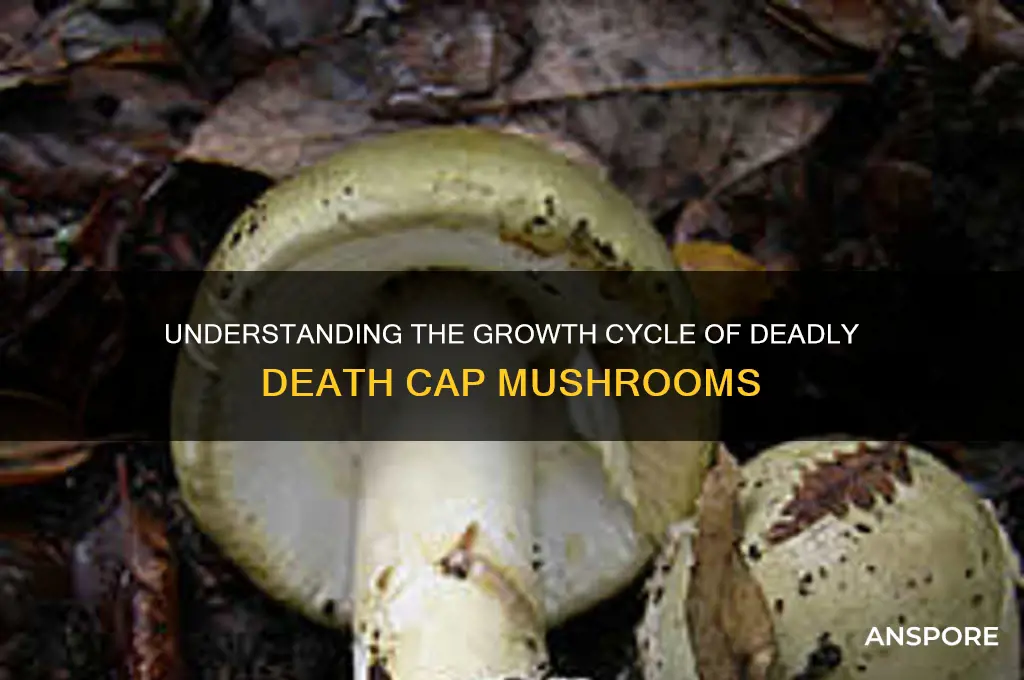

The death cap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is a highly toxic fungus notorious for its deadly potential, yet its growth and ecology are fascinating subjects of study. This mushroom thrives in symbiotic relationships with various tree species, particularly oaks, birches, and pines, forming mycorrhizal associations where the fungus exchanges nutrients with the tree roots. It prefers temperate climates and is commonly found in Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, often appearing in woodland areas with rich, well-drained soil. The death cap typically grows in the summer and autumn months, emerging from the ground as a distinctive greenish-yellow cap with white gills and a bulbous base. Its growth is influenced by factors such as soil pH, moisture levels, and the presence of compatible tree hosts, making it a specialized yet widespread species in its favored habitats. Understanding its growth patterns is crucial not only for ecological research but also for public safety, as accidental ingestion can be fatal.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Amanita phalloides |

| Common Name | Death Cap |

| Growth Habitat | Mycorrhizal association with trees, particularly oak, beech, and pine. |

| Soil Preference | Prefers calcareous (chalky or lime-rich) soils. |

| Climate | Thrives in temperate climates with mild, moist conditions. |

| Season | Typically grows in late summer to autumn (August to November). |

| Fruiting Body | Distinctive greenish-yellow cap, 5–15 cm in diameter, with white gills. |

| Stem | Slender, 8–15 cm tall, with a bulbous base and a skirt-like ring. |

| Spores | White, smooth, and elliptical, released from gills under the cap. |

| Toxicity | Contains amatoxins (e.g., alpha-amanitin), which cause severe liver damage. |

| Growth Rate | Slow to moderate, taking several weeks to fully mature. |

| Reproduction | Sexually via spores and vegetatively through mycelial networks. |

| Ecosystem Role | Symbiotic with trees, aiding nutrient uptake in exchange for carbohydrates. |

| Geographic Distribution | Native to Europe, but introduced to North America, Australia, and Asia. |

| Distinctive Features | Volva (cup-like structure at the base) and persistent ring on the stem. |

| Edibility | Extremely poisonous, often fatal if ingested. |

| Conservation Status | Not endangered, but spread is monitored due to toxicity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores and Dispersal: Death cap mushrooms spread via wind-borne spores, landing in soil to germinate

