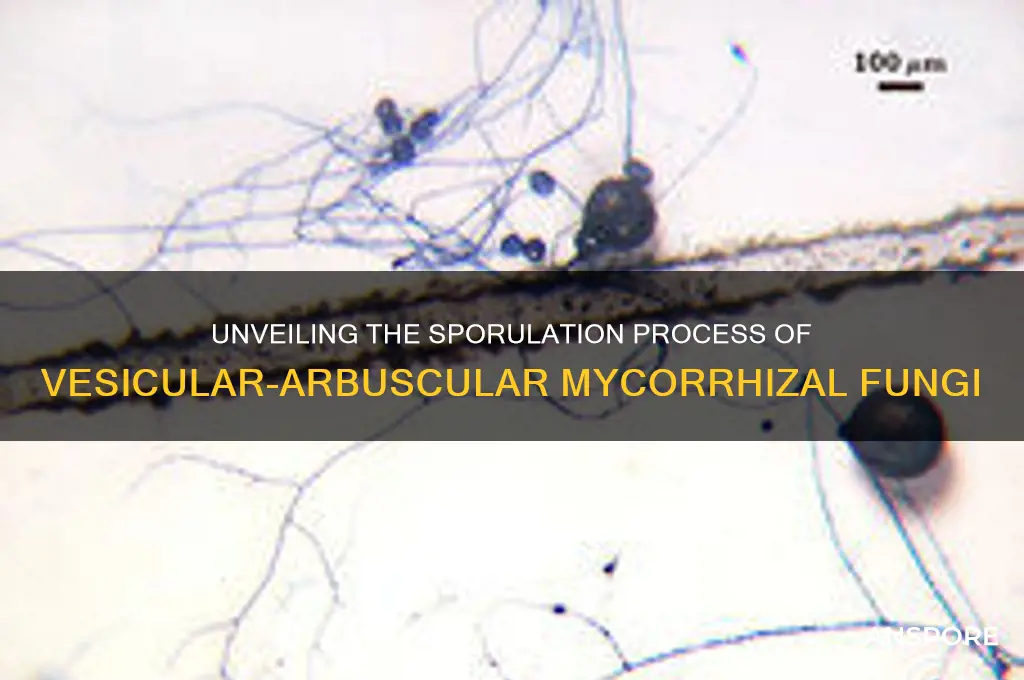

Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae (VAM), a type of symbiotic association between fungi and plant roots, produce spores as a crucial part of their life cycle. These spores, known as glomerospores, are formed within the soil and serve as a means of dispersal and survival for the fungus. The process begins when the fungus, belonging to the phylum Glomeromycota, colonizes the roots of a host plant, forming arbuscules and vesicles within the root cells. As the fungus matures, it develops hyphal networks that extend into the soil, where spore formation occurs. Spores are typically produced within specialized structures called sporocarps or directly on the hyphal tips, and their development is influenced by environmental factors such as nutrient availability, soil moisture, and host plant health. Once mature, the spores are released into the soil, where they can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions trigger germination, allowing the fungus to establish new mycorrhizal associations with compatible plant hosts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Spores | Asexual, chlamydospores |

| Location of Spore Formation | Within the soil or on root surfaces |

| Trigger for Spore Production | Environmental stress (e.g., nutrient scarcity, drought) or host signals |

| Structure Involved | Hyphal networks within the root cortex |

| Spore Wall Composition | Thick, multilayered, and resistant to degradation |

| Spore Size | Typically 10–100 μm in diameter |

| Spore Shape | Spherical or oval |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Soil water, root exudates, or soil fauna (e.g., earthworms) |

| Germination Process | Requires chemical signals from host roots (e.g., strigolactones) |

| Role of Spores | Survival structures for long-term persistence in soil |

| Host Dependency | Spores remain dormant until a suitable host plant is detected |

| Environmental Resistance | Tolerant to extreme conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, desiccation) |

| Lifespan | Can remain viable in soil for several years |

| Ecological Significance | Key for nutrient cycling and plant-fungal symbiosis in ecosystems |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Hyphal Growth and Differentiation: Hyphae extend, branch, and differentiate into spore-forming structures under nutrient-rich conditions

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like phosphorus availability, soil pH, and moisture levels influence spore production timing

- Sporocarp Development: Specialized structures called sporocarps form on hyphae, housing developing spores for protection

- Spore Maturation: Spores thicken their walls, accumulate nutrients, and become dormant for long-term survival

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are released via soil disturbance, water flow, or attachment to roots for colonization

Hyphal Growth and Differentiation: Hyphae extend, branch, and differentiate into spore-forming structures under nutrient-rich conditions

Under nutrient-rich conditions, hyphae of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae (VAM) undergo a remarkable transformation, shifting from vegetative growth to reproductive structures. This process begins with hyphal extension, where the fungus explores its environment in search of resources. As nutrients become abundant, particularly phosphorus and carbon, hyphae branch extensively, increasing their surface area to maximize absorption. This branching is not random but strategically directed toward nutrient hotspots, showcasing the fungus’s ability to sense and respond to environmental cues.

