Growing mushrooms from spores to a fully colonized monotub involves several stages, each with its own timeline. The process begins with spore germination, which typically takes 2 to 7 days under optimal conditions. Once germinated, the mycelium grows and colonizes the substrate, a phase that can last 2 to 4 weeks depending on factors like temperature, humidity, and substrate quality. After full colonization, the substrate is transferred to a monotub, where fruiting conditions are established. Fruiting bodies (mushrooms) usually begin to form within 7 to 14 days, though this can vary based on the mushroom species and environmental conditions. Overall, the entire process from spore to harvest in a monotub can take anywhere from 6 to 10 weeks, making it a rewarding but time-intensive endeavor.

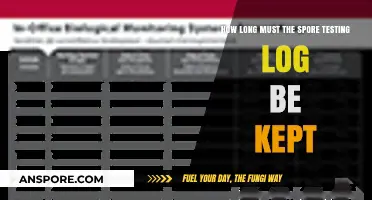

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore to Colonization (Agar) | 7-14 days (depending on mushroom species and conditions) |

| Agar to Grain Spawn | 10-21 days (time for mycelium to fully colonize grain spawn) |

| Grain Spawn to Bulk Substrate | 7-14 days (time for mycelium to colonize bulk substrate in monotub) |

| Total Time (Spore to Monotub) | 24-49 days (sum of all stages, varies by species and environment) |

| Optimal Temperature Range | 70-75°F (21-24°C) for most mushroom species |

| Humidity Requirement | 90-95% during colonization and fruiting stages |

| Light Requirement | Indirect light (not critical for colonization, needed for fruiting) |

| Common Mushroom Species | Oyster, Lion's Mane, Golden Teacher (Psilocybe), Reishi, etc. |

| Key Factors Affecting Time | Temperature, humidity, spore viability, substrate quality, and strain |

| Monotub Setup Time | 1-2 days (preparation and sterilization of bulk substrate) |

| Fruiting Time After Monotub | 7-14 days (time for mushrooms to grow after pinning) |

Explore related products

$15.63

What You'll Learn

Optimal Conditions for Spore Germination

Spore germination is the critical first step in the journey from spore to monotub, and its success hinges on creating an environment that mimics the spore’s natural triggers for activation. Spores, by design, are dormant and resilient, waiting for specific conditions to signal safety and nutrient availability. To awaken them, maintain a temperature range of 70–75°F (21–24°C), as this mirrors the warm, humid environments where fungi thrive. Light exposure, though not strictly necessary, can accelerate germination; a few hours of indirect light daily can stimulate activity. The substrate should be sterile and nutrient-rich, with a pH level between 5.5 and 6.5, as spores are sensitive to acidity. These conditions, when precisely controlled, reduce germination time from days to mere hours, setting the stage for rapid colonization.

Consider the hydration process as a delicate balance between drowning and dehydration. Spores require moisture to activate their metabolic processes, but excessive water can lead to contamination or spore damage. Mist the substrate lightly to maintain surface moisture without saturating it, aiming for a humidity level of 70–80%. Alternatively, use a humidification chamber with a water source to create a consistent environment. For advanced growers, a sterile water spray with a fine mist nozzle ensures even distribution without disturbing the spores. This step is crucial because improperly hydrated spores may fail to germinate or become vulnerable to mold, delaying the transition to the monotub phase.

Nutrient availability plays a subtle yet significant role in spore germination, even though spores themselves do not consume nutrients directly. The substrate should contain a balanced mix of carbohydrates, proteins, and micronutrients to signal a fertile environment. Common choices include vermiculite, brown rice flour, or manure-based mixes, which provide both structure and nourishment. Avoid over-enriching the substrate, as excess nutrients can attract contaminants. A simple, proven recipe is a 50/50 blend of vermiculite and organic brown rice flour, lightly moistened and sterilized before inoculation. This minimal yet effective approach ensures spores detect a hospitable environment, encouraging swift germination without unnecessary complexity.

Finally, patience and observation are as vital as any environmental factor. While optimal conditions can shorten germination time to 24–48 hours, variability is normal. Monitor the substrate for signs of activity, such as slight discoloration or visible hyphae, but avoid disturbing the setup unnecessarily. If germination stalls beyond 72 hours, reassess temperature, humidity, and sterility. For growers tracking progress, documenting conditions and outcomes can reveal patterns and refine future attempts. By treating germination as a scientific process rather than a waiting game, cultivators can consistently achieve the rapid spore-to-monotub timeline essential for efficient mushroom production.

Crafting Spore Blossoms: Possibilities, Methods, and Creative Applications Explored

You may want to see also

Timeframe for Mycelium Colonization

The journey from spore to monotub is a fascinating process, but it's the mycelium colonization stage that often sparks the most curiosity and concern among cultivators. This phase is crucial, as it sets the foundation for a successful harvest. So, how long does it take for mycelium to colonize, and what factors influence this timeframe?

