Spores are a remarkable reproductive strategy employed by various organisms, including fungi, plants, and some bacteria, to ensure their survival and dispersal. Unlike seeds, spores are typically single-celled and lack the stored nutrients found in plant seeds, making them lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Reproduction via spores involves a process called sporulation, where the parent organism produces spores through either asexual or sexual means. Asexual spores, such as conidia in fungi, are genetically identical to the parent and are produced rapidly in favorable conditions. In contrast, sexual spores, like zygospores or ascospores, result from the fusion of gametes and exhibit genetic diversity, enhancing adaptability. Once released, spores can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal environmental conditions to germinate and grow into new individuals, ensuring the species' persistence across diverse and challenging habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Asexual (primarily) |

| Process | Sporulation (formation of spores within a sporangium) |

| Sporangium | Specialized structure where spores develop |

| Types of Spores | Endospores (bacterial), Conidia (fungal), Spores (plant) |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, animals, explosive discharge (e.g., Pilobolus fungi) |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions |

| Germination | Spores activate and grow into new organisms under favorable conditions |

| Genetic Variation | Limited in asexual spores; some fungi produce sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) for genetic diversity |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals |

| Examples | Bacteria (endospores), Fungi (conidia, zygospores), Plants (pollen, fern spores) |

| Ecological Role | Key for survival, dispersal, and colonization in diverse environments |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How spores form within sporangia through cell division and differentiation

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, and other methods spores use to spread

- Germination Triggers: Environmental cues like moisture, light, and temperature that activate spore growth

- Asexual vs. Sexual Spores: Differences in reproduction methods and genetic diversity in spores

- Survival Strategies: How spores withstand harsh conditions, such as desiccation and extreme temperatures

Sporulation Process: How spores form within sporangia through cell division and differentiation

Spores are nature’s survival capsules, engineered to endure harsh conditions until they can germinate and grow. But how do these resilient structures form? The sporulation process begins within a specialized structure called the sporangium, where a single cell undergoes a series of divisions and transformations to produce multiple spores. This intricate process is a marvel of cellular differentiation, ensuring the continuation of species in environments where seeds or vegetative growth would fail.

