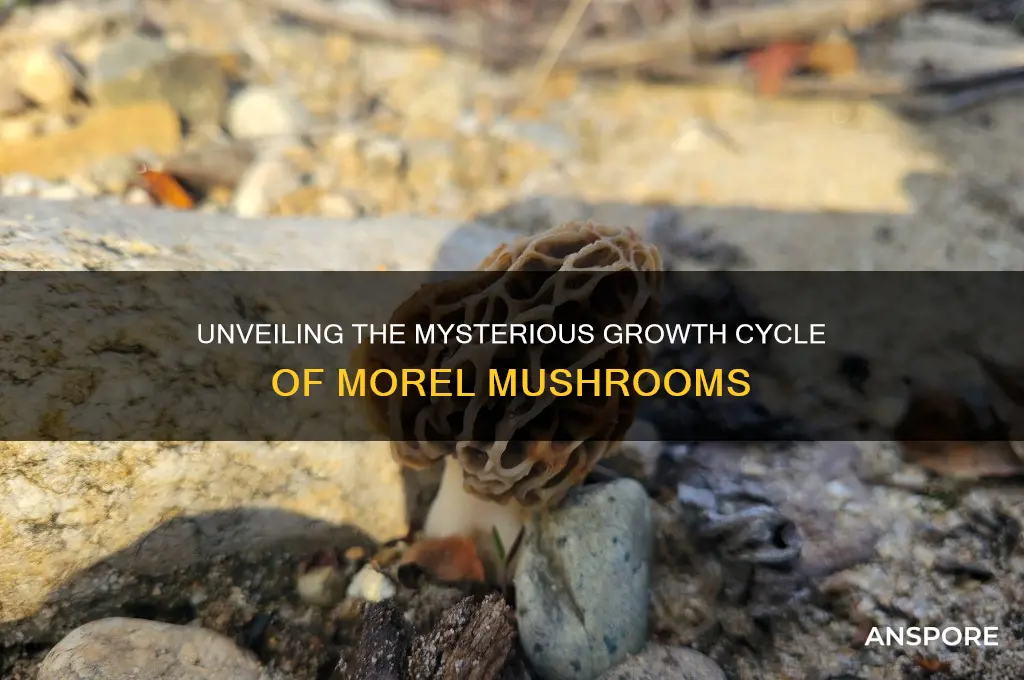

Morel mushrooms, prized for their unique honeycomb-like caps and rich, earthy flavor, grow under specific environmental conditions that support their symbiotic relationship with trees. These fungi thrive in temperate forests, particularly in areas with well-draining soil and ample organic matter, such as decaying leaves or wood. Morels typically emerge in spring, following periods of cool, moist weather, and require a balance of sunlight and shade. Their growth is closely tied to mycorrhizal associations, where the mushroom’s underground network of filaments, or mycelium, forms a mutually beneficial partnership with tree roots, exchanging nutrients for sugars. This delicate interplay between climate, soil, and host trees makes morel cultivation challenging, leaving foragers to rely on natural habitats to find these elusive and highly sought-after mushrooms.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore germination: Spores land on suitable soil, absorb moisture, and begin to grow mycelium

- Mycelium development: Underground network of threads expands, absorbing nutrients and preparing for fruiting

- Environmental triggers: Specific conditions like temperature, moisture, and soil pH signal fruiting body formation

- Fruiting body emergence: Morel caps and stems grow rapidly from the mycelium, breaking through the soil

- Maturation and spore release: Mature morels release spores, completing the life cycle and starting anew

Spore germination: Spores land on suitable soil, absorb moisture, and begin to grow mycelium

The journey of a morel mushroom begins with a microscopic marvel: the spore. These tiny, dust-like particles are the mushroom's equivalent of seeds, each containing the potential for new life. When spores are released into the environment, they embark on a quest for survival, seeking out the perfect conditions to initiate growth. This critical phase, known as spore germination, is a delicate process that sets the stage for the development of the iconic morel.

The Landing: Imagine a spore, carried by the wind or an insect, descending onto a forest floor. The first requirement for germination is a suitable substrate, typically rich, well-drained soil with a slightly acidic pH, often found in deciduous woodlands. This soil acts as a nurturing cradle, providing the necessary nutrients and structure for the spore to thrive. Upon landing, the spore's journey from a dormant state to an active one begins.

