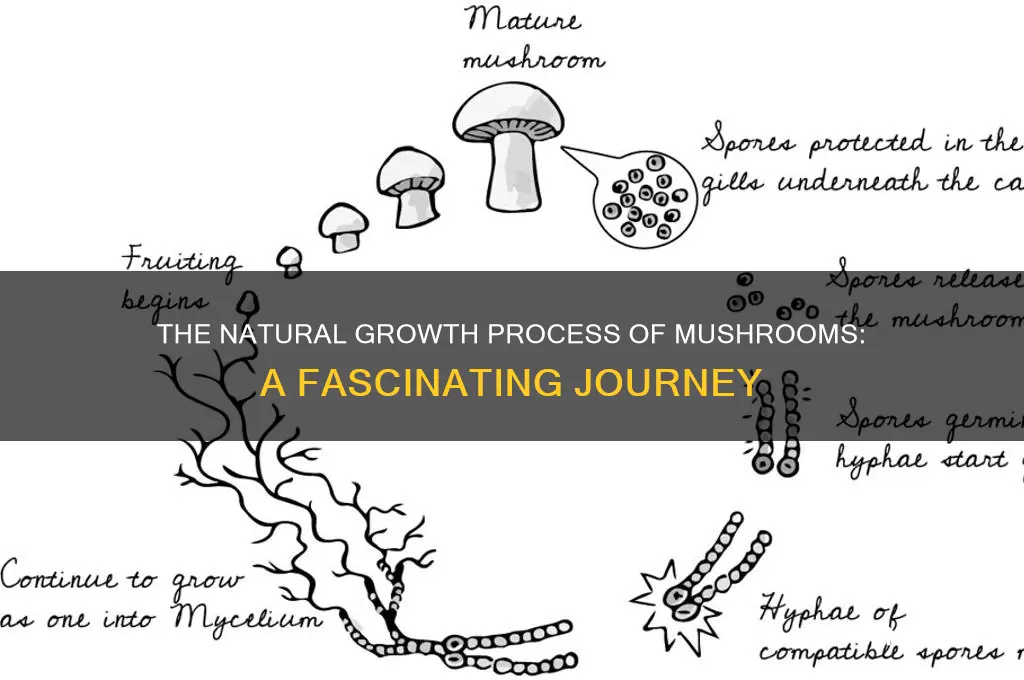

Mushrooms grow naturally through a fascinating process that begins with spores, which are akin to the seeds of plants. These microscopic spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals and land on suitable substrates like decaying wood, soil, or leaf litter. When conditions are right—typically involving moisture, warmth, and organic matter—the spores germinate and develop into thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae intertwine to form a network known as mycelium, which acts as the mushroom's root system, absorbing nutrients from its environment. Over time, under optimal conditions of humidity and temperature, the mycelium produces fruiting bodies—the visible mushrooms—which emerge to release new spores, completing the life cycle. This natural growth process highlights the mushroom's role as a decomposer and its importance in nutrient cycling within ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Substrate | Mushrooms grow naturally on organic matter such as decaying wood, leaves, soil, or animal dung. Common substrates include hardwood logs, straw, compost, and manure. |

| Mycelium | The vegetative part of the fungus, mycelium, colonizes the substrate first, breaking down organic material to extract nutrients. It is a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. |

| Spores | Mushrooms reproduce via spores, which are dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Spores germinate under suitable conditions to form new mycelium. |

| Environmental Conditions | Requires specific conditions: temperature (typically 55–75°F or 13–24°C), humidity (above 85%), and indirect light. Darkness is often needed for initial mycelium growth. |

| Moisture | Adequate moisture is essential for mushroom growth, as they absorb water through their mycelium and fruiting bodies. |

| pH Level | Most mushrooms prefer a slightly acidic to neutral pH range (5.0–7.0) in the substrate. |

| Fruiting Bodies | The visible part of the mushroom (e.g., cap and stem) emerges when the mycelium is mature and conditions are optimal. This stage is called fruiting. |

| Growth Time | Varies by species; some mushrooms fruit within weeks, while others take months or years to develop. |

| Ecosystem Role | Mushrooms play a key role in ecosystems as decomposers, breaking down complex organic materials and recycling nutrients. |

| Seasonality | Many mushrooms grow seasonally, often in spring, fall, or after rainfall, depending on the species and climate. |

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

- Spore Dispersal: Spores released into air, carried by wind, water, or animals to new habitats

- Substrate Colonization: Mycelium grows, breaks down organic matter like wood or soil for nutrients

- Fruiting Conditions: Triggered by humidity, temperature, and light changes, mushrooms emerge from mycelium

- Pinhead Formation: Tiny mushroom primordia develop from mycelium, growing into mature fruiting bodies

