Myxococcus xanthus, a soil-dwelling bacterium, regulates spore formation through a complex interplay of environmental cues and intracellular signaling pathways. In response to nutrient depletion, Myxococcus cells initiate a multicellular developmental program, aggregating into fruiting bodies where a subset of cells differentiate into spores. This process is tightly controlled by the CsgA-CsgB signaling system, which senses starvation and activates the expression of developmental genes. Additionally, the FruA regulon plays a critical role in coordinating cell-to-cell communication via extracellular signals, ensuring synchronized differentiation. Environmental factors such as population density, detected through quorum sensing, further modulate spore formation. This highly regulated mechanism allows Myxococcus to survive harsh conditions, highlighting its adaptive strategies in dynamic ecosystems.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Environmental cues triggering sporulation

Myxococcus xanthus, a soil-dwelling bacterium, employs a sophisticated regulatory network to initiate spore formation in response to environmental stressors. One critical cue is nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of amino acids and carbon sources. When these resources become scarce, M. xanthus cells detect the change through signaling pathways involving c-di-GMP, a secondary messenger that accumulates under starvation conditions. Elevated c-di-GMP levels trigger the expression of genes essential for sporulation, such as those encoding sigma factors like SigC and SigB, which redirect the cell’s transcriptional machinery toward developmental processes. This nutrient-sensing mechanism ensures that sporulation occurs only when survival necessitates a dormant, resilient state.

Another environmental trigger is population density, monitored through a process known as quorum sensing. As M. xanthus cells aggregate in response to starvation, they secrete signaling molecules like A-factor, a fatty acid derivative. At high cell densities, A-factor accumulates to a threshold level, activating the intrisic transcription factor, which in turn promotes the expression of sporulation genes. This density-dependent regulation ensures that sporulation is synchronized across the population, maximizing the chances of survival through collective behavior. For researchers studying this phenomenon, mimicking high-density conditions in vitro by adjusting cell concentrations (e.g., 5x10^8 cells/mL) can induce sporulation more predictably.

Surface availability also plays a pivotal role in triggering sporulation. M. xanthus cells preferentially form spores on solid surfaces rather than in liquid environments, a behavior linked to the mechanical properties of the substrate. Studies have shown that cells on surfaces with higher stiffness (e.g., agar plates with 1.5% agar concentration) exhibit accelerated sporulation compared to softer substrates. This response is mediated by the cell’s ability to sense and respond to mechanical cues, likely through changes in cell shape and cytoskeletal dynamics. For experimental setups, using agar plates with varying stiffness can help elucidate the role of mechanical signals in sporulation.

Temperature shifts provide yet another environmental cue for sporulation in M. xanthus. While optimal growth occurs at 32°C, exposure to temperatures below 25°C or above 37°C can induce stress responses that promote spore formation. Cold stress, in particular, activates the cold-shock protein CspL, which interacts with RNA polymerase to upregulate developmental genes. Conversely, heat stress triggers the heat-shock response, leading to the production of protective proteins that indirectly support sporulation. Researchers can exploit these temperature sensitivities by subjecting cultures to controlled thermal shifts (e.g., 4°C for cold stress or 42°C for heat stress) to study their impact on sporulation kinetics.

Finally, desiccation stress serves as a potent environmental trigger for sporulation in M. xanthus. In natural soil habitats, fluctuating moisture levels expose cells to drying conditions, prompting the formation of spores as a protective measure. Experimental studies have demonstrated that subjecting cells to controlled desiccation (e.g., reducing humidity to 20% for 24 hours) significantly enhances spore yield. This response is mediated by the activation of osmotic stress pathways, which overlap with sporulation regulatory networks. For practical applications, simulating desiccation stress in laboratory settings can provide insights into the adaptive strategies of M. xanthus and inform biotechnological approaches to enhance spore production.

