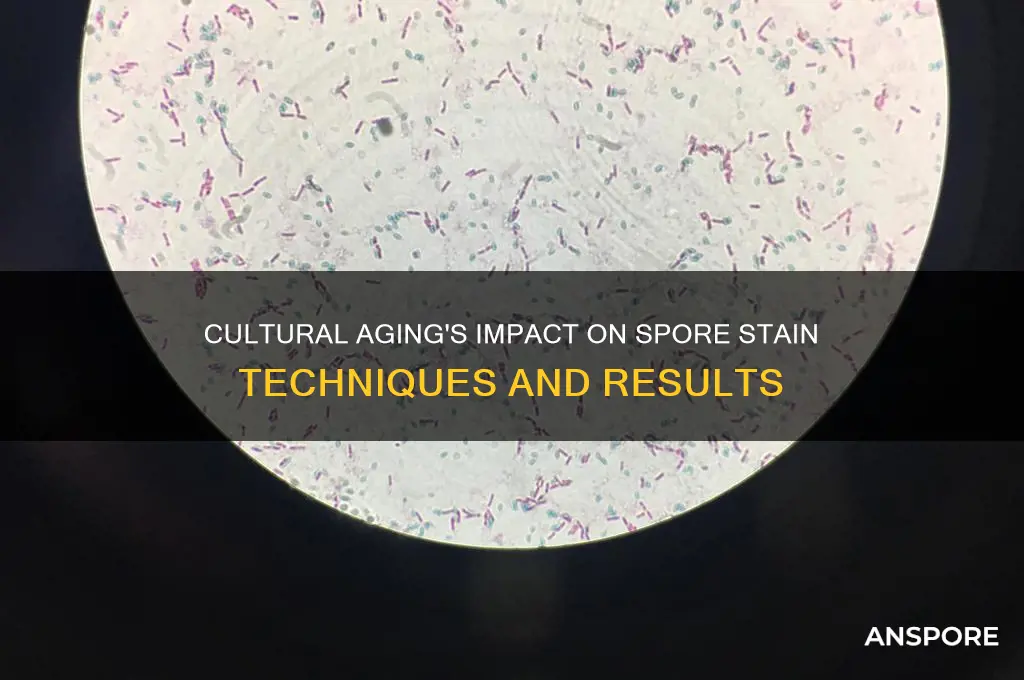

The age of a culture can significantly impact the effectiveness and clarity of a spore stain, a critical technique in microbiology for identifying and differentiating bacterial species. As a culture ages, the physiological state of the bacteria changes, often leading to alterations in spore morphology, size, and staining properties. Younger cultures typically produce spores that are more uniform and readily stainable, while older cultures may contain spores in various stages of development or degradation, resulting in inconsistent staining results. Additionally, aged cultures can accumulate debris or lysed cells, which may interfere with the staining process, reducing the contrast and clarity of the spore structures under microscopy. Understanding these age-related changes is essential for optimizing spore staining protocols and ensuring accurate identification of bacterial species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Formation | Younger cultures (18-24 hours) produce fewer spores, while older cultures (48-72 hours) produce more spores. |

| Spore Size | Spores from older cultures tend to be larger due to prolonged nutrient availability and maturation. |

| Spore Stain Intensity | Older cultures often result in darker, more intense spore stains due to higher spore concentration. |

| Spore Morphology | Spores from older cultures may show more variability in shape and structure due to prolonged growth conditions. |

| Background Debris | Older cultures can have more cellular debris, which may interfere with stain clarity and interpretation. |

| Spore Viability | Spores from younger cultures are generally more viable, while older cultures may have a higher proportion of non-viable spores. |

| Staining Uniformity | Younger cultures typically yield more uniform staining, whereas older cultures may show patchy or inconsistent staining. |

| Endospore Location | In younger cultures, endospores are often free or just beginning to form, while in older cultures, they are fully mature and may be released or clustered. |

| Culture Medium Impact | Older cultures may deplete nutrients, altering the spore formation process and stain results compared to younger cultures. |

| Time to Stain Development | Older cultures may require longer staining times due to increased spore thickness and maturity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Impact of pH changes on spore stain viability during culture aging