- Sporocarp Maturation: Caps expand, gills release spores, completing the natural growth and reproduction cycle

Spore Dispersal: Spores released into air, carried by wind, water, or animals to new habitats

Mushrooms, like other fungi, reproduce through the dispersal of spores, which are microscopic, single-celled structures analogous to plant seeds. Spore dispersal is a critical step in the natural growth cycle of mushrooms, ensuring their propagation to new habitats. When a mushroom reaches maturity, its gills or pores, located on the underside of the cap, produce and release vast quantities of spores into the surrounding environment. This release is often facilitated by environmental factors such as air currents, moisture, or even the movement of nearby organisms. Once liberated, spores are remarkably lightweight and can remain suspended in the air for extended periods, allowing them to travel significant distances.

Wind plays a primary role in spore dispersal, acting as a natural carrier that transports spores across vast areas. As spores are released, they are easily picked up by air currents, which can carry them from their origin to distant locations. This method of dispersal is particularly effective for mushrooms growing in open environments, such as meadows or forests, where air movement is unimpeded. The efficiency of wind dispersal is enhanced by the sheer number of spores produced by a single mushroom, often numbering in the millions, ensuring that at least some spores will land in suitable environments for growth.

Water also serves as a medium for spore dispersal, especially in humid or aquatic environments. Spores released near water bodies, such as streams, ponds, or damp soil, can be carried away by flowing water or splashes caused by rain. This method is particularly important for mushrooms that thrive in moist habitats, as water not only transports spores but also provides the necessary moisture for their germination. Additionally, water can carry spores into crevices or soil layers that might be inaccessible by wind, increasing the chances of successful colonization.

Animals and insects contribute significantly to spore dispersal, often inadvertently aiding mushrooms in reaching new habitats. As animals move through mushroom-rich areas, spores can adhere to their fur, feathers, or exoskeletons. When these animals travel to different locations, they carry the spores with them, depositing them in new environments through grooming, defecation, or simply brushing against surfaces. Insects, particularly flies and beetles, are also effective spore carriers, as they are attracted to mushrooms for feeding or breeding purposes. This animal-mediated dispersal is especially beneficial for mushrooms growing in dense forests or understory environments where wind and water dispersal might be limited.

The success of spore dispersal ultimately depends on the spores landing in environments conducive to growth, such as nutrient-rich soil, decaying wood, or other organic matter. Once a spore settles in a suitable location, it germinates under the right conditions of moisture, temperature, and nutrients, developing into a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae grow and spread, eventually forming the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. Over time, if conditions are favorable, the mycelium will produce a fruiting body—the mushroom—completing the life cycle and preparing for the next round of spore dispersal. This natural process ensures the survival and proliferation of mushroom species across diverse ecosystems.

Do Morel Mushrooms Return Annually to Their Favorite Foraging Spots?

You may want to see also

Substrate Colonization: Mycelium grows, breaks down organic matter like wood or soil for nutrients

Mushroom growth begins with the colonization of a substrate by mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus. Mycelium is a network of thread-like structures called hyphae that act as the fungus’s primary means of nutrient absorption and growth. In nature, mycelium seeks out organic matter such as wood, leaves, soil, or compost, which serves as the substrate—the material it colonizes and breaks down. This process is essential for the fungus to obtain the nutrients necessary for growth and eventual mushroom formation. The mycelium secretes enzymes that decompose complex organic materials like cellulose and lignin in wood, or chitin in decaying plant matter, converting them into simpler compounds it can absorb.

Substrate colonization is a highly efficient and targeted process. Once the mycelium comes into contact with a suitable substrate, it begins to grow and spread rapidly, penetrating the material with its hyphae. This penetration allows the mycelium to access the nutrients locked within the substrate. As the hyphae grow, they form a dense network that strengthens the colonization process, ensuring maximum nutrient extraction. The mycelium’s ability to break down tough organic matter, such as wood, is particularly remarkable, as it plays a crucial role in nutrient cycling in ecosystems by decomposing materials that other organisms cannot easily process.

The breakdown of organic matter by mycelium is a biochemical process driven by enzymes. These enzymes are released into the substrate, where they catalyze the breakdown of complex molecules into simpler forms like sugars, amino acids, and minerals. The mycelium then absorbs these nutrients directly through its cell walls, fueling its growth and expansion. This process not only sustains the fungus but also enriches the surrounding environment by recycling organic materials into forms that other organisms can use. In this way, mycelium acts as a primary decomposer in many ecosystems, contributing to soil health and fertility.

