Spores are a remarkable reproductive strategy employed by various organisms, including fungi, plants, and some bacteria, to ensure survival and dispersal in challenging environments. Unlike seeds, spores are typically single-celled and lack the stored nutrients found in plant seeds. They reproduce through a process called sporulation, where a parent organism produces spores either asexually (mitospores) or sexually (meiospores). Asexual spores, such as conidia in fungi, are formed through mitosis and serve as a rapid means of reproduction and dispersal. Sexual spores, like zygospores or ascospores, result from the fusion of gametes and genetic recombination, increasing genetic diversity. Once released, spores can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate and grow into new individuals. This resilience allows spores to colonize diverse habitats, making them a highly effective mechanism for survival and propagation in the natural world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Asexual (primarily) |

| Process | Sporulation (formation of spores within a sporangium) |

| Spore Types | Endospores (bacterial), Conidia (fungal), Spores (plant) |

| Formation | Produced inside a sporangium (spore case) or directly on specialized structures |

| Dispersal | Wind, water, animals, or mechanical means |

| Germination | Spores remain dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination |

| Survival | Highly resistant to harsh environments (heat, desiccation, chemicals) |

| Genetic Variation | Limited in asexual spores; some fungi produce sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) |

| Examples | Bacteria (endospores), Fungi (conidia, zygospores), Plants (fern spores, pollen) |

| Ecological Role | Dispersal, survival in adverse conditions, colonization of new habitats |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Germination Process: Activation and emergence of a new organism from a dormant spore

- Asexual Spore Reproduction: Single-parent spores divide to produce genetically identical offspring

- Sexual Spore Formation: Fusion of gametes creates spores with genetic diversity

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like moisture, light, and temperature initiate spore reproduction

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, or animals spread spores to new habitats for growth

Spore Germination Process: Activation and emergence of a new organism from a dormant spore

Spores, often likened to nature's survival capsules, remain dormant until conditions trigger their awakening. This activation marks the beginning of spore germination, a process that transforms a dormant, resilient structure into a metabolically active organism. The first step involves the absorption of water, a critical factor that rehydrates the spore and initiates metabolic activity. For example, in *Bacillus subtilis*, a soil bacterium, spores can remain viable for decades, only to spring to life when moisture levels rise above 90% relative humidity. This hydration phase is not merely about water intake; it’s a precise biochemical event that reactivates enzymes and DNA repair mechanisms, preparing the spore for the next stage.

Once hydrated, the spore’s protective coat begins to weaken, allowing nutrients to enter and waste products to exit. This exchange is essential for energy production and growth. In fungi like *Aspergillus*, germination is further stimulated by specific nutrients such as glucose or ammonium ions, which act as signals for the spore to proceed with development. Temperature also plays a pivotal role; most bacterial spores germinate optimally between 25°C and 37°C, while fungal spores may require cooler conditions, around 20°C to 25°C. These environmental cues ensure that germination occurs only when conditions are favorable for survival and proliferation.

The emergence of a new organism from the spore is a carefully orchestrated process. In bacteria, the spore’s cortex, a thick layer of peptidoglycan, is degraded by enzymes like cortex-lytic enzymes (CLEs), allowing the core to expand. This expansion is followed by the outgrowth phase, where the spore develops into a vegetative cell. For fungi, the process involves the formation of a germ tube, a filamentous structure that extends from the spore and eventually develops into hyphae. This stage is particularly vulnerable, as the emerging organism lacks the spore’s protective layers, making it susceptible to environmental stressors.

Practical applications of spore germination are vast, from food preservation to biotechnology. For instance, controlling germination in *Clostridium botulinum* spores is crucial in the food industry to prevent botulism, often achieved by maintaining low water activity (below 0.92) and refrigeration (below 4°C). Conversely, in agriculture, promoting spore germination in beneficial fungi like *Trichoderma* can enhance soil health and plant growth. Understanding the germination process allows for targeted interventions, whether to inhibit harmful spores or activate beneficial ones.

In conclusion, spore germination is a remarkable transformation from dormancy to life, driven by precise environmental and biochemical cues. By manipulating these factors, we can harness the power of spores for various applications, from ensuring food safety to improving agricultural productivity. This process underscores the adaptability and resilience of life, encapsulated in the tiny, yet mighty, spore.

