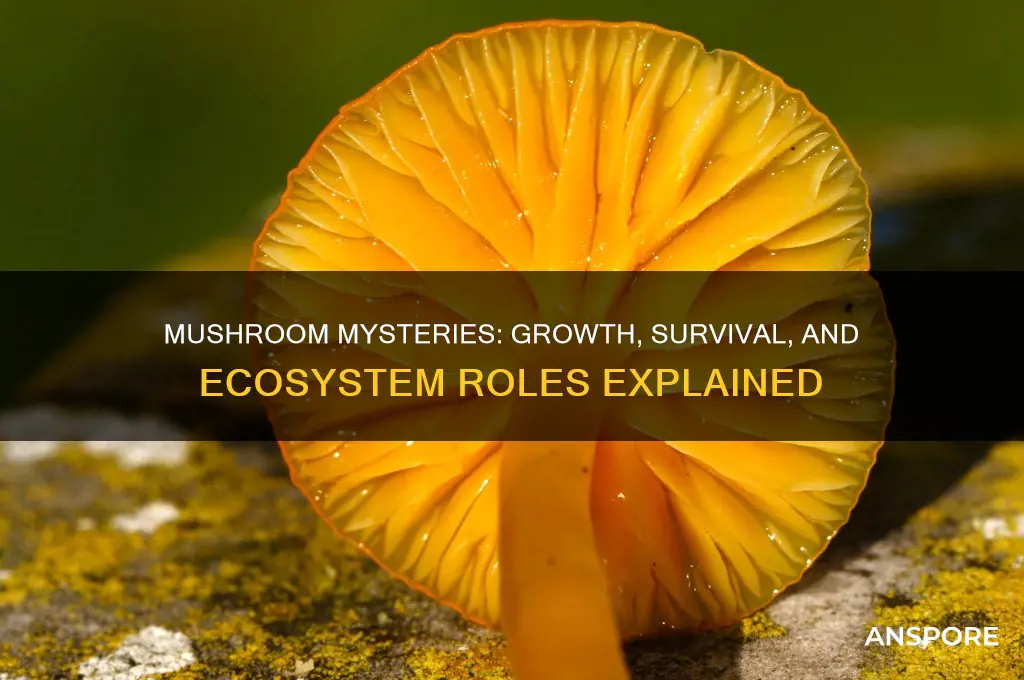

Mushrooms, often overlooked yet vital components of ecosystems, thrive through a unique and intricate life cycle. Unlike plants, they lack chlorophyll and instead obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter, such as dead wood, leaves, and soil, through a network of thread-like structures called mycelium. This mycelium acts as the mushroom's root system, secreting enzymes to break down complex materials into simpler forms that can be absorbed. Mushrooms reproduce via spores, which are dispersed through the air, water, or animals, allowing them to colonize new habitats. Their ability to recycle nutrients makes them essential decomposers, contributing to soil health and nutrient cycling in forests, grasslands, and other ecosystems. Additionally, mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with plants, enhancing their access to water and nutrients, further cementing their role as key players in ecological balance and survival.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Growth Environment | Mushrooms thrive in moist, dark, and humid environments, often in soil, decaying wood, or organic matter. |

| Nutrient Source | They are saprotrophic, obtaining nutrients by decomposing dead organic material (e.g., leaves, wood). |

| Mycelium Network | Mushrooms grow from a network of thread-like structures called mycelium, which spreads underground. |

| Spores for Reproduction | They reproduce via spores released from gills or pores under the cap, dispersed by wind, water, or animals. |

| Symbiotic Relationships | Some mushrooms form mutualistic relationships with plants (mycorrhiza), aiding nutrient exchange. |

| pH and Temperature Tolerance | Prefer slightly acidic to neutral pH (4.5–7.0) and temperatures between 55–75°F (13–24°C). |

| Decomposition Role | Play a key role in ecosystems by breaking down complex organic matter, recycling nutrients. |

| Resilience to Adversity | Can survive harsh conditions (e.g., drought) by remaining dormant as mycelium until favorable conditions return. |

| Chemical Defense Mechanisms | Produce toxins or bitter compounds to deter predators and protect themselves. |

| Seasonal Growth Patterns | Often grow in specific seasons (e.g., fall) when moisture and temperature conditions are optimal. |

| Ecosystem Contribution | Support biodiversity by providing food for animals and improving soil health through decomposition. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Dispersal Mechanisms: Mushrooms release spores through wind, water, or animals for widespread germination

