Plants that reproduce via spores, such as ferns, mosses, and fungi, utilize a unique and ancient method of reproduction called alternation of generations. This process involves two distinct life stages: the sporophyte, which produces spores, and the gametophyte, which produces gametes (sex cells). Spores are typically single-celled and lightweight, allowing them to be dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates into a gametophyte, which is often smaller and simpler than the sporophyte. The gametophyte then produces male and female gametes, which fuse during fertilization to form a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This reproductive strategy enables spore-bearing plants to thrive in diverse habitats, from damp forests to arid landscapes, by efficiently colonizing new areas and adapting to environmental challenges.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Asexual (vegetative) and sexual reproduction |

| Spores Produced | Haploid spores (single set of chromosomes) |

| Spore Types | Sporangiospores (endogenous) and conidiospores (exogenous) |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations (sporophyte and gametophyte phases) |

| Sporophyte Phase | Diploid, produces spores via meiosis |

| Gametophyte Phase | Haploid, produces gametes (sperm and eggs) |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms (e.g., spore capsules) |

| Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions to form gametophytes |

| Fertilization | Sperm from male gametophyte fertilizes egg in female gametophyte |

| Examples of Plants | Ferns, mosses, liverworts, horsetails, lycophytes, fungi (though not plants, they reproduce similarly) |

| Advantages | Rapid colonization, survival in harsh conditions, genetic diversity |

| Disadvantages | Dependence on moisture for fertilization, limited dispersal range |

| Environmental Requirements | Moisture for spore germination and fertilization |

| Genetic Variation | Meiosis during spore formation introduces genetic diversity |

| Dominant Phase | Varies by group (e.g., ferns: sporophyte dominant; mosses: gametophyte dominant) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Spores develop in sporangia on plant structures like leaves or stems

- Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new environments for growth

- Germination Process: Spores land, absorb water, and sprout into gametophytes

- Gametophyte Role: Produces eggs and sperm for fertilization in moist conditions

- Sporophyte Development: Fertilized egg grows into a new spore-producing plant

Spore Formation: Spores develop in sporangia on plant structures like leaves or stems

Spores are the microscopic units of life that enable certain plants to reproduce without seeds. Unlike flowering plants that rely on pollen and ovules, spore-producing plants—such as ferns, mosses, and fungi—depend on sporangia, specialized structures where spores develop. These sporangia are typically located on plant structures like leaves, stems, or even the undersides of fronds, positioning them for efficient dispersal. This reproductive strategy is ancient, dating back to the earliest land plants, and remains a cornerstone of survival for non-seed plants today.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern as a prime example. On the underside of its fronds, clusters of sporangia form, often visible as brown or yellow dots. Within each sporangium, spores mature through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number, ensuring genetic diversity. When conditions are dry, the sporangium dries out, and the spores are launched into the air, sometimes traveling great distances. This dispersal mechanism is critical for colonizing new habitats, as spores are lightweight and can survive harsh conditions until they land in a suitable environment.

The development of spores in sporangia is a marvel of biological efficiency. Sporangia are not merely containers; they are dynamic structures that respond to environmental cues. For instance, in some species, sporangia open and close in response to humidity, ensuring spores are released only when conditions favor their survival. This precision is vital, as spores are vulnerable to desiccation and predation. Once released, spores germinate into gametophytes, the sexual phase of the plant’s lifecycle, which produces eggs and sperm. This alternation of generations—between spore-producing sporophytes and gametophytes—is a defining feature of spore-reproducing plants.

Practical observation of spore formation can be a rewarding activity for gardeners or educators. To witness this process, collect a mature fern frond with visible sporangia and place it on a sheet of white paper. Over time, the sporangia will release spores, leaving behind a pattern of dust-like particles. This simple experiment highlights the accessibility of studying plant reproduction and underscores the importance of sporangia in the lifecycle of spore-producing plants.

In conclusion, spore formation in sporangia is a sophisticated reproductive strategy that ensures the survival and dispersal of non-seed plants. By understanding the role of sporangia—whether on leaves, stems, or other structures—we gain insight into the resilience and diversity of plant life. This knowledge not only enriches our appreciation of the natural world but also informs conservation efforts and horticultural practices, ensuring these ancient plants continue to thrive.

Can Mold and Spores Survive Underwater? Exploring Aquatic Microbial Life

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new environments for growth

Spores, the microscopic units of life, are nature's ingenious solution for plant reproduction, especially in challenging environments. Their dispersal is a critical phase, ensuring the survival and spread of species across diverse habitats. Wind, water, and animals emerge as the primary agents in this process, each with unique mechanisms and implications for spore distribution.

