Trees, particularly those in the division of ferns and some gymnosperms, reproduce through the release of spores, a process distinct from the more common seed-based reproduction. Unlike flowering plants that rely on seeds for propagation, these trees produce spores in structures such as sporangia, often located on the undersides of their leaves or fronds. When mature, the sporangia release spores into the air, which are then dispersed by wind or water. Upon landing in a suitable environment, a spore germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces reproductive cells. Through fertilization, the gametophyte gives rise to a new tree, completing the life cycle. This method of reproduction is highly efficient in moist, shaded environments, where spores can thrive and develop into new generations of trees.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Asexual (via spores) |

| Trees Involved | Primarily ferns, some conifers (e.g., cycads), and a few angiosperms (e.g., certain species of palms) |

| Spores Produced | Haploid spores (single set of chromosomes) |

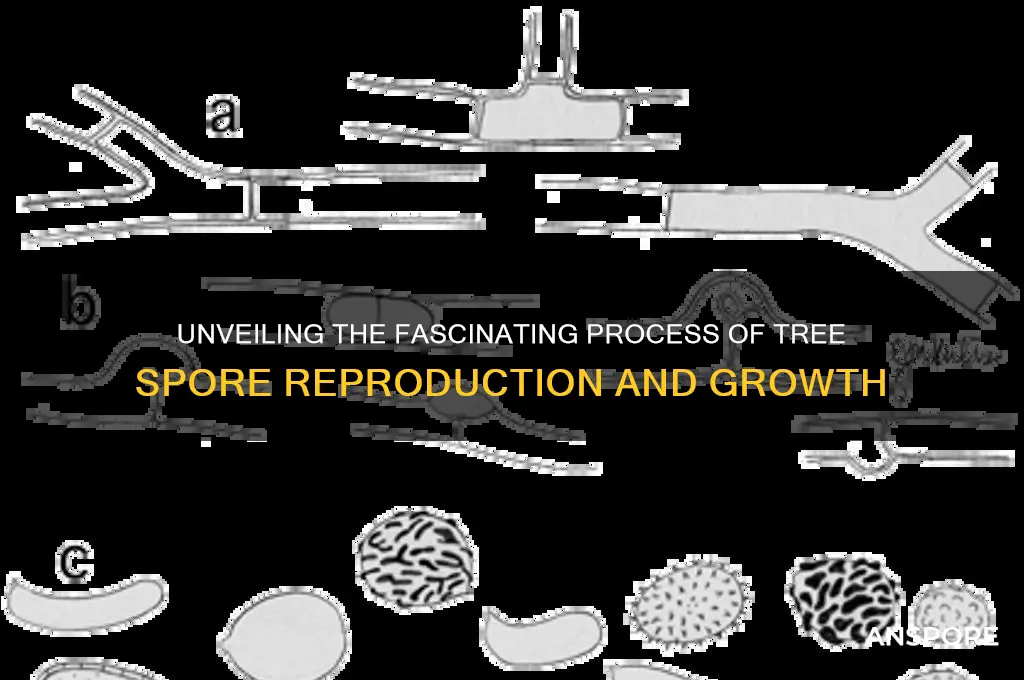

| Spore Types | Microspores (male) and megaspores (female) in seed plants; monolete or trilete spores in ferns |

| Spore Formation | Formed within sporangia, which are located on specialized structures like cones (in conifers) or undersides of fern fronds |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, or animals; spores are lightweight and often have adaptations (e.g., wings or floats) for dispersal |

| Germination | Spores germinate into gametophytes, which are small, photosynthetic plants |

| Fertilization | Occurs when sperm from the male gametophyte swims to the egg on the female gametophyte (requires water for sperm motility in ferns) |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations: sporophyte (tree) produces spores, which grow into gametophytes, which then produce the next sporophyte generation |

| Examples | Ferns reproduce via spores; some conifers like cycads produce spores in addition to seeds |

| Environmental Dependency | Spores require moist conditions for germination and fertilization, limiting spore-producing trees to specific habitats |

| Evolutionary Significance | Ancient method of reproduction, predating seeds; still prevalent in ferns and some primitive plants |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation in Trees: Trees like ferns produce spores in structures called sporangia on leaf undersides

- Wind Dispersal of Spores: Lightweight spores are carried by wind to new locations for germination

