want to see also

Germination Process: Spores land on suitable substrates, germinate, and grow into new lichens

Lichens, those resilient organisms that thrive in some of the harshest environments on Earth, rely on a delicate yet robust process to propagate: spore germination. When spores settle on a suitable substrate—a surface that provides the necessary moisture, nutrients, and stability—they initiate a transformation from dormant particles into thriving lichen organisms. This critical phase hinges on the substrate’s ability to retain water and offer a firm anchor, as lichens are symbiotic partnerships between fungi and algae or cyanobacteria, requiring a stable base to establish their complex structure.

The germination process begins with the spore absorbing water, triggering metabolic activity within its cell. This rehydration activates enzymes that break down stored nutrients, fueling the growth of a germ tube—a filamentous structure that emerges from the spore. The germ tube acts as a pioneer, extending outward to secure a stronger hold on the substrate. For lichens, this step is particularly crucial because the fungus component (the mycobiont) must establish a symbiotic relationship with its photosynthetic partner (the photobiont) early in development. Without successful germination, this partnership cannot form, and the lichen cannot grow.

Once the germ tube anchors the spore to the substrate, the next phase involves the development of a thallus—the body of the lichen. This growth is slow and methodical, as the fungus envelops the photobiont, creating a protective environment for photosynthesis. The substrate’s composition plays a pivotal role here; porous materials like rock or bark allow the lichen to penetrate and secure itself, while smoother surfaces may hinder this process. Practical tip: gardeners and conservationists can enhance lichen colonization by providing rough-textured materials in areas with suitable humidity and light conditions.

A cautionary note: not all substrates are created equal. Factors like pH, pollution levels, and competition from other organisms can impede germination. For instance, acidic substrates may inhibit spore viability, while high levels of air pollution can damage the delicate structures of germinating spores. To maximize success, ensure the substrate is free from contaminants and matches the lichen species’ preferred environmental conditions. For example, *Cladonia* species thrive on sandy soils, while *Usnea* prefers bark or twigs.

In conclusion, the germination of lichen spores is a finely tuned process that bridges dormancy and growth, relying on the interplay between spore, substrate, and environment. By understanding this mechanism, we can better support lichen propagation in both natural and cultivated settings. Whether you’re a researcher, gardener, or conservationist, creating optimal conditions for spore germination is key to fostering these remarkable organisms.

Do Liquid Culture Spores Expire? Shelf Life and Storage Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Symbiotic Re-establishment: Fungal spores must reconnect with compatible algae or cyanobacteria to form lichens

Lichens, those resilient organisms that cling to rocks and trees, owe their existence to a delicate dance between fungi and photosynthetic partners—algae or cyanobacteria. When a lichen reproduces using spores, it’s not just the fungus dispersing its genetic material; it’s launching a quest for symbiotic re-establishment. These fungal spores, often microscopic and wind-dispersed, must locate and reconnect with compatible algae or cyanobacteria to regenerate the lichen structure. Without this reunion, the spore remains a solitary fungus, incapable of forming the composite organism we recognize as a lichen.

Consider the process as a biological matchmaking challenge. Fungal spores, released from structures like apothecia or pycnidia, drift through the environment until they land on a suitable substrate. Here, they germinate into hyphae, the thread-like structures of fungi. However, their survival as a lichen depends on encountering a compatible algal or cyanobacterial partner. This compatibility isn’t random; it’s governed by specific biochemical and ecological factors. For instance, the fungus *Trebouxia* often pairs with green algae, while *Nostoc* cyanobacteria are common partners for cyanolichens. The success rate of this reconnection is surprisingly low, highlighting the precision required in nature’s design.

To increase the odds of symbiotic re-establishment, researchers have experimented with controlled environments. In laboratory settings, fungal spores are introduced to algal cultures in petri dishes, where nutrient-rich agar supports initial growth. A key tip for enthusiasts or scientists attempting this: maintain a pH level between 5.5 and 6.5, as this range mimics the natural conditions favorable for lichen formation. Additionally, exposing the cultures to alternating light and dark cycles (12 hours each) can simulate natural day-night rhythms, encouraging symbiosis. While this method isn’t foolproof, it offers insights into the conditions that foster successful reconnection.