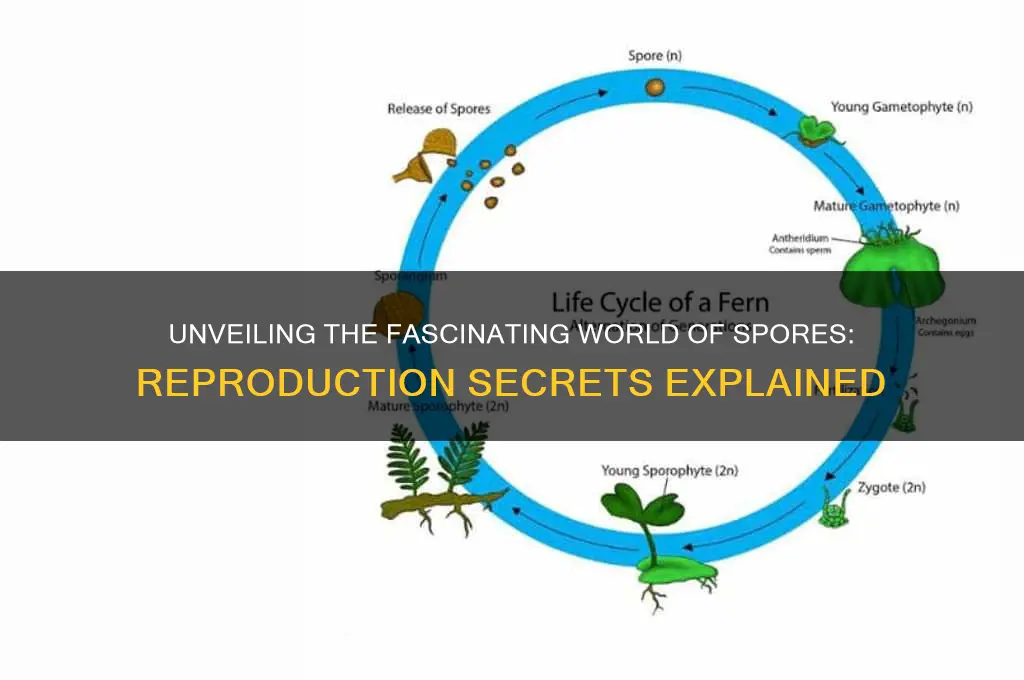

The first step in sporulation is the initiation of cell division within the sporangium. Unlike typical cell division, which produces identical daughter cells, sporulation involves asymmetric divisions that create cells with distinct fates. In fungi, for example, a diploid zygote nucleus undergoes meiosis to form haploid nuclei, which then divide mitotically to produce spore progenitors. In plants like ferns, a sporophyte cell divides to form spore mother cells, each destined to become a spore. This division is tightly regulated by environmental cues, such as nutrient scarcity or desiccation, which signal the need for spore production.

Differentiation follows division, as spore progenitors develop thick, protective walls and accumulate storage compounds like lipids and proteins. This transformation is critical for spore survival, enabling them to withstand extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemical stresses. In bacteria, such as *Bacillus subtilis*, sporulation involves the formation of an endospore within the mother cell, which eventually lyses to release the spore. The endospore’s coat is composed of multiple layers, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and an outer exosporium, providing a nearly indestructible barrier.

Practical applications of sporulation are vast, from preserving microbial cultures in labs to understanding plant reproduction in agriculture. For instance, gardeners can encourage fern sporulation by maintaining high humidity and indirect light, ensuring the sporangia on the undersides of fronds mature successfully. In biotechnology, spores of *B. subtilis* are used as models for studying stress resistance, with potential applications in food preservation and astrobiology.

In conclusion, the sporulation process is a testament to the adaptability of life. Through precise cell division and differentiation within sporangia, organisms produce spores capable of surviving conditions that would destroy most life forms. Whether in a petri dish, a forest floor, or the vacuum of space, spores embody the resilience and ingenuity of nature’s design.

Hydrogen Peroxide's Power: Can It Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, and other methods spores use to spread

Spores, the microscopic units of life, rely on ingenious dispersal mechanisms to ensure their survival and propagation. Among these, wind stands out as a primary agent, whisking spores away from their parent organism to colonize new territories. Fungi like the common puffball exemplify this strategy, releasing clouds of spores that can travel miles when caught in air currents. Lighter than dust, these spores are designed for aerodynamic efficiency, often featuring ridges or wings that enhance their flight capabilities. For gardeners and farmers, understanding this mechanism is crucial: windborne spores can quickly infest crops or spread beneficial fungi, depending on the species. To mitigate unwanted dispersal, consider using windbreaks or monitoring weather patterns during spore release seasons.

Water, another vital dispersal medium, plays a dual role in spore transportation. Aquatic plants and algae release spores into rivers, lakes, or oceans, where currents carry them to distant habitats. For instance, fern spores, though primarily wind-dispersed, can also hitch a ride on raindrops or surface water, ensuring they reach moist, shaded areas ideal for germination. In agricultural settings, irrigation systems inadvertently aid this process, spreading spores across fields. To harness this mechanism, farmers can strategically water spore-rich areas during planting seasons, promoting the growth of beneficial microorganisms. Conversely, controlling water flow can limit the spread of pathogens, such as those causing root rot in crops.

Animals, often unwitting accomplices, contribute significantly to spore dispersal. Spores cling to fur, feathers, or skin, traveling vast distances as animals migrate or forage. A classic example is the burr-like spores of certain fungi, which attach to passing deer or birds. Even humans play a role, inadvertently carrying spores on shoes or clothing into new environments. For conservationists, this mechanism highlights the interconnectedness of ecosystems, as animals act as vectors for plant and fungal diversity. To encourage beneficial spore dispersal, creating wildlife corridors or planting spore-rich vegetation near animal habitats can be effective. Conversely, in controlled environments like greenhouses, minimizing animal access reduces the risk of unwanted spore introduction.