Are Spores the Most Electron-Dense Organic Material? Exploring Their Density

You may want to see also

Role of cell density in regulation

Cell density acts as a critical trigger for Myxococcus xanthus to initiate spore formation, a process known as fruiting body development. This bacterium, renowned for its social behavior, relies on a quorum sensing mechanism to gauge population density. As cells multiply and reach a certain threshold, they release signaling molecules called A-factor, a type of fatty acid derivative. The concentration of A-factor in the environment directly correlates with cell density, providing a reliable indicator of population size. This simple yet elegant system ensures that Myxococcus only commits to the energetically costly process of sporulation when a sufficient number of cells are present to increase the chances of survival.

Understanding the A-factor Threshold

The A-factor threshold required to trigger sporulation is not a fixed value but rather a range, typically falling between 10^7 and 10^8 cells per milliliter. Below this range, A-factor concentration remains too low to activate the necessary genetic pathways. Above this threshold, A-factor binds to specific receptors on the cell surface, initiating a signaling cascade that ultimately leads to the expression of genes involved in fruiting body formation. This density-dependent regulation prevents premature sporulation, which would be wasteful of resources and potentially detrimental to the population's survival.

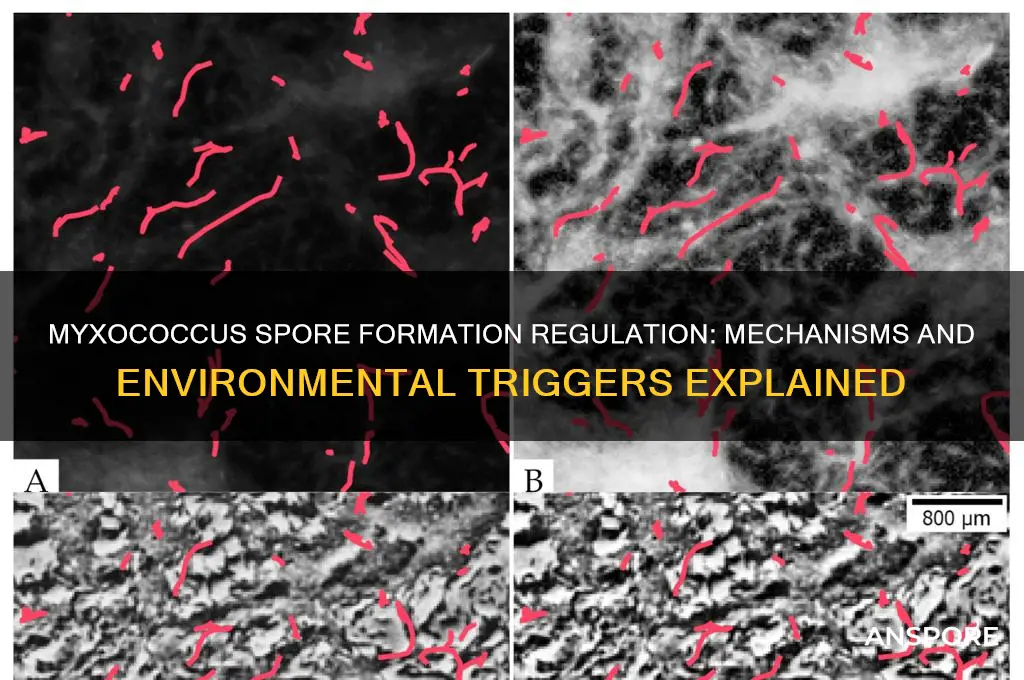

The Spatial Dimension: Cell Aggregation and Sporulation

Cell density regulation in Myxococcus is not solely about the number of cells in a given volume; it's also about their spatial arrangement. As A-factor concentration rises, cells begin to aggregate, forming dense clusters. This aggregation is crucial for efficient sporulation, as it facilitates cell-cell communication and the coordinated expression of genes required for fruiting body development. Within these aggregates, cells differentiate into distinct cell types, with only a subset ultimately forming spores. This spatial organization ensures that spores are produced in a protected environment, increasing their chances of survival during harsh conditions.