Moisture Activation: Water is the catalyst that awakens the spore. As it absorbs moisture from the surrounding environment, the spore's metabolic processes spring into action. This hydration triggers the breakdown of stored nutrients within the spore, providing the energy needed for growth. The spore swells, and a small germ tube emerges, marking the initial stage of mycelium development. This process is highly sensitive, requiring specific moisture levels; too little water, and the spore remains dormant; too much, and it may rot.

Mycelium Emergence: From the germ tube, a network of thread-like structures called mycelium begins to grow. This is the vegetative part of the fungus, akin to the roots of a plant. The mycelium spreads through the soil, secreting enzymes to break down organic matter and absorb nutrients. It is a voracious feeder, capable of growing several centimeters per day under optimal conditions. This stage is crucial, as the mycelium not only sustains the fungus but also forms a symbiotic relationship with trees, exchanging nutrients and enhancing soil health.

Environmental Factors: Spore germination is a precise art, influenced by various environmental cues. Temperature plays a pivotal role, with most morel species preferring a range of 50–70°F (10–21°C) for optimal growth. Light exposure, though not directly affecting germination, can impact the overall success of mycelium development. Additionally, the presence of specific bacteria and the absence of certain fungi can create a favorable environment for morel spores. Understanding these factors is essential for cultivators aiming to replicate the natural conditions that morels thrive in.

In the intricate world of morel mushrooms, spore germination is a pivotal moment, transforming a dormant spore into a thriving network of mycelium. This process, driven by the right combination of soil, moisture, and environmental cues, showcases the remarkable adaptability and resilience of these fungi. By comprehending these initial stages, enthusiasts and researchers alike can better appreciate the complexities of morel cultivation and the delicate balance required for their growth.

Chaga Mushroom: A Superfood with Amazing Benefits

You may want to see also

Mycelium development: Underground network of threads expands, absorbing nutrients and preparing for fruiting

Beneath the forest floor, a silent revolution unfolds as mycelium—the vegetative part of a fungus—expands its intricate network of threads, known as hyphae. This underground system is the lifeblood of the morel mushroom, a culinary delicacy prized for its earthy flavor and sponge-like texture. Mycelium development is a meticulous process, where each hyphal strand stretches outward, seeking organic matter to decompose and nutrients to absorb. This phase is critical, as it determines the mushroom’s future fruiting potential. Without a robust mycelial network, morels would never emerge above ground.

Imagine a spider web, but instead of catching prey, it captures and recycles nutrients from decaying wood, leaves, and soil. This is the mycelium’s role—a master recycler that breaks down complex organic materials into simpler compounds. As it grows, the mycelium secretes enzymes that dissolve nutrients, which are then absorbed directly into the hyphae. This process not only sustains the fungus but also enriches the soil, creating a symbiotic relationship with the surrounding ecosystem. For morels, this stage can last months or even years, depending on environmental conditions like temperature, moisture, and food availability.

To encourage mycelium development in a controlled setting, such as a garden or cultivated patch, specific conditions must be met. Maintain a soil pH between 6.0 and 7.5, and ensure the substrate—often a mix of wood chips, straw, or compost—remains consistently moist but not waterlogged. Temperatures between 50°F and 70°F (10°C and 21°C) are ideal for mycelial growth. Avoid overwatering, as excessive moisture can lead to anaerobic conditions that stifle development. Patience is key; mycelium growth is slow, but its success is non-negotiable for fruiting.

Comparing mycelium to the roots of a plant reveals both similarities and differences. While plant roots primarily anchor and absorb water, mycelium is a dynamic explorer, constantly seeking new resources and adapting to its environment. Its ability to form symbiotic relationships with trees (mycorrhiza) further distinguishes it, as morel mycelium often partners with specific tree species like ash, elm, or poplar. This partnership enhances nutrient exchange, benefiting both the fungus and the tree. Understanding this unique behavior is essential for anyone attempting to cultivate morels, as it underscores the importance of mimicking natural forest conditions.

In essence, mycelium development is the unsung hero of morel mushroom growth—a hidden, intricate process that lays the foundation for the prized fruiting bodies. By nurturing this underground network, whether in the wild or in cultivation, you’re not just growing mushrooms; you’re fostering a delicate balance between decomposition and regeneration. Practical tips, like using spore-inoculated substrate and monitoring environmental conditions, can significantly improve success rates. Master this stage, and you’ll unlock the secrets to a bountiful morel harvest.