Understanding the Variables: Mycelium colonization time can vary significantly, typically ranging from 7 to 21 days, but it's not uncommon for it to take up to 4 weeks or more in certain conditions. The primary factors at play here are the mushroom species, environmental conditions, and the quality of your substrate. For instance, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are known for their rapid colonization, often taking just 7-14 days, while some gourmet varieties like shiitake (Lentinula edodes) may require 3-4 weeks. Temperature is a critical variable; most species thrive in a range of 70-75°F (21-24°C), with deviations potentially slowing down or inhibiting growth. Humidity levels, airflow, and the initial spore or spawn quality also play pivotal roles.

Optimizing Conditions for Speed: To expedite colonization, consider these practical steps. First, ensure your substrate is fully sterilized to eliminate competitors. Maintain a consistent temperature within the optimal range, using heating pads or insulation if necessary. Proper hydration is key; aim for a moisture content of around 60-70% in your substrate. Adequate airflow is often overlooked but crucial—stagnant air can lead to contamination. Regularly monitor your setup, especially during the initial stages, to catch any issues early. For those seeking a head start, using grain spawn instead of spores can reduce colonization time by several days, as the mycelium has already established a strong network.

The Waiting Game and Potential Pitfalls: Patience is a virtue in mycology. While it's tempting to intervene, avoid the urge to constantly check on your monotub, as this can introduce contaminants. Instead, focus on creating the ideal environment and let nature take its course. Common mistakes include over-watering, which can lead to soggy conditions and mold, and insufficient sterilization, leaving your substrate vulnerable to bacteria and other fungi. Remember, each species has its own timeline, and rushing the process can compromise the entire batch.

In the world of mushroom cultivation, understanding and respecting the mycelium's colonization process is paramount. By providing the right conditions and allowing sufficient time, cultivators can ensure a healthy, robust mycelium network, setting the stage for a bountiful harvest. This phase is a testament to the delicate balance between human intervention and the natural growth processes of these fascinating organisms.

Analyzing Pollen and Spore Samples: Techniques and Insights Revealed

You may want to see also

Transferring Colonized Substrate to Monotub

The journey from spore to monotub is a delicate dance, and transferring colonized substrate marks a critical transition. This step demands precision and care to ensure the mycelium’s health and future fruiting potential. Timing is paramount—transfer too early, and the substrate may not be fully colonized; too late, and contamination risks rise. Typically, substrate is ready for transfer 7 to 14 days after inoculation, depending on factors like temperature, humidity, and substrate composition. Observing full colonization—white, healthy mycelium throughout the substrate—is your cue to proceed.

Analyzing the process reveals a balance between patience and action. The substrate should be colonized enough to outcompete contaminants but not so mature that it begins fruiting prematurely. A common mistake is rushing the transfer, leading to underdeveloped mycelium that struggles in the monotub environment. Conversely, waiting too long can deplete nutrients or invite mold. Ideal conditions for colonization include a temperature range of 75–80°F (24–27°C) and high humidity, often achieved in a sealed container like a shoebox or tub. Monitoring these factors ensures the substrate is ready for its next stage.

Instructively, the transfer process begins with preparing the monotub. Sterilize the tub and ensure proper ventilation by drilling ¼-inch holes along the sides and lid, covered with micropore tape to allow gas exchange while blocking contaminants. Gently break up the colonized substrate to expose more mycelium, but avoid damaging it. Layer the substrate evenly in the monotub, maintaining a depth of 1–2 inches to promote even growth. Mist the substrate lightly with distilled water to rehydrate it, but avoid over-saturating, as excess moisture can lead to anaerobic conditions.

Comparatively, this step differs from earlier stages, like inoculation, where precision is less critical. Here, every action impacts the mycelium’s ability to thrive. For instance, while inoculation involves distributing spores evenly, transferring substrate requires careful handling to preserve the mycelial network. Unlike bulk substrate preparation, where mixing is thorough, this transfer focuses on minimal disturbance. The goal is to create an environment where the mycelium can expand rapidly, setting the stage for fruiting.

Descriptively, a successful transfer is marked by the monotub’s transformation into a bustling hub of mycelial activity. Within days, the substrate should show signs of renewed growth, with mycelium spreading across the surface and sides. Properly executed, this step bridges the gap between colonization and fruiting, turning a small, contained substrate into a thriving ecosystem. Patience, observation, and attention to detail are your greatest tools, ensuring the transition is seamless and productive.

Microsporidia Sporulation: Fruiting Body Involvement Explained in Detail

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Factors Affecting Growth Speed

The journey from spore to monotub is a delicate dance of biology and environmental control, with growth speed hinging on a multitude of factors. Understanding these variables empowers cultivators to optimize their process, potentially shaving weeks off the timeline.

Let's delve into the key players influencing this critical phase.

