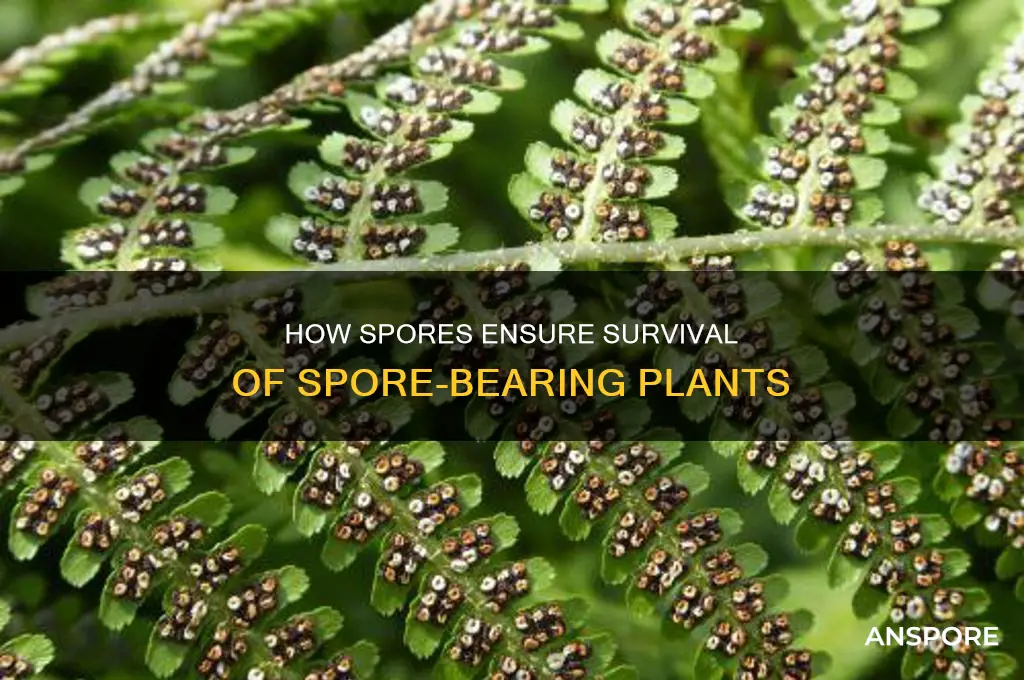

Spores play a crucial role in the survival and propagation of spore-bearing plants, such as ferns, mosses, and fungi, by serving as highly resilient reproductive units. Unlike seeds, spores are typically single-celled and lack stored nutrients, but they compensate with remarkable durability, enabling them to withstand harsh environmental conditions like extreme temperatures, drought, and radiation. This adaptability allows spore-bearing plants to colonize diverse habitats, from arid deserts to dense forests. Spores are also lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals, increasing their chances of reaching favorable environments for germination. Once conditions become suitable, spores can quickly develop into new individuals, ensuring the species' continuity even if the parent plant perishes. This efficient dispersal and survival mechanism makes spores a key factor in the long-term success and ecological resilience of spore-bearing plants.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lightweight and Dispersal | Spores are tiny and lightweight, allowing wind, water, or animals to carry them over long distances. |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments arise. |

| Rapid Reproduction | Spores enable quick colonization of new habitats, ensuring survival in changing environments. |

| Genetic Diversity | Spores often result from meiosis, promoting genetic variation and adaptability to diverse conditions. |

| Resistance to Extremes | Spores have thick cell walls that protect against desiccation, heat, cold, and other environmental stresses. |

| Low Resource Requirement | Spores require minimal nutrients and energy for production, allowing plants to allocate resources to survival. |

| Asexual and Sexual Reproduction | Spores facilitate both asexual (vegetative) and sexual reproduction, increasing survival strategies. |

| Longevity | Spores can remain viable in soil or other substrates for years, ensuring long-term survival of the species. |

| Adaptability to Niches | Spores can colonize diverse habitats, from soil and water to decaying matter, enhancing survival chances. |

| Efficient Colonization | Spores can quickly establish new populations in disturbed or nutrient-poor environments. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are lightweight, enabling wind, water, or animals to carry them over long distances

- Dormancy and Resilience: Spores can remain dormant for years, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments return

- Genetic Diversity: Spores facilitate genetic recombination, increasing adaptability and survival in changing ecosystems

- Rapid Colonization: Spores germinate quickly, allowing spore-bearing plants to colonize new habitats efficiently

