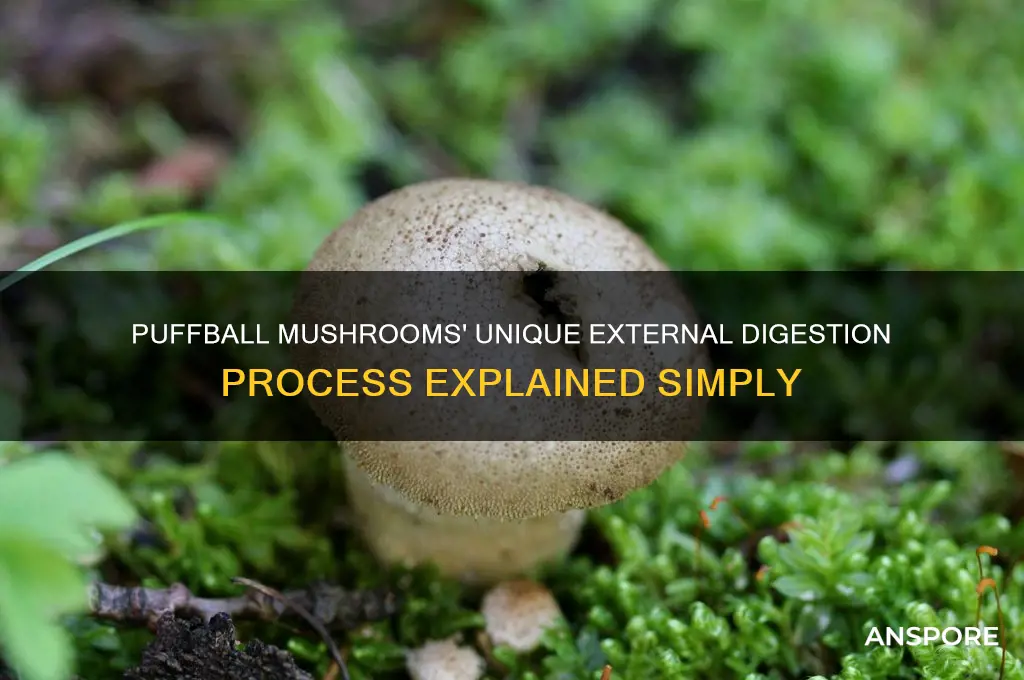

The puffball mushroom, a unique fungus, employs an intriguing method of external digestion to obtain nutrients. Unlike animals with internal digestive systems, puffballs secrete digestive enzymes directly onto their food source, typically decaying organic matter. These enzymes break down complex organic compounds into simpler substances that the mushroom can then absorb through its mycelium, a network of thread-like structures. This process, known as extracellular digestion, allows the puffball to efficiently extract nutrients from its environment, showcasing the remarkable adaptability of fungi in their quest for survival.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Digestion Type | External (extracellular digestion) |

| Process | Secrete digestive enzymes into the surrounding environment |

| Enzymes | Proteases, carbohydrases, and lipases |

| Substrates | Dead organic matter (e.g., wood, leaves, soil organic material) |

| Location of Digestion | Outside the fungal hyphae, in the substrate |

| Nutrient Absorption | Hyphae absorb the broken-down nutrients (e.g., amino acids, sugars, fatty acids) |

| Role of Mycelium | Produces and secretes enzymes; absorbs nutrients |

| Sporocarp Function | Produces and disperses spores; not directly involved in digestion |

| Environmental Impact | Decomposes organic matter, recycling nutrients in ecosystems |

| Efficiency | Highly efficient in breaking down complex organic materials |

| Ecological Role | Saprotrophic (decomposer) in nutrient cycling |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Enzyme release mechanisms

Puffball mushrooms, like many fungi, rely on external digestion to break down organic matter into absorbable nutrients. This process hinges on the strategic release of enzymes into their environment, a mechanism finely tuned by evolutionary pressures. Unlike animals, which internalize digestion, puffballs secrete enzymes directly onto their substrate, typically decaying wood or leaf litter. This extracellular approach maximizes nutrient extraction from complex materials like cellulose and lignin, which are otherwise indigestible by most organisms.

