Propagation by spores is a unique and efficient method of reproduction employed by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria. Unlike seeds, spores are microscopic, unicellular structures that are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions, allowing them to survive in dormant states for extended periods. When conditions become favorable—such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrients—spores germinate, developing into new individuals. In plants like ferns and mosses, spores are produced in specialized structures and dispersed by wind or water, ensuring widespread colonization. Fungi, such as mushrooms, release spores from gills or pores, which can travel vast distances to establish new colonies. This method of propagation enables rapid dispersal and colonization of diverse habitats, making spores a vital mechanism for the survival and proliferation of many species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method | Asexual reproduction |

| Organisms | Fungi, bacteria, plants (ferns, mosses), some algae |

| Spore Types | Sporangiospores, conidia, zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores |

| Formation | Produced in specialized structures (sporangia, conidiophores, etc.) |

| Dispersal | Wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms (e.g., puffballs) |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods under unfavorable conditions |

| Germination | Requires suitable environmental conditions (moisture, temperature, light) |

| Advantages | High dispersal ability, survival in harsh environments, rapid colonization |

| Examples | Ferns (produce spores), mushrooms (basidiospores), bread mold (conidia) |

| Significance | Key to ecosystem functions like decomposition and nutrient cycling |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Spores develop within sporangia via meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity and survival in harsh conditions

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, or explosive release aid spores in traveling to new environments for growth

- Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant, resisting extreme temperatures, dryness, and other adverse conditions until optimal growth occurs

- Germination Process: Favorable conditions trigger spore activation, leading to emergence of the initial growth structure (prothallus)

- Advantages Over Seeds: Spores require no pollinators, reproduce rapidly, and thrive in diverse, often challenging environments efficiently

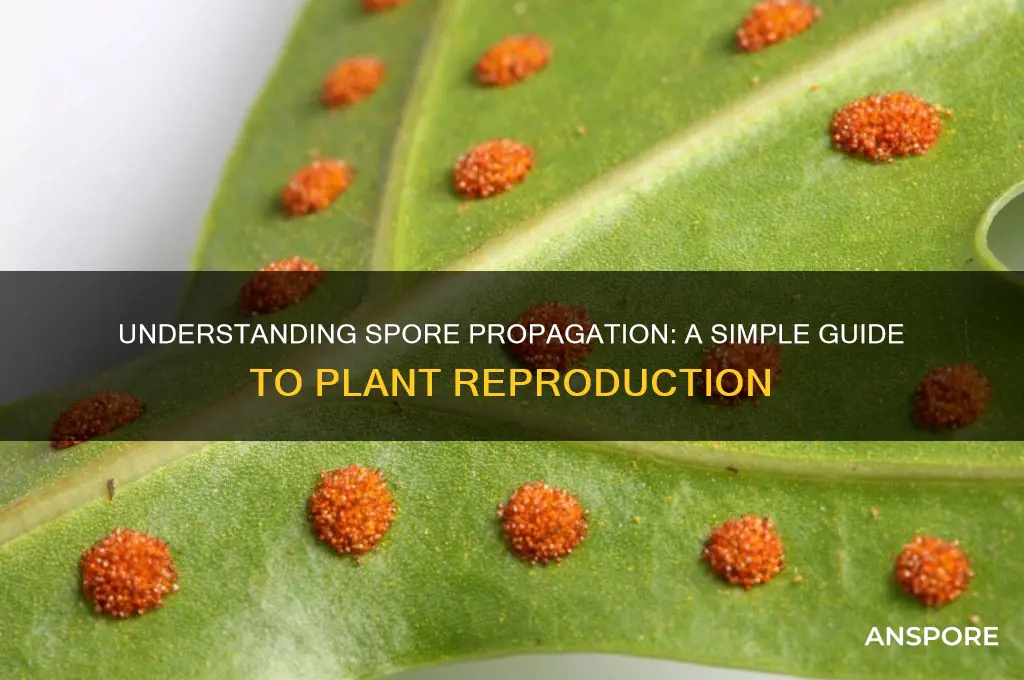

Spore Formation: Spores develop within sporangia via meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity and survival in harsh conditions

Spores are nature’s survival capsules, engineered to endure extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. Within the protective walls of sporangia, these microscopic structures undergo meiosis, a process that not only reduces the chromosome number but also shuffles genetic material through recombination. This mechanism ensures that each spore carries a unique genetic blueprint, enhancing the species’ ability to adapt to unpredictable environments. For example, ferns release spores that can lie dormant for years, waiting for the right conditions to germinate, while fungi like *Aspergillus* use spores to colonize new habitats rapidly.