- Mycorrhizal Relationships: Fungi form symbiotic partnerships with plants to exchange nutrients and enhance survival

- Decomposition Role: Mushrooms break down organic matter, recycling nutrients in ecosystems efficiently

- Environmental Adaptations: Fungi thrive in diverse habitats, tolerating extreme conditions like darkness or acidity

- Predator Defense Strategies: Mushrooms use toxins, bitter tastes, or camouflage to deter consumption by animals

Spore Dispersal Mechanisms: Mushrooms release spores through wind, water, or animals for widespread germination

Mushrooms, as fungi, have evolved sophisticated spore dispersal mechanisms to ensure their survival and proliferation in diverse ecosystems. Unlike plants that rely on seeds, mushrooms reproduce through spores, which are microscopic, lightweight, and produced in vast quantities. These spores serve as the primary means of dispersal, allowing mushrooms to colonize new habitats and thrive in various environments. The success of a mushroom species often hinges on its ability to effectively disperse spores, and nature has provided several ingenious methods to achieve this.

One of the most common and efficient spore dispersal mechanisms is through the wind. Mushrooms that utilize this method typically have gills, pores, or teeth underneath their caps, where spores are produced. When the mushroom matures, the spores are released into the air, often in response to environmental cues such as changes in humidity or temperature. The lightweight nature of spores allows them to be carried over long distances by even the gentlest breeze. This wind-driven dispersal is particularly effective in open environments like forests and grasslands, where air currents can transport spores to new locations, increasing the chances of germination and colonization.

Water also plays a crucial role in spore dispersal for certain mushroom species. Aquatic or semi-aquatic fungi release their spores into water bodies, where currents and tides carry them to new areas. Some mushrooms have adapted to this method by producing spores with hydrophobic coatings or structures that allow them to float on water surfaces. Rainfall can also dislodge spores from mushroom caps, washing them into the soil or nearby water sources. This water-based dispersal is especially important in wetland ecosystems, where mushrooms contribute to nutrient cycling and decomposition processes.

Animals, including insects and larger fauna, are another vital vector for spore dispersal. Many mushrooms have evolved attractive features, such as bright colors or enticing odors, to lure animals. As insects like flies or beetles visit the mushroom to feed or lay eggs, they inadvertently pick up spores on their bodies. When these animals move to other locations, they deposit the spores, facilitating germination in new areas. Similarly, mammals and birds may consume mushrooms or brush against them, carrying spores on their fur or feathers. This animal-mediated dispersal is highly effective in forested ecosystems, where it ensures the widespread distribution of mushroom species across different habitats.

In addition to these primary mechanisms, some mushrooms employ unique strategies to enhance spore dispersal. For instance, certain species have "active" mechanisms, such as the forceful ejection of spores from specialized structures. The puffball mushroom is a classic example, releasing clouds of spores when its mature fruiting body is disturbed. Other mushrooms rely on explosive mechanisms, where the sudden release of built-up pressure propels spores into the air. These specialized adaptations highlight the remarkable diversity and ingenuity of spore dispersal mechanisms in the fungal kingdom.

Understanding these spore dispersal mechanisms provides valuable insights into how mushrooms grow and survive in ecosystems. By harnessing the power of wind, water, and animals, mushrooms ensure their spores reach diverse environments, increasing their chances of successful germination and colonization. This widespread dispersal not only aids in the survival of individual mushroom species but also plays a critical role in maintaining ecosystem health, as fungi contribute to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships with other organisms.