Environmental Symphony: The Non-Negotiable Trio

Temperature, humidity, and light form the holy trinity of mushroom cultivation. Ideal fruiting temperatures for most gourmet mushroom species fall between 65-75°F (18-24°C). Deviations outside this range can significantly slow growth or even halt it entirely. Humidity, the silent partner, should be maintained around 80-90% within the monotub. This mimics the damp, forest floor conditions mushrooms crave. While mushrooms don't require intense light for photosynthesis, indirect, natural light or a few hours of fluorescent light daily encourages healthy pinhead formation and fruiting body development.

Pro Tip: Invest in a reliable thermometer/hygrometer to monitor these crucial parameters.

Substrate: The Nutritional Foundation

The substrate, essentially the mushroom's food source, plays a pivotal role in growth speed. Different mushroom species have specific substrate preferences. For example, oyster mushrooms thrive on straw, while shiitakes prefer hardwood sawdust. The quality and sterilization of the substrate are equally important. Contaminants can compete with the mycelium for resources, stunting growth. Proper sterilization techniques, such as pressure cooking or pasteurization, are essential to eliminate unwanted organisms.

Strain Selection: The Genetic Blueprint

Not all mushroom strains are created equal. Some strains are naturally faster colonizers and fruiters than others. Researching and selecting a strain known for its vigor can significantly reduce the time from spore to harvest. Reputable spore vendors often provide information on strain characteristics, including growth speed.

Techniques for Acceleration

Beyond the fundamentals, cultivators can employ techniques to expedite the process. Grain spawn, a nutrient-rich medium inoculated with mycelium, can be used to introduce a robust mycelial network into the substrate, jumpstarting colonization. Additionally, maintaining optimal airflow within the monotub prevents the buildup of carbon dioxide, which can inhibit growth. Caution: Avoid excessive airflow, as it can lead to drying.

Advanced Technique: Experienced growers may experiment with "field capacity" – the optimal moisture level for the substrate – to further fine-tune growth conditions.

Do Spores Have a Nucleus? Unveiling the Microscopic Truth

You may want to see also

Signs of Readiness for Monotub Fruiting

The transition from spore to monotub is a delicate dance, and knowing when your mycelium is ready for fruiting is crucial for a successful harvest. One of the earliest signs of readiness is the colonization of the substrate. When the mycelium has fully colonized the bulk substrate, typically within 7-14 days, it forms a dense, white network throughout the material. This is a visual cue that the mycelium has established itself and is ready for the next phase. However, it's essential not to rush this process; premature introduction to the monotub can lead to contamination or poor fruiting.

As the mycelium matures, it begins to signal its readiness for fruiting through the formation of primordial structures, often referred to as "pins." These tiny, pinhead-like formations are the earliest stage of mushroom development and usually appear 5-10 days after the mycelium has fully colonized the substrate. The presence of pins is a clear indication that the mycelium is redirecting its energy towards fruiting. At this stage, maintaining optimal conditions—such as humidity levels between 90-95% and a temperature range of 70-75°F—is critical to encourage pin growth and prevent aborts.

Another key indicator of readiness is the mycelium's response to environmental cues. When the mycelium is mature, it becomes more sensitive to changes in light, humidity, and fresh air exchange. Introducing a 12-hour light cycle, preferably with indirect natural light or a low-intensity grow light, can stimulate pin formation. Additionally, increasing fresh air exchange by opening the monotub slightly (about 1-2 inches) helps prevent CO2 buildup, which can inhibit fruiting. These adjustments should be made gradually to avoid shocking the mycelium.

For those using a monotub setup, the substrate's moisture content is a critical factor in determining readiness. The substrate should be moist but not waterlogged, with a field capacity of around 60-70%. Overly wet conditions can lead to anaerobic environments, fostering contamination, while too dry a substrate can hinder pin initiation. Regularly misting the substrate and ensuring proper drainage are essential practices. A simple test is to squeeze a handful of substrate; it should hold together but release a few drops of water.

Finally, the age of the mycelium plays a significant role in its readiness for fruiting. While colonization times vary, most substrates are ready for fruiting conditions within 2-3 weeks of inoculation. However, this timeline can extend depending on factors like temperature, humidity, and substrate composition. Patience is key; allowing the mycelium to fully mature ensures a stronger, more resilient network capable of producing multiple flushes. Monitoring these signs—colonization, pin formation, environmental responsiveness, substrate moisture, and age—provides a comprehensive guide to determining the optimal time to initiate fruiting in your monotub.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Pink Eye? Uncovering the Surprising Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The time from spore to monotub typically ranges from 6 to 8 weeks, depending on factors like mushroom species, environmental conditions, and cultivation techniques.

The stages include spore germination (1-2 weeks), mycelium colonization (2-4 weeks), and fruiting conditions setup (1-2 weeks). Total time varies based on species and care.

Yes, using techniques like multi-spore syringes, optimal temperature (22-26°C), and proper humidity can reduce the time. However, rushing the process may compromise yield or quality.