To understand spore formation, imagine a factory line where each unit is designed for resilience. Meiosis begins with a diploid cell within the sporangium, which divides twice to produce four haploid spores. This reduction in chromosome number is critical, as it allows for genetic diversity when spores later fuse during fertilization. The sporangium itself acts as a protective incubator, shielding the developing spores from desiccation, UV radiation, and predators. In plants like mosses, sporangia are often elevated on stalks to aid in spore dispersal, while in fungi, they may be embedded in fruiting bodies like mushrooms.

Practical applications of spore formation extend beyond biology classrooms. Gardeners, for instance, can harness this process by collecting fern spores in late summer, storing them in airtight containers, and sowing them on damp soil in spring. Similarly, mushroom cultivators inoculate substrates with fungal spores, ensuring genetic diversity in their crops. However, caution is necessary: spores are lightweight and easily dispersed, so handling them in enclosed spaces can lead to contamination. Always wear gloves and masks when working with spores, especially those from fungi, which can cause allergies or infections.

Comparatively, spore formation contrasts sharply with vegetative propagation, which clones plants without genetic variation. While cuttings from a parent plant produce identical offspring, spores introduce diversity, making populations more resilient to diseases and environmental changes. This is why spore-producing organisms like ferns and fungi thrive in diverse ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to arid deserts. By studying spore formation, scientists gain insights into evolutionary strategies, while hobbyists and professionals alike can apply this knowledge to horticulture, mycology, and conservation efforts.

In conclusion, spore formation within sporangia via meiosis is a masterclass in survival and adaptation. It combines genetic recombination with physical protection, ensuring that species not only endure but thrive in harsh conditions. Whether you’re a gardener cultivating rare ferns or a researcher studying fungal ecosystems, understanding this process unlocks practical and theoretical benefits. By mimicking nature’s design, we can propagate plants and fungi more effectively, preserving biodiversity for future generations.

Can You Safely Dispose of Fungal Spores Down the Drain?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, or explosive release aid spores in traveling to new environments for growth

Spores, those microscopic marvels of survival, rely on a variety of dispersal mechanisms to reach new habitats. Wind, the most common agent, whisks spores aloft in a chaotic dance, carrying them across vast distances. Ferns and mushrooms exemplify this strategy, releasing millions of spores into the air, ensuring at least a few land in fertile ground. This passive method, while indiscriminate, maximizes reach, allowing species to colonize diverse environments, from forest floors to mountain peaks.

Water, another key player, offers a more directed journey for spores. Aquatic plants like mosses and certain algae release spores into streams or ponds, where currents act as highways to new locations. This method is particularly effective in humid or aquatic ecosystems, where water’s presence is constant. For instance, the spores of *Pilobolus*, a fungus, are launched with explosive force toward nearby water sources, showcasing how water can be both a medium and a target for dispersal.

Animals, often unwitting accomplices, aid spore dispersal through their movements. Burdock seeds, though not spores, illustrate this concept: their hooked structures attach to fur, later detaching in new areas. Similarly, spores of certain fungi cling to insect exoskeletons or bird feathers, hitching rides to distant locales. This symbiotic relationship benefits both parties—animals gain no harm, while spores secure transport to nutrient-rich environments, such as animal nesting sites or dung deposits.

Explosive release, a dramatic mechanism, propels spores with force, ensuring they travel farther than passive methods allow. The "gunpowder fungus" (*Pilobolus*) exemplifies this, using internal pressure to eject spores up to 2 meters away. Such precision increases the likelihood of landing in favorable conditions, often near decaying organic matter where fungi thrive. This method, while energy-intensive, guarantees targeted dispersal, a strategy particularly useful in dense or competitive habitats.

Each dispersal mechanism—wind, water, animals, or explosive release—serves a unique purpose, tailored to the spore’s environment and survival needs. Wind maximizes coverage, water ensures directed movement, animals provide access to specific niches, and explosive release combines precision with distance. Together, these strategies highlight the ingenuity of nature, ensuring spores not only survive but thrive in new environments, perpetuating their species across generations.