Backyard Mushroom Cultivation: A Beginner’s Guide to Growing Fungi at Home

You may want to see also

Mycorrhizal Relationships: Fungi form symbiotic partnerships with plants to exchange nutrients and enhance survival

Mycorrhizal relationships are fundamental to the survival and growth of mushrooms within ecosystems, as they involve a symbiotic partnership between fungi and plants. In this relationship, fungi colonize the roots of plants, forming a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae extend far beyond the reach of the plant’s root system, significantly increasing the plant’s ability to absorb water and essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen from the soil. In exchange, the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis, which the fungus cannot synthesize on its own. This mutual exchange ensures both organisms thrive in environments where resources might otherwise be scarce.

The mycorrhizal network acts as an underground highway, facilitating the transfer of nutrients and signals between plants and fungi. This interconnected system enhances the resilience of both partners to environmental stressors such as drought, pathogens, and nutrient deficiencies. For instance, during periods of water scarcity, the extensive hyphal network can access moisture from distant areas, supplying it to the plant. Similarly, fungi can protect plants from soil-borne diseases by outcompeting harmful pathogens or by directly antagonizing them through the production of antimicrobial compounds. This protective mechanism is crucial for the survival of both the fungus and the plant in challenging conditions.

Beyond nutrient exchange and protection, mycorrhizal relationships play a vital role in soil structure and health. Fungal hyphae bind soil particles together, improving soil aggregation and reducing erosion. This enhances water retention and aeration, creating a more favorable environment for plant growth. Additionally, as fungi decompose organic matter, they release enzymes that break down complex compounds, making nutrients more accessible to plants. This process contributes to the overall fertility of the ecosystem, supporting a diverse array of plant and microbial life.

The survival of mushrooms in an ecosystem is deeply intertwined with their mycorrhizal partnerships. Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, produced when conditions are favorable for spore dispersal. The energy and nutrients acquired through the mycorrhizal relationship enable fungi to allocate resources to mushroom development. These fruiting bodies release spores that can colonize new plants, perpetuating the symbiotic cycle. Without the benefits derived from mycorrhizal associations, many fungi would struggle to survive and reproduce in nutrient-limited environments.

In summary, mycorrhizal relationships are a cornerstone of mushroom survival and growth in ecosystems. By forming symbiotic partnerships with plants, fungi gain access to essential carbohydrates while enhancing the plant’s nutrient uptake and resilience. This mutualistic interaction not only benefits the individual organisms but also contributes to the overall health and stability of the ecosystem. Understanding these relationships highlights the interconnectedness of life and the critical role fungi play in sustaining plant communities and ecosystem functions.

Outdoor Oyster Mushroom Cultivation: Simple Steps for a Bountiful Harvest

You may want to see also

Decomposition Role: Mushrooms break down organic matter, recycling nutrients in ecosystems efficiently

Mushrooms play a crucial role in ecosystems as primary decomposers, breaking down complex organic matter into simpler substances. Unlike plants, which produce their own food through photosynthesis, mushrooms lack chlorophyll and must obtain nutrients by decomposing dead or decaying material. This process begins when fungal hyphae—the thread-like structures that make up the mushroom’s body—secrete enzymes onto organic matter such as fallen leaves, wood, or dead animals. These enzymes break down cellulose, lignin, and other tough compounds that most organisms cannot digest, converting them into nutrients the fungus can absorb. This ability makes mushrooms indispensable in nutrient cycling, as they unlock resources trapped in dead organisms and return them to the ecosystem.

The decomposition process carried out by mushrooms is highly efficient and ensures that essential elements like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus are not permanently locked away in dead matter. As hyphae penetrate organic material, they fragment it into smaller pieces, increasing the surface area for enzymatic action. This fragmentation accelerates decomposition, allowing nutrients to be released more rapidly. For example, in forests, mushrooms break down fallen trees and leaf litter, preventing the accumulation of debris and maintaining soil health. Without mushrooms and other fungi, organic matter would decompose much more slowly, leading to nutrient scarcity and reduced ecosystem productivity.