- Protection from Predators: Spores' small size and hard outer walls protect them from being consumed by predators

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are lightweight, enabling wind, water, or animals to carry them over long distances

Spores, by virtue of their minuscule size and negligible weight, are nature’s masterclass in passive dispersal. Weighing mere micrograms, a single spore can be lofted by the gentlest breeze, carried in water currents, or hitch a ride on an animal’s fur without expending any energy. This lightweight design is no accident—it’s an evolutionary strategy that maximizes the chances of a spore-bearing plant colonizing new habitats. For instance, ferns release spores so tiny that a single breath could carry thousands, ensuring that even distant, isolated environments have the potential to support new growth.

Consider the practical implications for gardeners or conservationists: when reintroducing spore-bearing plants to degraded ecosystems, timing spore release with prevailing winds or water flow can exponentially increase success rates. For example, releasing fern spores during the early morning, when dew points are high and air currents are steady, can mimic natural dispersal patterns. Similarly, placing spore-bearing plants near water bodies allows spores to be carried downstream, colonizing riverbanks and wetlands with minimal intervention.

The efficiency of spore dispersal isn’t just about distance—it’s about reaching diverse environments. Wind-dispersed spores can travel miles, but water-borne spores excel in aquatic or humid settings, while animal-carried spores gain access to sheltered microhabitats. This multi-modal approach ensures that spore-bearing plants aren’t limited to a single niche. Take mosses, for example: their spores adhere to animal fur or feathers, allowing them to colonize tree bark, rocky outcrops, or even urban rooftops. This adaptability is why spore-bearing plants thrive in environments as varied as rainforests and tundra.

However, reliance on external forces for dispersal isn’t without risk. Spores are vulnerable to desiccation, predation, and environmental extremes during transit. To mitigate this, some plants produce spores with protective coatings or release them in clusters, increasing the odds that at least a few will survive the journey. For those cultivating spore-bearing plants, creating a humid, sheltered environment during spore release can mimic natural conditions and improve germination rates.

In essence, the lightweight nature of spores transforms environmental forces into allies, turning wind, water, and animals into unwitting partners in plant survival. This strategy not only ensures the species’ persistence but also its proliferation across ecosystems. Whether you’re a botanist, a gardener, or simply an observer of nature, understanding these mechanisms highlights the elegance of spore-bearing plants’ survival tactics—a testament to the ingenuity of evolution.

Isopropyl Alcohol's Effectiveness Against Fungal Spores: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Dormancy and Resilience: Spores can remain dormant for years, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments return

Spores are nature’s time capsules, engineered to endure adversity. Unlike seeds, which often require immediate germination, spores can enter a state of dormancy, suspending metabolic activity to survive extreme conditions. This biological pause allows them to withstand drought, freezing temperatures, and even radiation, ensuring the plant’s genetic lineage persists when adult organisms cannot. For example, *Selaginella lepidophylla*, a desert plant, produces spores that remain viable for decades, reviving only when rain returns. This resilience is not just a survival tactic—it’s a strategic adaptation that outpaces environmental unpredictability.

Consider the practical implications of spore dormancy for conservation and agriculture. In regions prone to erratic climates, spore-bearing plants like ferns and mosses act as ecological anchors, recolonizing disturbed areas once conditions improve. Gardeners and land managers can harness this trait by storing spores in controlled environments, then reintroducing them during restoration projects. For instance, *Sphagnum* moss spores, known to survive over 20 years in dry storage, are used to rehabilitate peatlands. To maximize success, spores should be stored in airtight containers at 4°C (39°F) with silica gel to maintain low humidity, ensuring viability until deployment.

The mechanism behind spore dormancy is a marvel of evolutionary efficiency. Unlike animals, which migrate or hibernate, spore-bearing plants rely on desiccation tolerance and robust cell walls to halt deterioration. Some spores, like those of the *Ceratopteris* fern, produce trehalose, a sugar that stabilizes cellular structures during dehydration. This biochemical fortitude allows spores to endure not just years, but millennia—viable *Lotus* spores have been recovered from sediments over 1,000 years old. Such longevity underscores the spore’s role as a genetic archive, preserving biodiversity across epochs.