As the mycelium colonizes the substrate, it creates a symbiotic relationship with its environment. In some cases, this relationship extends to plants through mycorrhizal associations, where the mycelium helps plants absorb water and nutrients in exchange for carbohydrates produced by photosynthesis. However, in the context of mushroom growth, the focus remains on the mycelium’s ability to break down and utilize the substrate for its own development. Once the substrate is fully colonized and the mycelium has accumulated sufficient nutrients, it can redirect its energy toward fruiting body formation—the mushrooms we see above ground.

The success of substrate colonization depends on several factors, including the type of substrate, environmental conditions like temperature and humidity, and the specific fungal species involved. Different fungi have adapted to colonize various substrates, from the hardwood-loving shiitake mushroom to the straw-decomposing oyster mushroom. Understanding these preferences is crucial for both natural mushroom growth and cultivation practices. By mimicking the conditions that favor substrate colonization, growers can encourage healthy mycelium development and, ultimately, abundant mushroom yields. This natural process highlights the mycelium’s role as a master decomposer and nutrient recycler in the fungal life cycle.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Edible Fungi at Home

You may want to see also

Fruiting Conditions: Triggered by humidity, temperature, and light changes, mushrooms emerge from mycelium

Mushrooms, the visible fruiting bodies of fungi, emerge from a network of thread-like structures called mycelium, which grows underground or within organic matter. The transition from mycelium to mushroom is a critical phase known as fruiting, which is triggered by specific environmental conditions. Humidity plays a pivotal role in this process, as mycelium requires high moisture levels to initiate fruiting. In nature, this often occurs after rainfall or in damp environments, where water availability signals to the mycelium that conditions are favorable for spore production. Without sufficient humidity, the mycelium remains dormant, conserving energy and resources.

Temperature is another crucial factor in triggering fruiting. Different mushroom species have specific temperature ranges within which they thrive. For example, some mushrooms prefer cooler temperatures, while others require warmth to initiate fruiting. In natural settings, seasonal temperature changes often act as a cue for mycelium to begin forming mushrooms. A sudden drop in temperature, such as the onset of autumn, can stimulate fruiting in many species. This temperature shift, combined with adequate humidity, creates an ideal environment for mushrooms to emerge.

Light changes also play a significant role in fruiting, though their influence is less direct compared to humidity and temperature. Many mushroom species are sensitive to light, particularly changes in light duration or intensity. For instance, some fungi require near-darkness to fruit, while others may respond to increased light exposure. In nature, light changes often coincide with seasonal shifts, such as shorter days in autumn, which can trigger fruiting. Light acts as a secondary signal, fine-tuning the mycelium's response to humidity and temperature cues.

The interplay of these factors—humidity, temperature, and light—creates a precise set of conditions that prompt mycelium to allocate energy toward mushroom formation. Once these conditions are met, the mycelium redirects its resources into developing fruiting bodies, which will eventually release spores to propagate the species. This process is highly efficient, ensuring that mushrooms appear when environmental conditions maximize their chances of spore dispersal. Understanding these fruiting conditions is essential for both naturalists and cultivators, as it highlights the delicate balance required for mushrooms to grow naturally.

In summary, the emergence of mushrooms from mycelium is a response to specific environmental triggers: high humidity, optimal temperature, and appropriate light changes. These conditions signal to the mycelium that it is time to produce fruiting bodies, ensuring the continuation of the fungal life cycle. By observing these natural processes, we gain insight into the intricate relationship between fungi and their environment, as well as practical knowledge for cultivating mushrooms successfully.

Master Outdoor Mushroom Cultivation: Simple Steps for Bountiful Harvests

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pinhead Formation: Tiny mushroom primordia develop from mycelium, growing into mature fruiting bodies

Mushroom growth begins with the mycelium, a network of thread-like structures called hyphae that spread through the substrate, such as soil or decaying wood. The mycelium is the vegetative part of the fungus and is responsible for nutrient absorption. Under favorable conditions—adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrients—the mycelium initiates the development of mushroom primordia, the earliest stage of fruiting body formation. These primordia are microscopic at first, forming as tiny knots or aggregations of cells within the mycelial network. This stage marks the transition from the mycelium's focus on nutrient acquisition to the reproductive phase, where energy is directed toward producing spores.

Pinhead formation is the next visible stage in mushroom development, where the primordia grow into small, pin-like structures. These pinheads are the first recognizable signs of mushroom formation and typically appear as tiny bumps on the substrate or within the mycelium. The process is driven by cellular differentiation, where hyphae reorganize to form the specialized tissues of the fruiting body. At this stage, the pinheads are highly sensitive to environmental conditions; consistent humidity, proper ventilation, and stable temperatures are crucial for their continued growth. Any stress, such as drought or extreme temperatures, can halt development or cause the pinheads to abort.

