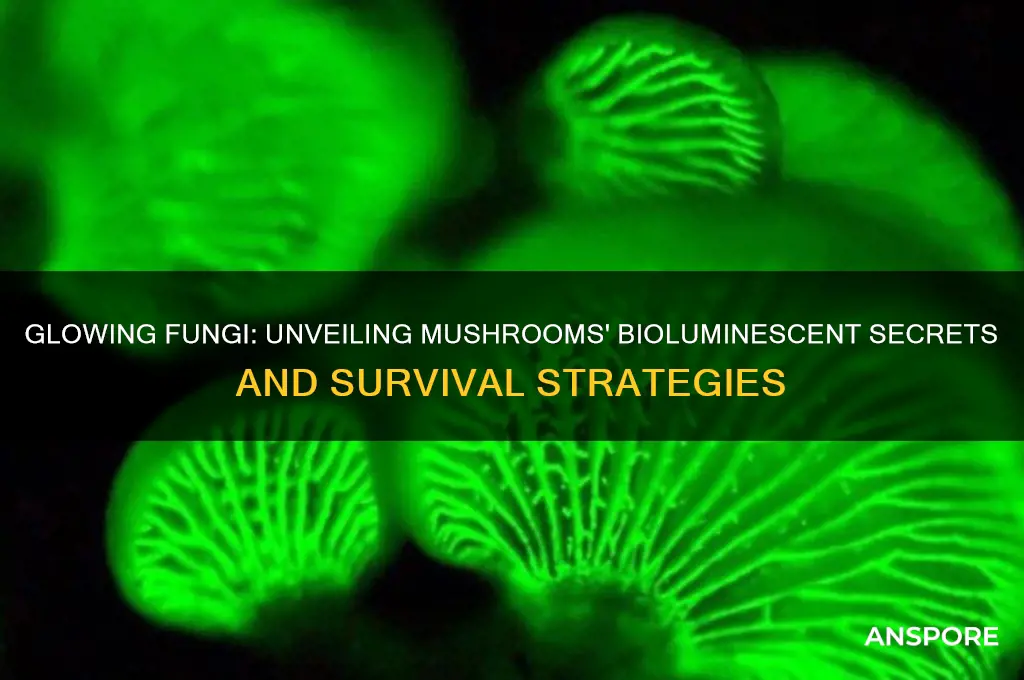

Mushrooms that exhibit bioluminescence, a phenomenon known as foxfire, produce a captivating glow through a chemical reaction involving luciferin, a light-emitting molecule, and luciferase, an enzyme that catalyzes the reaction. This process, primarily occurring in certain fungal species like *Mycena* and *Omphalotus*, serves multiple ecological purposes, such as attracting insects for spore dispersal or deterring predators. The eerie green or blue light emitted is a result of energy released during the oxidation of luciferin, with minimal heat production, making it an efficient and fascinating adaptation in the fungal kingdom.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Bioluminescence in mushrooms is produced by a chemical reaction involving luciferin (a light-emitting molecule), luciferase (an enzyme), and oxygen. This reaction occurs in specialized cells called photocytes. |

| Purpose | Primarily used to attract insects and other animals, aiding in spore dispersal. The light increases visibility, making mushrooms more noticeable to potential spore carriers. |

| Color | Most bioluminescent mushrooms emit a green light, though rare species may produce yellow, blue, or even red hues. |

| Timing | Bioluminescence is often most visible at night, as the darkness enhances the light's contrast. Some species glow continuously, while others may only emit light under specific conditions (e.g., when disturbed). |

| Species | Over 80 species of bioluminescent fungi are known, with the most famous being Mycena lux-coeli and Neonothopanus nambi. |

| Habitat | Commonly found in tropical and subtropical forests, where high humidity and organic matter support fungal growth. |

| Evolutionary Advantage | Bioluminescence is believed to have evolved as a symbiotic strategy to enhance spore dispersal, increasing the fungus's reproductive success. |

| Intensity | The brightness varies among species, ranging from faint glows visible only in complete darkness to more intense lights that can be seen from several meters away. |

| Chemical Efficiency | The bioluminescent reaction is highly efficient, with nearly 100% of the energy released as light, producing minimal heat. |

| Research Interest | Studied for potential applications in biotechnology, such as bioimaging, biosensors, and sustainable lighting solutions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Chemical reactions in mushrooms producing light

Mushrooms like the ghost fungus (*Omphalotus nidiformis*) and the jack-o’-lantern mushroom (*Mycena chlorophos*) emit a haunting green glow through bioluminescence, a process driven by specific chemical reactions. At the heart of this phenomenon is a light-emitting molecule called luciferin, which reacts with oxygen in the presence of an enzyme called luciferase. This reaction, known as the luciferin-luciferase pathway, produces oxyluciferin and releases energy in the form of light. Unlike fireflies, which use ATP (adenosine triphosphate) to fuel their bioluminescence, mushrooms rely on a steady supply of oxygen and a co-enzyme called reduced riboflavin phosphate. This unique chemistry allows them to glow continuously, often in low-light environments where photosynthesis is impossible.