- Water Dispersal in Aquatic Trees: Spores of mangrove or water-adjacent trees are dispersed via water currents

- Germination Process of Spores: Spores land in suitable environments, absorb water, and grow into gametophytes

- Alternation of Generations: Trees alternate between spore-producing sporophyte and gamete-producing gametophyte phases

Spore Formation in Trees: Trees like ferns produce spores in structures called sporangia on leaf undersides

Trees like ferns have mastered the art of spore reproduction, a process that hinges on specialized structures called sporangia. These tiny, sac-like organs are strategically located on the undersides of fern leaves, or fronds, where they are protected yet accessible to air currents. Each sporangium houses hundreds of spores, which are essentially single-celled reproductive units. When mature, the sporangia dry out and rupture, releasing the spores into the wind. This dispersal mechanism ensures that ferns can colonize new areas efficiently, even in the absence of seeds or pollinators.

To understand spore formation, consider the lifecycle of a fern. Unlike trees that produce seeds, ferns alternate between a sporophyte (spore-producing) and gametophyte (gamete-producing) generation. The sporophyte, the familiar fern plant we see, develops sporangia on the undersides of its leaves. These sporangia undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores, which are then dispersed. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces gametes. Fertilization occurs when sperm from one gametophyte swims to an egg on another, eventually growing into a new sporophyte.

Practical observation of sporangia can be a rewarding activity for nature enthusiasts. To locate them, flip a fern frond and examine the underside with a magnifying glass. Look for clusters of brown or yellow dots, which are the sporangia. Gently tapping the frond over a piece of white paper can release the spores, allowing you to see their dust-like appearance. For educational purposes, collect spores by placing a mature frond in a paper bag for a few days, allowing the sporangia to dry and release their contents naturally.

While ferns are the most recognizable spore-producing plants, other tree-like species, such as cycads and some gymnosperms, also utilize spores in their reproductive cycles. However, ferns remain the quintessential example due to their widespread presence and visible sporangia. For gardeners or conservationists, understanding spore formation is crucial for propagating ferns or restoring habitats. Spores require moisture and shade to germinate, so creating a humid, shaded environment is key to successful cultivation.

In conclusion, spore formation in trees like ferns is a fascinating adaptation that relies on sporangia to produce and disperse reproductive units. By studying this process, we gain insights into plant evolution and practical techniques for propagation. Whether for scientific inquiry or gardening, observing sporangia on fern fronds offers a tangible connection to the intricate world of plant reproduction.

Do All Plants Form Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Wind Dispersal of Spores: Lightweight spores are carried by wind to new locations for germination

Trees and other spore-producing plants have mastered the art of wind dispersal, a strategy that ensures their survival and propagation across diverse environments. This method is particularly effective for species that produce lightweight spores, which can be carried over vast distances by even the gentlest breeze. For instance, ferns and certain fungi release spores that are so minuscule—often measuring just a few micrometers—that they can remain suspended in the air for hours, traveling miles before settling on a new substrate. This natural mechanism highlights the efficiency of wind as a dispersal agent, allowing plants to colonize areas far beyond their immediate surroundings.

Consider the process from a practical standpoint: wind dispersal is not merely a passive event but a finely tuned adaptation. Spores are often produced in vast quantities to increase the likelihood of successful germination. For example, a single fern frond can release thousands of spores in a single season. These spores are typically housed in structures like sporangia, which dry out and burst open, releasing their contents into the air. To maximize dispersal, plants often position these structures on elevated parts, such as the undersides of leaves or the tips of branches, where wind currents are strongest. Gardeners and conservationists can mimic this by planting spore-producing species in open, windy areas to encourage natural propagation.

From a comparative perspective, wind dispersal stands out as one of the most energy-efficient methods of reproduction in the plant kingdom. Unlike seed-producing plants, which invest energy in developing protective coats and nutrient stores, spore-producing plants allocate resources to sheer numbers and lightweight design. This strategy is particularly advantageous in unpredictable environments, where the ability to quickly colonize new areas can mean the difference between survival and extinction. For instance, after a forest fire, wind-dispersed spores can rapidly repopulate barren landscapes, outpacing competitors that rely on heavier seeds or animal dispersal.