As the pinheads mature, they elongate and expand into the familiar mushroom shape, consisting of a stem and a cap. The cap houses the gills, pores, or spines, depending on the mushroom species, which are essential for spore production. During this growth phase, the mushroom primordia rely on the mycelium for water and nutrients, which are transported through the hyphal network. The rapid growth of the fruiting body is fueled by stored carbohydrates and other resources accumulated by the mycelium. This stage is characterized by visible and rapid changes, often occurring within days under optimal conditions.

The transition from pinhead to mature fruiting body is a complex process involving coordinated cell division, expansion, and differentiation. The cap and stem develop distinct structures, such as the veil (in some species) and the spore-bearing surface. Once the mushroom reaches maturity, it releases spores into the environment, ensuring the dispersal and continuation of the fungal species. After spore release, the fruiting body begins to degrade, returning nutrients to the mycelium and completing the life cycle. Pinhead formation, therefore, is a critical step in this natural process, bridging the gap between the hidden mycelium and the visible mushroom.

Understanding pinhead formation is essential for both natural mushroom growth and cultivation. In controlled environments, such as mushroom farms, creating conditions that support primordia development and pinhead formation is key to successful yields. Factors like substrate composition, humidity, and light exposure are carefully managed to mimic the natural conditions that trigger fruiting. By observing and supporting this stage, growers can ensure the healthy development of mushrooms from mycelium to mature fruiting bodies. This knowledge also highlights the resilience and adaptability of fungi, which thrive in diverse ecosystems by leveraging their mycelial networks and reproductive strategies.

Mastering Commercial Mushroom Cultivation: A Comprehensive Guide to Profitable Growth

You may want to see also

Sporocarp Maturation: Caps expand, gills release spores, completing the natural growth and reproduction cycle

As mushrooms progress through their natural growth cycle, they reach a critical stage known as sporocarp maturation. This phase is marked by the expansion of the mushroom caps, which serve as the primary structures for spore production and dispersal. The cap, initially small and tightly closed, gradually unfolds as the mushroom matures. This expansion is driven by the absorption of water and the growth of cells within the cap tissue. As the cap opens, it reveals the gills or pores located on the underside, which are essential for the next stage of reproduction.

The gills, composed of thin, blade-like structures, are the sites where spores are produced. Each gill contains numerous basidia, the specialized cells responsible for spore formation. As the cap expands, the gills become more exposed, allowing for efficient spore release. Within the basidia, spores develop through a process of meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in the offspring. Once mature, these spores are ready to be dispersed, but they remain attached to the basidia until environmental conditions trigger their release.

Spores are released through a combination of environmental cues and physical mechanisms. Factors such as humidity, air movement, and temperature play a crucial role in initiating spore discharge. When conditions are optimal, the basidia undergo rapid changes, causing the spores to be propelled into the air. This release mechanism ensures that spores are dispersed over a wide area, increasing the chances of colonization in new habitats. The gills, now having fulfilled their reproductive role, begin to dry out as the mushroom completes its life cycle.

The expansion of the cap and the subsequent release of spores from the gills are pivotal steps in the mushroom's natural growth and reproduction cycle. This process not only ensures the survival of the species but also contributes to the ecosystem by decomposing organic matter and recycling nutrients. Once spores are released, they can remain dormant in the soil or other substrates until favorable conditions allow them to germinate and grow into new mycelium, thus starting the cycle anew.

Completing the sporocarp maturation phase signifies the end of the mushroom's above-ground life cycle. After spore release, the mushroom begins to degrade, returning its nutrients to the environment. This decomposition is facilitated by the same mycelium network that initially supported the mushroom's growth. The cycle is inherently sustainable, as the mycelium continues to thrive underground, ready to produce new mushrooms when conditions are right. Through sporocarp maturation, mushrooms exemplify the efficiency and resilience of natural reproductive strategies.

Discovering Morel Mushrooms: Do They Thrive in Colorado's Forests?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms require a humid environment, organic matter (like decaying wood, leaves, or soil), and moderate temperatures. They thrive in shaded areas with good air circulation and sufficient moisture.

Mushrooms reproduce by releasing spores from their gills or pores. These spores are carried by wind, water, or animals to new locations, where they germinate and grow into new fungi if conditions are favorable.

Mushrooms do not require sunlight for growth, as they are not photosynthetic. Instead, they obtain nutrients by breaking down organic matter in their environment.

Mushrooms act as decomposers, breaking down dead plant and animal matter, which recycles nutrients back into the soil. They also form symbiotic relationships with plants, aiding in nutrient absorption and supporting forest health.

![Boomer Shroomer Inflatable Monotub Kit, Mushroom Growing Kit Includes a Drain Port, Plugs & Filters, Removeable Liner [Patent No: US 11,871,706 B2]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61K9zwzRQxL._AC_UL320_.jpg)