Differentiation follows extension and branching, marking the critical shift toward spore formation. Hyphae reallocate resources from growth to the development of specialized structures like sporocarps or spore-bearing hyphae. This transition is triggered by nutrient thresholds, with studies indicating that phosphorus levels above 50 ppm and carbon availability from host plants are key drivers. For example, in *Gigaspora margarita*, high phosphorus concentrations induce the formation of thick-walled spores within 2–3 weeks, ensuring survival in fluctuating environments.

The differentiation process is highly regulated, involving genetic and biochemical changes. Enzymes like chitin synthase and glycosyltransferases are upregulated to modify cell wall composition, creating the robust structures necessary for spore longevity. Simultaneously, lipid accumulation within spores provides energy reserves for germination. Practical applications of this knowledge include optimizing soil phosphorus levels (40–60 ppm) in agricultural settings to encourage spore production, enhancing mycorrhizal inoculants for crop systems.

Comparatively, VAM fungi differ from other mycorrhizal types, such as ectomycorrhizae, in their spore production mechanisms. While ectomycorrhizae often form fruiting bodies above ground, VAM spores develop internally within the soil matrix, relying on hyphal networks for dispersal. This distinction highlights the adaptability of VAM fungi to subterranean environments, where nutrient availability directly dictates reproductive success.

In conclusion, hyphal growth and differentiation in VAM fungi are finely tuned responses to nutrient-rich conditions, culminating in spore formation. By understanding this process, farmers and researchers can manipulate soil conditions to foster mycorrhizal activity, improving plant health and nutrient uptake. For instance, incorporating organic matter to maintain optimal phosphorus levels or using mycorrhizal inoculants during planting can enhance spore production, benefiting both natural and managed ecosystems.

Playing Spore on MacBook Air: Compatibility and Performance Guide

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Factors like phosphorus availability, soil pH, and moisture levels influence spore production timing

Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae (VAM), symbiotic fungi crucial for plant nutrient uptake, time their spore production in response to specific environmental cues. Among these, phosphorus availability stands out as a primary trigger. When soil phosphorus levels drop below 10-20 ppm, VAM fungi often increase spore production to ensure survival and dispersal. This response is adaptive: spores serve as a dormant, resilient life stage capable of enduring nutrient-poor conditions until more favorable environments arise. Farmers and gardeners can leverage this knowledge by monitoring soil phosphorus levels using standard soil tests and adjusting fertilization strategies to either encourage or suppress spore formation, depending on their goals.

Soil pH, another critical factor, significantly impacts VAM spore production. These fungi thrive in slightly acidic to neutral soils, with optimal pH ranges between 6.0 and 7.5. Outside this range, spore production declines sharply. For instance, in alkaline soils (pH > 8.0), VAM fungi may produce up to 50% fewer spores compared to optimal conditions. To counteract this, practitioners can amend soil pH using sulfur or lime, ensuring it remains within the ideal range. Regular pH testing, conducted biannually, is essential for maintaining conditions conducive to spore production and fungal health.

Moisture levels play a dual role in VAM spore production, balancing between necessity and excess. Adequate soil moisture, typically around 60-70% of field capacity, is required for fungal growth and spore development. However, waterlogging can suffocate the fungi, reducing spore output by as much as 30%. Conversely, drought conditions halt spore production entirely. Practical strategies include using drip irrigation to maintain consistent moisture levels and avoiding overwatering, particularly in heavy clay soils. Mulching can also help retain soil moisture while preventing waterlogging.

Comparing these environmental triggers reveals their interconnectedness. For example, low phosphorus availability and suboptimal pH can compound stress on VAM fungi, exacerbating reduced spore production. Similarly, moisture stress can amplify the negative effects of nutrient deficiencies. A holistic approach, addressing all three factors simultaneously, yields the best results. For instance, in a phosphorus-poor, acidic soil with erratic moisture, one might apply phosphate rock, sulfur to lower pH, and organic mulch to stabilize moisture—a trifecta of interventions that collectively enhance spore production.