Mushrooms also form symbiotic relationships with bacteria and other microorganisms during decomposition, creating a collaborative network that enhances their efficiency. These partnerships allow fungi to access additional resources and break down a wider range of materials. For instance, some bacteria help fungi degrade lignin, a complex polymer found in wood, while fungi provide bacteria with a habitat and organic compounds. This synergy ensures that even the most recalcitrant organic matter is eventually broken down, highlighting the interconnectedness of decomposers in ecosystems.

The nutrients released by mushrooms during decomposition are vital for plant growth and overall ecosystem functioning. As fungi absorb nutrients from decaying matter, they store them in their biomass. When mushrooms and other fungal structures die or are consumed by other organisms, these nutrients are released back into the environment. This recycling process replenishes the soil, supporting the growth of plants and other primary producers. In this way, mushrooms act as a bridge between dead organic matter and living organisms, sustaining the flow of energy and nutrients through the ecosystem.

Finally, the decomposition role of mushrooms contributes to long-term soil fertility and ecosystem resilience. By breaking down organic matter, fungi improve soil structure, making it more porous and capable of retaining water. This enhances the soil’s ability to support plant life and withstand environmental stresses such as drought. Additionally, the nutrients released by mushrooms promote biodiversity by providing resources for a wide range of organisms, from microorganisms to large herbivores. Thus, mushrooms are not only key players in decomposition but also foundational to the health and stability of ecosystems worldwide.

Can Mushrooms Thrive Without Soil? Exploring Alternative Growing Mediums

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Adaptations: Fungi thrive in diverse habitats, tolerating extreme conditions like darkness or acidity

Fungi, including mushrooms, exhibit remarkable environmental adaptations that enable them to thrive in diverse and often extreme habitats. One of their key survival strategies is their ability to tolerate darkness, a condition that would be detrimental to most photosynthetic organisms. Unlike plants, fungi do not rely on sunlight for energy production. Instead, they are heterotrophs, obtaining nutrients by decomposing organic matter or forming symbiotic relationships with other organisms. This allows them to flourish in dark environments such as deep forest floors, caves, and underground ecosystems. Their capacity to break down complex organic materials in the absence of light ensures their survival in niches where competition for resources is minimal.

Another critical adaptation of fungi is their tolerance to acidic environments. Many fungal species can thrive in soils with low pH levels, which are inhospitable to most other life forms. This is due to their robust cell walls, composed primarily of chitin, which provides structural integrity and protection against harsh conditions. Additionally, fungi produce enzymes that can function optimally in acidic conditions, enabling them to decompose organic matter efficiently. This adaptability makes them essential decomposers in ecosystems like peatlands and coniferous forests, where acidity is high.

Fungi also demonstrate remarkable resilience in extreme temperature conditions. Some species can survive in freezing environments, such as the Arctic or high-altitude regions, by producing antifreeze proteins that prevent ice crystal formation in their cells. Conversely, thermophilic fungi thrive in hot environments like geothermal areas, where temperatures can exceed 50°C. These fungi have enzymes and cellular mechanisms that remain stable and functional at high temperatures, allowing them to exploit habitats that are inaccessible to most other organisms.

Furthermore, fungi are highly adaptable to nutrient-poor environments. Their extensive network of hyphae, the thread-like structures that make up their bodies, enables them to efficiently absorb nutrients from even the most depleted substrates. This efficiency is particularly evident in their role as decomposers, where they break down dead plant and animal matter, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. In symbiotic relationships, such as mycorrhizae, fungi enhance the nutrient uptake of their plant partners, ensuring mutual survival in nutrient-limited soils.

Lastly, fungi exhibit a unique ability to withstand desiccation, or extreme dryness. Many species can enter a dormant state when water is scarce, reactivating once conditions improve. This is achieved through the production of thick-walled spores and specialized structures that minimize water loss. Such adaptations allow fungi to colonize arid environments, including deserts and dry woodlands, where they play crucial roles in nutrient cycling and ecosystem stability. Collectively, these environmental adaptations underscore the versatility and resilience of fungi, making them indispensable components of virtually every ecosystem on Earth.