However, dormancy is not without risks. Prolonged inactivity can lead to genetic stagnation, reducing adaptability to new threats. Additionally, spores rely on dispersal mechanisms like wind or water to reach favorable habitats, which can be limited in fragmented ecosystems. Conservationists must therefore balance preservation with active dispersal strategies, such as aerial seeding or creating wildlife corridors. For home gardeners, encouraging spore-bearing plants like horsetails or clubmosses can enhance soil resilience, but avoid over-harvesting wild populations, as this disrupts natural recovery cycles.

In essence, spore dormancy is a testament to life’s tenacity, a strategy that transforms vulnerability into opportunity. By understanding and replicating these mechanisms, we can safeguard ecosystems against climate volatility and human disruption. Whether restoring wetlands or cultivating shade gardens, spores remind us that survival often lies in waiting—not for the storm to pass, but for the soil to welcome new beginnings. Their resilience is not just a biological trait, but a lesson in patience and persistence.

Do All Mushrooms Have Spores? Unveiling the Fungal Truth

You may want to see also

Genetic Diversity: Spores facilitate genetic recombination, increasing adaptability and survival in changing ecosystems

Spores, the microscopic units of life produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, are not just a means of reproduction but a powerful tool for genetic diversity. Unlike seeds, which carry the genetic material of two parents, spores can undergo a unique process called alternation of generations, allowing for both asexual and sexual reproduction. This dual capability is key to their role in fostering genetic recombination, a process that shuffles and recombines genetic material, creating new combinations of traits.

Consider the life cycle of a fern. In the sporophyte generation, spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating genetically unique spores. These spores then grow into gametophytes, which can reproduce asexually or sexually. When sexual reproduction occurs, the fusion of gametes from different gametophytes results in a new sporophyte with a distinct genetic makeup. This constant mixing and matching of genetic material through spores enables fern populations to adapt rapidly to changing environments, whether it’s a shift in temperature, humidity, or soil conditions.

The practical implications of this genetic recombination are profound. For instance, in ecosystems prone to disturbances like wildfires or deforestation, spore-bearing plants can recolonize areas quickly, thanks to their ability to disperse widely and adapt genetically. A study on *Pteridium aquilinum* (bracken fern) showed that populations exposed to varying environmental stresses exhibited higher genetic diversity, correlating with increased survival rates. This adaptability is not just a theoretical advantage; it’s a survival mechanism that has allowed spore-bearing plants to thrive for millions of years, even through mass extinction events.

To harness this benefit in conservation efforts, ecologists recommend preserving habitats that support diverse spore-bearing plant populations. For gardeners or hobbyists cultivating ferns or mosses, encouraging spore dispersal across different environments can enhance genetic diversity. For example, transferring spores from a shaded, moist area to a partially sunny spot can introduce genetic variation, making the population more resilient. However, caution must be exercised to avoid introducing invasive species or disrupting native ecosystems.

In conclusion, spores are not merely reproductive units but catalysts for genetic innovation. By facilitating recombination, they ensure that spore-bearing plants remain dynamic and responsive to ecological changes. This mechanism underscores the importance of protecting these plants, not just for their intrinsic value but for their role in maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem stability. Whether in a laboratory, garden, or wilderness, understanding and supporting this process can contribute to the long-term survival of these ancient organisms.

Exploring Spore-Based Plants: Do They Feature Hanging Roots?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Rapid Colonization: Spores germinate quickly, allowing spore-bearing plants to colonize new habitats efficiently

Spores are nature's rapid response team for plant colonization. Unlike seeds, which often require specific conditions and time to germinate, spores can spring to life almost immediately upon landing in a suitable environment. This speed is crucial for spore-bearing plants, such as ferns and mosses, to establish themselves in new habitats before competitors take hold. For instance, after a forest fire, fern spores can germinate within days, quickly covering the ash-rich soil and preventing erosion while securing nutrients for growth.

Consider the process as a race against time. When a disturbance like a landslide or deforestation creates an open area, spore-bearing plants have a head start. Their lightweight spores travel easily on wind or water, dispersing widely and settling in diverse locations. Once in place, these spores can germinate within hours to days under favorable conditions—moisture, warmth, and light. This rapid germination ensures that spore-bearing plants can exploit transient opportunities, such as temporary water pools or freshly exposed soil, before they disappear or are claimed by other species.

To maximize this advantage, gardeners and conservationists can mimic natural conditions to encourage spore germination. For example, when reintroducing mosses to a barren area, ensure the substrate is consistently moist but not waterlogged. Apply a thin layer of shade cloth to retain moisture and protect young sporelings from harsh sunlight. For ferns, scatter spores on a mix of peat and sand, mist regularly, and maintain a temperature of 70–75°F (21–24°C) for optimal growth. These steps replicate the post-disturbance environments where spores thrive, accelerating colonization.