Practical Implications and Experimental Considerations

Understanding the role of cell density in Myxococcus sporulation has practical implications for laboratory studies. Researchers can manipulate cell density to control the timing and efficiency of sporulation. For instance, by adjusting the initial inoculum size or using growth media that promote or inhibit cell aggregation, scientists can study the effects of density on gene expression, cell differentiation, and spore formation. Additionally, knowledge of the A-factor threshold can be leveraged to develop novel strategies for controlling Myxococcus populations in environmental or industrial settings.

A Model for Social Behavior and Development

The density-dependent regulation of sporulation in Myxococcus serves as a fascinating example of how bacteria can coordinate complex behaviors through simple chemical signals. This system highlights the importance of cell-cell communication and population dynamics in microbial development. By studying Myxococcus, researchers gain insights into the fundamental principles governing bacterial sociality and its impact on survival strategies. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of microbial biology but also has potential applications in fields such as biotechnology and bioengineering, where controlling bacterial behavior is crucial.

Are Water Bottle Bacteria Spores Poisonous? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Genetic pathways controlling spore development

Myxococcus xanthus, a soil-dwelling bacterium, employs a sophisticated genetic regulatory network to control spore formation, a process critical for survival under nutrient-limited conditions. Central to this network is the fru (fruiting body) locus, a 60-kb region encoding over 70 genes involved in developmental signaling and sporulation. Among these, the csgA gene acts as a master regulator, initiating the developmental cascade by sensing starvation signals and activating downstream pathways. Mutations in csgA result in a complete block in spore formation, underscoring its pivotal role.

Downstream of csgA, the nla (no large spores) operon fine-tunes spore differentiation by controlling cell-type-specific gene expression. This operon ensures that only a subset of cells within the fruiting body differentiate into spores, while others remain as peripheral rods. The nla system integrates environmental cues, such as oxygen and nutrient availability, to modulate spore yield. For instance, overexpression of nla24 increases spore production by 30%, highlighting its role as a potential target for enhancing sporulation efficiency in biotechnological applications.

Another critical pathway involves the dev (development) genes, which coordinate cell-to-cell signaling during fruiting body formation. The devS-devR two-component system, in particular, responds to extracellular signals by phosphorylating response regulators that activate sporulation genes. Disruption of devR leads to aberrant fruiting body morphology and reduced spore viability, emphasizing its role in maintaining developmental integrity. Interestingly, the dev system shares homology with bacterial quorum sensing pathways, suggesting a conserved mechanism for coordinating collective behaviors.

Epigenetic regulation also plays a role in spore development, with DNA methylation and chromatin remodeling influencing gene accessibility. The mrp (methyltransferase-related protein) genes, for example, modify cytosine residues in promoter regions of sporulation genes, thereby controlling their transcriptional activity. Treatment with 5-azacytidine, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, reduces spore formation by 50%, illustrating the importance of epigenetic modifications in this process.

Practical applications of understanding these pathways include optimizing spore production for industrial uses, such as biocontrol agents or probiotics. For instance, manipulating csgA or nla24 expression levels through plasmid-based systems can enhance spore yield in bioreactors. However, caution must be exercised to avoid disrupting the delicate balance of the regulatory network, as overexpression of certain genes can lead to developmental defects. By dissecting these genetic pathways, researchers can harness Myxococcus’s sporulation mechanisms for both fundamental biology and applied biotechnology.

Exploring Jungle Spore Depths: Where and How Deep They Spawn

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nutrient availability impact on sporulation

Myxococcus xanthus, a soil-dwelling bacterium, employs a sophisticated regulatory network to control spore formation, a process intimately tied to nutrient availability. When nutrients become scarce, M. xanthus cells initiate a developmental program culminating in the formation of resilient spores. This response is not merely a passive reaction to starvation but a finely tuned strategy ensuring survival during adverse conditions.