- Mycorrhizal Relationship: They form symbiotic bonds with tree roots, aiding nutrient exchange for growth

- Optimal Conditions: Thrive in moist, shady environments with rich, alkaline soil and deciduous trees

- Life Cycle Stages: Begins as spores, develops mycelium, then fruiting bodies (mushrooms) appear seasonally

- Geographic Distribution: Commonly found in Europe, North America, and Australia near oak, beech, and pine trees

Spores and Dispersal: Death cap mushrooms spread via wind-borne spores, landing in soil to germinate

The death cap mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, relies heavily on its spores for propagation. These spores are microscopic, single-celled structures produced in vast quantities beneath the mushroom's cap. When the mushroom reaches maturity, the gills release the spores into the surrounding environment. This process is crucial for the fungus's life cycle, as it ensures the dispersal of genetic material over a wide area. The spores are incredibly lightweight, allowing them to be carried by even the gentlest breeze, which is essential for their dispersal mechanism.

Wind plays a pivotal role in the dispersal of death cap mushroom spores. Once released, the spores can travel significant distances, often far beyond the immediate vicinity of the parent mushroom. This wind-borne dispersal is highly efficient, enabling the species to colonize new habitats and expand its range. The spores' ability to remain airborne for extended periods increases the likelihood of them encountering suitable environments for germination. This natural process is a key factor in the mushroom's success as an invasive species in many regions.

Upon landing in the soil, a death cap mushroom spore requires specific conditions to germinate. The soil must be rich in organic matter and have a slightly acidic pH, typically found in deciduous and coniferous forests. Moisture is also critical, as it activates the spore and initiates the germination process. Once germinated, the spore develops into a hypha, a thread-like structure that grows and branches out, forming a network called the mycelium. This mycelium is the vegetative part of the fungus and is responsible for nutrient absorption.

The mycelium grows underground, often forming symbiotic relationships with tree roots, particularly those of oaks, beeches, and pines. This mutualistic association, known as mycorrhiza, benefits both the fungus and the tree. The tree provides carbohydrates to the fungus, while the fungus enhances the tree's ability to absorb water and nutrients from the soil. Over time, under the right conditions of temperature and moisture, the mycelium develops fruiting bodies—the mushrooms we see above ground. These mushrooms then produce and release spores, completing the life cycle.

Understanding the spore dispersal and germination process of the death cap mushroom is crucial for both ecological and safety reasons. The mushroom's ability to spread via wind-borne spores makes it a persistent and widespread species, often appearing in new areas where it can pose a significant risk to humans and animals due to its toxicity. By studying these mechanisms, researchers can develop strategies to manage and control its spread, while also gaining insights into the broader dynamics of fungal ecosystems. This knowledge is invaluable for both conservation efforts and public health initiatives.

Mushrooms in Your Indoor Plant? Causes and Solutions Explained

You may want to see also

Mycorrhizal Relationship: They form symbiotic bonds with tree roots, aiding nutrient exchange for growth

The death cap mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, thrives through a complex and mutually beneficial relationship with tree roots called a mycorrhizal association. This symbiotic bond is fundamental to its growth and survival. In this relationship, the fungus forms a network of thread-like structures called hyphae around and within the roots of trees, primarily oaks, beeches, and pines. This intimate connection allows the death cap mushroom to access nutrients that are otherwise difficult to obtain, while the tree benefits from enhanced water and nutrient uptake. The mycorrhizal relationship is not just a passive interaction but a dynamic partnership that drives the growth of both the fungus and its host tree.

The nutrient exchange in this mycorrhizal relationship is a key factor in the death cap mushroom's ability to grow and spread. Trees absorb essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and minerals from the soil, but these elements are often locked in forms that are inaccessible to the fungus alone. Through the mycorrhizal bond, the fungus extends its hyphal network far beyond the tree's root system, increasing the surface area for nutrient absorption. The hyphae secrete enzymes that break down complex organic matter, releasing nutrients that are then shared with the tree. In return, the tree provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis, which are vital for fungal growth and reproduction.

This symbiotic relationship also enhances the death cap mushroom's resilience in various environmental conditions. The hyphal network improves soil structure, increasing water retention and aeration, which benefits both the fungus and the tree. Additionally, the mycorrhizal association can protect the tree from pathogens and toxins in the soil, indirectly supporting the mushroom's growth by ensuring the health of its host. This mutual protection and resource sharing create a stable environment for the death cap mushroom to develop its fruiting bodies, the visible mushrooms we see above ground.

