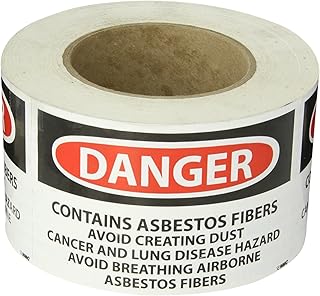

Asbestos, a group of naturally occurring minerals once widely used in construction and manufacturing, poses significant health risks when its microscopic fibers become airborne and inhaled. A common question surrounding asbestos exposure is how long these fibers, often referred to as spores (though technically they are fibers), remain suspended in the air. The duration asbestos fibers stay airborne depends on various factors, including fiber size, air currents, and environmental conditions. Smaller fibers can remain suspended for hours or even days, while larger particles may settle more quickly. Understanding this persistence is crucial, as prolonged exposure to airborne asbestos fibers can lead to severe health issues, such as lung cancer, mesothelioma, and asbestosis. Proper containment, ventilation, and professional removal are essential to minimize the risk of inhalation and ensure a safe environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time Asbestos Fibers Stay in Air | Can remain suspended for 48-72 hours or longer, depending on size |

| Fiber Size Influence | Smaller fibers (<5 μm) stay airborne longer than larger fibers |

| Air Movement Impact | Air currents, ventilation, or disturbances can resuspend settled fibers |

| Settling Time | Most fibers settle within 10-72 hours, but smaller fibers may persist |

| Environmental Factors | Humidity, temperature, and air pressure affect settling time |

| Indoor vs. Outdoor | Fibers persist longer indoors due to reduced air movement |

| Health Risk Duration | Prolonged exposure to airborne fibers increases risk of asbestos-related diseases |

| Detection Method | Air sampling and phase contrast microscopy (PCM) used to measure fiber concentration |

| Regulatory Threshold | OSHA permits 0.1 fibers per cubic centimeter (f/cc) over 8 hours |

| Resuspension Risk | Fibers can become airborne again if disturbed (e.g., sweeping, drilling) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Asbestos fiber size and weight affect airborne duration

- Environmental factors like air currents impact spore persistence

- Indoor vs. outdoor asbestos spore settling times differ

- Disturbance of asbestos materials increases airborne exposure risks

- Proper ventilation reduces asbestos fiber airborne longevity

Asbestos fiber size and weight affect airborne duration

Asbestos fibers, unlike spores, are microscopic, needle-like particles that can remain suspended in air for hours or even days, depending on their size and weight. Smaller, lighter fibers, typically measuring less than 3 micrometers in length and 0.5 micrometers in diameter, can stay airborne for extended periods, increasing the risk of inhalation. These minute particles are easily inhaled and can penetrate deep into the lungs, causing serious health issues such as asbestosis, lung cancer, and mesothelioma. In contrast, larger, heavier fibers settle more quickly, reducing their airborne duration and potential for inhalation.

Consider the practical implications of fiber size in real-world scenarios. During asbestos removal or disturbance, fibers released into the air with a size range of 1-5 micrometers are more likely to remain suspended, posing a significant risk to workers and occupants. For instance, in a poorly ventilated area, these fibers can accumulate, increasing the concentration of airborne asbestos and the likelihood of exposure. To mitigate this risk, it is essential to use proper personal protective equipment (PPE), such as respirators with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, and to ensure adequate ventilation during asbestos-related work.

The weight of asbestos fibers also plays a critical role in determining their airborne duration. Lighter fibers, with densities ranging from 2.4 to 3.4 grams per cubic centimeter, are more prone to remaining suspended in air due to their lower settling velocity. This is particularly concerning in environments where asbestos-containing materials (ACMs) are friable, meaning they can be easily crumbled or reduced to powder by hand pressure, releasing a high concentration of lightweight fibers. In such cases, implementing engineering controls, such as containment barriers and negative air pressure systems, can help minimize fiber release and reduce airborne duration.