To understand the mechanics, imagine a three-step process. First, luciferin is oxidized by molecular oxygen, forming an excited-state oxyluciferin. Second, this excited molecule releases a photon of light as it returns to its ground state. Finally, the oxyluciferin is reduced back to luciferin, completing the cycle. This reaction is highly efficient, with nearly 40% of the energy released as light—far more than incandescent bulbs. In mushrooms, this process occurs in specialized cells called photocytes, often concentrated in the gills or mycelium. The intensity of the glow can vary based on factors like temperature, humidity, and the mushroom’s developmental stage, with some species glowing brightest at 20–25°C (68–77°F).

One fascinating aspect of fungal bioluminescence is its evolutionary purpose, which remains debated. Some researchers suggest it attracts insects, aiding in spore dispersal, while others propose it deters predators by signaling toxicity. For instance, the ghost fungus, which grows on decaying wood, emits a bright green light that may lure insects to carry its spores. In contrast, the *Mycena lux-coeli* mushroom, found in Japan, glows faintly, possibly to confuse nocturnal predators. Practical applications of this chemistry are emerging too: scientists are exploring bioluminescent mushrooms as eco-friendly light sources or biosensors. By isolating luciferase genes, researchers have even engineered plants to glow, offering potential alternatives to electric lighting.

For enthusiasts interested in observing this phenomenon, certain conditions optimize bioluminescence. Mushrooms glow most vividly in dark, humid environments, so nighttime forest walks during rainy seasons are ideal. Avoid touching or disturbing the fungi, as this can disrupt their light emission. Photography tips include using a tripod, setting a long exposure (15–30 seconds), and increasing ISO to 1600–3200 to capture the faint glow. Apps like “Seek by iNaturalist” can help identify bioluminescent species in the wild. Remember, while these mushrooms are often non-toxic, consuming them is not recommended, as many glowing fungi are inedible or even poisonous.

In conclusion, the chemical reactions behind mushroom bioluminescence are a marvel of nature, blending efficiency with mystery. By studying these processes, we gain insights into evolutionary adaptations and potential technological innovations. Whether you’re a scientist, photographer, or nature enthusiast, understanding the luciferin-luciferase pathway transforms a simple forest glow into a window into the intricate world of fungal biology. Next time you spot a glowing mushroom, take a moment to appreciate the invisible chemistry that makes it shine.

Does Mellow Mushroom Use Butter in Their Pizza Recipes?

You may want to see also

Enzymes (luciferase) role in bioluminescence

Bioluminescence in mushrooms, a captivating natural phenomenon, relies heavily on the enzyme luciferase. This enzyme acts as the catalyst in a chemical reaction that produces light, transforming energy into a mesmerizing glow without generating heat. Found in species like *Mycena lux-coeli* and *Neonothopanus nambi*, luciferase works in tandem with a light-emitting molecule called luciferin and oxygen. When luciferin reacts with oxygen, it produces an excited state intermediate, and luciferase stabilizes this process, ensuring the energy is released as light rather than heat. This efficiency is a marvel of biochemical engineering, allowing mushrooms to emit a steady, cool luminescence in dark environments.

To understand luciferase’s role, consider it the director of a biochemical play. The enzyme binds to luciferin and oxygen, positioning them precisely for the reaction. This specificity ensures the energy transfer is directed toward light emission, a process known as bioluminescent efficiency. In mushrooms, this reaction occurs within specialized cells called photocytes, often located in the mycelium or gills. The light produced serves multiple ecological purposes, from attracting insects for spore dispersal to deterring predators. For instance, the ghost mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*) uses its bioluminescence to mimic a toxic glow, warding off potential threats.

Practical applications of luciferase extend beyond the forest floor. In biotechnology, luciferase is a cornerstone of molecular biology, used in assays to detect gene expression and monitor cellular processes. Its sensitivity allows researchers to measure minute quantities of ATP, a key energy molecule, in living cells. For example, in medical diagnostics, luciferase-based tests can detect diseases like cancer by measuring enzyme activity in tissue samples. To harness this in a lab setting, scientists often use recombinant luciferase, produced in bacteria or yeast, ensuring a consistent and scalable supply. Dosage in such experiments is critical; typically, 1-10 ng of luciferase per sample is sufficient for accurate detection, depending on the assay’s sensitivity.