Beyond wind, water, and animals, spores employ other creative methods to spread. Some fungi eject spores with explosive force, launching them into the air like tiny projectiles. Others, like the stinkhorn fungus, produce foul odors that attract flies, which then carry spores on their bodies. Even human activities, such as digging or mowing, can disturb soil-dwelling spores, releasing them into the environment. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, mimicking these natural processes—such as using spore syringes or creating humid, disturbed environments—can enhance success rates. However, caution is advised: disturbing spore-rich areas without protective gear can lead to respiratory issues or allergic reactions, particularly for individuals with sensitivities. Understanding these mechanisms not only aids in spore cultivation but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the resilience and adaptability of these microscopic survivors.

Unveiling the Truth: Does Moss Have Spores and How Do They Spread?

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: Environmental cues like moisture, light, and temperature that activate spore growth

Spores, the resilient survival units of various organisms, remain dormant until specific environmental cues awaken them. These germination triggers—moisture, light, and temperature—act as nature’s alarm clock, signaling the spore to emerge from its dormant state and initiate growth. Understanding these cues is crucial for fields like agriculture, conservation, and even space exploration, where controlling spore activation can mean the difference between life and stagnation.

Moisture: The Universal Catalyst

Water is the most critical trigger for spore germination across species, from fungi to ferns. Spores absorb moisture, rehydrating their cellular structures and reactivating metabolic processes. For example, fungal spores require a relative humidity of at least 90% to germinate, while fern spores often need a thin film of water on their surface. Practical tip: Gardeners can mimic this by misting soil lightly before sowing spore-based seeds, ensuring even moisture distribution without waterlogging.

Light: The Subtle Signal

Light acts as a more nuanced trigger, influencing germination in specific spore types. Some fungal spores, like those of *Neurospora crassa*, require exposure to light—particularly blue wavelengths (450–470 nm)—to break dormancy. Conversely, certain plant spores, such as those of mosses, may inhibit germination under intense light to avoid desiccation. For lab settings, researchers use LED lights with precise wavelength outputs to control germination rates, a technique adaptable for home growers with grow lights.

Temperature: The Goldilocks Factor

Temperature plays a dual role, acting as both activator and inhibitor. Most spores germinate optimally within a narrow range—typically 20–30°C (68–86°F) for fungal species and slightly cooler for some plant spores. Extreme temperatures can either accelerate germination (e.g., brief heat shocks of 50°C for *Aspergillus* spores) or halt it entirely. Caution: Prolonged exposure above 40°C can denature spore proteins, rendering them nonviable. For home experiments, use a thermostat-controlled incubator to maintain precise conditions.

Synergy of Cues: Nature’s Fail-Safe

In the wild, spores rarely encounter cues in isolation. Moisture, light, and temperature often interact synergistically to ensure germination occurs under optimal conditions. For instance, *Alternaria* spores require both water and temperatures above 15°C to sprout, while light exposure enhances their growth rate. This redundancy minimizes false starts, ensuring spores only activate when survival is likely. Takeaway: When cultivating spore-based organisms, replicate these combined cues for higher success rates—think humid, warm, and softly lit environments.

Practical Application: Controlling Spore Behavior

Understanding germination triggers allows for precise manipulation of spore behavior. Farmers can suppress fungal pathogens by maintaining dry, cool storage conditions for crops, while mycologists can induce rapid mushroom growth by providing warm, damp, and dimly lit environments. Even in space, NASA researchers study spore germination under microgravity and LED lighting to explore extraterrestrial agriculture. By mastering these cues, we harness spores’ potential while mitigating their risks, turning environmental triggers into tools for innovation.

Best Time to Apply Milky Spore for Grub Control in Lawns

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Asexual vs. Sexual Spores: Differences in reproduction methods and genetic diversity in spores

Spores, the microscopic units of life, employ two primary strategies for reproduction: asexual and sexual. Asexual spores, produced by a single parent, replicate through mitosis, yielding genetically identical offspring. This method ensures rapid proliferation under favorable conditions, as seen in fungi like *Penicillium* and *Aspergillus*. In contrast, sexual spores result from the fusion of gametes, combining genetic material from two parents. This process, observed in organisms such as ferns and certain fungi, introduces genetic diversity, enhancing adaptability to changing environments.