Instructively, understanding these triggers allows for precise manipulation of VAM spore production in agricultural and ecological contexts. For reforestation projects, timing spore-rich inoculant applications to coincide with optimal phosphorus, pH, and moisture conditions can maximize fungal establishment. Similarly, in crop rotations, maintaining soil health through balanced fertilization, pH management, and moisture control ensures consistent VAM activity across seasons. By treating these environmental factors as levers, practitioners can harness the full potential of VAM fungi, fostering healthier plants and more resilient ecosystems.

Mold Spores and Brain Health: Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Sporocarp Development: Specialized structures called sporocarps form on hyphae, housing developing spores for protection

Sporocarps are the unsung heroes of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal (VAM) fungi, serving as protective nurseries for developing spores. These specialized structures emerge from the hyphae, the filamentous network that constitutes the fungus’s body, and act as a shield against environmental stressors. Unlike spores released directly into the soil, those housed within sporocarps benefit from a microenvironment optimized for maturation. This protective mechanism ensures higher spore viability, a critical factor in the fungi’s survival and dispersal strategies.

Consider the sporocarp as a biological incubator. Its development begins with the differentiation of hyphal cells, which thicken and aggregate to form a compact, resilient structure. Inside, spores develop in a controlled space, shielded from desiccation, predation, and chemical stressors. This process is particularly vital for VAM fungi, which rely on spores to colonize new plant roots and maintain their symbiotic relationships. Without sporocarps, spore production would be far less efficient, jeopardizing the fungi’s ability to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

To visualize sporocarp development, imagine a factory line within the fungal network. Hyphal cells receive signals—likely triggered by nutrient availability or environmental cues—to initiate sporocarp formation. These cells then undergo morphological changes, such as increased chitin deposition, to create a robust outer layer. Simultaneously, internal hyphae give rise to spore initials, which mature over time. The entire process is a testament to the fungi’s adaptability, as sporocarps can vary in size, shape, and structure depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Practical observations of sporocarp development can inform agricultural practices. For instance, farmers cultivating mycorrhizal-dependent crops like wheat or soybeans can enhance soil conditions to promote sporocarp formation. Ensuring adequate phosphorus levels, maintaining optimal soil pH (6.0–7.0), and minimizing soil disturbance are key steps. Additionally, incorporating organic matter can provide the carbon sources necessary for hyphal growth and sporocarp initiation. By fostering these structures, farmers can improve soil health and plant nutrient uptake, creating a more sustainable agroecosystem.

In conclusion, sporocarps are not merely passive containers but dynamic, purpose-built structures that underpin the reproductive success of VAM fungi. Their development is a finely tuned process, influenced by both internal and external factors, and their role in spore protection is indispensable. Understanding and supporting sporocarp formation offers tangible benefits, from enhancing crop yields to promoting ecological resilience. This specialized adaptation highlights the ingenuity of nature’s solutions, reminding us of the intricate relationships that sustain life beneath our feet.

Do Parts Influence Spore Growth? Exploring the Impact of Components

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Maturation: Spores thicken their walls, accumulate nutrients, and become dormant for long-term survival

Spores of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae (VAM) undergo a critical transformation during maturation, a process that ensures their long-term survival in diverse environments. This phase is marked by three key changes: thickening of the spore walls, accumulation of essential nutrients, and entry into dormancy. Each step is a strategic adaptation, allowing these spores to withstand harsh conditions and remain viable until favorable circumstances arise for germination.

Analytical Perspective: The thickening of spore walls is a defensive mechanism, akin to fortifying a fortress. Composed primarily of chitin and glucans, the cell wall becomes more resistant to desiccation, predation, and mechanical damage. Research indicates that mature VAM spores can endure extreme temperatures, ranging from -20°C to 50°C, and remain viable for decades. This resilience is crucial for their role in soil ecosystems, where they act as a reservoir of fungal inoculum, ready to colonize plant roots when conditions improve.

Instructive Approach: To understand nutrient accumulation, consider it as a survival kit preparation. During maturation, spores stockpile lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins, which serve as energy reserves. For instance, lipids can constitute up to 30% of the spore’s dry weight, providing a concentrated energy source. This internal nutrient storage is essential for the spore’s ability to germinate and form new mycorrhizal associations without immediate external resources. Practical applications of this knowledge include optimizing soil conditions to enhance spore viability, such as maintaining organic matter levels to support nutrient availability.

Comparative Insight: Dormancy in VAM spores shares similarities with seed dormancy in plants, yet it is uniquely tailored to fungal biology. Unlike seeds, which often require specific triggers like light or temperature changes to break dormancy, VAM spores respond primarily to root exudates from host plants. This specificity ensures that germination occurs only when a suitable host is present, maximizing the efficiency of energy use. Comparative studies highlight that while both seeds and spores employ dormancy as a survival strategy, the mechanisms and cues for activation differ significantly, reflecting their distinct ecological roles.