The Wind's Invisible Hand: Imagine a gentle breeze carrying thousands of spores across vast distances. Wind dispersal, or anemochory, is a common strategy for plants like ferns and mushrooms. These plants produce lightweight spores with wings or air-filled sacs, allowing them to float effortlessly. For instance, the common bracket fungus (*Trametes versicolor*) releases spores from its underside, which are then caught by air currents. This method enables spores to travel miles, colonizing new areas, including remote or inaccessible locations. However, it's a numbers game; only a fraction of these spores will find suitable conditions for growth, emphasizing the importance of mass production.

Aqua-Dispersal: Riding the Waves: Water bodies become highways for spore transportation, particularly for aquatic plants and algae. This method is highly efficient in rivers, streams, and coastal areas. For example, the water fern (*Azolla*) produces spores that are released into the water, often sticking to animals or floating debris, which then carry them downstream. This dispersal mechanism ensures that spores reach new habitats, including areas with favorable conditions for growth, such as nutrient-rich waters. The success of this strategy lies in the spore's ability to withstand varying water conditions and its potential for long-distance travel.

Animal Couriers: Unintentional Helpers: Animals, from insects to mammals, play a pivotal role in spore dispersal, often without their knowledge. This process, known as zoochory, involves spores attaching to an animal's body and being transported to new locations. A fascinating example is the relationship between ants and certain mushroom species. Ants, attracted by a spore's lipid-rich outer layer, carry them back to their nests, where the spores can germinate in the nutrient-rich environment. Similarly, larger animals like birds and mammals can inadvertently carry spores on their fur or feathers, facilitating dispersal over significant distances. This method ensures that spores reach diverse microhabitats, increasing the chances of successful colonization.

Each dispersal method presents a unique set of advantages and challenges. While wind and water offer long-distance travel, animal dispersal provides targeted delivery to specific microenvironments. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for various applications, from conservation efforts to agriculture. For instance, in reforestation projects, knowing the natural dispersal methods of native plant species can inform strategies for seed or spore distribution, ensuring higher success rates. Moreover, studying these processes can inspire innovative solutions in fields like biotechnology, where controlled spore dispersal could revolutionize crop propagation.

In the intricate world of plant reproduction, spore dispersal is a captivating interplay of biology and physics. Whether it's the graceful dance of spores in the wind, their aquatic journeys, or their hitchhiking adventures on animals, each method contributes to the remarkable diversity and resilience of plant life. By comprehending these natural processes, we unlock valuable insights for both scientific advancement and practical applications, ensuring the continued thriving of our green companions.

Spores vs. Seeds: Which is More Effective for Plant Propagation?