Stinkhorn Fungus Spores: Unveiling Their Unique Dispersal Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Asexual Spore Reproduction: Single-parent spores divide to produce genetically identical offspring

Spores, the resilient survival units of certain plants, fungi, and microorganisms, employ a remarkable strategy for reproduction: asexual division. Unlike sexual reproduction, which requires two parents and results in genetic diversity, asexual spore reproduction is a solo act. A single spore, acting as both parent and progenitor, divides to create offspring that are genetically identical to itself. This process, known as mitosis, ensures that each new spore carries the exact same DNA as its parent, a clone in every sense.

Consider the fungus *Penicillium*, the mold behind penicillin. When conditions are right, a single *Penicillium* spore germinates and grows into a mycelium, a network of thread-like structures. As resources become scarce or environmental stress increases, the mycelium produces structures called conidiophores. At the tips of these structures, chains of spores (conidia) form through mitotic division. Each conidium is a miniature replica of the original spore, ready to disperse and repeat the cycle. This efficiency allows *Penicillium* to colonize new environments rapidly, a trait exploited in industrial antibiotic production.

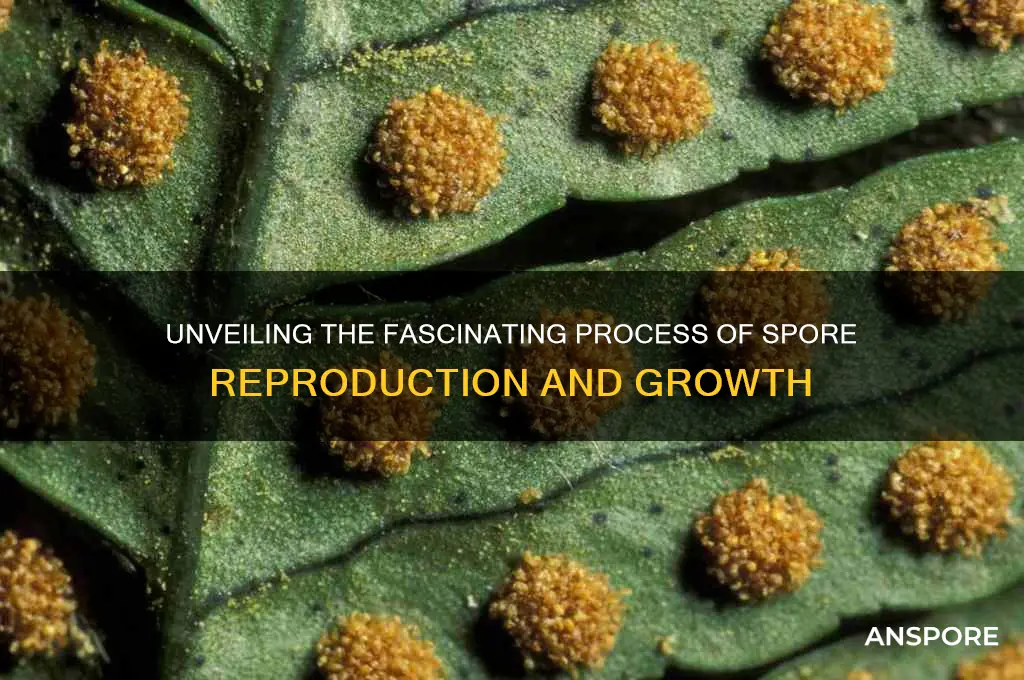

The advantages of asexual spore reproduction are clear: speed, simplicity, and consistency. For organisms like ferns, which produce dust-like spores called sporophytes, this method ensures rapid colonization of favorable habitats. A single fern frond can release thousands of spores, each capable of growing into a new plant under the right conditions. However, this strategy comes with a trade-off. Genetic uniformity means that if a disease or environmental change threatens one individual, it threatens all. Diversity, the hallmark of sexual reproduction, is sacrificed for the sake of proliferation.

Practical applications of this process extend beyond nature. In agriculture, understanding asexual spore reproduction helps in managing fungal pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea*, which causes gray mold in crops. By disrupting spore production or dispersal, farmers can limit the spread of this genetically uniform pest. Similarly, in biotechnology, asexual spores are used to produce consistent strains of microorganisms for fermentation processes, such as brewing or baking. For instance, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, the yeast used in bread and beer, reproduces asexually through budding, ensuring that each cell produces identical offspring for reliable results.