Descriptive Narrative: Imagine a spore in its mature state: a robust, nutrient-rich entity encased in a thick, protective shell, lying dormant in the soil. This dormant phase is not a passive state but a strategic pause, a waiting game for the right moment to spring into action. Over time, the spore’s internal clock ticks, monitoring environmental signals until the presence of a host plant triggers its awakening. This transformation from dormancy to active growth is a testament to the spore’s remarkable adaptability, ensuring the continuity of mycorrhizal networks across generations.

Persuasive Argument: Understanding spore maturation in VAM fungi is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications for agriculture and ecology. By manipulating soil conditions to favor spore maturation, farmers can enhance mycorrhizal colonization, improving nutrient uptake and plant health. For example, incorporating compost or reducing soil disturbance can promote spore viability. This knowledge empowers us to harness the natural processes of these fungi, fostering more sustainable and resilient agricultural systems. In essence, the maturation of VAM spores is a cornerstone of soil health, and its study offers actionable insights for both scientists and practitioners.

Buying Psychedelic Spores in Ireland: Legalities and Availability Explained

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are released via soil disturbance, water flow, or attachment to roots for colonization

Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae (VAM), a type of symbiotic fungus, rely on spore dispersal to colonize new root systems and expand their influence in ecosystems. Understanding how these spores are released and transported is crucial for optimizing soil health and agricultural practices. Among the primary mechanisms are soil disturbance, water flow, and root attachment, each playing a distinct role in ensuring the fungi’s survival and propagation.

Soil Disturbance: A Trigger for Release

Mechanical disruption of soil, whether through natural processes like burrowing animals or human activities such as tilling, exposes VAM spores buried within the substrate. This disturbance breaks apart soil aggregates, freeing spores that were previously encased. For instance, earthworms, while aerating soil, inadvertently carry spores on their bodies or through their castings, facilitating dispersal. Farmers can leverage this by minimizing excessive tilling, as over-disturbance may disrupt fungal networks, but strategic soil aeration can enhance spore availability for root colonization.

Water Flow: A Passive yet Effective Transport

Water acts as a passive carrier for VAM spores, particularly in agricultural and natural landscapes with sloping terrain or irrigation systems. Spores, being lightweight and often hydrophobic, can travel along water currents without sinking, eventually settling in new locations. In rice paddies, for example, floodwater redistributes spores across fields, promoting uniform mycorrhizal colonization. However, excessive runoff can lead to spore loss, so maintaining proper drainage and water management is essential to retain these beneficial fungi in the root zone.

Root Attachment: A Direct Path to Colonization

One of the most efficient dispersal mechanisms is the attachment of spores to plant roots, either directly or via soil particles adhering to root surfaces. When a host plant dies or sheds roots, attached spores are transported to new areas, ensuring continued colonization. This process is particularly effective in perennial crops, where root systems persist over multiple seasons. Gardeners and farmers can enhance this mechanism by planting cover crops with extensive root systems, which act as natural vectors for spore dispersal.

Practical Tips for Maximizing Dispersal

To optimize VAM spore dispersal, consider the following: incorporate organic matter to improve soil structure, reducing compaction and enhancing disturbance-driven release; design irrigation systems to mimic natural water flow patterns, avoiding erosion; and rotate crops with deep-rooted species to facilitate root-mediated dispersal. For example, planting legumes as cover crops not only fixes nitrogen but also aids in VAM propagation. By understanding and harnessing these mechanisms, practitioners can foster healthier, more resilient soils.

Archegoniophore's Role in Efficient Spore Dispersal: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae are symbiotic fungi belonging to the phylum Glomeromycota. They form mutualistic associations with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake. Their spores are crucial for survival, dispersal, and colonization of new host plants.

VAM fungi produce spores through asexual reproduction within the soil or inside root structures. Spores develop from hyphal swelling, often triggered by nutrient availability, host plant signals, or environmental conditions.

Spores can form either inside the plant root (intracellularly) or outside the root in the soil (extracellularly). Intracellular spores are produced within arbuscules or vesicles, while extracellular spores develop from soil hyphae.

Spore production is influenced by factors such as soil pH, nutrient availability (especially phosphorus), moisture levels, and the presence of a compatible host plant. Stress conditions, like nutrient deficiency, can also stimulate spore formation.

VAM spores are dispersed through soil movement, water runoff, and attachment to plant roots or soil particles. They can also be transported by animals, insects, or human activities, ensuring colonization of new habitats.