Comparing luciferase across species reveals fascinating adaptations. While fungal luciferase is optimized for dim, steady light, firefly luciferase produces brighter, more transient flashes. This difference lies in the enzyme’s structure and reaction kinetics. Fungal luciferase operates continuously, maintaining a constant glow, whereas firefly luciferase is activated in bursts, tied to mating signals. Such variations highlight the enzyme’s versatility and evolutionary fine-tuning. For enthusiasts looking to observe bioluminescent mushrooms, nighttime hikes in humid, wooded areas during rainy seasons offer the best chances. Carry a UV flashlight to enhance visibility, as some species glow more vividly under ultraviolet light.

In conclusion, luciferase is the unsung hero of mushroom bioluminescence, a molecular maestro orchestrating light from chemical reactions. Its role is both ecologically vital and scientifically invaluable, bridging the gap between nature’s wonders and technological innovation. Whether in the forest or the lab, this enzyme continues to illuminate possibilities, proving that even in darkness, there is light to be found.

Were Ancient Mushrooms Gigantic? Unveiling the Mystery of Prehistoric Fungi

You may want to see also

Light emission as a defense mechanism

Bioluminescent mushrooms, often found in the dimly lit understories of forests, emit a soft, eerie glow that serves more than just an aesthetic purpose. This light, typically green or blue, is a byproduct of a chemical reaction involving luciferin (a light-emitting compound) and luciferase (an enzyme). While the exact reasons for this phenomenon vary, one compelling theory is that light emission acts as a defense mechanism. By glowing, these fungi may deter predators or attract secondary predators of their would-be attackers, creating a protective shield in the dark.

Consider the mycena lux-cooperens, a bioluminescent mushroom species that thrives in decaying wood. When threatened by slugs or insects, its glow intensifies, potentially signaling toxicity or unpalatability. This strategy, known as aposematism, is akin to the bright colors of poison dart frogs. Studies suggest that bioluminescence reduces predation rates by up to 68% in certain environments, making it an effective survival tool. For gardeners or foragers, this highlights the importance of leaving glowing fungi undisturbed, as their light may be a warning rather than an invitation.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the energy cost of bioluminescence is significant, yet its persistence suggests a strong adaptive advantage. The light emitted is cold, producing no heat, and requires minimal resources compared to other defense mechanisms like chemical production. This efficiency makes it particularly suited for fungi, which have limited mobility and rely on passive strategies. For enthusiasts studying bioluminescence, observing these mushrooms in their natural habitat can provide insights into how organisms balance energy expenditure with survival needs.

Practical applications of this defense mechanism extend beyond the forest floor. Researchers are exploring bioluminescent fungi as bioindicators of environmental health, as their glow can signal changes in habitat conditions. Additionally, the genes responsible for bioluminescence are being studied for use in sustainable lighting solutions. For DIY biohackers, cultivating bioluminescent mushrooms at home (species like *Neonothopanus nambi*) offers a hands-on way to explore this phenomenon, though caution is advised to avoid contamination and ensure proper species identification.

In conclusion, the glow of bioluminescent mushrooms is not merely a natural wonder but a sophisticated defense strategy honed over millennia. By understanding its purpose, we gain not only scientific insight but also practical guidance for conservation and innovation. Whether in the wild or a lab, these fungi remind us that even the smallest organisms can illuminate profound truths about survival and adaptation.

Using White Mushroom Stems: Tips, Benefits, and Creative Culinary Ideas

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.5

$30.19 $32.99

Attracting insects for spore dispersal

Bioluminescent mushrooms, such as the ghost mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*) and the jack-o’-lantern mushroom (*Mycena chlorophos*), emit a soft, eerie glow that serves a practical purpose beyond mere fascination. This light, produced through a chemical reaction involving luciferin and luciferase, acts as a beacon in the dark, primarily to attract insects. Unlike plants that rely on wind or animals for pollination, mushrooms depend on creatures like flies, beetles, and mosquitoes to disperse their spores. The glow mimics the allure of moonlight or decaying matter, drawing insects closer to the mushroom’s gills or pores, where spores cling to their bodies and are carried away.

To maximize spore dispersal, bioluminescent mushrooms strategically time their glow to peak during nighttime hours when insect activity is highest. Studies show that the intensity of the light correlates with spore release, suggesting a deliberate effort to synchronize attraction with dispersal. For instance, the ghost mushroom’s glow is most intense during the late evening, coinciding with the foraging patterns of nocturnal flies. Gardeners or mycologists aiming to cultivate these mushrooms for spore collection should mimic this natural rhythm by placing specimens in dimly lit areas at dusk, ensuring insects are drawn to the light source.