Exploring Southeast Michigan's Forests: A Guide to Mushroom Hunting Adventures

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers: Specific conditions like temperature, moisture, and soil pH signal fruiting body formation

Morel mushrooms, those elusive and prized fungi, don’t emerge on a whim. Their fruiting bodies require a precise environmental symphony, where temperature, moisture, and soil pH play conductor. Imagine a thermostat set between 50°F and 60°F (10°C and 15°C) — this is the sweet spot for morel mycelium to awaken from dormancy. Below this range, growth stalls; above it, the energy shifts to spore production rather than fruiting. This narrow window explains why morels often appear in spring, when soil temperatures stabilize after winter’s chill but before summer’s heat.

Moisture is the next critical player, acting as both catalyst and caution. Morel mycelium thrives in soil with a moisture content of 50-70%, akin to a wrung-out sponge. Too dry, and the fungus conserves energy; too wet, and it risks rot or competition from other molds. Rainfall patterns, therefore, are a morel hunter’s best friend — a series of gentle rains followed by a few dry days often precedes a flush. Practical tip: Monitor local soil moisture using a soil moisture meter, aiming for the 50-70% range, and note that morels favor well-draining soils like sandy loam to avoid waterlogging.

Soil pH, often overlooked, is the silent influencer in this trio. Morels prefer slightly acidic to neutral soil, with a pH range of 6.0 to 7.5. Outside this range, nutrient availability shifts, and the mycelium struggles to absorb essential elements like phosphorus and potassium. For cultivators, testing soil pH with a kit and amending it with lime (to raise pH) or sulfur (to lower it) can create a morel-friendly environment. A pH of 6.5, for instance, mimics the conditions of ash-rich forests, a known morel hotspot.

The interplay of these factors is both delicate and dynamic. For instance, a sudden temperature drop after a warm spell can trigger fruiting, as can a brief drought followed by rain. This phenomenon, known as "shock fruiting," highlights the fungus’s adaptability to environmental stress. However, consistency is key for sustained growth. Fluctuations outside optimal ranges can halt fruiting or weaken the mycelium, underscoring why morels are more abundant in stable microclimates, such as woodland edges or burned areas where conditions align predictably.

Understanding these triggers isn’t just academic—it’s actionable. For foragers, tracking spring temperatures and rainfall patterns can predict morel seasons. For cultivators, creating controlled environments with precise temperature, moisture, and pH levels can coax fruiting bodies from mycelium. Whether in the wild or a garden bed, the lesson is clear: morels are not just found; they are summoned by the right environmental cues. Master these, and the forest’s most coveted mushroom may just reveal itself.

Safely Testing Mushrooms for Mold: A Comprehensive Guide for Growers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fruiting body emergence: Morel caps and stems grow rapidly from the mycelium, breaking through the soil

Morel mushrooms, those elusive and prized fungi, owe their dramatic appearance to a process as fascinating as it is swift. Beneath the soil, a network of mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—lies dormant, often for months or even years. When conditions align—typically in spring, with temperatures between 50°F and 70°F (10°C and 21°C) and adequate moisture—this hidden network springs into action. The mycelium, having absorbed nutrients from decaying organic matter, redirects its energy upward, initiating the rapid growth of the fruiting body. This is the moment when the morel’s iconic cap and stem emerge, breaking through the soil in a matter of days.

Consider the mechanics of this emergence. The mycelium, a delicate yet resilient structure, pushes through the soil with surprising force, driven by turgor pressure within its cells. This process is akin to a plant sprouting, but far more rapid. Within 24 to 48 hours, the morel’s stem elongates, and the cap begins to unfurl, revealing its honeycomb-like ridges. This speed is critical for the mushroom’s survival, as it must complete its life cycle before the soil dries or temperatures rise too high. For foragers, this means a narrow window of opportunity to harvest these delicacies before they sporulate and decay.

To witness this emergence firsthand, observe a patch of soil where morels have fruited previously. Mark the spot and monitor it daily during peak season. You’ll notice small bumps or cracks in the soil, signaling the mushroom’s ascent. Resist the urge to dig—disturbing the soil can damage the mycelium. Instead, wait patiently. By the next day, a fully formed morel may stand proudly, its cap and stem a testament to nature’s efficiency. This hands-off approach not only preserves the mycelium but also ensures future fruiting, as healthy networks can produce morels for years.