The growth of death cap mushrooms is deeply intertwined with the health and vitality of their host trees. Young trees often form mycorrhizal relationships with *Amanita phalloides* early in their development, and this partnership continues throughout their lifespan. The fungus relies on the tree for carbohydrates and a stable habitat, while the tree gains improved nutrient and water uptake. This interdependence highlights the importance of preserving healthy forest ecosystems, as disruptions to tree health can directly impact the growth and prevalence of death cap mushrooms.

Understanding the mycorrhizal relationship of the death cap mushroom provides valuable insights into its ecology and growth patterns. By forming symbiotic bonds with tree roots, the fungus gains access to essential nutrients and creates a supportive environment for both itself and its host. This relationship is not only crucial for the mushroom's survival but also plays a significant role in forest ecosystems, influencing nutrient cycling and plant health. Studying these interactions can help researchers better understand the conditions under which death cap mushrooms thrive and develop strategies to manage their presence in affected areas.

Mushroom Growth on ACNL Island: Facts and Tips for Players

You may want to see also

Optimal Conditions: Thrive in moist, shady environments with rich, alkaline soil and deciduous trees

The death cap mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, thrives under specific environmental conditions that mimic its native habitats in Europe. One of the most critical factors for its growth is moisture. These mushrooms prefer consistently damp environments, often found in areas with high humidity or regular rainfall. The soil must retain moisture without becoming waterlogged, as excessive water can hinder mycelial growth. Mulch or leaf litter on the forest floor helps maintain this balance by slowly releasing moisture, creating an ideal substrate for the death cap to flourish.

Shade is another essential element in the death cap's optimal growth conditions. These mushrooms are typically found in shaded areas, such as beneath the canopy of deciduous trees, where direct sunlight is minimal. The shade not only helps retain soil moisture but also prevents rapid evaporation, ensuring the mycelium remains hydrated. This preference for low-light environments is why death caps are rarely found in open fields or sun-exposed areas, instead favoring the understory of dense forests.

The soil composition plays a pivotal role in the death cap's lifecycle. These mushrooms prefer rich, alkaline soil with a pH level slightly above neutral, typically between 7.0 and 8.0. The soil should be nutrient-dense, often enriched by decaying organic matter from fallen leaves, wood, and other forest debris. This alkaline environment supports the symbiotic relationship between the death cap and the roots of deciduous trees, particularly oak, beech, and chestnut, which are commonly found in its natural habitats.

Deciduous trees are integral to the death cap's ecosystem. These mushrooms form mycorrhizal associations with the roots of such trees, exchanging nutrients for carbohydrates. The presence of deciduous trees not only provides the necessary shade and organic matter but also ensures the soil remains alkaline due to the type of leaf litter they produce. This symbiotic relationship is so specific that death caps are rarely found outside of forests dominated by these tree species.

To cultivate death caps or understand their growth in the wild, replicating these optimal conditions is key. Creating a moist, shady environment with rich, alkaline soil and incorporating deciduous trees or their leaf litter will mimic their natural habitat. However, it is crucial to note that while these conditions support their growth, the death cap remains one of the most poisonous mushrooms in the world, and its cultivation should be approached with extreme caution or avoided altogether.

Unseen Fungi Within: Exploring Mushrooms' Hidden Presence in the Human Body

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Stages: Begins as spores, develops mycelium, then fruiting bodies (mushrooms) appear seasonally

The life cycle of the infamous Death Cap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is a fascinating yet deadly process, beginning with the dispersal of spores. These spores are microscopic, single-celled structures produced in vast quantities within the gills of the mature mushroom. When released, they are carried by wind, water, or animals to new locations, marking the first stage of the fungus's life cycle. Each spore has the potential to develop into a new organism under suitable conditions, typically requiring a moist and nutrient-rich environment. This initial phase is crucial for the mushroom's survival and propagation, as it allows the species to colonize new areas and ensure its continuity.

Upon landing in a favorable habitat, often among the roots of broadleaf trees, the spore germinates and grows into a network of thread-like filaments called mycelium. This stage is the vegetative part of the fungus's life cycle and can remain hidden beneath the soil or within decaying wood for extended periods. The mycelium plays a vital role in nutrient absorption, breaking down organic matter and extracting essential elements for growth. As it expands, it forms a symbiotic relationship with tree roots, known as mycorrhiza, which benefits both the fungus and the host plant. This mutualistic association is key to the Death Cap's success, providing it with a steady supply of nutrients and a stable environment for growth.