You may want to see also

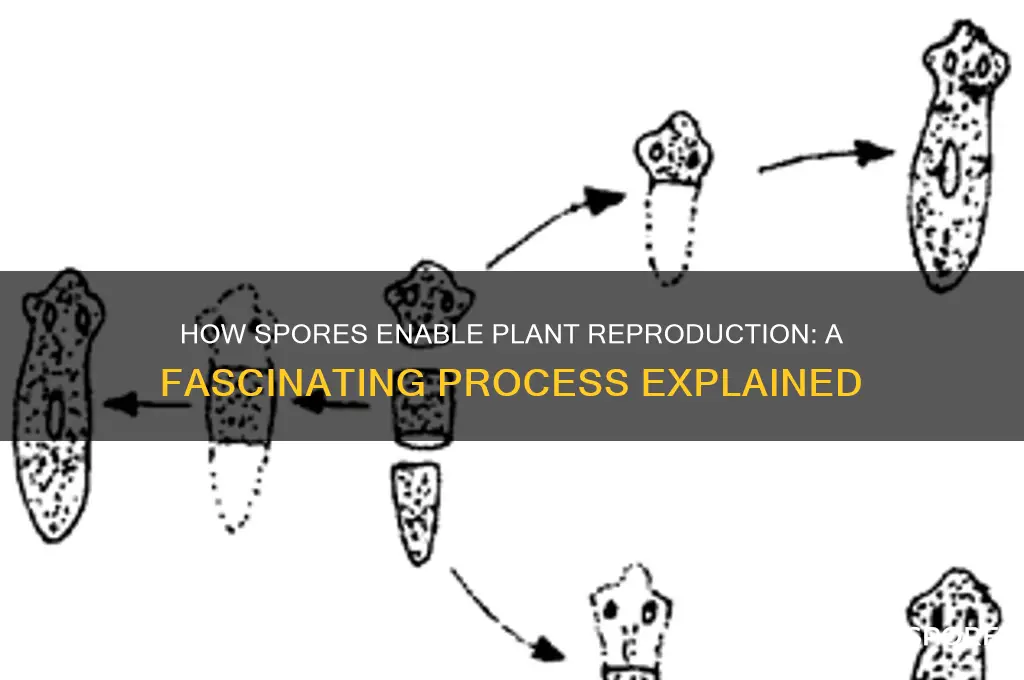

Germination Process: Spores land, absorb water, and sprout into gametophytes

Spores, the microscopic units of life for many plants, embark on a remarkable journey when they land in a suitable environment. This initial contact is crucial, as it marks the beginning of the germination process, a complex yet fascinating transformation from a dormant spore to a thriving gametophyte. The success of this stage depends on various factors, including moisture, temperature, and light conditions, which collectively create an optimal setting for growth.

Upon landing, the spore's first priority is to secure a water source. This is achieved through a process called imbibition, where the spore rapidly absorbs water from its surroundings, swelling in size and initiating metabolic activity. The amount of water required varies among species, but generally, a consistent moisture level is essential. For instance, ferns often thrive in humid environments, where spores can readily absorb moisture from the air, while mosses may rely on water-rich substrates. This hydration process triggers the activation of enzymes and nutrients stored within the spore, setting the stage for the next phase.

As the spore continues to absorb water, it begins to sprout, marking the emergence of the gametophyte. This delicate, heart-shaped structure is the sexual phase of the plant's life cycle. The sprouting process is a critical period, requiring specific conditions to ensure success. For example, some species may require a period of cold stratification, where spores are exposed to cold temperatures for several weeks, mimicking winter conditions, before they can germinate. This step is particularly important for plants in temperate regions, ensuring that growth occurs during favorable seasons.

The development of the gametophyte is a testament to the plant's adaptability and survival strategies. These small, photosynthetic organisms produce sex organs, allowing for the continuation of the species through sexual reproduction. The process is a delicate balance of environmental cues and intrinsic programming, ensuring that the plant's life cycle progresses efficiently. Understanding these intricacies is not only fascinating but also crucial for horticulture and conservation efforts, especially in the cultivation of spore-bearing plants like ferns and mosses, which are increasingly popular in landscaping and indoor gardening.

In practical terms, gardeners and botanists can encourage successful spore germination by creating a controlled environment. This includes maintaining high humidity levels, providing indirect light, and ensuring a sterile growing medium to prevent competition from other organisms. For enthusiasts, observing this process offers a unique insight into the resilience and diversity of plant life, showcasing the intricate mechanisms that have allowed spore-bearing plants to thrive for millions of years. By replicating these natural conditions, one can witness the transformation from spore to gametophyte, a microcosm of the plant kingdom's reproductive strategy.

Are Mold Spores Invisible? Unveiling the Hidden Truth About Mold

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.99

Gametophyte Role: Produces eggs and sperm for fertilization in moist conditions

In the intricate world of plant reproduction, the gametophyte plays a pivotal role, particularly in species that rely on spores. This diminutive yet vital stage of the plant life cycle is responsible for producing the eggs and sperm necessary for fertilization, a process that hinges on the presence of moisture. Unlike the more robust sporophyte phase, the gametophyte is often small, delicate, and short-lived, yet its function is indispensable. Without it, the continuation of species such as ferns, mosses, and liverworts would be impossible.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a prime example of a plant that reproduces via spores. After a spore germinates, it develops into a gametophyte, commonly known as a prothallus. This heart-shaped structure, no larger than a thumbnail, is the sexual powerhouse of the fern’s life cycle. On its underside, it produces both egg-containing archegonia and sperm-producing antheridia. For fertilization to occur, water is essential—sperm must swim from the antheridia to the archegonia, a journey that can only happen in moist conditions. This dependency on water highlights the gametophyte’s evolutionary adaptation to damp environments, such as forest floors or stream banks.

The gametophyte’s role is not merely passive; it actively creates the conditions necessary for fertilization. In mosses, for instance, the gametophyte is the dominant phase of the life cycle, forming lush green carpets in shady, humid habitats. Male gametophytes release sperm that require a water film to reach the eggs housed in the female archegonia, often located on separate plants. This external fertilization strategy underscores the gametophyte’s reliance on moisture, making it a key player in ecosystems where water is abundant. Practical tip: To observe this process, collect moss from a damp area, place it on a damp paper towel, and watch for the release of sperm under a magnifying glass during rainy periods.