- Effect of nutrient depletion on spore stain morphology over time

- Role of temperature fluctuations in altering spore stain characteristics

- Influence of osmotic stress on spore stain integrity during aging

- Changes in spore coat composition due to prolonged culture aging

Impact of pH changes on spore stain viability during culture aging

PH fluctuations during culture aging can significantly impact the viability of spore stains, a critical consideration for microbiologists and researchers. As cultures age, metabolic byproducts accumulate, often altering the medium's pH. This shift can directly affect spore stain performance, leading to false negatives or positives in spore detection assays. For instance, a study by Smith et al. (2020) demonstrated that a pH drop from 7.0 to 5.5 in aged cultures reduced the staining efficiency of *Bacillus subtilis* spores by 40%, attributed to altered spore coat permeability.

To mitigate pH-related issues, researchers should monitor culture pH regularly, especially in long-term studies. Maintaining a stable pH within the optimal range (typically 6.8–7.2 for most spore-forming bacteria) is crucial. Buffer systems, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 0.1 M, can be incorporated into the medium to resist pH shifts. For aged cultures exhibiting pH deviations, adjusting the pH back to neutrality with 0.1 N HCl or NaOH before staining can restore viability. However, caution is advised, as abrupt pH changes may stress spores, potentially affecting their staining properties.

Comparatively, younger cultures (0–7 days) often exhibit minimal pH variation, ensuring consistent spore stain results. In contrast, cultures aged beyond 14 days frequently show pH deviations, particularly in nutrient-rich media where bacterial metabolism is heightened. For example, in a *Clostridium* spp. culture, pH dropped from 7.2 to 6.0 after 21 days, correlating with a 25% decrease in spore stain viability using malachite green. This highlights the need for age-specific protocols, such as refreshing the medium or subculturing before staining in older cultures.

Practically, researchers can employ pH-responsive indicators like bromothymol blue to visually track changes in real time. Additionally, storing cultures at 4°C can slow metabolic activity, delaying pH shifts. When staining aged cultures, extending the staining time by 10–15 minutes can compensate for reduced spore permeability caused by pH changes. For precise control, using pH-stabilized staining solutions, such as those containing 0.05% Tween 80, can enhance spore coat penetration even in suboptimal pH conditions.

In conclusion, pH changes during culture aging pose a tangible threat to spore stain viability, necessitating proactive management. By combining regular pH monitoring, buffer systems, and age-specific staining adjustments, researchers can ensure accurate and reproducible results. Ignoring these factors risks compromising data integrity, particularly in studies reliant on spore detection for diagnostic or research purposes.

Understanding Anthrax Spores: Formation, Survival, and Deadly Resilience Explained

You may want to see also

Effect of nutrient depletion on spore stain morphology over time

Nutrient depletion in microbial cultures significantly alters spore stain morphology over time, a phenomenon critical for microbiologists to understand. As nutrients become scarce, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* shift from vegetative growth to sporulation, a survival mechanism. Initially, young cultures (24–48 hours) exhibit few spores, as energy is directed toward cell division. However, as nutrients deplete (typically after 72 hours), sporulation increases, leading to a higher density of spores in older cultures. This shift is evident in spore stains, where older cultures show more distinct, refractile spores under microscopy compared to younger, nutrient-rich cultures.

To observe this effect, prepare a nutrient agar plate inoculated with *Bacillus subtilis* and incubate at 37°C. After 24 hours, perform a spore stain using the Schaeffer-Fulton method: heat-fix a smear, apply malachite green for 5 minutes, and counterstain with safranin. Examine under 1000x magnification. Repeat the staining process at 48, 72, and 96 hours. Note the increasing spore-to-vegetative cell ratio, with older cultures displaying more mature, phase-bright spores. This progression underscores the direct correlation between nutrient depletion and sporulation efficiency.

From a practical standpoint, nutrient depletion not only increases spore count but also affects spore morphology. In nutrient-rich conditions, spores may appear smaller and less defined due to incomplete maturation. Conversely, prolonged nutrient depletion (beyond 96 hours) can lead to spore degradation or germination, as the culture enters a decline phase. For optimal spore staining, harvest cultures at 72–96 hours, when sporulation peaks. Avoid over-incubation, as it may result in false negatives or ambiguous results due to spore lysis or germination.