The rapid growth of morel fruiting bodies is a marvel of adaptation. Unlike cultivated mushrooms, which often grow in controlled environments, morels are wild and unpredictable. Their emergence depends on a delicate balance of factors: soil pH (ideally between 6.0 and 7.0), organic matter (such as decaying wood or leaves), and moisture. Even slight deviations can inhibit fruiting. For those attempting to cultivate morels, mimicking these conditions is key. Using a mix of hardwood chips and soil, maintaining consistent moisture, and providing shade can encourage mycelium to produce fruiting bodies. However, patience is paramount—morels may take a year or more to emerge, even under ideal conditions.

Finally, the emergence of morel caps and stems is a reminder of the fungus’s dual role: as a decomposer and a delicacy. As the fruiting body breaks through the soil, it begins its primary mission—releasing spores to propagate the species. For humans, this moment marks the culmination of a long wait, offering a fleeting chance to savor the mushroom’s earthy, nutty flavor. Whether you’re a forager, a cultivator, or simply an observer, the sight of a morel pushing through the earth is a spectacle that bridges the microscopic and the majestic, revealing the hidden wonders of the fungal world.

Do Genius Mushrooms Work? Unlocking Brain Power

You may want to see also

Maturation and spore release: Mature morels release spores, completing the life cycle and starting anew

Mature morels, with their honeycomb-like caps and earthy aroma, signal the culmination of a complex life cycle. This final stage is marked by spore release, a process both delicate and vital. As the mushroom’s tissues dry slightly, the asci (microscopic sacs within the cap’s pits) rupture, ejecting millions of spores into the air. This release is not random; it’s a precise, wind-dependent mechanism that ensures dispersal over a wide area. Each spore is a potential new beginning, carrying the genetic blueprint to colonize fresh substrates and perpetuate the species.

To observe this process, collect a mature morel and place it gill-side down on a piece of dark paper for 24 hours. The resulting spore print, a pattern unique to the species, reveals the mushroom’s reproductive effort. Foragers should note: handling mature morels gently preserves their spore-bearing structures, maximizing their contribution to future generations. This simple act of observation underscores the interconnectedness of fungal life cycles and the role humans play in their continuity.

From an ecological standpoint, spore release is a high-stakes event. Morel spores face numerous challenges—predation, desiccation, and competition—yet their sheer numbers increase the odds of success. Once airborne, spores settle on organic matter like decaying wood or soil rich in nutrients. Here, they germinate under optimal conditions (temperatures between 50–70°F and adequate moisture), forming a network of hyphae that will eventually fruit as new morels. This phase, known as mycelial colonization, can take months or even years, highlighting the patience embedded in the fungal life cycle.

Practical tips for fostering spore release include creating a humid environment for captive morels, such as placing them in a paper bag with a damp cloth. For those cultivating morels, introducing spore slurries (spores suspended in water) to prepared beds in early spring mimics natural dispersal. However, caution is advised: over-saturation can lead to mold, while insufficient moisture stalls germination. Balancing these factors requires attentiveness, akin to nurturing a fragile ecosystem.

Ultimately, maturation and spore release are not just biological processes but a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of morels. By understanding and supporting this stage, foragers, cultivators, and enthusiasts alike become stewards of a life cycle that has thrived for millennia. Each spore released is a promise of renewal, a reminder that even the most ephemeral organisms contribute to the enduring tapestry of life.

Spotting Tree Ear Mushrooms: A Beginner's Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Morel mushrooms thrive in specific conditions, including well-drained, moist soil with a pH between 6.0 and 7.0. They prefer temperate climates with temperatures ranging from 50°F to 70°F (10°C to 21°C) and require a balance of sunlight and shade. Morels often grow near deciduous trees like ash, elm, and oak, benefiting from the organic matter in the soil.

Morel mushrooms have a complex life cycle, and it can take anywhere from a few weeks to several years for them to grow from spores. Factors like soil conditions, temperature, and moisture play a significant role. Typically, morels fruit in spring, but the mycelium (the underground network of the fungus) can remain dormant for extended periods before producing mushrooms.

While morel mushrooms are primarily found in the wild, they can be cultivated under controlled conditions. Successful cultivation requires mimicking their natural habitat, including using specific soil mixes, maintaining proper moisture levels, and sometimes inoculating the soil with morel mycelium. However, cultivation is challenging and less predictable compared to wild foraging.