The enzyme release mechanism in puffballs is a multi-step process, beginning with the detection of suitable substrates. Hyphal tips, the exploratory filaments of the fungus, sense chemical cues from organic matter, triggering the production of enzymes within specialized cells. These enzymes, including cellulases, hemicellulases, and proteases, are packaged into vesicles and transported to the hyphal wall. Upon contact with the substrate, the hyphal membrane fuses with the vesicle, releasing the enzymes directly onto the target material. This targeted delivery ensures efficient use of metabolic resources, as enzymes are deployed only where they are most effective.

One critical aspect of this mechanism is the regulation of enzyme activity. Puffballs must balance the need for rapid nutrient acquisition with the energy cost of enzyme production. Environmental factors, such as pH, temperature, and moisture, influence enzyme stability and activity. For instance, cellulases in puffballs typically function optimally at neutral to slightly acidic pH levels (5.5–7.0) and temperatures between 25°C and 35°C. Deviations from these conditions can denature enzymes, rendering them inactive. Thus, puffballs often thrive in environments where these parameters are naturally maintained, such as forest floors with consistent humidity and moderate temperatures.

Practical applications of understanding puffball enzyme release mechanisms extend beyond mycology. Biotechnologists have harnessed these enzymes for industrial processes, such as biofuel production and textile manufacturing. For example, cellulases from fungi are used to break down plant biomass into fermentable sugars, a key step in ethanol production. To replicate optimal conditions, industrial processes often maintain reaction temperatures at 30°C and pH levels around 6.0, mirroring the natural environment of puffballs. This knowledge not only enhances efficiency but also reduces costs by minimizing enzyme degradation.

In conclusion, the enzyme release mechanism of puffball mushrooms exemplifies nature’s ingenuity in solving complex problems. By externalizing digestion and precisely regulating enzyme deployment, these fungi thrive in nutrient-poor environments. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, studying this process offers insights into fungal ecology and inspires innovations in biotechnology. Whether in the lab or the forest, the humble puffball serves as a reminder of the profound impact of microscopic mechanisms on macroscopic systems.

Unlocking Flavor: Creative Ways to Use Dried Porcini Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Substrate breakdown process

Puffball mushrooms, like many fungi, rely on external digestion to access nutrients from their environment. This process begins with the secretion of enzymes into the surrounding substrate, typically organic matter such as decaying wood, leaves, or soil. These enzymes break down complex organic compounds like cellulose, lignin, and proteins into simpler molecules that the fungus can absorb. Unlike animals, which internalize digestion, puffballs externalize this process, turning their environment into a nutrient-rich soup.

The substrate breakdown process is highly efficient and targeted. Puffball mushrooms produce a variety of enzymes, including cellulases, proteases, and lipases, each specialized for different components of the substrate. For example, cellulases target plant cell walls, while proteases degrade proteins. This enzymatic arsenal allows the fungus to extract maximum nutrients from its surroundings. The efficiency of this process is critical, as fungi lack the ability to move and must rely on their immediate environment for sustenance.

To optimize substrate breakdown, puffball mushrooms form an extensive network of hyphae, the thread-like structures that make up their body. These hyphae secrete enzymes and grow into the substrate, increasing the surface area for digestion and absorption. The hyphae also act as transport channels, moving nutrients back to the main fungal body. This dual function of hyphae—both digesting and transporting—ensures that the fungus can efficiently exploit its resources.

Practical observation of this process can be seen in the way puffballs colonize decaying logs or leaf litter. Over time, the substrate becomes softer and more degraded as the fungus breaks it down. Gardeners and foragers can encourage puffball growth by providing rich, organic substrates like compost or wood chips. However, caution should be taken to avoid disturbing established fungal colonies, as this can disrupt the delicate balance of the ecosystem.

In conclusion, the substrate breakdown process of puffball mushrooms is a remarkable example of nature’s ingenuity. By externalizing digestion and leveraging specialized enzymes, these fungi transform their environment into a source of nourishment. Understanding this process not only sheds light on fungal biology but also offers practical insights for gardening, conservation, and even biotechnology. Whether you’re a mycologist, gardener, or simply curious about the natural world, the efficiency of puffball digestion is a testament to the power of adaptation and resourcefulness.