The mechanism behind this attraction is both simple and ingenious. Insects, particularly those with nocturnal habits, are naturally drawn to light sources, mistaking them for food, mates, or safe resting spots. Bioluminescent mushrooms exploit this behavior by emitting a wavelength of light (typically green or blue-green) that is highly visible to insects but less so to larger predators. This reduces the risk of the mushroom being consumed while increasing the likelihood of spore dispersal. For those studying or replicating this process, using UV or blue-green LED lights in controlled environments can simulate bioluminescence and attract insects effectively.

However, not all insects are equally effective spore carriers. Flies and beetles, with their hairy bodies and frequent movement, are ideal candidates, while smoother-bodied insects like mosquitoes may carry fewer spores. To optimize dispersal in a controlled setting, focus on attracting flies by placing mushrooms near ripe fruit or fermented substances, which naturally lure these insects. Additionally, ensure the environment is humid, as bioluminescent mushrooms thrive in moisture-rich conditions, and their glow intensifies when properly hydrated.

In conclusion, bioluminescence in mushrooms is a finely tuned strategy for spore dispersal, leveraging the natural behavior of insects to ensure genetic propagation. By understanding the timing, wavelength, and environmental factors that enhance this process, enthusiasts can replicate these conditions to study or cultivate bioluminescent species effectively. Whether in a forest or a laboratory, the interplay between light, insects, and mushrooms highlights the ingenuity of nature’s solutions to survival and reproduction.

Mushrooms as Medicine: Exploring Psychedelic Therapy's Healing Potential

You may want to see also

Bioluminescent species and their habitats

Bioluminescent mushrooms, often found in the dimly lit understories of tropical and temperate forests, use their glow to attract insects, which inadvertently aid in spore dispersal. This symbiotic relationship highlights how habitat and survival strategies intertwine in nature. Species like *Mycena lux-coeli* and *Neonothopanus gardneri* thrive in decaying wood and leaf litter, where their light can penetrate the darkness most effectively. These fungi are not solitary in their bioluminescent prowess; they share their habitats with other glowing organisms, such as fireflies and certain bacteria, creating a miniature ecosystem of light in the dark.

To observe these mushrooms in their natural habitat, venture into old-growth forests during humid, moonless nights. Carry a red-light flashlight to preserve your night vision without disrupting the fungi’s glow. Look for clusters on rotting logs or damp soil, where moisture levels are high—a critical factor for their growth. Avoid touching or disturbing the mushrooms, as their delicate mycelium networks are easily damaged. For enthusiasts, creating a bioluminescent garden is possible by inoculating decaying wood with spore kits, though patience is required, as fruiting bodies may take months to appear.

The habitats of bioluminescent mushrooms are under threat from deforestation and climate change, which disrupt the delicate balance of humidity and darkness they require. Conservation efforts must focus on preserving these ecosystems, not just for the fungi but for the broader biodiversity they support. For instance, *Omphalotus olearius*, found in Mediterranean forests, plays a role in nutrient cycling, breaking down wood into soil. Protecting these habitats ensures the survival of bioluminescent species and maintains the ecological functions they provide.

Comparing bioluminescent mushrooms to other glowing organisms reveals shared evolutionary pressures. While deep-sea anglerfish use light to lure prey, mushrooms attract spore dispersers, showcasing convergent evolution in light’s utility. However, mushrooms’ bioluminescence is chemically distinct, involving luciferins and luciferases unique to fungi. This specificity underscores the importance of studying these species in their native habitats, as laboratory conditions often fail to replicate the intricate interactions that drive their glow.

For educators and parents, bioluminescent mushrooms offer a captivating way to teach about ecosystems and adaptation. Organize night hikes in suitable forests, pairing observations with discussions on biodiversity and conservation. Alternatively, use glow-in-the-dark mushroom models to explain bioluminescence in classrooms. Encourage students to research local fungi and their roles in ecosystems, fostering a deeper appreciation for the unseen wonders of nature. By integrating these species into learning, we inspire the next generation to protect their habitats.

Does Rally's Use Mushroom Powder in Their Burgers? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms produce bioluminescence through a chemical reaction involving luciferin (a light-emitting molecule) and luciferase (an enzyme). When luciferin reacts with oxygen, catalyzed by luciferase, it releases energy in the form of light, typically in green, yellow, or blue hues.

The primary purpose of bioluminescence in mushrooms is believed to attract insects and other animals. By glowing in the dark, mushrooms increase their visibility, which helps disperse their spores as insects or animals come into contact with them and carry the spores to new locations.

Over 80 species of mushrooms are known to be bioluminescent, with the most famous being *Mycena lux-coeli* (ghost mushroom) and *Omphalotus olearius* (jack-o’-lantern mushroom). These species are found in various parts of the world, often in forested areas with high humidity.