Breathing in Spores: Unraveling Dizziness, Nausea, and Breathing Difficulties

You may want to see also

Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant, resisting extreme temperatures, dryness, and other adverse conditions until optimal growth occurs

Spores are nature's ultimate survival capsules, engineered to endure conditions that would annihilate most life forms. Encased in a protective wall, they can withstand temperatures ranging from -20°C to 100°C, desiccation levels as low as 1% relative humidity, and even the vacuum of space. This resilience is not passive; it’s an active state of dormancy, a metabolic pause that allows spores to persist for centuries, waiting for the precise combination of moisture, warmth, and nutrients to trigger germination. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores have been revived after 10,000 years in permafrost, showcasing their unparalleled ability to bridge time and adversity.

Consider the practical implications of this dormancy for gardeners and farmers. Spores of beneficial fungi like *Trichoderma* can be stored in dry, cool conditions for years, retaining viability until applied to soil. To maximize survival, store spore-based products in airtight containers at temperatures below 20°C, avoiding exposure to light and humidity. When conditions improve—say, after a rain event or irrigation—these spores spring to life, colonizing roots and protecting plants from pathogens. This strategic use of dormancy turns spores into a time-released biological resource, ensuring their presence when most needed.

The mechanism behind spore dormancy is a marvel of evolutionary engineering. During sporulation, cells synthesize dipicolinic acid, a molecule that binds calcium ions to stabilize DNA and proteins against heat and dryness. Simultaneously, the spore coat hardens, forming a barrier impermeable to most toxins and enzymes. This dual defense system explains why spores can survive autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, a process that kills virtually all other life forms. For industries like food preservation and healthcare, understanding this mechanism is critical for both harnessing and combating spore-forming organisms.

Comparing spore dormancy to seed dormancy highlights its uniqueness. While seeds rely on internal chemical signals and external environmental cues to break dormancy, spores require only the restoration of favorable conditions. Seeds often need specific triggers like cold stratification or scarification, but spores are more opportunistic, germinating within hours of moisture availability. This simplicity makes spores ideal for rapid colonization in unpredictable environments, such as after a forest fire or in newly exposed soil. For conservationists, this means spore-based restoration efforts can be timed to coincide with natural wetting events for maximum impact.

Finally, the survival strategies of spores offer lessons in resilience applicable beyond biology. Their ability to pause life, conserve resources, and wait for optimal conditions is a metaphor for sustainable living. In agriculture, incorporating spore-forming microorganisms into soil amendments can create a reservoir of dormant allies, ready to activate during stress periods like drought or pest outbreaks. For hobbyists, cultivating spore-based cultures requires patience and precision—monitor humidity levels above 80% and temperatures around 25°C to encourage germination. By mimicking nature’s timing, we can harness spores’ dormancy to build ecosystems that thrive in adversity.

Are Spore Syringes Legal in the UK? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Process: Favorable conditions trigger spore activation, leading to emergence of the initial growth structure (prothallus)

Spores, often likened to the plant world's version of seeds, remain dormant until conditions align for survival and growth. This dormancy is a survival mechanism, ensuring that energy is conserved until the environment can support life. When favorable conditions—such as adequate moisture, temperature, and light—are met, the spore's metabolic processes awaken, marking the beginning of germination. This activation is not random but a precise response to environmental cues, a testament to the spore's evolutionary sophistication.

The germination process is a delicate dance of biology and environment. For instance, in ferns, spores require a humid substrate and temperatures between 18–25°C (64–77°F) to initiate growth. Once activated, the spore absorbs water, swelling and rupturing its protective outer layer. This allows the emergence of the prothallus, a small, heart-shaped structure that serves as the initial growth stage. The prothallus is not just a transitional phase but a fully functional organism capable of photosynthesis, albeit on a miniature scale.

To foster this process, gardeners and botanists can replicate these conditions. Start by preparing a sterile, moisture-retentive medium like peat moss or vermiculite. Maintain humidity by covering the container with a clear lid or plastic wrap, ensuring the temperature remains within the optimal range. Light is also critical; spores typically require indirect light to germinate, so avoid direct sunlight. Patience is key, as germination can take weeks, depending on the species.