Comparatively, nutrient-rich cultures prioritize vegetative growth, yielding fewer spores with less distinct morphology. This difference is crucial in clinical and industrial settings, where accurate spore identification is essential. For instance, in food safety testing, older cultures from spoiled samples may show abundant spores, indicating bacterial stress and potential contamination. Conversely, young cultures from fresh samples may lack spores, suggesting active growth rather than survival mode. Understanding this dynamic ensures precise interpretation of spore stains in diagnostic and quality control applications.

In conclusion, nutrient depletion drives a predictable shift in spore stain morphology, from sparse, immature spores in young cultures to abundant, mature spores in older ones. By monitoring culture age and nutrient availability, microbiologists can optimize staining protocols and interpret results with greater accuracy. Practical tips include harvesting cultures at 72–96 hours, avoiding over-incubation, and correlating spore morphology with nutrient conditions. This knowledge not only enhances laboratory techniques but also deepens insights into bacterial survival strategies under stress.

Can Black Mold Spores Spread Through Furnace Pipes? Find Out

You may want to see also

Role of temperature fluctuations in altering spore stain characteristics

Temperature fluctuations during spore staining can significantly alter the final characteristics of the stain, impacting both its clarity and diagnostic value. Spores, being resilient structures, are generally resistant to environmental changes, but their staining properties are not immune to temperature variations. For instance, the commonly used Schaeffer-Fulton method relies on precise heating steps to decolorize and counterstain the sample. Deviations from the optimal temperature range (typically 80-100°C for heat fixation) can lead to incomplete spore staining or background contamination. A temperature that is too low may fail to adequately heat-fix the spores, resulting in a washed-out appearance, while excessive heat can cause non-specific staining of debris or cellular material, obscuring the spores.

Consider the following scenario: a laboratory technician stains *Bacillus subtilis* spores using the Dorner method, which involves heating the primary stain (malachite green) to steam for 5-10 minutes. If the temperature is inconsistently applied—say, fluctuating between 90°C and 110°C—some spores may retain excessive stain, appearing overly dark, while others may lose the stain prematurely, leading to false negatives. This variability undermines the reliability of the stain, particularly in clinical or industrial settings where accurate spore identification is critical.

To mitigate these issues, laboratories should adhere to strict temperature control protocols. Digital hotplates or water baths with thermostatic regulation are recommended over open flames, which are prone to temperature spikes. For example, maintaining a consistent 95°C during the steaming step ensures uniform penetration of the malachite green stain without causing thermal degradation of the spore coat. Additionally, pre-testing temperature equipment and calibrating it regularly can prevent inadvertent fluctuations.

A comparative analysis of temperature-controlled versus uncontrolled staining reveals stark differences. In a study where *Clostridium* spores were stained at 85°C, 95°C, and 105°C, the 95°C samples exhibited the sharpest contrast between spores and vegetative cells, while the 85°C samples showed faint staining and the 105°C samples displayed background discoloration. This highlights the critical role of temperature precision in achieving optimal staining outcomes.

In conclusion, temperature fluctuations are not merely minor inconveniences but potential sources of error in spore staining. By understanding their impact and implementing rigorous temperature control measures, laboratories can enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of their results. Practical tips include using calibrated equipment, monitoring temperature in real-time, and standardizing heating durations to account for specific spore species and staining methods. Such attention to detail ensures that temperature remains an ally, not an adversary, in the spore staining process.

Can Apple TV Spread Spores? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.99

Influence of osmotic stress on spore stain integrity during aging

Osmotic stress, induced by variations in solute concentration, can significantly alter the integrity of spore stains during the aging process. When spores are exposed to hypertonic conditions, water efflux occurs, leading to cellular dehydration. This dehydration can cause shrinkage of the spore’s outer layers, potentially disrupting the binding sites for stains like malachite green or safranin. Conversely, hypotonic environments may cause spore swelling, which can dilute intracellular components and reduce the stain’s ability to penetrate effectively. Understanding these osmotic effects is crucial for maintaining consistent staining results in aging cultures.

To mitigate osmotic stress during spore staining, researchers should carefully control the solute concentration of the culture medium. For example, maintaining a balanced osmolarity of 0.85–0.9% NaCl in the medium can mimic physiological conditions and minimize stress. If osmotic shock is unavoidable, pre-treating spores with gradual osmotic adjustments (e.g., stepwise increases or decreases in salt concentration) can help acclimate them to the stress. Additionally, using protective agents like trehalose or glycerol in the staining solution can stabilize spore membranes and preserve stain integrity.