Are Yard Mushrooms Poisonous? Identifying Safe vs. Toxic Varieties

You may want to see also

Predator Defense Strategies: Mushrooms use toxins, bitter tastes, or camouflage to deter consumption by animals

Mushrooms have evolved a variety of predator defense strategies to ensure their survival in diverse ecosystems. One of the most effective methods is the production of toxins, which deter animals from consuming them. Many mushroom species contain poisonous compounds that can cause severe illness or even death in predators. For example, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) produces amatoxins, which are deadly to humans and many animals. These toxins act as a powerful deterrent, as predators quickly learn to avoid such mushrooms after a single unpleasant or harmful encounter. This chemical defense mechanism not only protects the individual mushroom but also safeguards its spores, ensuring the continuation of its species.

In addition to toxins, mushrooms often employ bitter tastes as a defense mechanism. Bitter compounds are unpalatable to most herbivores, making the mushroom less appealing as a food source. This strategy is particularly effective against generalist feeders that are more likely to sample a variety of plants and fungi. For instance, the Bitter Oyster (*Panellus stipticus*) has a distinctly bitter flavor that discourages consumption. Over time, animals in the ecosystem learn to associate the bitter taste with an unpleasant experience, further reducing the likelihood of predation. This simple yet effective defense allows mushrooms to thrive even in environments with high herbivore activity.

Camouflage is another critical predator defense strategy employed by mushrooms. By blending into their surroundings, mushrooms reduce their visibility to potential predators. This is achieved through coloration and texture that mimic the forest floor, decaying wood, or other natural substrates. For example, the Earthstar mushroom (*Geastrum* species) has a brown, rough exterior that resembles soil or dead leaves, making it nearly invisible to foraging animals. Similarly, some mushrooms grow in hidden or hard-to-reach locations, such as within dense clusters of vegetation or beneath logs, further minimizing their exposure to predators. Camouflage ensures that mushrooms can mature and release their spores without being detected and consumed.

Beyond these strategies, some mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with other organisms to enhance their defense capabilities. For instance, certain fungi are protected by ants or other insects that feed on the sugars they produce. In return, these insects defend the mushrooms against herbivores, creating a mutually beneficial relationship. This indirect defense mechanism highlights the complexity of mushroom survival strategies and their integration into broader ecosystem dynamics. By combining toxins, bitter tastes, camouflage, and symbiotic relationships, mushrooms effectively deter predation and secure their role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem health.

Understanding these predator defense strategies provides valuable insights into the resilience and adaptability of mushrooms. Their ability to produce toxins, develop unpalatable tastes, employ camouflage, and form protective alliances underscores their evolutionary success. These mechanisms not only protect individual mushrooms but also ensure the survival and dispersal of their species, contributing to the biodiversity and functioning of ecosystems worldwide. As decomposers and symbionts, mushrooms play a vital role in nutrient cycling, making their defense strategies essential for maintaining ecological balance.

Psilocybe Mushrooms in Washington: Where and How They Thrive

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms are fungi that obtain nutrients through absorption. They secrete enzymes to break down organic matter like dead plants, wood, or soil, and then absorb the released nutrients directly into their cells.

Mushrooms act as decomposers, breaking down complex organic materials into simpler substances, which enriches the soil and recycles nutrients for other organisms. They also form symbiotic relationships with plants, aiding in nutrient uptake.

Unlike plants, mushrooms do not require sunlight for growth. They obtain energy through heterotrophic means, relying on organic matter rather than photosynthesis.

Mushrooms reproduce by releasing spores, which are dispersed by wind, water, or animals. These spores germinate under suitable conditions, growing into new fungal networks called mycelium, which eventually produce more mushrooms.

Mushrooms thrive in moist, humid environments with organic matter. They require adequate water, moderate temperatures, and a substrate like soil, wood, or decaying plant material to grow and survive.