A comparative analysis of fiber size and weight reveals that the most hazardous asbestos fibers are those that are both small and lightweight. Chrysotile, the most common type of asbestos, has fibers that are generally finer and more flexible than other types, such as amosite or crocidolite. This makes chrysotile fibers more likely to remain airborne and be inhaled, increasing the risk of asbestos-related diseases. For example, a study found that chrysotile fibers with a length-to-diameter ratio greater than 3:1 and a diameter less than 0.25 micrometers can remain airborne for up to 48 hours in a controlled environment.

To minimize the risks associated with airborne asbestos fibers, follow these practical tips: first, conduct regular inspections and assessments of ACMs in buildings constructed before the 1980s. Second, hire licensed asbestos professionals for removal or remediation projects, ensuring they adhere to strict safety protocols. Third, improve indoor air quality by using air purifiers with HEPA filters and maintaining proper ventilation. Lastly, educate workers and occupants about the risks of asbestos exposure and the importance of avoiding activities that may disturb ACMs. By understanding the relationship between asbestos fiber size, weight, and airborne duration, you can take proactive steps to protect yourself and others from the dangers of asbestos exposure.

Uninstalling Spore: What Happens to Your Creations? Find Out Now

You may want to see also

Environmental factors like air currents impact spore persistence

Asbestos fibers, once airborne, are subject to environmental forces that dictate their persistence and dispersal. Air currents, in particular, play a pivotal role in this process. Unlike spores from biological sources, asbestos fibers are inorganic and do not degrade over time. Instead, their airborne duration is influenced by physical factors such as air movement, particle size, and environmental conditions. For instance, fibers smaller than 5 micrometers can remain suspended for hours or even days, especially in still air. However, even slight air currents can accelerate their movement, either settling them onto surfaces or carrying them over greater distances. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for assessing exposure risks in both indoor and outdoor environments.

Consider the practical implications of air currents in a real-world scenario, such as a construction site where asbestos-containing materials are disturbed. In an open area with moderate wind speeds (5–10 mph), fibers can be transported hundreds of feet, increasing the risk of inhalation for workers and bystanders alike. Conversely, in an enclosed space with poor ventilation, fibers may remain suspended longer due to reduced air exchange, posing a prolonged hazard. OSHA guidelines recommend maintaining air movement below 200 feet per minute during asbestos abatement to minimize fiber dispersal, but even controlled environments are susceptible to unpredictable currents. This highlights the need for continuous air monitoring and containment strategies tailored to specific conditions.

From a comparative perspective, the persistence of asbestos fibers in air currents contrasts sharply with that of organic spores, such as mold or pollen. Organic spores degrade over time due to biological processes, whereas asbestos fibers remain structurally intact indefinitely. This distinction underscores the heightened risk associated with asbestos exposure, as even brief encounters with airborne fibers can lead to long-term health issues like asbestosis or mesothelioma. For example, a single fiber inhaled into the lungs can remain there for decades, causing chronic inflammation and tissue damage. Thus, managing air currents to limit fiber dispersal is not just a matter of containment but a critical health intervention.

To mitigate the impact of air currents on asbestos fiber persistence, proactive measures are essential. In indoor settings, HEPA filtration systems can capture fibers and prevent recirculation, while negative air pressure units contain contamination during removal activities. Outdoors, windbreaks or barriers can be employed to reduce fiber drift, particularly in residential areas near construction sites. Individuals working in high-risk environments should wear respirators with N100 filters, which block at least 99.97% of particles 0.3 micrometers or larger. Regular air quality testing, especially after disturbances, ensures that fiber concentrations remain below the EPA’s threshold of 0.01 fibers per cubic centimeter. By addressing air currents systematically, the risks associated with airborne asbestos can be significantly reduced.