Comparatively, in liverworts, the gametophyte’s structure varies but its function remains consistent. Some liverworts have male and female gametophytes that grow separately, while others are monoecious, bearing both sexes on the same plant. Regardless, the production of eggs and sperm is a gametophyte-exclusive task. Fertilization again depends on water, reinforcing the gametophyte’s role as a moisture-dependent reproductive specialist. This consistency across diverse plant groups illustrates the gametophyte’s evolutionary success in ensuring genetic continuity.

In conclusion, the gametophyte’s role in producing eggs and sperm for fertilization in moist conditions is a testament to its specialized function in the plant kingdom. Its reliance on water is not a limitation but an adaptation, enabling it to thrive in specific environments. By understanding this phase, we gain insight into the delicate balance of nature and the mechanisms that sustain plant diversity. Whether in a fern’s prothallus or a moss’s verdant mat, the gametophyte’s contribution is both subtle and profound, a reminder of the intricate relationships that drive life.

Basidia's Role in Efficient Mushroom Spore Dispersal Explained

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Development: Fertilized egg grows into a new spore-producing plant

The journey of a fertilized egg into a mature, spore-producing plant, known as the sporophyte, is a marvel of botanical development. This process begins with the fusion of gametes—sperm and egg—during fertilization, typically occurring in the archegonium of a gametophyte. The resulting zygote, now a diploid cell, marks the inception of the sporophyte generation. Unlike the gametophyte, which is haploid and often smaller, the sporophyte is the dominant phase in many plant life cycles, particularly in ferns, mosses, and seedless vascular plants. This transition from a single cell to a complex, multicellular organism is a testament to the intricate regulatory mechanisms governing plant growth.

As the zygote divides, it develops into an embryo, which eventually grows into a sporophyte. This growth is fueled by nutrients stored in the gametophyte, highlighting the interdependence between these two generations. In ferns, for instance, the young sporophyte remains attached to the gametophyte until it can photosynthesize independently. This early stage is critical, as the sporophyte must establish its vascular system to transport water and nutrients efficiently. The development of true roots, stems, and leaves distinguishes the sporophyte from the simpler gametophyte, showcasing the plant’s increasing complexity and self-sufficiency.

The maturation of the sporophyte culminates in the production of spores, ensuring the continuation of the species. Spores are formed within specialized structures like sporangia, which develop on the sporophyte’s leaves or stems. In ferns, these spore-bearing structures are often clustered into sori, protected by a thin membrane called the indusium. The type of spores produced—whether identical (homosporous) or differing in size and function (heterosporous)—influences the subsequent gametophyte generation. For example, heterosporous plants produce microspores and megaspores, which develop into male and female gametophytes, respectively, adding a layer of reproductive strategy.

Practical observation of sporophyte development can be a rewarding experience for botanists and enthusiasts alike. To witness this process, collect mature spores from a fern frond and sow them on a moist, sterile medium. Under controlled conditions, the spores will germinate into gametophytes, which, when watered with a fine mist to simulate natural conditions, may facilitate fertilization and sporophyte growth. Patience is key, as this process can take weeks to months, depending on the species. For educators, this experiment offers a tangible way to demonstrate alternation of generations, a fundamental concept in plant biology.

In conclusion, sporophyte development is a fascinating interplay of cellular division, nutrient utilization, and structural differentiation. From the fertilized egg to the spore-producing plant, each stage is a carefully orchestrated step toward ensuring the plant’s survival and propagation. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation for plant life but also provides practical insights into cultivation and conservation efforts. Whether in a laboratory or a forest, observing sporophyte development connects us to the intricate rhythms of the natural world.

How Christianity Spread: Missionaries, Empires, and Cultural Adaptation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Plants that reproduce via spores, such as ferns, mosses, and fungi, undergo a process called sporulation. Spores are tiny, single-celled reproductive units produced in structures like sporangia. When conditions are favorable, spores germinate and grow into new individuals without the need for seeds or pollination.

Spore-producing plants, like ferns, have an alternation of generations life cycle. This involves two phases: the sporophyte (diploid) phase, which produces spores, and the gametophyte (haploid) phase, which produces gametes (sperm and eggs). Spores develop into gametophytes, which then reproduce sexually to form new sporophytes.

No, not all plants reproduce using spores. Vascular plants like flowering plants (angiosperms) and conifers (gymnosperms) reproduce using seeds, while non-vascular plants (e.g., mosses, liverworts) and some vascular plants (e.g., ferns) reproduce using spores. Fungi also reproduce via spores but are not plants.