Under the right conditions, typically in late summer to autumn when temperatures are cooler and moisture is abundant, the mycelium initiates the formation of fruiting bodies—the mushrooms we commonly recognize. This transition is triggered by various environmental cues, including changes in temperature, humidity, and daylight duration. The fruiting bodies emerge from the soil, rapidly developing into the distinctive Death Cap mushrooms with their olive-green caps and white gills. This seasonal appearance is a strategy to maximize spore dispersal, as the mushrooms release their spores into the environment, starting the life cycle anew.

The growth of the fruiting bodies is a rapid process, often taking just a few days from initial emergence to full maturity. During this time, the mushrooms undergo significant changes, with the cap expanding and the gills maturing to produce and release spores. The seasonal nature of this growth ensures that the mushrooms appear when conditions are optimal for spore dispersal and mycelium development. After releasing their spores, the mushrooms begin to degrade, returning nutrients to the soil and completing the life cycle. This cyclical process highlights the resilience and adaptability of the Death Cap mushroom, contributing to its widespread presence in various ecosystems.

Understanding the life cycle stages of the Death Cap mushroom is essential for both mycological study and public safety. Its ability to form mycorrhizal associations and produce abundant spores contributes to its success as a species, but also poses a significant risk to humans due to its extreme toxicity. By recognizing the stages of spore dispersal, mycelium growth, and seasonal fruiting, one can better appreciate the complexity of this organism's life cycle and the importance of accurate identification to prevent accidental poisoning.

Discovering the Best Trees for Oyster Mushrooms to Thrive On

You may want to see also

Geographic Distribution: Commonly found in Europe, North America, and Australia near oak, beech, and pine trees

The death cap mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, has a geographic distribution that spans several continents, with a particular affinity for specific environments. Commonly found in Europe, this deadly fungus thrives in the temperate climates of countries such as France, Italy, and Germany. It often grows in symbiotic relationships with deciduous trees, especially oak and beech, in both natural forests and urban parks. The mushroom’s presence in Europe is well-documented, and its association with these tree species makes it a frequent, yet dangerous, sight in wooded areas.

In North America, the death cap mushroom has established itself as an invasive species, particularly in the western regions of the United States, such as California and the Pacific Northwest. Here, it is often found near oak and pine trees, mirroring its European habitat preferences. Its spread in North America is attributed to the accidental introduction of its spores through imported trees or soil. Despite being non-native, it has adapted remarkably well to the local ecosystems, posing a significant risk to foragers and wildlife alike.

Australia is another continent where the death cap mushroom has gained a foothold, primarily in urban areas with introduced European tree species. It is commonly found near oak and pine trees in cities like Canberra and Melbourne. The mushroom’s presence in Australia is relatively recent, likely introduced through landscaping practices involving European trees. Its ability to form mycorrhizal associations with these trees has allowed it to thrive in non-native environments, making it a growing concern for local authorities and mushroom enthusiasts.

The consistent presence of the death cap mushroom near oak, beech, and pine trees across its range highlights its ecological niche. These trees provide the necessary conditions for its growth, including suitable soil pH and nutrient availability. The mushroom’s mycelium forms a mutualistic relationship with the tree roots, aiding in nutrient uptake while receiving carbohydrates in return. This dependency on specific tree species explains its localized distribution within broader geographic areas.

Understanding the geographic distribution of the death cap mushroom is crucial for public safety and ecological management. Its preference for oak, beech, and pine trees serves as a key identifier for potential habitats. In Europe, North America, and Australia, awareness campaigns often focus on these tree species to educate the public about the risks of misidentifying this deadly fungus. By recognizing its habitat associations, individuals can better avoid accidental poisoning and contribute to the monitoring of its spread in new areas.

Can Lions Mane Mushrooms Thrive in Minnesota's Climate and Forests?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Death Cap mushrooms (Amanita phalloides) thrive in temperate climates with mild, moist conditions. They prefer symbiotic relationships with trees, often growing near oak, beech, and pine trees in well-drained, acidic soil.

From spore germination to mature fruiting body, Death Cap mushrooms typically take 10–14 days to fully develop, depending on environmental conditions like temperature and humidity.

Death Cap mushrooms can grow in both forested areas and urban environments, especially in parks, gardens, or yards with suitable tree hosts and soil conditions.

Death Cap mushrooms often grow in clusters or groups near their host trees, though individual specimens can also appear. Their mycelium network spreads underground, supporting multiple fruiting bodies.