Does Traizicide Include Milky Spore? A Comprehensive Ingredient Analysis

You may want to see also

Indoor vs. outdoor asbestos spore settling times differ

Asbestos spores, or fibers, behave differently in indoor and outdoor environments, primarily due to variations in air circulation, particle size, and surface interaction. Outdoors, asbestos fibers are subject to natural dispersion mechanisms like wind and rain, which can dilute and settle them more rapidly. For instance, fine asbestos particles (less than 1 micron) may remain suspended for hours or even days in still air, but wind can accelerate their deposition onto surfaces or into soil within minutes to hours. In contrast, indoor environments often lack such dispersion forces, causing fibers to remain airborne longer—sometimes for several days—unless actively removed by filtration or settling.

Analytical Insight: The settling time of asbestos fibers is influenced by their aerodynamic diameter. Indoors, where air movement is minimal, fibers larger than 5 microns settle within 10 minutes to 2 hours, while smaller fibers (<1 micron) can remain suspended for up to 48 hours. Outdoors, the presence of turbulence reduces these times significantly; even fine fibers typically settle within 1–6 hours due to wind and gravitational forces. This disparity highlights the importance of ventilation systems indoors to mitigate prolonged exposure risks.

Practical Tip: To reduce indoor asbestos fiber suspension, use HEPA filters in HVAC systems or portable air purifiers. Avoid activities like sweeping or vacuuming without a HEPA filter, as these can re-suspend fibers. Outdoors, wetting asbestos-containing materials before handling prevents fiber release, as moisture weighs down particles, causing them to settle faster.

Comparative Perspective: While outdoor environments naturally clear asbestos fibers more efficiently, indoor spaces pose a higher risk due to prolonged fiber suspension and repeated exposure. For example, a single disturbance of asbestos-containing insulation indoors can release fibers that remain airborne for days, increasing cumulative exposure. Outdoors, the same disturbance might release fibers, but they disperse and settle quickly, reducing the likelihood of repeated inhalation.

Takeaway: Understanding these settling time differences is critical for risk management. Indoor environments require proactive measures like air filtration and controlled handling of asbestos materials, while outdoor settings benefit from natural dispersion but still demand precautions to prevent initial fiber release. Tailoring mitigation strategies to the environment can significantly reduce asbestos exposure risks.

Does the Moon Have Purple Spores? Unraveling Lunar Mysteries

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$22.95 $24.95

Disturbance of asbestos materials increases airborne exposure risks

Asbestos fibers, when disturbed, can remain suspended in the air for hours to days, depending on factors like particle size, air currents, and ventilation. Unlike spores, which are biological entities, asbestos fibers are mineral-based and do not degrade over time. This means that once released, they persist in the environment, posing a cumulative risk with repeated exposure. Disturbing asbestos-containing materials (ACMs) through activities like drilling, sanding, or demolition is the primary mechanism by which these fibers become airborne, significantly increasing the risk of inhalation.

Consider a scenario where a homeowner decides to renovate a 1950s house with asbestos-containing insulation. Without proper precautions, cutting into the material releases millions of microscopic fibers into the air. These fibers, invisible to the naked eye, can travel throughout the home, settling on surfaces or remaining airborne. A single disturbance like this can elevate fiber concentrations in the air to dangerous levels, often exceeding the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) permissible exposure limit of 0.1 fibers per cubic centimeter over an 8-hour period. For bystanders, especially children or elderly individuals with developing or compromised respiratory systems, even brief exposure can lead to long-term health risks, including asbestosis or mesothelioma.

To mitigate these risks, it’s critical to follow specific protocols when dealing with ACMs. First, identify potential asbestos-containing materials through professional testing before beginning any work. If asbestos is present, avoid DIY removal and hire licensed abatement professionals who use HEPA filtration and containment barriers to minimize fiber release. For minor disturbances, such as repairing damaged asbestos tiles, wet the material to suppress dust and wear a respirator rated for asbestos (e.g., N95 or higher). After work is completed, conduct air quality testing to ensure fiber levels are safe, typically below 0.01 fibers per cubic centimeter, the threshold recommended by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for reoccupancy.