Unlocking Turkey Tail Mushrooms' Benefits: Usage, Preparation, and Health Tips

You may want to see also

Nutrient absorption methods

Puffball mushrooms, like many fungi, rely on external digestion to break down organic matter into absorbable nutrients. This process begins with the secretion of enzymes from their hyphae—the thread-like structures that make up the mushroom’s mycelium. These enzymes are released directly into the surrounding environment, where they decompose complex compounds such as cellulose, lignin, and proteins into simpler molecules like sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids. This extracellular breakdown is essential because fungi lack a specialized digestive system, making external digestion their primary method of nutrient acquisition.

The efficiency of nutrient absorption in puffball mushrooms hinges on their ability to maximize surface area contact with the substrate. Hyphae grow extensively, forming a dense network that intertwines with the organic material they decompose. This intimate contact ensures that enzymes are in close proximity to their targets, accelerating the breakdown process. Once nutrients are liberated, they are absorbed directly through the cell walls of the hyphae via passive and active transport mechanisms. Passive transport relies on concentration gradients, while active transport requires energy to move nutrients against these gradients, ensuring even uptake in nutrient-poor environments.

A critical aspect of this process is the regulation of enzyme secretion based on the availability of resources. Puffball mushrooms are highly adaptive, adjusting their metabolic activity in response to the nutrient composition of their surroundings. For example, if nitrogen is scarce, they increase the production of proteases to break down proteins more efficiently. This adaptability allows them to thrive in diverse habitats, from forest floors to decaying wood. Gardeners and mycologists can mimic these conditions by providing organic substrates rich in cellulose and lignin, such as straw or wood chips, to encourage healthy mycelial growth.

Comparatively, the nutrient absorption methods of puffball mushrooms differ significantly from those of plants and animals. Unlike plants, which absorb nutrients directly through their roots via osmosis, fungi actively secrete enzymes to predigest their food externally. Similarly, animals ingest food and digest it internally, whereas fungi never internalize their substrate. This unique approach highlights the evolutionary specialization of fungi as decomposers, playing a vital role in nutrient cycling within ecosystems. Understanding these mechanisms can inform sustainable practices, such as using fungi for bioremediation or composting, where their external digestion capabilities are harnessed to break down organic waste efficiently.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to cultivation and conservation efforts. For instance, when growing puffball mushrooms, maintaining a pH range of 5.5 to 6.5 in the substrate optimizes enzyme activity, as fungal enzymes function best in slightly acidic conditions. Additionally, ensuring adequate moisture levels is crucial, as water is necessary for enzyme secretion and nutrient transport. Foraging enthusiasts should note that young, firm puffballs are ideal for consumption, while mature specimens release spores and lose their nutritional value. By appreciating the intricacies of nutrient absorption in puffball mushrooms, we can better utilize their ecological and culinary potential.

Does Mellow Mushroom Use Butter in Their Pizza Recipes?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$44.99 $80.99

Role of mycelium network

Puffball mushrooms, like many fungi, rely on external digestion to break down organic matter and absorb nutrients. This process is fundamentally supported by the mycelium network, a vast, intricate web of thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae secrete enzymes into the surrounding environment, decomposing complex materials such as cellulose and lignin into simpler compounds that the fungus can then absorb. Without this network, puffballs would lack the means to access the nutrients necessary for growth and reproduction.

Consider the mycelium as the puffball’s digestive system, but one that operates entirely outside its body. Unlike animals, which ingest food and digest it internally, puffballs extend their mycelium into substrates like soil or decaying wood. This external approach allows them to efficiently extract nutrients from environments where organic matter is abundant but not readily accessible. For instance, a single puffball’s mycelium can spread over several square meters, maximizing its nutrient-gathering potential.

To understand the mycelium’s role, imagine it as a highly efficient factory. The hyphae act as both workers and transport systems, secreting digestive enzymes and then absorbing the resulting nutrients. This process is particularly crucial for puffballs, which often grow in nutrient-poor environments. By leveraging the mycelium network, they can thrive in conditions where other organisms might struggle. For example, in a forest floor rich in fallen leaves and dead trees, the mycelium breaks down these materials, releasing nutrients that the puffball can use to develop its fruiting body.