Comparatively, spore germination differs from seed germination in its reliance on external conditions rather than internal energy reserves. While seeds often contain stored nutrients, spores must immediately establish a photosynthetic capability via the prothallus. This makes the prothallus a critical link in the lifecycle, bridging the gap between dormancy and mature plant development. Its success hinges on the environment’s consistency, underscoring the importance of controlled conditions in cultivation.

In practical terms, understanding this process allows for the successful propagation of spore-bearing plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. For example, to grow ferns from spores, scatter them evenly on the surface of a moist medium, press them gently to ensure contact, and maintain high humidity. The emergence of prothalli signals success, and from these, new fern plants will eventually develop. This method not only preserves biodiversity but also offers a rewarding glimpse into the intricate mechanisms of plant reproduction.

Can Cultures Accurately Detect C. Diff Spores in Clinical Settings?

You may want to see also

Advantages Over Seeds: Spores require no pollinators, reproduce rapidly, and thrive in diverse, often challenging environments efficiently

Spores bypass the need for pollinators, a critical advantage over seed-based reproduction. Unlike seeds, which rely on external agents like wind, water, or animals for fertilization and dispersal, spores are self-sufficient. This independence allows spore-producing organisms, such as ferns and fungi, to colonize environments where pollinators are scarce or absent, such as dense forests, underwater ecosystems, or nutrient-poor soils. For example, mosses thrive in Arctic tundra regions where flowering plants struggle due to the lack of insect pollinators. This autonomy ensures survival in isolation, making spores a reliable reproductive strategy in ecologically challenging conditions.

The rapid reproduction rate of spores outpaces that of seeds, enabling quick colonization of new or disturbed habitats. A single spore can germinate within hours under favorable conditions, whereas seeds often require days or weeks to sprout. Fungi, for instance, release millions of spores in a single dispersal event, ensuring at least some find suitable environments to grow. This efficiency is particularly evident in post-fire ecosystems, where spore-producing plants like certain ferns and mushrooms are among the first to appear, stabilizing soil and preparing the ground for slower-growing seed plants. For gardeners or restoration ecologists, this means spore-based propagation can accelerate revegetation efforts in degraded areas.

Spores’ adaptability to diverse and harsh environments is unparalleled. Unlike seeds, which often require specific conditions like consistent moisture, warmth, or light to germinate, spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for the right moment to activate. This resilience is exemplified by tardigrades, which can survive extreme temperatures, radiation, and even the vacuum of space, partly due to their spore-like resting stages. In practical terms, this means spores can be used in agricultural or landscaping projects in unpredictable climates, reducing the risk of crop failure. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi spores can enhance soil health in arid regions where traditional seed-based methods might fail.

The efficiency of spore propagation lies in its minimal resource requirements. Spores are lightweight, microscopic, and often produced in vast quantities, allowing for widespread dispersal with minimal energy investment from the parent organism. In contrast, seeds are larger, nutrient-dense, and require more resources to produce, limiting the number that can be generated. This makes spores ideal for organisms in nutrient-poor environments, such as lichens growing on bare rock. For hobbyists or professionals cultivating spore-based organisms, this efficiency translates to lower costs and higher success rates. A single spore culture can yield thousands of new individuals with minimal maintenance, making it a cost-effective method for projects ranging from mushroom farming to laboratory research.

Understanding Spore Formation: A Survival Mechanism in Microorganisms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Propagation by spore is a method of asexual reproduction in plants, fungi, and some bacteria, where new individuals are produced from single-celled structures called spores. These spores are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions and can remain dormant for extended periods before germinating under favorable conditions.

In plants, spores typically form in specialized structures such as sporangia. For example, in ferns, sporangia are located on the undersides of fronds. Within these structures, cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores, which are then released into the environment.

Spore germination requires specific environmental conditions, including adequate moisture, appropriate temperature, and sometimes light. Once these conditions are met, the spore absorbs water, activates its metabolic processes, and begins to grow into a new organism.

Propagation by spore allows organisms to survive in unfavorable conditions, disperse over long distances, and rapidly colonize new habitats. Spores are lightweight and can be carried by wind, water, or animals, enabling widespread distribution. Additionally, their resistance to extreme conditions ensures the survival of the species.

Fungi (e.g., mushrooms, molds), ferns, mosses, and some bacteria (e.g., Bacillus) commonly use spore propagation. In plants, this method is prevalent in non-seed plants like ferns and bryophytes, while fungi rely heavily on spores for reproduction and dispersal.