Comparing undisturbed ACMs to disturbed ones highlights the stark difference in risk. Intact asbestos materials, such as floor tiles or pipe insulation, pose minimal threat as long as they remain undisturbed. However, once damaged or manipulated, they become a silent hazard. For instance, a study found that drilling into asbestos-containing drywall increased airborne fiber concentrations by over 500 times compared to baseline levels. This underscores the importance of treating all ACMs with caution, even if they appear stable, and reinforces the principle that prevention is far safer—and cheaper—than remediation.

In conclusion, the disturbance of asbestos materials is a critical factor in airborne exposure risks, transforming a latent danger into an immediate threat. Understanding the persistence of asbestos fibers in the air and implementing proactive measures can drastically reduce health risks. Whether you’re a homeowner, contractor, or facility manager, treating ACMs with respect and adhering to safety guidelines is not just a best practice—it’s a necessity to protect yourself and others from the invisible yet enduring hazard of asbestos.

Are Milky Spores Organic? Unveiling the Truth for Gardeners

You may want to see also

Proper ventilation reduces asbestos fiber airborne longevity

Asbestos fibers, once disturbed, can remain suspended in the air for hours to days, posing a significant health risk through inhalation. Proper ventilation is a critical strategy to minimize this airborne longevity, reducing the concentration of fibers and mitigating exposure risks. By facilitating the dilution and removal of contaminated air, effective ventilation systems play a pivotal role in safeguarding indoor environments.

Analyzing the mechanics of ventilation reveals its dual function: introducing fresh outdoor air while expelling contaminated indoor air. In spaces where asbestos-containing materials (ACMs) are present or disturbed, such as during renovation or demolition, ventilation systems must be designed to operate at higher capacities. For instance, using negative air pressure units with HEPA filters can prevent fibers from migrating to unaffected areas. Research indicates that without adequate ventilation, asbestos fiber concentrations can remain elevated for up to 72 hours, whereas proper airflow reduces this duration to as little as 4–6 hours, depending on the system’s efficiency.

Implementing proper ventilation requires a systematic approach. First, assess the space to determine the optimal placement of exhaust fans and air intakes, ensuring a continuous flow of air from clean to potentially contaminated areas. Second, use portable air scrubbers with HEPA filters in localized zones where ACMs are handled. Third, maintain a minimum of 6–8 air changes per hour in enclosed spaces to effectively dilute fiber concentrations. For example, in a 1,000 cubic foot room, this translates to moving 6,000–8,000 cubic feet of air per hour. Caution must be taken to avoid recirculating contaminated air, as this can exacerbate exposure risks.

Comparatively, spaces with poor ventilation not only prolong asbestos fiber suspension but also increase the likelihood of accumulation on surfaces, necessitating more extensive decontamination efforts. In contrast, well-ventilated areas not only reduce airborne fiber longevity but also lower the overall fiber load, decreasing the risk of long-term health issues like asbestosis or mesothelioma. A study in occupational settings found that workers in properly ventilated environments had fiber exposure levels 50–70% lower than those in poorly ventilated spaces.

Practically, homeowners and contractors can adopt simple yet effective measures. For DIY projects involving ACMs, open windows and use box fans to create a cross-breeze, directing air outward. In larger-scale operations, consult HVAC professionals to design systems tailored to the specific demands of asbestos mitigation. Regularly inspect and maintain ventilation equipment to ensure optimal performance, as clogged filters or malfunctioning fans can undermine their effectiveness. By prioritizing ventilation, individuals can significantly reduce the time asbestos fibers remain airborne, creating safer environments for all occupants.

Transferring JPEGs Safely from a PC Infected with Spora Ransomware

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Asbestos fibers can remain suspended in the air for hours or even days, depending on factors like fiber size, air currents, and ventilation.

Yes, asbestos fibers can become airborne again if disturbed, such as through sweeping, vacuuming, or walking on contaminated surfaces.

Smaller asbestos fibers may take several hours to days to settle, while larger fibers settle more quickly, often within minutes to hours.

Yes, using HEPA filtration systems can significantly reduce the time asbestos fibers remain airborne by capturing them and preventing recirculation.