Comparing natural and artificial environments reveals the challenges of symbiotic re-establishment. In the wild, spores face unpredictable factors like humidity, temperature, and competition from other microorganisms. For example, in arid regions, cyanobacteria-based lichens dominate due to their nitrogen-fixing abilities, which enhance survival in nutrient-poor soils. In contrast, algae-based lichens thrive in moister environments where light penetration is higher. This ecological specificity underscores why not all fungal spores succeed in forming lichens, even when partners are abundant.

The takeaway is clear: symbiotic re-establishment is a fragile yet fascinating process that hinges on compatibility, environment, and chance. Whether in nature or the lab, the journey from spore to lichen is a testament to the intricate relationships that sustain life. For those studying or cultivating lichens, understanding these dynamics isn’t just academic—it’s a practical guide to preserving these vital organisms in an ever-changing world.

Mold Spores and Gut Health: Uncovering the Hidden Connection

You may want to see also

Asexual Reproduction: Some lichens fragment, creating soredia or isidia for vegetative reproduction

Lichens, those resilient organisms that thrive in diverse environments, have evolved unique strategies for asexual reproduction. Among these, fragmentation stands out as a remarkably efficient method. Certain lichens break apart, forming tiny structures called soredia or isidia, which serve as miniature replicas of the parent organism. These fragments, often powdery or granular in texture, are dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing the lichen to colonize new surfaces without the need for spores.

Consider the process of creating soredia: these are powdery masses of algal cells and fungal filaments, typically found on the surface of the lichen thallus. When a fragment of soredia lands on a suitable substrate—a rock, tree bark, or even soil—it can grow into a new lichen. This method is particularly effective in stable environments where conditions are favorable for growth. For instance, *Xanthoria parietina*, a common lichen found on urban walls, frequently reproduces via soredia, enabling it to spread rapidly across available surfaces.

Isidia, on the other hand, are more structured. These are outgrowths that resemble tiny fingers or coral-like branches, protruding from the lichen’s surface. Unlike soredia, isidia are less likely to break off accidentally, but when they do, they carry with them the necessary components to develop into a new lichen. *Usnea*, a genus of beard lichens, often reproduces through isidia, which are dispersed by wind or animals brushing against them. This method is advantageous in environments where physical contact is frequent, such as in dense forests.

While both soredia and isidia are effective, they come with trade-offs. Soredia are more easily dispersed but less protected, making them vulnerable to desiccation or predation. Isidia, though more robust, are less likely to detach and travel far. For enthusiasts or researchers cultivating lichens, understanding these differences is crucial. For example, when propagating *Cladonia* species, which often produce soredia, ensure the substrate is moist and shaded to mimic their natural habitat. Conversely, when working with isidia-producing lichens like *Evernia*, focus on creating opportunities for physical dispersal, such as placing them in areas with gentle air movement.

In practical terms, observing these structures under a magnifying glass can reveal their role in reproduction. Soredia appear as fine, colored powders, while isidia look like miniature branches. For educational purposes, collecting samples from different environments and comparing their reproductive structures can provide valuable insights into lichen ecology. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a scientist, recognizing these asexual strategies highlights the ingenuity of lichens in ensuring their survival and expansion across diverse ecosystems.

Does Bleach Kill Bacterial Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind Disinfection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Lichens reproduce using spores through asexual and sexual methods. The fungal partner (mycobiont) produces spores, which are dispersed by wind or water. These spores can grow into new lichens if they land in a suitable environment and find a compatible algal or cyanobacterial partner.

Lichens produce two main types of spores: asexual spores (conidia) and sexual spores (ascospores). Conidia are produced through asexual reproduction and are typically dispersed directly from the lichen thallus. Ascospores are produced through sexual reproduction within structures called asci, found in fruiting bodies like apothecia or perithecia.

No, lichens cannot reproduce solely through spores without their symbiotic partner. The fungal spores must find and associate with a compatible algal or cyanobacterial partner to form a new lichen. Without this partnership, the spores cannot develop into a functional lichen.