Glucose, a primary energy source, plays a pivotal role in this regulation. Studies demonstrate that high glucose concentrations repress sporulation genes, diverting cellular resources towards growth and metabolism. Conversely, glucose depletion triggers a cascade of events, including the activation of key transcription factors like MrpC and FruA, which orchestrate the expression of genes essential for spore development.

Understanding this nutrient-sporulation link holds practical implications. In biotechnological applications, manipulating nutrient levels can control spore production in M. xanthus cultures. For instance, gradually reducing glucose concentration over 24-48 hours can induce synchronized sporulation, yielding a uniform population of spores for research or industrial purposes.

This nutrient-dependent regulation also sheds light on M. xanthus' ecological role. In its natural habitat, fluctuating nutrient availability dictates the balance between vegetative growth and spore formation, influencing population dynamics and survival strategies within microbial communities.

Further research into the specific molecular mechanisms linking nutrient sensing to sporulation pathways promises to unveil novel targets for controlling M. xanthus development. This knowledge could lead to advancements in biotechnology, environmental microbiology, and our understanding of bacterial survival strategies in diverse ecosystems.

Can Raw Hamburger Produce Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind Food Safety

You may want to see also

Cell-to-cell signaling in spore formation

Myxococcus xanthus, a soil-dwelling bacterium, employs a sophisticated cell-to-cell signaling mechanism to coordinate spore formation during times of starvation. This process, known as fruiting body development, is a remarkable example of bacterial social behavior. At the heart of this regulation lies the CsgA signaling system, a cell-to-cell communication pathway that ensures synchronized sporulation.

When nutrients become scarce, M. xanthus cells initiate a series of events culminating in the formation of spore-filled fruiting bodies. This process is not a solitary endeavor; it requires precise coordination among thousands of cells. The CsgA system acts as the molecular language facilitating this communication.

Imagine a crowded room where individuals need to coordinate their actions without direct physical contact. They rely on whispers and gestures to convey information. Similarly, M. xanthus cells secrete and detect signaling molecules, primarily A-signal and C-signal, to gauge population density and environmental conditions. A-signal, a short oligopeptide, is produced and secreted by cells, diffusing through the population. As the concentration of A-signal increases, it binds to receptors on neighboring cells, triggering a cascade of intracellular events. This signal acts as a quorum-sensing mechanism, informing cells about the size of the population and the urgency to initiate sporulation.

C-signal, on the other hand, is a lipid-derived molecule that plays a crucial role in directing cell movement during fruiting body formation. It acts as a chemoattractant, guiding cells towards aggregation centers where sporulation occurs. This coordinated movement, akin to a bacterial march, ensures that cells assemble into the characteristic mound-like structures of fruiting bodies.

The interplay between A-signal and C-signal is a delicate dance, finely tuned to environmental cues. As starvation persists, the concentration of these signals increases, amplifying the response and driving cells towards irreversible commitment to sporulation. This multi-layered signaling network ensures that spore formation is a collective effort, maximizing the chances of survival for the population. Understanding these intricate cell-to-cell communication pathways not only sheds light on the remarkable social behavior of M. xanthus but also provides valuable insights into the fundamental principles of bacterial development and survival strategies.

Are Laccaria Spores White? Unveiling the Truth About Their Color

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spore formation in Myxococcus is triggered by environmental stress, such as nutrient depletion. When resources become scarce, cells aggregate into a multicellular structure called a fruiting body, within which spores develop.

Myxococcus uses quorum sensing, a cell-to-cell signaling mechanism, to regulate spore formation. The C-signal, a small molecule, coordinates the aggregation and differentiation of cells into spores during fruiting body development.

The CsgA protein is a key regulator of spore formation in Myxococcus. It acts as a transcription factor that activates genes involved in sporulation, ensuring proper differentiation of cells into spores within the fruiting body.

Myxococcus ensures only a subset of cells differentiate into spores through spatial organization within the fruiting body. Cells at the top of the structure differentiate into spores, while those at the base remain as vegetative cells, facilitated by differential gene expression and signaling.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)