To harness the power of wind dispersal in a controlled setting, such as a garden or reforestation project, there are specific steps to follow. First, select spore-producing species native to your region, as these are best adapted to local conditions. Second, ensure the planting site is exposed to consistent airflow, avoiding densely wooded or sheltered areas. Third, collect spores during their peak release period, typically in dry, windy weather, and scatter them evenly across the target area. Finally, maintain the site by minimizing disturbances, as spores require stable conditions to germinate successfully. By following these guidelines, you can replicate the natural process of wind dispersal and contribute to the proliferation of spore-producing plants.

In conclusion, wind dispersal of lightweight spores is a remarkable adaptation that showcases the ingenuity of nature. Its efficiency, scalability, and resilience make it a vital mechanism for plant reproduction, particularly in dynamic ecosystems. Whether you’re a gardener, conservationist, or simply an observer of the natural world, understanding this process can deepen your appreciation for the intricate ways plants ensure their survival and expansion. By applying this knowledge, you can actively participate in the propagation of these species, fostering biodiversity and ecological balance.

Can Mold Spores Penetrate Tape? Uncovering the Truth and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Water Dispersal in Aquatic Trees: Spores of mangrove or water-adjacent trees are dispersed via water currents

In the intricate dance of nature, water serves as both cradle and courier for the spores of aquatic trees, particularly mangroves and their water-adjacent counterparts. Unlike terrestrial trees that rely on wind or animals for spore dispersal, these water-loving species harness the relentless flow of currents to propagate their offspring. This strategy is not merely a coincidence but a finely tuned adaptation to their unique environment, where land and water intertwine. Mangrove spores, encased in buoyant structures, drift effortlessly with the tides, ensuring their journey to new habitats is both efficient and far-reaching.

Consider the mechanics of this process: mangrove propagules, often referred to as "viviparous seeds," are not true spores but function similarly in their dispersal role. These elongated, cigar-shaped structures detach from the parent tree while still alive, floating horizontally on the water’s surface. Their buoyancy is no accident—it’s a survival mechanism. As they travel, they can remain viable for weeks, even months, waiting for the right conditions to take root. Once they reach a suitable substrate, such as a mudflat or sandy shore, they orient themselves vertically, anchoring into the sediment and sprouting into a new tree. This method ensures that mangroves colonize vast stretches of coastline, forming dense, protective forests that shield inland ecosystems from storm surges and erosion.

The efficiency of water dispersal lies in its ability to transport spores over significant distances with minimal energy expenditure from the parent tree. For instance, studies have shown that mangrove propagules can travel up to 30 kilometers in favorable currents, a feat unmatched by wind or animal-mediated dispersal in similar environments. This long-distance dispersal is crucial for the survival of mangrove populations, especially in fragmented habitats where gene flow between isolated stands is essential for genetic diversity and resilience against environmental stressors.

However, this dispersal method is not without its challenges. Water currents are unpredictable, and spores may end up in unsuitable locations, such as open ocean waters where they cannot survive. Additionally, human activities like coastal development and pollution pose significant threats to this delicate process. For conservationists and ecologists, understanding these dynamics is key to protecting and restoring mangrove ecosystems. Practical tips for supporting natural dispersal include minimizing habitat disruption, creating protected corridors for water flow, and monitoring water quality to ensure spores have the best chance of reaching viable habitats.

In conclusion, water dispersal in aquatic trees is a testament to nature’s ingenuity, blending simplicity with sophistication. By leveraging the power of water currents, mangroves and similar species ensure their survival and expansion in challenging environments. For those seeking to preserve these vital ecosystems, the lesson is clear: protect the water, and you protect the future of these remarkable trees.

Pine Trees: Pollen Producers or Spores Carriers? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Process of Spores: Spores land in suitable environments, absorb water, and grow into gametophytes

Spores, the microscopic units of life, are nature's ingenious solution for plant reproduction, especially in trees like ferns and some conifers. These tiny, lightweight structures are designed to travel far and wide, seeking out environments where they can thrive. Once a spore lands in a suitable habitat—typically a moist, shaded area with access to nutrients—the germination process begins. This initial stage is critical, as it determines whether the spore will develop into a gametophyte, the next phase in the reproductive cycle.