In conclusion, asexual spore reproduction is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. By forgoing genetic recombination, single-parent spores prioritize efficiency and consistency, traits that have proven invaluable in both ecological and industrial contexts. Whether in the forest floor or the laboratory, this process underscores the adaptability of life, even when working with a single genetic blueprint.

Exploring Spore's Multiplayer Mode: Cooperative Gameplay and Online Features

You may want to see also

Sexual Spore Formation: Fusion of gametes creates spores with genetic diversity

Spores, often associated with plants and fungi, are not merely dormant survival structures but also agents of genetic innovation. In the realm of sexual spore formation, the fusion of gametes—specialized reproductive cells—triggers a process that generates spores with unique genetic combinations. This mechanism is pivotal for species evolution, ensuring adaptability to changing environments through increased genetic diversity. Unlike asexual reproduction, which clones existing genetic material, sexual spore formation introduces variability by combining genetic contributions from two parents.

Consider the lifecycle of ferns, a classic example of sexual spore formation. Ferns produce two types of spores: macrospores (female) and microspores (male). When conditions are favorable, these spores germinate into gametophytes, which then release egg and sperm cells. The fusion of these gametes results in a zygote, which develops into a new fern plant. This process, known as alternation of generations, highlights how sexual reproduction in spore-forming organisms fosters genetic recombination. Each new spore carries a distinct genetic blueprint, enhancing the species’ resilience against diseases and environmental stressors.

To illustrate the practical implications, imagine a fungal species facing a new pathogen. Asexual spores, being genetically identical to their parent, would all succumb to the disease. However, sexually formed spores, with their diverse genetic makeup, increase the likelihood that some individuals will possess resistance traits. This survival advantage underscores the evolutionary significance of sexual spore formation. For gardeners or farmers combating fungal infections, understanding this process can inform strategies like crop rotation or introducing resistant varieties to mitigate losses.

From a comparative perspective, sexual spore formation shares similarities with animal and human reproduction but operates on a microscopic scale. Just as sexual intercourse in humans combines genetic material from two parents, the fusion of fungal or plant gametes achieves the same end. However, spores’ ability to remain dormant for extended periods—sometimes centuries—adds a layer of complexity. This dormancy, coupled with genetic diversity, ensures that spore-forming organisms can endure harsh conditions and recolonize when environments become favorable.

Incorporating this knowledge into practical applications, researchers and conservationists can leverage sexual spore formation to preserve endangered species. By cultivating conditions that encourage sexual reproduction in spore-forming plants or fungi, they can enhance genetic diversity within populations. For instance, in reforestation efforts, planting ferns or mosses from diverse genetic sources can improve ecosystem resilience. Similarly, in agriculture, promoting sexual spore formation in beneficial fungi can lead to more robust soil health and crop yields. This approach not only safeguards biodiversity but also ensures the long-term sustainability of ecosystems and food systems.

Does Wet Black Mold Release Spores? Understanding the Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

Environmental Triggers: Factors like moisture, light, and temperature initiate spore reproduction

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi, plants, and some bacteria, lie dormant until environmental cues awaken their reproductive potential. Among these triggers, moisture, light, and temperature play pivotal roles in signaling the optimal conditions for germination and growth. For instance, many fungal spores require a specific humidity level—typically above 90%—to initiate metabolic activity. This moisture acts as a catalyst, softening the spore’s protective wall and allowing water uptake, a critical first step in reproduction. Without sufficient moisture, spores remain in stasis, their genetic material preserved but inactive.

Light, often overlooked, serves as another critical environmental trigger for spore reproduction. Certain plant spores, such as those of ferns, are photodormant, meaning they require exposure to specific wavelengths of light to break dormancy. Blue light, in particular, has been shown to stimulate germination in species like *Ceratopteris richardii*, with studies indicating that exposure to 450 nm light for as little as 15 minutes can significantly increase germination rates. This light-dependent mechanism ensures spores activate only when they reach a surface conducive to growth, such as a forest floor with filtered sunlight.

Temperature acts as a fine-tuned regulator, dictating whether spores remain dormant or spring to life. For example, *Aspergillus* spores germinate optimally between 25°C and 37°C, while temperatures below 10°C or above 45°C inhibit growth. This temperature sensitivity is not arbitrary; it reflects the organism’s evolutionary adaptation to its native environment. In practical terms, controlling temperature is a key strategy in food preservation, as chilling stored produce below 4°C can prevent fungal spore germination and extend shelf life.