Consider the lifecycle of a fungus like *Rhizopus*, which alternates between asexual and sexual reproduction. Asexual spores, or sporangiospores, are produced in abundance within sporangia, dispersing quickly to colonize new habitats. This efficiency is ideal for stable environments. However, when conditions deteriorate, *Rhizopus* shifts to sexual reproduction, forming zygospores through the fusion of specialized hyphae. These zygospores, genetically diverse, can withstand harsh conditions, ensuring survival until favorable circumstances return.

The choice between asexual and sexual reproduction hinges on environmental cues. Asexual spores dominate in nutrient-rich, stable settings, where rapid colonization is advantageous. For instance, mold spores in a damp kitchen spread swiftly, exploiting abundant resources. Sexual spores, however, emerge in response to stress, such as nutrient depletion or temperature extremes. This strategy, exemplified by the formation of ascospores in *Saccharomyces* yeast, safeguards genetic variability, critical for long-term survival.

Genetic diversity is a key differentiator. Asexual spores, clones of the parent, lack variability, making populations vulnerable to diseases or environmental shifts. Sexual spores, through recombination and mutation, generate unique genetic combinations. This diversity is evident in ferns, where sexually produced spores give rise to gametophytes with varied traits, increasing the species’ resilience. For gardeners cultivating ferns, ensuring access to both male and female gametophytes can enhance genetic robustness, leading to healthier plants.

In practical terms, understanding these reproductive methods aids in controlling spore-producing organisms. For example, preventing mold growth in homes involves eliminating moisture, a trigger for asexual spore production. Conversely, disrupting sexual reproduction in pests like rust fungi requires targeting specific environmental conditions, such as temperature or light, that induce spore fusion. By manipulating these factors, one can manage spore populations effectively, whether in agriculture, conservation, or household maintenance.

Do All Bacillus Species Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Survival Strategies: How spores withstand harsh conditions, such as desiccation and extreme temperatures

Spores, the resilient survival units of various organisms, employ remarkable strategies to endure desiccation and extreme temperatures. These microscopic structures, produced by bacteria, fungi, and plants, enter a state of dormancy, reducing metabolic activity to near zero. This metabolic shutdown minimizes water and energy requirements, enabling spores to survive in environments where active life forms would perish. For instance, bacterial endospores can remain viable for centuries, waiting for conditions to improve before reactivating.

One key survival mechanism is the spore’s robust cell wall composition. In fungi, spore walls contain chitin and melanin, which provide structural strength and protect against UV radiation. Bacterial endospores have an additional layer called the exosporium, composed of proteins and lipids, which acts as a barrier against heat, chemicals, and desiccation. These layers are not just physical shields but also regulate water retention, preventing complete dehydration while allowing spores to tolerate arid conditions.

Another critical adaptation is the accumulation of protective molecules within the spore. Trehalose, a sugar found in many fungal and plant spores, stabilizes cell membranes and proteins during drying, acting like a natural antifreeze. Similarly, bacterial spores produce dipicolinic acid, which binds calcium ions to protect DNA from heat and radiation damage. These molecules are essential for maintaining cellular integrity under stress, ensuring spores can revive when conditions improve.

Practical applications of spore survival strategies are evident in food preservation and biotechnology. For example, understanding how spores resist heat has led to more effective sterilization techniques in the food industry, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes to destroy bacterial endospores. Conversely, researchers are exploring spore resilience to develop hardier crop varieties that can withstand drought and extreme temperatures, addressing agricultural challenges in a changing climate.

In summary, spores’ ability to withstand harsh conditions hinges on their structural fortifications, metabolic dormancy, and internal protective compounds. These adaptations not only ensure their survival across millennia but also offer valuable insights for industries ranging from food safety to agriculture. By studying these strategies, we unlock potential solutions to some of the most pressing challenges in science and technology.

Understanding Mold Spores: Size in Microns and Health Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores reproduce through a process called sporulation, where they germinate under favorable conditions, grow into a new organism, and eventually produce more spores.

Spores are typically a form of asexual reproduction, as they are produced by a single parent without the fusion of gametes.

Spores require moisture, warmth, and nutrients to germinate and begin the reproductive process.

No, only certain plants (like ferns and mosses) and fungi (like mushrooms) reproduce using spores, while others use seeds or other methods.

Spores are single-celled and asexual, while seeds are multicellular, contain an embryo, and are typically the result of sexual reproduction.