The efficiency of spore germination also highlights its evolutionary brilliance. By forgoing the energy-intensive development of seeds, spore-bearing plants invest in quantity and speed. A single fern can release millions of spores annually, ensuring that even if most fail, enough will succeed to sustain the species. This strategy is particularly effective in unpredictable environments, such as floodplains or volcanic slopes, where rapid colonization is essential for survival. In contrast, seed-bearing plants often rely on stored resources within seeds, which delays germination but provides greater resilience in stable habitats.

Ultimately, the rapid colonization enabled by spore germination is a testament to the adaptability of spore-bearing plants. Their ability to quickly exploit new habitats not only ensures their survival but also plays a vital role in ecosystem recovery. Whether stabilizing soil after a landslide or greening a post-fire landscape, these plants demonstrate how speed and efficiency can be as powerful as strength and size in the natural world. For anyone working in restoration or horticulture, understanding and leveraging this trait can turn barren spaces into thriving ecosystems with remarkable speed.

Do Nonvascular Spores Contain Chloroplasts? Unveiling Plant Cell Mysteries

You may want to see also

Protection from Predators: Spores' small size and hard outer walls protect them from being consumed by predators

Spores, with their diminutive size and robust outer walls, serve as nature’s ingenious solution to the predation pressures faced by spore-bearing plants. Measuring often less than 50 micrometers in diameter, spores are too small to be detected or efficiently consumed by most herbivores, which typically target larger, more nutrient-dense plant structures like leaves or seeds. This size advantage is compounded by their hard, resilient outer walls, composed of materials like sporopollenin, which deter even microscopic predators such as fungi or bacteria. Together, these traits create a protective barrier that ensures spores can persist in environments where larger plant parts would be swiftly devoured.

Consider the lifecycle of ferns, a prime example of spore-bearing plants. When ferns release spores into the environment, these microscopic units are virtually invisible to grazing animals. Even if ingested accidentally, the spores’ tough outer walls resist digestion, allowing them to pass through predators unharmed. This dual defense mechanism—small size and hard walls—ensures that a significant portion of spores remain viable, ready to germinate when conditions are favorable. Without such protection, ferns and other spore-bearing plants would face higher mortality rates, jeopardizing their reproductive success.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the development of these protective features in spores is a testament to the pressures of predation. Over millions of years, spore-bearing plants have refined their reproductive strategies to minimize losses to predators. The hard outer walls, for instance, are not merely a physical barrier but also a chemical one, often containing compounds that repel or inhibit predators. This multi-layered defense system highlights the adaptability of spore-bearing plants, which thrive in diverse ecosystems, from dense forests to arid deserts, thanks to their spores’ resilience.

Practical observations underscore the effectiveness of these adaptations. In laboratory studies, spores exposed to common predators like soil nematodes or fungal hyphae show significantly higher survival rates compared to unprotected plant cells. For gardeners or conservationists working with spore-bearing plants, understanding this protective mechanism can inform strategies for propagation and preservation. For instance, when cultivating ferns or mosses, ensuring spores are dispersed in environments with minimal predation pressure maximizes their chances of successful germination.

In conclusion, the small size and hard outer walls of spores are not merely incidental traits but critical survival tools. By evading detection and resisting consumption, spores ensure the continuity of spore-bearing plants in ecosystems where predation is a constant threat. This natural defense mechanism not only safeguards individual plants but also contributes to the broader biodiversity of habitats where these plants thrive. For anyone studying or working with spore-bearing plants, appreciating this protective strategy offers valuable insights into their resilience and longevity.

Unveiling the Microscopic World: Understanding the Size of Bacterial Spores

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are highly resistant structures that allow spore-bearing plants to survive extreme conditions such as drought, heat, or cold. Their tough outer walls protect the genetic material, enabling the plant to remain dormant until favorable conditions return, ensuring long-term survival.

Spores are lightweight and easily carried by wind, water, or animals, allowing spore-bearing plants to disperse over vast distances. This increases their chances of colonizing new habitats and reduces competition for resources in their original location.

Spores are asexual reproductive units that can develop into new plants without fertilization. This method of reproduction allows spore-bearing plants to quickly multiply and establish themselves in diverse environments, even in the absence of pollinators or mates.