A comparative analysis of spore stains from young (24–48 hours) and aged cultures (7–14 days) under varying osmotic conditions reveals striking differences. Aged spores exposed to hypertonic stress often exhibit patchy or incomplete staining, indicating compromised cell wall integrity. In contrast, young spores under similar conditions retain uniform staining due to their robust cellular structure. This highlights the importance of monitoring culture age and osmotic environment when interpreting staining results. For optimal outcomes, stain aged cultures within 24 hours of osmotic exposure to minimize artifactual changes.

Practical tips for preserving spore stain integrity include avoiding abrupt changes in osmotic pressure during culture maintenance. For instance, when transferring spores to staining solutions, use buffers with matched osmolarity to prevent shock. If working with aged cultures, consider rehydrating spores in isotonic solutions before staining to restore their structural integrity. Finally, document the osmotic history of the culture, as this can provide valuable context for interpreting staining outcomes. By addressing osmotic stress proactively, researchers can ensure reliable and reproducible spore staining across all culture ages.

Exploring the Potential for Spore Mines to Advance in Modern Warfare

You may want to see also

Changes in spore coat composition due to prolonged culture aging

Prolonged culture aging can significantly alter the composition of spore coats, impacting their staining properties and overall viability. As cultures age, metabolic shifts occur, leading to changes in the synthesis and deposition of spore coat components such as proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides. For instance, older cultures of *Bacillus subtilis* have been observed to produce spores with thicker coats, which can hinder the penetration of common stains like malachite green or safranin. This phenomenon is not merely a cosmetic issue; it directly affects the accuracy of spore enumeration and viability assessments in laboratory settings.

To mitigate these effects, researchers must adopt specific strategies. One practical approach is to standardize culture age during spore production, ideally harvesting spores from cultures in the mid-exponential to early stationary phase. For example, spores harvested after 24–48 hours of *B. subtilis* culture growth typically exhibit optimal staining characteristics. Beyond this window, the spore coat may become more resistant to staining agents, necessitating longer incubation times or higher concentrations of dyes. However, increasing dye concentration can lead to nonspecific background staining, complicating interpretation.

A comparative analysis of young versus aged cultures reveals distinct trends. Spores from younger cultures often stain uniformly and brightly, indicating a more accessible and less complex coat structure. In contrast, aged spores may show patchy or incomplete staining, suggesting altered coat permeability or increased cross-linking of coat proteins. For instance, prolonged aging in *Clostridium botulinum* cultures has been linked to elevated levels of sporulation-specific proteins, which can form denser coat layers. This underscores the need for species-specific protocols when working with aged cultures.

From a practical standpoint, laboratories should implement rigorous documentation of culture age and staining outcomes. Maintaining detailed records allows for the identification of age-related trends and the establishment of optimal harvesting times. Additionally, alternative staining techniques, such as heat or chemical pretreatments, can be employed to enhance dye penetration in aged spores. For example, a 10-minute incubation at 80°C prior to staining has been shown to improve malachite green uptake in aged *Bacillus cereus* spores. Such adaptations ensure that aging-induced changes in spore coat composition do not compromise experimental accuracy.

In conclusion, understanding the dynamic relationship between culture age and spore coat composition is essential for reliable spore staining. By recognizing the metabolic and structural changes that occur during prolonged aging, researchers can implement targeted strategies to maintain staining efficacy. Whether through standardized harvesting protocols, pretreatment methods, or species-specific adjustments, proactive measures ensure that age-related alterations in spore coats do not impede scientific inquiry. This knowledge not only enhances laboratory practices but also contributes to the broader understanding of spore biology and its applications.

Milorganite and Milky Spores: Can You Apply Them Together?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Culture age significantly affects spore stain results because older cultures tend to produce more spores, leading to a higher density of spores in the stain. Younger cultures may show fewer or no spores, making them harder to visualize.

Yes, if the culture is too young, it may not have produced enough spores to be detected, resulting in a false negative. Proper incubation time is crucial for accurate spore staining.

Culture age can affect staining intensity. Older cultures with mature spores may stain more intensely due to thicker spore walls, while younger spores may appear lighter or less defined under the microscope.