The first step in germination is water absorption. Spores are incredibly resilient in their dormant state, but they require moisture to activate their metabolic processes. When a spore absorbs water, its protective outer layer softens, allowing enzymes to break down stored nutrients. This triggers cell division and growth. For optimal germination, the environment should maintain a consistent humidity level of at least 70%, with temperatures ranging between 20°C and 25°C. Too much water can lead to rot, while too little will halt the process entirely.

As the spore swells with water, it begins to develop into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure. This stage is crucial for sexual reproduction in spore-producing plants. The gametophyte produces gametes—sperm and eggs—which must unite to form a zygote. In ferns, for example, the gametophyte relies on a thin film of water for sperm to swim to the egg, emphasizing the importance of moisture throughout the process. Without this aquatic bridge, fertilization cannot occur, and the reproductive cycle stalls.

Practical tips for observing or facilitating this process include creating a controlled environment, such as a terrarium with a mix of peat moss and sand to mimic natural conditions. Mist the substrate regularly to maintain humidity, and ensure indirect light to prevent drying. For educational purposes, magnifying tools can help students observe the transformation from spore to gametophyte, offering a tangible connection to the intricate world of plant reproduction.

In summary, the germination of spores is a delicate yet fascinating process that hinges on environmental suitability and water availability. From absorption to gametophyte formation, each step is a testament to nature's precision. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation for plant biology but also equips us with the knowledge to cultivate and preserve these vital organisms.

Can Vinegar Effectively Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores? Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Alternation of Generations: Trees alternate between spore-producing sporophyte and gamete-producing gametophyte phases

Trees, like many plants, engage in a fascinating reproductive strategy known as alternation of generations. This process involves a cyclical shift between two distinct phases: the sporophyte and the gametophyte. The sporophyte phase, which is the dominant and more visible stage in trees, produces spores through specialized structures such as cones or flowers. These spores are not seeds but rather single-celled reproductive units that develop into the gametophyte phase. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, key traits for the survival of tree species across diverse ecosystems.

To understand this process, consider the life cycle of a pine tree. The mature pine (sporophyte) produces male and female cones. The male cones release pollen (microspores), while the female cones contain ovules. Pollination occurs when wind carries pollen to the ovules, initiating the development of seeds. However, before seeds form, the spores undergo a transformation into gametophytes. The male gametophyte is tiny and short-lived, producing sperm, while the female gametophyte remains within the ovule, nurturing the egg. This alternation between spore-producing and gamete-producing phases is a cornerstone of tree reproduction.

From a practical standpoint, understanding alternation of generations can aid in forestry management and conservation. For instance, knowing that spores are dispersed by wind helps in predicting seedling distribution and planning reforestation efforts. Additionally, recognizing the vulnerability of gametophytes to environmental stressors, such as drought or pollution, highlights the importance of protecting habitats during critical reproductive stages. For hobbyists or educators, observing this process in species like ferns or mosses, which exhibit more visible gametophytes, can provide a hands-on learning experience.

Comparatively, alternation of generations in trees differs from that in simpler plants like mosses or ferns. In mosses, the gametophyte phase is dominant, while in trees, the sporophyte phase takes precedence. This difference reflects evolutionary adaptations to varying environments. Trees, with their robust sporophytes, can invest more energy in growth and longevity, while their gametophytes remain diminutive and transient. This contrast underscores the versatility of alternation of generations as a reproductive strategy across the plant kingdom.

In conclusion, alternation of generations is a complex yet elegant mechanism that drives tree reproduction. By alternating between spore-producing sporophytes and gamete-producing gametophytes, trees ensure genetic diversity and resilience. Whether you're a forester, a botanist, or simply a nature enthusiast, appreciating this process deepens your understanding of how trees thrive and perpetuate their species. Practical applications, from conservation to education, further highlight the significance of this biological phenomenon in both natural and managed ecosystems.

Reviving Your Spore Creatures: Tips to Keep Playing and Evolving

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, only certain types of trees, such as ferns and some ancient tree-like plants like cycads, reproduce via spores. Most modern trees reproduce through seeds.

Spore-producing trees release spores from structures like sporangia, often located on the undersides of leaves or in cones. Wind or water carries the spores to new locations.

Spores are the first stage in the reproductive cycle of spore-producing trees. They develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes (sperm and eggs) to form a new plant.

No, spores and seeds are different. Spores are single-celled and require moisture to grow, while seeds are multicellular, contain stored food, and are more resilient to dry conditions.