Practical applications of this knowledge can be seen in gardening and agriculture. Incorporating mycelium-rich compost into soil enhances its fertility by accelerating the breakdown of organic matter. Gardeners can encourage puffball growth by maintaining moist, well-drained soil with ample organic debris, creating an ideal environment for mycelium expansion. Additionally, understanding the mycelium’s role highlights the importance of preserving fungal habitats, as these networks are vital for ecosystem health and nutrient cycling.

In conclusion, the mycelium network is the unsung hero of the puffball’s survival strategy. It enables external digestion, turning inaccessible resources into fuel for growth. By studying and supporting this network, we not only gain insights into fungal biology but also unlock practical ways to improve soil health and sustainability. Whether in a forest or a garden, the mycelium’s role is a testament to the ingenuity of nature’s designs.

Unlocking Lion's Mane Mushrooms: Benefits, Uses, and Easy Incorporation Tips

You may want to see also

Environmental factors impact

Puffball mushrooms, like many fungi, rely on external digestion to break down organic matter in their environment. This process is heavily influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and substrate composition. For instance, optimal temperatures for puffball enzymatic activity typically range between 15°C and 25°C (59°F to 77°F). Below 10°C (50°F), enzymatic activity slows significantly, while temperatures above 30°C (86°F) can denature the enzymes, halting digestion. Humidity levels are equally critical; puffballs thrive in environments with 70–90% relative humidity, as this ensures the substrate remains moist enough for enzymes to diffuse and act effectively.

Consider the substrate itself—the material on which puffballs grow. Decomposing wood, leaf litter, and soil rich in organic matter provide the nutrients puffballs need. However, the pH of the substrate plays a pivotal role. Puffballs prefer slightly acidic to neutral conditions, with a pH range of 5.5 to 7.0. Outside this range, enzyme efficiency drops, and nutrient uptake is compromised. For example, a substrate with a pH of 8.0 can reduce enzyme activity by up to 50%, severely limiting the mushroom’s ability to digest external materials.

Light exposure, though often overlooked, also impacts puffball digestion. While puffballs do not require light for photosynthesis, indirect light can influence the temperature and humidity of their environment. Direct sunlight can dry out the substrate, reducing moisture levels below the 70% threshold needed for enzymatic activity. Conversely, consistent shade can maintain optimal humidity but may lower temperatures, slowing digestion. Gardeners cultivating puffballs should aim for dappled light conditions, mimicking the forest floor where these fungi naturally thrive.

Airflow is another environmental factor that affects puffball digestion. Adequate ventilation ensures a steady supply of oxygen, which is essential for the metabolic processes driving enzyme production. Stagnant air can lead to anaerobic conditions, inhibiting fungal growth and digestion. However, excessive airflow can desiccate the substrate, disrupting the moisture balance. A practical tip for growers is to use a small fan set on low to create gentle airflow, maintaining oxygen levels without drying out the environment.

Finally, pollution and chemical exposure can disrupt puffball digestion. Pesticides, herbicides, and heavy metals in the soil can inhibit enzymatic activity or even kill the fungus. For example, copper sulfate, a common fungicide, is toxic to puffballs at concentrations above 50 ppm. Growers should test soil for contaminants and opt for organic substrates to ensure a clean environment. By controlling these environmental factors, one can optimize conditions for puffball mushrooms to efficiently use external digestion, whether in a natural setting or a cultivated environment.

Maximizing Mushroom Benefits: Should You Use the Whole Mushroom?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

External digestion is a process where organisms break down food outside their bodies before absorbing the nutrients. Puffball mushrooms, like many fungi, secrete digestive enzymes into their environment to decompose organic matter. These enzymes break down complex molecules into simpler forms that the mushroom can then absorb through its mycelium.

Puffball mushrooms release digestive enzymes through their hyphae, which are thread-like structures that make up the mycelium. The hyphae grow into the substrate (such as soil or decaying matter) and secrete enzymes that break down nutrients. This process allows the mushroom to access and absorb essential compounds like sugars, amino acids, and minerals.

Puffball mushrooms, being fungi, lack a digestive system like animals. Instead, they absorb nutrients directly through their cell walls. External digestion is more efficient for fungi because it allows them to break down large, complex materials in their environment into smaller, absorbable molecules. This adaptation enables puffball mushrooms to thrive in nutrient-poor environments by extracting resources from decaying organic matter.