The interplay of these environmental triggers—moisture, light, and temperature—creates a precise ecological niche for spore reproduction. For gardeners, understanding these factors can inform strategies like seed starting: maintaining a humid environment (e.g., using a dome or misting), providing adequate light (fluorescent bulbs placed 6 inches above seedlings), and keeping temperatures consistent (using heating mats for tropical species). Similarly, in industrial settings, manipulating these variables can control microbial growth in food processing or pharmaceutical manufacturing.

In essence, environmental triggers act as nature’s alarm clock for spores, synchronizing their awakening with conditions that maximize survival. By harnessing this knowledge, humans can either foster or inhibit spore reproduction, depending on the context. Whether cultivating beneficial fungi or preventing spoilage, the key lies in mastering the delicate balance of moisture, light, and temperature—a testament to the elegance of biological design.

Mold Spores and Pain: Uncovering the Hidden Health Risks

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, or animals spread spores to new habitats for growth

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi, plants, and some bacteria, rely on dispersal mechanisms to reach new habitats where they can germinate and grow. Among the most effective methods are wind, water, and animals, each playing a unique role in spreading spores across diverse environments. Wind, for instance, acts as a passive yet powerful agent, carrying lightweight spores over vast distances. This mechanism is particularly crucial for fungi like *Puccinia* (rust fungi) and plants such as ferns, whose spores are designed to float effortlessly on air currents. The efficiency of wind dispersal is evident in the global distribution of species like *Aspergillus*, whose spores can travel thousands of kilometers.

Water, another key disperser, is especially vital for aquatic and semi-aquatic organisms. Spores of algae, such as *Chlamydomonas*, and certain fungi, like *Blastocladiella*, are adapted to float or sink in water, ensuring they reach suitable substrates. For example, the spores of *Pilobolus*, a fungus commonly found on herbivanimal dung, use water droplets as a launchpad, ejecting spores with precision to land on nearby vegetation. This targeted dispersal increases the likelihood of encountering a new host or nutrient-rich environment. When utilizing water for spore dispersal, it’s essential to consider the spore’s buoyancy and the water flow’s velocity, as these factors determine the distance and direction of travel.

Animals, both large and small, serve as unintentional carriers of spores, facilitating their spread through movement and behavior. Endozoochory, where spores pass through an animal’s digestive system, is common in fungi like *Coprinus* and certain plant species. For instance, birds and mammals ingest spore-laden fruits or fungi, excreting the spores in new locations. Epizoochory, where spores attach to an animal’s fur or feathers, is another effective method. The burdock plant’s hook-like seeds, which inspired Velcro, demonstrate this mechanism’s efficiency. To maximize animal-mediated dispersal, spores often evolve adhesive or hook-like structures, ensuring they remain attached during transport.

Comparing these mechanisms reveals their complementary roles in spore dispersal. Wind offers broad, indiscriminate reach, while water provides targeted movement within specific ecosystems. Animals, however, combine mobility with the ability to access otherwise inaccessible areas, such as tree canopies or underground burrows. Each mechanism has evolved to suit the spore’s ecological niche, ensuring survival and proliferation in diverse environments. For practical applications, such as in agriculture or conservation, understanding these mechanisms can inform strategies for controlling unwanted fungal growth or promoting beneficial species.

In conclusion, the dispersal of spores through wind, water, and animals is a testament to nature’s ingenuity in ensuring species survival. By leveraging these mechanisms, spores overcome the limitations of their microscopic size, colonizing new habitats and maintaining ecological balance. Whether you’re a gardener combating fungal pathogens or a researcher studying plant ecology, recognizing the role of these dispersal agents can provide valuable insights and actionable strategies. For instance, reducing standing water can limit fungal spore spread, while planting animal-attracting species can enhance beneficial spore dispersal in natural areas.

Exploring Varied Growth Patterns of Different Types of Spores

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A spore reproduces asexually through a process called sporulation, where it germinates under favorable conditions, grows into a new individual organism, and eventually produces more spores.

Spores are triggered to reproduce when environmental conditions become favorable, such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability, which signal the spore to germinate and initiate growth.

Spores themselves reproduce asexually, but in some organisms (like fungi and ferns), spores develop into gametophytes that can undergo sexual reproduction to form new sporophytes, completing the life cycle.